Introduction

Spasticity is an upper motor neuron disorder commonly seen in people with neurological conditions such as stroke, cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, and multiple sclerosis. Reference Pandyan, Gregoric and Barnes1,Reference Barnes, Kocer, Murie Fernandez, Balcaitiene and Fheodoroff2 Spasticity can impair physical function and negatively impact the daily lives of individuals and their caregivers. Reference Barnes, Kocer, Murie Fernandez, Balcaitiene and Fheodoroff2 It is important to treat spasticity to improve or maintain a person’s quality of life.

Spasticity management typically requires a multi-modal treatment approach, which can include interventions such as exercise (e.g., stretching), functional electrical stimulation, task-oriented activities, serial casting, bracing, intrathecal baclofen, oral antispasticity medications, chemodenervation, and surgery. Reference Pilitsis and Khazen3 As spasticity can be a consequence of different central neurologic conditions and can affect people in different ways, it is essential that treatment plans and goal setting be individualized to each person’s needs. Reference Francisco, Balbert and Bavikatte4 Expert consensus recommendations highlight the need for coordinated multidisciplinary team management of spasticity. Reference Bavikatte, Subramanian, Ashford, Allison and Hicklin5 A lack of interdisciplinary effort can be a barrier to best practices, in addition to fiscal and organizational challenges. Reference Lanig, New and Burns6 A comprehensive physical and functional examination is crucial to assess spasticity and help set patient-specific targeted treatment goals. Physical examinations undertaken by clinicians include visual observation of the individual’s movement, posture, and assessment of muscle strength, tone, and reflexes. Reference Balakrishnan and Ward7,Reference Hugos and Cameron8 Pain should also be evaluated. Spasticity scales such as the Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS), Tardieu Scale (TS), Modified Tardieu Scale (MTS), Resistance to Passive Movement Scale (REPAS), and Spasm Frequency Scale (SFS) are tools that are used to assess spasticity and monitor the outcomes of treatment. Reference Mostoufi9–Reference Haugh, Pandyan and Johnson11 However, it is not clear if the physical evaluations and assessment tools for spasticity management are used by clinicians in a consistent and routine or standardized way. Reference Skalsky12

Clinicians treating individuals with spasticity want to know what spasticity assessments should be performed routinely and if different methods of assessment vary by spasticity etiology. Understanding the current practice of spasticity assessment will help provide guidance for clinical evaluation and management of spasticity. While interdisciplinary team management of spasticity is recommended, Reference Bavikatte, Subramanian, Ashford, Allison and Hicklin5,Reference Lanig, New and Burns6 real-world utilization of this approach is unknown. A survey of Canadian physicians has been used to assess the commonality of spasticity-related treatment in patients undergoing surgery. Reference Kassam, Saeidiborojeni, Finlayson, Winston and Reebye13 Using similar survey methods, this study aimed to determine the composition of the spasticity management team and the physical evaluations and assessment tools used by a group of Canadian healthcare professionals treating adults with spasticity.

Methods

Study design

This study was a cross-sectional national survey. A web-based survey was distributed to healthcare professionals across Canada treating individuals with spasticity. The survey was structured to determine the different types of physical evaluations, tone-related impairment measurements, and assessment tools being used in the management of adults with spasticity. The University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board approved this study (number H20-02118).

Participants

Healthcare professionals included in the study were identified from the Canadian Advances in Neuro-Orthopedics for Spasticity Congress (CANOSC) database, a nonprofit educational organization. CANOSC members are predominantly physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians, but also include specialists in plastic surgery, neurology, pediatrics, orthotics, nursing, orthopedics, as well as a small percentage of medical students, industry colleagues, and non-practicing physicians. While the CANOSC database is not representative of all clinicians managing spasticity in clinical practice, it does provide a convenience sample of individuals with a particular interest in spasticity management. An electronic or paper letter of initial contact was sent on January 20, 2021, to the CANOSC data base healthcare professionals through the member mailing list, which included a description of the research study and a link to the survey. Reminders were sent out on February 4, March 4, and March 9, 2021. In all, the survey was distributed to 742 contacts on the CANOSC mailing list.

Survey

The web-based survey comprised 19 questions (consisting of multiple-choice, multiple-answer, and open questions) and was developed by the authors through a consensus process (Supplementary file 1). The survey was developed and reviewed via email. Authors participated in two rounds of review and had the additional opportunity to provide feedback during final approval of the survey. All authors provided final approval prior to the distribution of the survey. Survey questions 1–8 asked respondents about their work setting, clinical experience, and routine practice in relation to spasticity care. Questions 9–19 queried respondents about spasticity management teams, physical evaluations, and assessment tools used at initial and subsequent visits. A free-text box for any additional comments was provided at the end of the survey.

