4.1 Introduction

This chapter describes three very different Irish redress programmes. The Industrial Schools programme operated by the Residential Institutions Redress Board (RIRB) emphasised interactional injuries, had many applicants, a large budget, and high public profile. The RIRB was followed by Caranua, an ancillary programme that redressed the consequences of injurious care. The third programme responded to survivors of Ireland’s Magdalene laundries by addressing structural injuries. Its designers were told, in short, to avoid creating anything like the RIRB.

4.2 The Industrial Schools Programme

In 1999, the television series States of FearFootnote 1 exposed systemic abuse in Ireland’s residential industrial schools. Responding to the resulting public uproar, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern made a public apology on 11 May 1999 in which he announced his intention to set up the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (the Laffoy/Ryan Commission). The commission consisted of two bodies, the Confidential and Investigation Committees. The Confidential Committee heard testimony from survivors in private and without judgement, while the Investigation Committee held inquisitorial public hearings. Almost immediately, solicitors representing large numbers of survivors refused to participate in the Investigation Committee until they were guaranteed a monetary redress programme (Laffoy Reference Laffoy2001: 13).

Acceding to that demand, the Irish government appointed the three- person Compensation Advisory Committee to design a redress programme. No survivor served on the committee. Its 2002 report (The Compensation Advisory Committee 2002) was adopted into statute (‘Residential Institutions Redress Act’ 2002). That Act established the Residential Institutions Redress Board (RIRB) to operate the programme, securing its independence. While the Advisory Committee proceeded, the government negotiated an agreement with the religious orders that operated most industrial schools. The orders paid €128 million in cash and property to the state in exchange for indemnities against survivors who obtained redress. That figure was expected to fund approximately half of the programme’s cost (Committee of Public Accounts 2005: unpaginated). That estimate proved grossly erroneous and politically calamitous.

The RIRB received survivor applications, arranged support for applicants, and adjudicated settlements. Chaired by Justice Esmond Smyth, the RIRB’s twelve board members came from different backgrounds, including law, academia, and social work. Board members were not public servants and membership varied over time. In addition, the RIRB had, at full complement, two full-time and four part-time lawyers and approximately thirty seconded civil servants as administrators. There was no effort to include survivors.

The RIRB’s outreach strategy focussed on broadcast media. Irish news regularly reported on the redress programme and, in addition, the RIRB advertised on television (with an emphasis on sporting events), local radio and newspapers, and tabloid publications (IR Interview 3). The RIRB held early meetings with survivor groups, including émigrés in the United Kingdom. The RIRB developed a well-run website on which the RIRB irregularly published newsletters alongside its annual reports (Residential Institutions Redress Board Undated). To help participants, the RIRB published both short and long guides to the application process. The long guide provided a consistent and authoritative reference, while the shorter version was a more accessible web resource (Residential Institutions Redress Board 2005b, 2003).

The RIRB originally expected 6,500–7,000 applications (Committee of Public Accounts 2005). By September 2015 there were 16,649, of which 15,579 resulted in payment offers (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2016: 27). An eligible application needed to meet five conditions: survivors must apply; be alive on 11 May 1999 (the date of the Taoiseach’s apology); provide identification; evidence of institutional residence; and evidence of injury. Concerning residence, eligible applicants must have stayed at a scheduled institution. Originally 123 institutions were scheduled, the minister of education would add 16 more, bringing the total to 139. Survivors without formal identification could swear an affidavit confirming their identity. Nine cases of apparent misrepresentation were referred to the police, resulting in one prosecution. Men submitted 9,981 applications and women submitted 6,668: a ratio of nearly 60:40 (Residential Institutions Redress Board 2017: 29). That difference might reflect the survivor population, there were more boys than girls in scheduled institutions (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan and Ryan2009). Expatriates lodged nearly 40 per cent of applications.