Data collection and analysis

The survey was hosted electronically from January 20 to March 16, 2021, with the server located in Canada and complying with relevant privacy legislation. Completed surveys and responses to open questions were analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics. Percentage of affirmative responses was calculated based on the number of responders who completed the survey.

Results

Participants

Of the 742 contacts on the CANOSC mailing list, 80 respondents completed the survey and are included in the analysis. This resulted in a response rate of 10.8% although the database of CANOSC members was large and may not represent an accurate denominator of all clinicians managing spasticity. While most participants were physiatrists (n = 61) other specialists or healthcare providers’ opinions can also be valuable. The non-physiatrist healthcare professionals (n = 19) included 10 physiotherapists, 3 occupational therapists, 2 nurses, 1 neurologist, 1 family medicine specialist, and 1 ‘other’. The respondents comprise healthcare professionals in relevant spasticity specialties treating a wide range of spasticity etiologies (Table 1). All study participants were from Canada, including Ontario (27.5%, 22/80), British Columbia (20.0%, 16/80), Alberta (15.0%, 12/80), Quebec (10.0%, 8/80), Saskatchewan (5.0%, 4/80), New Brunswick (5.0%, 4/80), Prince Edward (2.5%, 2/80), and Nova Scotia (1.3%, 1/80); 8.8% (7/80) selected ‘other’ and 5.0% (4/80) did not provide a response.

Table 1: Respondents’ work setting, clinical experience, and routine practice in relation to spasticity care

a Respondents were asked to select all that apply; therefore, percentages do not total 100%. OT, occupational therapist; PT, physiotherapist.

Participants’ practice setting, clinical experience, and routine practice in relation to spasticity care are shown in Table 1. The most common practice settings were academic hospitals/medical centers (62.5%, 50/80 participants), community/private practices (35.0%, 28/80), spasticity clinics (27.5%, 22/80), and/or nonacademic hospitals/medical centers (25.0%, 20/80) (respondents were asked to select all settings that apply). Participants had worked with individuals with spasticity for a median of 10.5 years (interquartile range: 5–19.5 years).

Most participants (90.0%, 72/80) reported seeing either ‘primarily adults’ or ‘mostly adults with some pediatric cases’ in their spasticity practice. The majority of the respondents (60.0%, 48/80) see at least 10 individuals with spasticity in need of treatment each month. Etiologies of spasticity among individuals seen by study participants included stroke, traumatic brain injury, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, motor neuron disease, and hereditary spastic paraparesis (Table 1).

When participants were asked about the preferred definition of ‘spasticity’ used in their practice, the most frequent response (72.5%, 58/80) was the Lance (1980) definition: a ‘motor disorder characterized by a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes (muscle tone) with exaggerated tendon jerks, resulting from hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex, as one component of the upper motor neuron syndrome’. Reference Lance14 Participants were able to select all applicable definitions. The second most frequent response (51.3%, 41/80) was the Pandyan et al. (2005) definition: a ‘disordered sensorimotor control, resulting from an upper motor neuron lesion, presenting as an intermittent or sustained involuntary activation of muscles’. Reference Pandyan, Gregoric and Barnes1

Spasticity assessments

Healthcare team

When asked about who is involved in spasticity assessment, 57.5% (46/80) of the total participants chose responses that were a combination of a physiatrist and another specialist (e.g., nurse, physiotherapist, and/or occupational therapist) as needed (Table 1). However, 27.5% (22/80) of participants reported a physiatrist being the only clinician involved.

Approximately half (46.3%, 37/80) of the participants reported having an inter- or trans-disciplinary team (several medical specialties, each focused on a specific individual’s condition, treatment goals, and methods for improving outcomes) available to manage individuals with spasticity (46.3%, 37/80 responded ‘no’; 7.5%, 6/80 did not respond). Interdisciplinary spasticity management teams most often included occupational therapists, physical therapists, and nurses (Figure 1A). Independent of their response to the inter-disciplinary team query, participants were also asked whom they wished to have as part of their team and could select all applicable specialists. Out of the 66 study participants who answered this question, the most frequent responses were a physical therapist (51.5%, 34/66) and an orthotist (43.9%, 29/66), followed by an occupational therapist (37.9%, 25/66) (Figure 1B). Only 6.1% (4/66) indicated that they did not wish for additional team members; these respondents were practicing in an academic hospital or medical center and already had an inter- or trans-disciplinary team consisting of a nurse, occupational therapist, and a physical therapist. Of the participants who did not have an inter- or trans-disciplinary team (n = 37), 73.0% (27/37) wished for a physical therapist, 56.8% (21/37) wished for an occupational therapist, 56.8% (21/37) wished for an orthotist, and 51.4% (19/37) wished for a nurse.

Figure 1: Interdisciplinary teams: (A) current team members, and (B) desired team members.

Physical evaluations & assessment tools

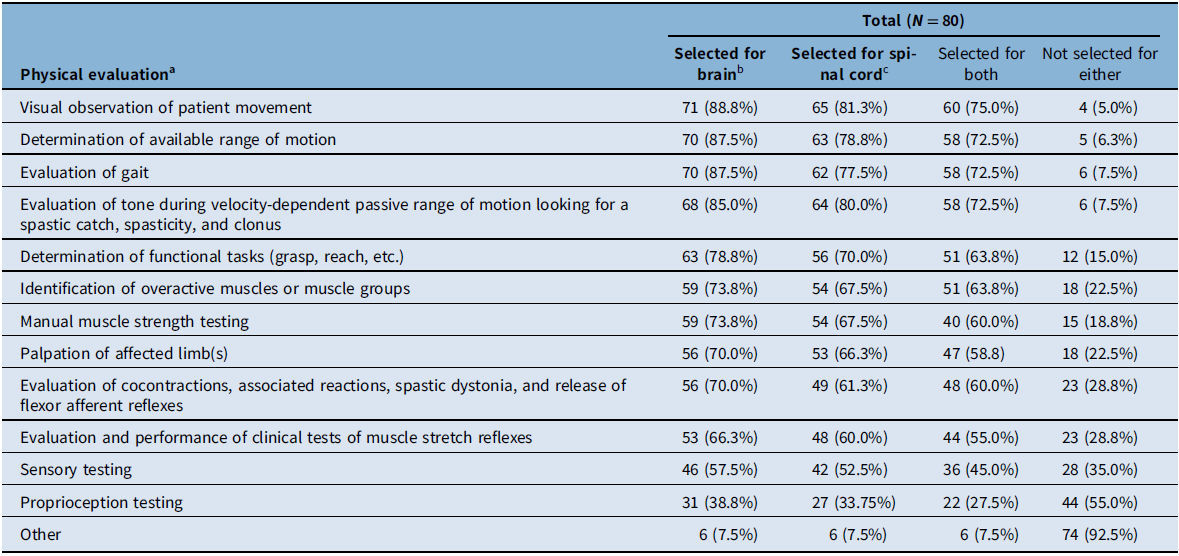

Study participants were provided with a list of 12 types of physical evaluations and were asked to select all that applied as part of the initial physical evaluation of individuals with each type of spasticity etiology: brain-predominant (pre-defined in the survey as stroke, traumatic brain injury, and cerebral palsy) or spinal cord–predominant (pre-defined as multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, motor neuron disease, and hereditary spastic paraparesis) (Table 2). In the total population (N = 80), the physical evaluations most frequently used in initial evaluations were visual observation of movement (selected by 81.3%–88.8% of participants for spinal cord–predominant or brain-predominant etiologies, respectively); determination of available range of motion (78.8%–87.5%); tone during velocity-dependent passive range of motion looking for a spastic catch, spasticity, and clonus (80.0%–85.0%); and evaluation of gait (77.5%–87.5%) (Table 2). The least selected physical evaluation, regardless of the etiology, was proprioception testing. When comparing brain-predominant etiologies versus spinal cord-predominant etiologies, each of the 12 physical evaluation types were used at similar rates; however, evaluation use was slightly higher in brain-predominant etiologies for all types (Table 2). When comparing evaluation use by physiatrists versus other healthcare professionals, the four most commonly used evaluations were the same in the physiatrist group as the total participants; other healthcare professionals more commonly used ‘determination of functional tasks’ (63.2%–68.4%) over ‘velocity-dependent passive range of motion tone evaluation’ (57.9% for both etiologies). A greater percentage of physiatrists reported using each type of evaluation compared to other healthcare providers. Overall, regardless of the etiology, 73.8% (59/80) of study participants indicated that their physical evaluation of individuals with spasticity differs in subsequent visits. Compared to the initial evaluations, subsequent assessments were described as being more focused on the individual’s goals or areas of concern and the effects of treatment.

Table 2: Physical evaluations used in the initial examination of patients with spasticity

a Respondents were asked to select all that apply for each etiology type. Percentages were calculated for each evaluation type in each of the evaluated populations (i.e., total respondents, physiatrists, and other healthcare professionals).

b Brain-predominant etiologies were defined as stroke, traumatic brain injury, and cerebral palsy.

c Spinal cord–predominant etiologies were defined as multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, motor neuron disease, and hereditary spastic paraparesis.