The programme was open to applicants from January 2003 until December 2005 (thirty-five months). In 2003 and 2004, the RIRB received 2,573 and 2,539 applications, respectively (Residential Institutions Redress Board 2004: 8 and 2005a: 9). Then, in 2005, applications rose to 9,432, of which 3,700 arrived in the two weeks before the closing deadline of 15 December (Residential Institutions Redress Board 2006: 23). The enabling statute provided for late applications under ‘exceptional circumstances’ (‘Residential Institutions Redress Act’ 2002: paragraph 8.2). The courts compelled the RIRB to apply that provision broadly and the RIRB accepted 2,210 late applications. This included a 2009–2010 spike corresponding to the publication of the Commission of Inquiry’s final report and increasing awareness of the lax provisions for late applications (Residential Institutions Redress Board 2010, 2011). The RIRB petitioned the government to legislate the programme’s closure, which it did as of 17 September 2011.

Successful applicants must have experienced one or more of three types of interactional sexual, physical, and emotional abuse. Any act of sexual abuse constituted a basis for claim. Eligible physical abuse must have caused serious damage – explanatory examples include broken limbs, serious scarring, or long-term medical problems. Emotional abuse included sustained fear and verbal denigration and depersonalisation – damaging the survivor’s family relations by, for example, lying to them about their birth names. The programme also redressed structural injuries of wrongful neglect, including impediments to the survivor’s physical, mental, and emotional development such as malnutrition, inadequate education, and insufficient clothing and bedding. For claims of emotional abuse and wrongful neglect, applicants needed to show that abuse caused further physical or psychological harms. Survivors could also claim for ‘loss of opportunity’, which encompassed failing to provide the survivor with the legal minimum of education. Eligibility for loss of opportunity changed depending upon when the applicant was in residence. For example, a failure to receive secondary education became compensable only after free secondary education became available in 1967. Loss of opportunity also encompassed how care experiences damaged the survivors’ career.

***

The RIRB assigned each application to a case officer. The officer assessed the application for completeness and checked to see if an interim payment was appropriate. Interim payments were available for applicants with dementia, a life-threatening disease or similar illness, and for elderly applicants who were born prior to 1 January 1931 (1 January 1933 after 2006). The maximum interim award was €10,000 and its value was deducted from any final award. Those applications were also prioritised for prompt resolution. The RIRB fast-tracked 3,284 applications; 2,886 due to age, 398 on medical or psychiatric grounds (Residential Institutions Redress Board 2017: 31).

The RIRB contacted any person or institution named in the application as an offender. Institutions (usually a religious order) were informed of the identity of the survivor, their claims, and the names of alleged offending persons associated with the institution. Respondent institutions were asked for the contact details of offending persons, who the RIRB would then notify. Named persons or institutions could request a copy of the redress application, excepting medical reports. Institutions would normally provide the RIRB with a written response, which became part of the case file. Alleged offenders and institutional representatives could request a hearing to contest or correct facts alleged in the application. Written responses were normal, but few attended interviews. The findings of the RIRB were confidential and inadmissible in court. Its processes had no legal consequences for offenders.

Most survivors needed care records to compile their application. The industrial schools were supposed to have kept a register of entry. Where those records were missing or inadequate, applicants needed other evidence of residence. Survivors could authorise their lawyers, the RIRB, or another party to search for relevant documents. In cases where no direct documentary evidence of residence was available, applicants could offer corroborating evidence, including memories of institutional personnel, the presence of other survivors, and/or swear an affidavit describing the period of residency.

Written testimony was the primary evidence of abuse, sometimes supplemented by oral testimony at an interview. The application form provided tables for listing injurious incidences (where and why they occurred and who committed them) along with any consequent damage suffered. However, most survivors supplied written narratives. Whatever the format, applicants needed to provide detailed information because the programme assessed severity according to the frequency and duration of abuse and whether different forms of abuse were combined. Claims for damage required medical evidence; therefore, most applications included reports from one or more medical professionals. These reports cost the RIRB around €6 million (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2016: 25). Reports needed to demonstrate that specific illnesses and sequelae were a consequence of experiences in an industrial school. The RIRB contracted medical advisors to review the survivor’s medical evidence. If the advisor disagreed with the applicant’s material, the RIRB would ask for a medical report from a different professional.

***

This was a highly legalistic programme that reflects the influence of some survivors’ lawyers in its development. As related above, the redress programme originated as a response to legal pressure on the Laffoy/Ryan Commission. Those lawyers made influential submissions to the Compensation Advisory Committee (The Compensation Advisory Committee 2002: 7). In effect, the redress programme’s success depended upon its acceptance by lawyers. The scheme reflects their influence: the programme is a structured settlement process modelled on Irish civil law.