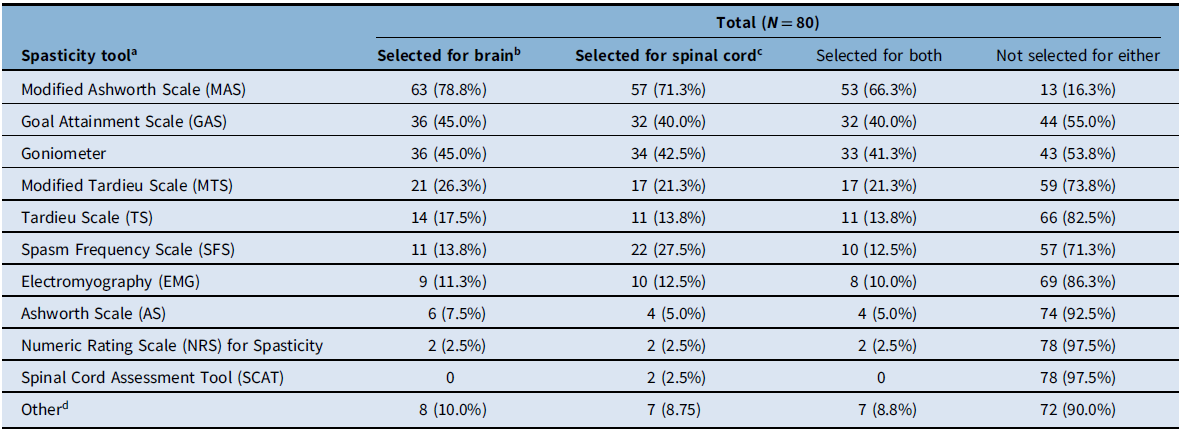

Participants were then asked to specify which spasticity assessment tools they use by selecting all choices that applied for each type of spasticity etiology (brain-predominant vs spinal cord–predominant). In the total population (N = 80), the most frequently used spasticity tools were MAS (selected by 71.3%–78.8% of participants for spinal cord–predominant or brain-predominant etiologies, respectively), goniometer (42.5%–45.0%), and Goal Attainment Scale (GAS; 40.0%–45.0%) (Table 3). The least selected tools were the Spinal Cord Assessment Tool and Numeric Rating Scale for Spasticity. When comparing brain-predominant etiologies versus spinal cord-predominant etiologies, similar rates were observed with the greatest difference seen with the SFS, which was used more for spinal cord-predominant etiologies (27.5%) compared to brain predominant (13.8%) (Table 3). When comparing spasticity tools used by physiatrists versus other healthcare professionals, MAS, GAS, and goniometer were most frequently selected by both groups, with physiatrists being more likely to select each tool compared to other healthcare professionals. For example, in brain-predominant etiologies most physiatrists (86.9%) used MAS, while only half (52.6%) of other healthcare professionals selected this tool. Physiatrists were more likely to use each of the tools in the survey, with the exception of the Numeric Rating Scale for Spasticity (no physiatrists selected this tool, while 2/19 other healthcare professionals did). Overall, regardless of the etiologies, 82.5% (66/80) of study participants indicated that the spasticity scales they use at the initial visit are the same for subsequent visits. Participants were also asked about which top three spasticity scales they use for assessment of each etiology (stroke, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, etc.). For all etiologies, the top three scales that study participants used most frequently included MAS, GAS, and goniometer.

Table 3: Tools used for evaluation of patients with spasticity

a Respondents were asked to select all that apply for each etiology type. Percentages were calculated for each scale for each of the evaluated populations (i.e., total respondents, physiatrists, and other healthcare professionals).

b Brain-predominant etiologies were defined as stroke, traumatic brain injury, and cerebral palsy.

c Spinal cord–predominant etiologies were defined as multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, motor neuron disease, and hereditary spastic paraparesis.

d Responses included clinical description of function, video and photographic capture of pre- and post-injection/intervention, gait evaluation, qualitative description, and spasm severity.