The complexity of the redress scheme led the RIRB to encourage applicants to retain legal counsel, which 98 per cent did (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2016: 10). Lawyers mediated most communications between the survivor, record-holding bodies, medical consultants, and the RIRB. The remuneration obtained by lawyers reflects the centrality of their role: the mean average legal fee paid by the RIRB per claim was €12,193Footnote 2 per application, 20 per cent of the average award (Residential Institutions Redress Board 2017: 34). These costs reflect the lawyers’ ability to bill the publicly funded RIRB for any expenses, unconstrained by the usual limits of a private client’s willingness or ability to pay. Yet, the RIRB would only defray the survivor’s legal costs if the survivor accepted a settlement. Survivors who rejected the RIRB’s offer became responsible for their own legal costs – a noteworthy incentive.

Confidential services helped survivors access their records and search for family members. In addition to developing a unit within the Department of Education, the state contracted with Barnardos Ireland to provide the Origins Tracing Services. Origins was built on capacities that Barnardos had developed delivering post-adoption services. As a Protestant organisation, Barnardos had not operated a scheduled institution – it was not an offender. Origins provided records for around 5,000 redress applicants. Some applicants obtained records directly from the religious orders that ran the schools. However, most received their residential records from the Department of Education’s designated unit, via their lawyers. In the early 2000s, the department digitalised all its care records, creating a searchable database. To access their records, the survivor (or their agent) filed a Freedom of Information application asking for a ‘Report by School Number and Pupil Number’ with proof of identification, a privacy authorisation, and whatever information the applicant could provide about their family, their birth identity and date, and the dates of their institutional residence (IR Interview 11). If records were needed quickly, as was the case in the lead up to the programme’s closure in late 2005, the applicant could obtain a provisional indication of residence. In the period 2005–2006, both Origins and the department developed lengthy waiting lists.

In September 2000, the Department of Health established the National Counselling Service for survivors, employing approximately sixty counsellors by November 2001 (The Compensation Advisory Committee 2002: 65). The Catholic Church also provided counselling through its Faoiseamh service, which became Towards Healing in 2011. These services combined direct counselling, by phone or in person, with funding for external therapy. Survivor-led organisations such as One in Four, Aislinn, and Right of Place also offered counselling. In 2001, the state set up a National Office for Victims of Abuse to act as an umbrella organisation to assist survivors, and co-ordinate the work of survivor groups (Department of Education and Skills 2010: 112). However, few groups joined and the office closed in 2006. Funding for survivor support groups continued and totalled around €42 million by the end of 2015 (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2016: 36). The RIRB actively engaged with survivor groups, holding regular consultation meetings. When asked, workers from support agencies attended the board’s interviews with survivors and provided advice and logistical support. For example, Right of Place operated a bed and breakfast facility for survivors who travelled to Cork to meet with lawyers or to attend an interview or settlement conference. The RIRB arranged for Finglas Money Advice and Budgeting Service to provide financial advice to applicants. After 2008, applicants were also referred to Ireland’s Money Advice and Budgeting Service.

***

Applications were assessed by a panel of two board members. The composition of the panel for each application was chosen by lot to help ensure consistency. Panellists held evidentiary interviews with 3,325 applicants – 20 per cent. Interviews were required in any case requiring verbal testimony or to clarify conflicting evidence. An applicant might also request an interview to testify in person. In a small number of cases, and only with the permission of the board, alleged offenders cross-examined applicants. Interviews averaged around two hours in length. Most were held in the RIRB’s offices in southern Dublin. These offices were well-served by public transport and pleasantly mundane in appearance. The RIRB tried to keep interviews informal, although lawyers for the RIRB and the survivor usually attended. The RIRB defrayed the attendance costs for the applicant, counsel, and any support person. Panellists travelled to hold interviews with ill or very elderly applicants. In some cases, the RIRB held interviews in prisons and in psychiatric hospitals; however, this was not the preferred option and the RIRB worked with prisons to enable applicants to attend the RIRB’s more hospitable offices. RIRB held interviews in the United Kingdom for applicants who could not travel to Ireland.

The panel’s first task was to establish the facts of the application. Here, the standard of evidence was a loose plausibility test: if the injuries described by the application were plausible, the RIRB did not interrogate them further (IR Interview 3). However, if the file contained disconfirming evidence, or parts of the application were disputed, the test became the balance of probability and the case would require an evidentiary interview. Panellists used the standards of the day – acts had to be illegal or against policy if they were to be redressable.

Settlement values depended upon both the experience of abuse and the damage caused by that abuse. Panellists assessed the evidence using a fourfold taxonomy of injuries, looking for evidence of abuse, medically verified physical/psychiatric illness, psycho-social damage, and loss of opportunity. Having assessed the evidence, the two-member panel would agree on a provisional numerical score for each component using the ranges indicated in Appendix 3.1. Having scored each component, panellists then tallied the component scores to produce an overall total, using the matrix in Appendix 3.2 to convert the application’s score into euros. The panellists would consider the result. If they thought it inappropriate, they might recalculate the provisional score or, in exceptional cases (fewer than ten), add extra monies up to the value of 20 per cent.

With a provisional value in hand, the RIRB would call a settlement meeting. Settlement meetings were conducted between counsel for the RIRB and the survivor. Although the survivor would usually be present at the office, they were rarely part of the actual negotiations, which were handled by their lawyer. As with evidentiary interviews, the RIRB was responsible for expenses. Originally, the meeting began with the board’s lawyer explaining their provisional assessment. However, after consultation with survivor groups counsel for the applicant were permitted to open negotiations. Negotiations could, and often did, change the provisional assessment, leading to a changed payment offer (IR Interview 3). Most meetings ended with an agreed award value. Once that was complete, the RIRB formally notified the applicant of their settlement offer. Applicants had twenty-eight days to accept or decline the offer or appeal to the Redress Review Committee (appointed by the minister for education). By 2014, the committee had made 571 awards following a review, which increased the original award by an average of 39 per cent (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2016: 26). Applicants could also appeal to the ordinary courts on procedural matters.

Funding for awards came from the Ministry of Education. That funding was not capped. The minister of education approved all awards, but that was a formality; the minister approved RIRB’s every recommendation. Awards were not taxable as income, nor were they intended to affect the survivors’ eligibility for any means-tested benefit. The Act empowered the RIRB to pay the settlement in instalments or place the funds in trust with the courts if they judged the applicant incapable of managing the money.

One interviewee estimated an average (mean) processing time as between eighteen to twenty-four months (Interview 3). However, this depended on the time of submission. In the months leading up to the end of 2005, the programme developed a backlog that took several years to clear. The time it took also depended upon how complicated the application was, the nature of the claims involved, and the evidence available. The programme settled 90 per cent of received applications by 2010. By September 2015, the few remaining cases were no longer in contact with the RIRB. Unable to either pay a settlement or get the claimant to withdraw their application, the RIRB sought and obtained permission from the courts to close those files unilaterally. The last settlements were paid in 2016. Seventeen applicants rejected their awards. There were 1,069 applications withdrawn by applicants, refused by the RIRB, or that resulted in a zero-value award. The average payment was €62,250: 21 per cent of the €300,000 maximum.Footnote 3 The total value of all settlements was €970 million. Legal fees for applicants cost the programme €192.9 million and were paid to 991 legal firms (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2016: 31). Administrative expenses were €69 million (€4,144 per applicant), including internal legal costs. The €1.52 billion total cost of the redress programme was over 600 per cent of the original budget estimate of €250 million.

As a last note, all of the RIRB’s proceedings, including information about awards, were private. The 2002 Act prohibits the publication of ‘any information concerning an application or an award’ in a way that would permit the identification of a person or institution, including survivors (‘Residential Institutions Redress Act’ 2002: §28). This was understood by many survivors to prohibit them from speaking publicly about their experience with the redress programme (Ring Reference Ring2017: 97). However, there have been no prosecutions relating to this provision and it is apparently a legal dead letter.