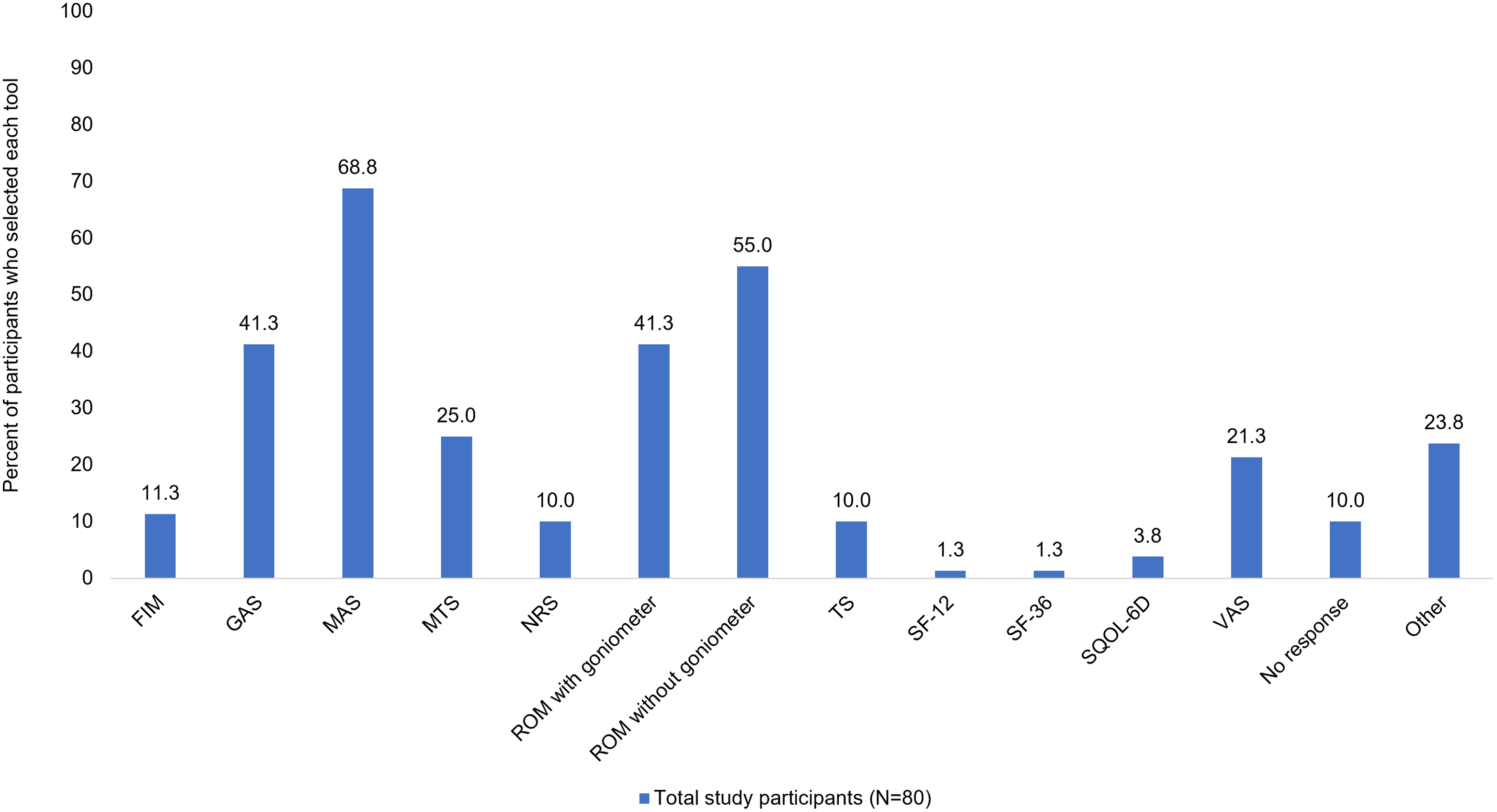

When participants were asked what tools they use to measure an individual’s quality of life when doing routine clinical spasticity assessments, the most common response was that they do not evaluate quality of life (32.5%, 26/80) followed by the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; 27.5%, 22/80), and Functional Independence Measure (FIM; 15.0%, 12/80). Although FIM does not directly measure quality of life, it was included as a survey option since measurements of self-care independence are assumed to correlate with quality of life. Participants were also asked what tools they routinely use to assess each individual’s response to treatment. The most common responses were the MAS (68.8%, 55/80), range of motion assessment without goniometer (55.0%, 44/80), range of motion assessment with goniometer (41.3%, 33/80), and GAS (41.3%, 33/80) (Figure 2). When participants were asked how goals are evaluated in their clinical practice, the most common response was that they used a qualitative description of goal outcome (37.5%, 30/80) (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Tools routinely used to assess each patient’s individual response to treatment. Respondents were asked to select all that apply. The following scales were not selected by any respondents: Ashworth Scale (AS), EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D), Spinal Cord Injury Spasticity Evaluation Tool (SCI-SET), World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF). FIM, Functional Independence Measure; GAS, Goal Attainment Scale; MAS, Modified Ashworth Scale; MTS, Modified Tardieu Scale; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; ROM, range of motion; SF-12, 12-Item Short Form Survey; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Survey; SQoL-6D, Spasticity-Related Quality of Life 6-Dimensions Questionnaire; TS, Tardieu Scale; VAS, Visual Analog Scale.

Figure 3: Most frequently used tool for evaluating goals in clinical practice. Respondents were asked to select the most frequently used evaluation tool. MAS, Modified Ashworth Scale; ROM, range of motion.

Discussion

The current study used a web-based survey to determine the physical evaluations and assessment tools used by a subgroup of Canadian clinicians (physiatrists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals) treating adults with spasticity. To our knowledge, this is the first cross-sectional national survey assessing clinicians’ practice patterns regarding the use of physical evaluations and assessment spasticity tools for spasticity management.

Survey participants gravitated toward describing ‘spasticity’ based on the classic description by Lance (1980), which was first published more than four decades ago. Reference Lance14 The definition of spasticity has since evolved. Less prominence was given by the participants to the wider definition of disordered sensory-motor control by Pandyan (2005). Reference Pandyan, Gregoric and Barnes1 The refinement of the spasticity definition is ongoing; a recently proposed definition by Li (2021) incorporates the essential element of ‘velocity-dependent increase in tone’ from Lance’s definition and adds the inherent pathophysiology underlying spasticity and the coexistence of other related motor impairments that share similar pathophysiological origins. Reference Li, Francisco and Rymer15 Spasticity-causing neurological disorders are heterogeneous in terms of underlying phenotype. Healthcare professionals treating individuals with spasticity treat various manifestations of muscle overactivity from central nervous system injury not limited to the velocity-dependent increase in stretch reflexes. This new definition is helpful because it conceptualizes spasticity assessment and management within the goal of neural recovery. Reference Li, Francisco and Rymer15

The spasticity teams’ structure may be dependent on healthcare system architecture and resources in each province or health authority. Our study results also revealed that management of spasticity is frequently performed in the academic hospital setting as well as in the community; however, the predominance of individuals practicing in the academic or medical center setting may be reflective of the CANOSC database, which may over-represent this population. Opportunities likely exist to deliver similar inter-disciplinary spasticity care models in community practice as those in the more traditional hospital-based spasticity clinics, although region-specific organizational, fiscal, and health system-based barriers may need to be overcome. Reference Lanig, New and Burns6 Our study revealed that the majority of clinicians would value having more interdisciplinary collaboration with other healthcare providers when managing individuals with spasticity. Interdisciplinary teams can contribute to the clinical improvement of individuals with spasticity Reference Wissel, Ward and Erztgaard16,Reference Demetrios, Khan, Turner-Stokes, Brand and Mcsweeney17 and are imperative when spasticity management is viewed under the umbrella of supporting neural recovery. The expert roles of allied healthcare professionals (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, registered nurses, orthotists, kinesiologists, etc.) complement assessment and management of individuals with spasticity. It is encouraging that in Canada 66.3% of clinicians report more than one team member being involved in spasticity assessments. It is essential when managing spasticity to consider an interdisciplinary team approach especially in patients with medium-to-high risk of developing post-stroke spasticity, where specialist intervention may be key to proper assessment and therapeutic success. Reference Bavikatte, Subramanian, Ashford, Allison and Hicklin5

Clinicians indicated a varied range of physical examinations to evaluate spasticity. While our findings show some consistency in the evaluations used by a majority of clinicians across etiologies, minor differences still exist. Physiatrists were more likely to use physical evaluations compared to other healthcare professionals. Respondents also indicated a wide range of assessment tools to evaluate spasticity, with physiatrists again more likely to use these tools (with the exception of Numeric Rating Scale for Spasticity) compared to other types of specialists.