4.3 Caranua

The Laffoy/Ryan Commission published its final report in 2009. As Ireland suffered through the global financial crisis, the publicity surrounding the report cast light on the RIRB’s burgeoning budgetary exorbitance. Those significant cost overruns triggered vociferous criticism of the 2003 indemnity agreement with religious organisations. Recall that religious organisations had paid €128 million towards the redress scheme, which was estimated at the time to be 50 per cent of the redress programme’s costs. In 2009, the Irish government negotiated an additional €110 millionFootnote 4 from religious orders to endow an ancillary programme. Caranua would supersede an existing fund of €12.7 million providing educational grants to survivors. Unlike the RIRB, Caranua’s funding would be capped, and the programme would close when it exhausted its endowment.

Caranua opened in 2014. It was administratively independent, although the minister of education appointed the nine-member board, four of which were survivors. The board set administrative and staffing policy. In early 2017, Caranua had approximately twenty-three staff, of which eleven were advisors working directly with applicants. This proved inadequate, leading to ‘appalling’ backlogs (Committee of Public Accounts 2017). Most staff had social work and social care backgrounds and were hired directly: they were not public servant secondments (IR Interview 4). Understaffing and the use of temporary contractors led to high levels of turnover between 2014 and 2016.

There was a two-stage application process. First, the survivor applied to verify their eligibility. Eligible survivors must have received a settlement from the RIRB. Caranua had a list of successful claimants; therefore, the initial assessment merely cross-referenced the applicant with that list. The process was simple and quick. Caranua received 6,646 applications to verify eligibility, 6,158 would receive some funding (Caranua 2020a: 17, 3).

The second stage was much more complicated. Caranua sought to assess survivors’ needs holistically and match them with appropriate services. Caranua provided direct funding in three different areas: health and well-being; housing support; and education, learning, and development. As examples, health and well-being services might include optometry or dental work; housing support could include disability modifications, repairs, and home improvements; and education included fees for tertiary education and training. The programme did not fund services available through the public system; therefore, Caranua’s advisors often helped facilitate survivors’ engagement with existing services. Successful applicants had to explain how their application related to injuries that they had experienced while in care. Then an advisor would assess if the service was appropriate to the survivor’s needs and reasonable in terms of cost (Caranua 2016: 11). Where relevant (as in medical services) applications required a professional recommendation and/or a cost quote. Survivors could make multiple applications, repeating the comprehensive assessment each time. Most of Caranua’s money was spent on housing support (e.g. repairs and home improvements), which consumed slightly less than 70 per cent of disbursed funds (Caranua c2019: 3). This created inequities between homeowning survivors and those who were tenants or homeless. Education was the least used category, with grants of around €1.4 million. In total, Caranua paid €97,425,226 million in support for applicants (Caranua c2019: 3), €13,492,282 million was spent on administration (Caranua c2019: 3).

Caranua was a troubled organisation opposed by a vocal group of survivors, many of whom wished to receive the monies directly from the churches (and not pay administrators’ salaries). Conflicts of interest emerged as board members, who were survivors, were also potential beneficiaries of the programme. Some board members became advocates for certain applicants (Interview 4). The programme was launched without any operative regulations and, consequently, the board developed its policy and procedures while in progress, which led to false starts and inconsistencies. Although the programme published guidelines on its website, programme staff were reported to use secret policy documents (Reclaiming Self 2017: Appendix 1). Significant policy changes included expanding the programme to include household goods, funeral costs, and family tracing. In 2016, applicants were given a lifetime limit of €15,000 to prevent a minority of survivors from consuming a disproportionate amount of funding. Continuing criticism led to a major review and in 2017 the government replaced several board members. In 2018, two of the new members left the board while publicly criticising its operations as inefficient and uncaring (Holland Reference Holland2018). The programme closed to new applicants on 1 August 2018 and final payments were made in 2020.

4.4 Magdalene Laundries

The third Irish programme emerged as a reaction to adverse findings in a 2011 UN report (UN Committee Against Torture 2011). Operated by religious orders, Ireland’s Magdalene laundries were workhouses for women. In some cases, the laundries were used as remand facilities (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2010; Finnegan Reference Finnegan2001). All residents were women, and most were young – the median age was twenty (McAleese Reference McAleese2012: xiii). Many residents experienced the laundry as a prison in which they were forced to labour in poor conditions (Smith et al. Reference Smith, O’Rourke, Hill and McGettrick2013: 9). Because the laundries did not admit children, single mothers had to relinquish their children, often to an industrial school.