The most frequently used spasticity assessment tools for acquired brain injury/cerebral palsy and spinal cord practice settings included the MAS, goniometer, and the GAS. The MAS is used to ascertain the presence and physiological severity of spasticity. Reference Harb and Kishner18 It is a well-established and widely used tool in the clinical assessment of extremity spasticity. Reference Harb and Kishner18 The MAS is also amongst the most commonly used tools to evaluate the effects of interventions for the treatment and management of spasticity. Reference Harb and Kishner18 It is easy to use, quick to perform in the clinic, and does not require any special instrumentation. Reference Harb and Kishner18 There are issues with inter- and intra-rater reliability, Reference Harb and Kishner18 but it is one of the only clinically feasible tools available to clinicians. Meanwhile, the GAS is an established, patient-centered tool that is predominantly used to assess the effects of spasticity on one’s body/life experience and set goals related to these problems so as to assess response to treatments targeted at decreasing spasticity. Reference Turner-Stokes19 Unlike the MAS and MTS, which provide some measure of the excessive tone, the GAS is not a scale to assess the severity of spasticity; however, it represents a unique approach to identifying and quantifying individualized, meaningful treatment outcomes. Reference Ertzgaard, Ward, Wissel and Borg20 In our study, GAS was utilized by less than half of the survey respondents, which may be due to several limitations. For example, individuals with severe cognitive impairment may be unable to set goals for themselves or, due to their disability, may be unable to recognize their achievements. Reference Ertzgaard, Ward, Wissel and Borg20 Training in goal setting and scaling procedures is needed prior to GAS use in clinical practice. Reference Ertzgaard, Ward, Wissel and Borg20 Goal setting is an interactive process to develop practical individual goals. The utility of GAS is higher when the goals are developed in an interdisciplinary team setting and allow for treatment plans tailored towards a coordinated goal set. Reference Stolee, Zaza, Pedlar and Myers21 This might explain why the GAS was not used by all survey participants; when used by a single clinician, in the absence of a team effort, GAS may be perceived as burdensome and time-consuming. Reference Stolee, Zaza, Pedlar and Myers21

Evaluation and regular monitoring of spasticity are important for formulating the treatment plan, assessing response to treatment, and modifying the treatment plan if needed. The MAS and VAS are both good tools to assess an individual’s response to treatment because they measure the clinician perception and patient perception, respectively, so they are complementary. However, the use of the GAS in everyday clinical care helps ensure that the treatment of spasticity is not only goal-focused, but also individualized, in order to maximize its benefits. Qualitative description of goal outcomes and documentation of goals attained is also encouraged. The Canadian clinicians participating in the current survey also indicated routinely using range of motion assessment with or without goniometer to assess an individual’s response to treatment. A standardized approach to assessing spasticity and evaluating treatment outcomes over time could improve care and facilitate the conduction of future collaborative research.

Greater uptake of quality of life assessments would be beneficial. This is especially important after treatment when the individuals are seen for follow-ups. Quality of life scales that are easy to use and that can even be used by individuals at home include the VAS to rate current status of health and the 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) to assess the impact of spasticity on their everyday life. The European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire is quick to administer and widely used, including in spasticity. Reference Fheodoroff, Rekand and Medeiros22 The SQoL-6D is a newly developed questionnaire specific to upper-limb spasticity. Reference Turner-Stokes, Fheodoroff and Jacinto23

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. Survey results are susceptible to voluntary response bias. The small sample size of this study likely reflects the Canadian landscape of healthcare professionals involved in the treatment of spasticity in an academic or community-based clinic setting based on the CANOSC membership, which is closely aligned with the Canadian Association of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation (CAPMR). Further, survey participants were predominantly physiatrists, and their responses may not fully represent the breadth of clinicians involved in the treatment of spasticity (e.g., noteworthy is the scarcity of neurologists). Although the survey response rate was low (10.8%), it is important to note that the denominator is the database of CANOSC members (N = 742), which includes individuals with unknown backgrounds, nonclinical specialties (e.g., industry professionals, medical students, and nonpracticing physicians), and international members. Background information is reported for survey participants, but was not available for all CANOSC members. While the CANOSC database may include industry colleagues and non-practicing physicians who may pose a conflict of interest in terms of responses, our study specifically focused on Canadian physicians and allied health care clinicians involved directly in the treatment of adults with spasticity, which represents a smaller subset of the CANOSC members. A recent 2021 cross-sectional study (Kassam, et al.) also surveyed Canadian physicians treating spasticity using the CANOSC database that we used for our study. Reference Kassam, Saeidiborojeni, Finlayson, Winston and Reebye13 In Kassam’s study, 138 Canadian physicians from CANOSC were identified as being directly involved in the treatment of patients with spasticity and 34 (25%) completed their study. Reference Kassam, Saeidiborojeni, Finlayson, Winston and Reebye13 In our study, 62 Canadian physicians completed the survey, which represents 45% of the Canadian CANOSC physician members based on Kassam’s study. Surveys with relatively low response rates can still be of good quality and validity if the population being surveyed is fairly homogeneous in terms of training and employment, Reference Taylor and Scott24 such as is the case in the current study. In our survey, not all survey questions were answered by all participants. The survey did not distinguish between hospital- versus community-based spasticity clinics. The survey also did not assess how pain is assessed and managed in patients with spasticity. Finally, the survey was designed by physicians; input from other specialties (e.g., physiotherapists and occupational therapists) would have been valuable to prevent bias toward physicians.

Our survey was disseminated to members of CANOSC, resulting in a sample of 80 fully completed surveys by clinicians directly involved in the treatment of spasticity. This subgroup could be approached for future survey studies to better analyze the differences in Canadian practice patterns regarding spasticity assessment of individual professions to better assess the barriers to the use of certain spasticity assessment tools. This survey has identified the need to conduct further research to develop guidance and guidelines in use of spasticity assessment tools and can help in the development of robust questions when developing a Delphi process for the use of spasticity assessment tools in the real-world clinical setting. Results from this study are specific to Canadian clinicians and we acknowledge spasticity management patterns in the rest of world may vary.

Conclusion

Our survey provided valuable insight into the ideal spasticity management team members and the physical evaluations and assessment tools used by healthcare professionals in clinical practice. Although a wide range of validated outcome measures are available, only a few of those truly capture the key effects of intervention at the individual patient levels. Our findings emphasize the preference of practicing clinicians for interdisciplinary spasticity management teams. Clinicians utilize several physical evaluation and assessment tools for managing spasticity of brain or spinal cord etiology, including measurement of tone-related impairment (e.g., MAS, MTS, VAS) as well as individualized goal-oriented assessments (GAS) and quality of life scales in order to guide treatment and assess outcomes.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2022.326.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance and editorial support were provided by Kate Katsaval, BSc, and Julie O’Grady, BA, of The Medicine Group, LLC (New Hope, PA, USA) in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines. Survey development, data analysis, medical writing, and editorial support were paid for using a grant (no. 2019-47) from Ipsen Canada (Mississauga, Ontario). Ipsen’s contribution to this manuscript was limited to funding; they did not contribute to survey development, statistical analysis, or manuscript writing.

Statement of Authorship

PBM, CB, SPD, FI, SMM, TAM, CMO, RNR, LES, THW, and PJW made significant contributions to the methodology and survey development. All authors reviewed the analysis and interpreted the results, contributed to the original draft preparation, and made significant revisions to preliminary drafts. All authors approved the final version.

Funding

Survey development, data analysis, medical writing, and editorial support were paid for using a grant (no. 2019–47) from Ipsen Canada (Mississauga, Ontario).

Disclosures

Patricia B. Mills has received a grant or contract from Ipsen Canada, Allergan/AbbVie, and Merz. Chetan P. Phadke has nothing to declare. Chris Boulias has received grants from Allergan/AbbVie, Ipsen, and Merz; has received consulting fees, honoraria, and travel support from Allergan/AbbVie and Merz; is a member of the advisory boards of Allergan/AbbVie, Ipsen, and Merz; and has received honoraria for presentations from Allergan/AbbVie and Merz. Sean P. Dukelow has received operating grants from Brain Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Heart and Stroke Foundation; received consulting fees from Prometheus Medical Consulting and Sinntaxis; received honoraria from Allergan/AbbVie, Ipsen, and Merz; participated in Restart Clinical Trial; and is an unpaid board member of American Society of Neurorehabilitation. Farooq Ismail has received honoraria from Allergan/AbbVie and Merz; and is a member of the advisory board of Allergan/AbbVie and Merz. Stephen M. McNeil has received honoraria for lectures/educational events from Ipsen, Merz, and AbbVie; and has received meeting support from Merz. Thomas A. Miller received consulting honoraria, educational and research grants from Allergan/AbbVie, Ipsen, and Merz. Colleen M. O’Connell has received research grants from Annexon, Alexion, Biogen, Calico, Canadian Neurologic Diseases Network, Cytokinetics, Ethicann, Ipsen, Orion, Praxis Spinal Cord Institute, and Roche; received consulting fees for Amylyx, Biogen, Ipsen, MT-Pharma, and Roche; and is an unpaid advisory board member of International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries (ICORD) and Muscular Dystrophy Canada. Rajiv N. Reebye has received honoraria for Allergan/AbbVie, Ipsen, and Merz; has received travel support for Allergan/AbbVie and Merz; and serves on advisory boards for Allergan/AbbVie, Ipsen, and Merz. Lalith E. Satkunam received honoraria from Allergan/AbbVie and Merz; and serves on advisory boards for Allergan/AbbVie, Ipsen, and Merz. Thomas H. Wein has received grants from Allergan/AbbVie and Ipsen; is a consultant for and has received travel support from Allergan/AbbVie; and serves on a committee or advocacy group for American Heart Association, Canadian Stroke Best Practices, and Canadian Stroke Consortium. Paul J. Winston has received grants from Pacira; has received consulting fees, honoraria, and travel support from Allergan/AbbVie, Ipsen, and Pacira.