Ireland responded to the UN’s 2011 report by empanelling an Inter-Departmental Committee chaired by (former) Senator Martin McAleese. The committee reported that approximately 11,198 women resided in a laundry between 1922 and mid-1990s (McAleese Reference McAleese2012: 161). Taoiseach Edna Kenny responded to the committee’s report with a public apology to all Magdalene survivors on 19 February 2013 (Kenny Reference Kenny2013). Kenny’s speech announced that Justice John Quirke would head a commission to design a monetary redress scheme. Quirke’s remit reflected criticisms of the RIRB’s capture by the legal profession. The terms of reference specified that redress funds must be ‘directed only to the benefit of eligible applicants’ and prohibited funding for ‘legal fees and expenses’ (Quirke Reference Quirke2013: 1). Quirke was to report within three months. During that period, survivors could lodge an expression of interest so that they would be informed when the programme opened.

The Magdalene redress programme opened in June 2013 and remains open at the time of writing. The Restorative Justice Implementation Team delivers the programme. Originally housed within the Department of Justice and Equality, the team moved to the Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth in 2020. Its budget is authorised by a vote of the Oireachtas that provides the programme some financial security against intra-ministerial reprioritisation. Operating from a Dublin office, the team was staffed by around nine seconded civil servants. It was initially entirely female, matching the gender profile of the applicants. The team advertised the programme through survivor groups, the departmental website, and Irish embassies. The programme received some media attention; however, the contrast with the high-profile RIRB is clear: before 2018, the Magdalene programme did not have a dedicated website, online information was housed on a subordinate page on a departmental website. Team members did not regularly meet with survivor groups. The programme did not produce annual reports or newsletters, and detailed procedural guidelines were only made public in 2018.

Quirke’s report proposes two bases for monetary payment – residence and unpaid forced labour. Valid applications must satisfy four conditions. Applicants must apply; be alive on 19 February 2013 – the date of Kenny’s apology; provide personal identification; and furnish evidence of residence at a scheduled institution. Posthumous claims are possible if the survivor lodged an application prior to their death. Originally, eligible applicants must have resided in one of ten Magdalene laundries or two ‘training schools’; however, a supplementary process for fourteen further institutions was added after the Ombudsman published a critical programme review (Office of the Ombudsman 2017).

Opened in June 2013, the rate of applications slowed following the first year intake of 756 applications.Footnote 5 Thirty-one were received in the next year and a further twenty the year after. By December 2016, there had been 830 applications. After 2018, the scheme had two streams, the original and the supplementary processes, and fifty-two claims were reassigned to the supplemental process and a review of previously denied claims began. As of 13 December 2019, the original programme had 791 applications and the supplemental process had 115 claims (The Restorative Justice Implementation Team 2021).

Each application was assigned to a case worker, who conducted research and managed contact with the applicant (usually by phone). The application asked for copies of the survivor’s birth certificate, photographic identification, a passport photograph, and their Personal Public Service Number. Survivors were also asked to contact religious orders for documentary evidence of residence. The laundry’s register of entry should record the date, name, and age of the survivor at the time of entry and, sometimes, a release date. For around 50 per cent of applicants, institutional records were insufficient to establish the duration of residence (IR Interview 8). The team divided those applications into three categories (Office of the Ombudsman 2017: 39). Category 1 had a start date of residency, but insufficient information to determine the length of stay. In Category 2 there was evidence of residence, but neither a beginning nor end date. Category 3 had no documentary evidence of residence. Looking more broadly, the team would explore information from multiple sources, including voting, health, education, social insurance, and employment records (IR Interview 8). In cases where documents proved inadequate, the team accepted witness statements and some applicants were invited to informal interviews. Beginning in August 2014, two team members conducted these interviews and produced a report. As of mid-2017, there had been seventy-eight interviews, a little more than 10 per cent of the total.

Applications failed when there was no evidence of residence in a scheduled institution. But that requirement was only publicised in December 2013, after the team had processed several applications. This was one of several gaps between programme design and implementation. The Magdalene laundries were often part of large religious complexes that included several institutions, with people moving around the complex according to the practical demands of the moment. A survivor who, for example, resided in an industrial school and laboured in a laundry might be denied redress. The Ombudsman criticised the post hoc decision to make residence necessary for eligibility (Office of the Ombudsman 2017: 7). Compounding this unfairness, concerns with survivors’ receiving redress twice – from both the RIRB and the Magdalene programme – led policymakers to exclude laundries that had been scheduled in the RIRB (Office of the Ombudsman 2017: 8). However, the conditions of eligibility for the two programmes differ significantly. Unlike the RIRB, the Magdalene programme did not require evidence of abuse or neglect. Therefore, survivors who could not, or did not, tell the RIRB that they were abused were excluded if they had resided and/or worked in an RIRB scheduled laundry. As previously stated, the supplementary programme that started in 2018 added fourteen institutions. It also permitted applications by those who worked in a laundry without having resided in one.

Finally, there were serious concerns regarding the quality of the investigation into cases where there was no documentary evidence of residence. Despite provisions for interviews, in the judgment of the Ombudsman, the programme

… operated on the basis that only women who could demonstrate through available records that they had been officially recorded as admitted to one of the 12 named institutions were eligible.

Personal testimony was not given appropriate weight. While public statements indicated that the survivors’ testimony would be accepted as true, in many cases, testimony that lacked documentary support was rejected by the programme (IR Interview 2; Office of the Ombudsman 2017: 40). Responding to this criticism, in 2018, a barrister, Mary O’Toole, was appointed to review all the cases. She opened a reinvestigation into 214 cases (Ó Fátharta 2016).

***

To receive a redress payment the applicant must waive all claims against the state.Footnote 6 Applicants were eligible for €500 (plus VAT) for legal advice at the point of settlement. The modest provision reflects criticism of RIRB’s legal costs. Indeed, the Quirke Commission had difficulties getting the government to agree to fund any legal advice (IR Interview 10). While applicants could self-fund legal representation earlier in the application process, for the most part, ‘[t]he only time a solicitor is involved, with the Magdalene[s], is when they’re actually at the end of the process and they are signing the waiver’ (IR Interview 9). The timing is important. Funded legal advice was only available after the applicant receives the final payment offer. By that point they would have already agreed to the provisional offer and the lawyer’s task was to check that the survivor understood the consequences of that decision.

There was no specific provision for counselling associated with the scheme. Redress responded to the experience of labour in the laundries, and it was not assumed that participants were thereby traumatised (IR Interview 8). Some survivor groups offered counselling support (IR Interview 9) and any survivor could contact the National Counselling Service; however, there was no extra funding to counsel survivors participating in the scheme. Moreover, the advanced age of many survivors created problems. Unsupported survivors who did not have the capacity to sign legal documents were, in the words of the Ombudsman, ‘forgotten’ (Office of the Ombudsman 2017: 9). Several women died before they were made ‘Wards of Court’ and legally enabled to proceed.

The Quirke report advocates for a dedicated unit to assist Magdalene survivors in perpetuity (Quirke Reference Quirke2013: 45). That never eventuated. The Restorative Justice Team was the primary support, providing personal and logistical support, including records access. The team helped applicants complete their applications, usually by telephone. When survivors received written material from the programme, they could call the team for explanations or seek ad hoc support elsewhere. Some applicants obtained assistance from the Citizens Advice Bureau, either by phone or in person. However, the bureau did not offer a specific service for Magdalene laundry survivors. Although a network of survivor-support agencies volunteered support, none of these organisations received specific funding. Some interviewees observed that the support provided was inadequate (IR Interviews 2 & 9).

***

Case workers with the team decided payment values. Their decisions were approved or revised by a senior officer within the team, and then a manager. The offer was then made to the applicant on a provisional basis. If the applicant agreed, the team issued a formal offer. There was no negotiation, although an applicant who disagreed with the offer could provide further information or appeal. The first level of appeal was inside the department, but outside the team. If the applicant remained unsatisfied, they could appeal to the Ombudsman and/or to the ordinary courts.

Appendix 3.3 describes how claims were assessed for both time in residence and the experience of coerced labour. The redress payments were separate, but not severable – all validated applicants received both payments and the values of both were set by the time they spent living in the institution. The lowest available payment was €11,500 and the highest €100,000. However, policymakers built in protection for survivors that they thought were vulnerable because of their gender, age, (mis)education, and illness (Quirke Reference Quirke2013: 7; IR Interview 5; IR Interview 8). To ensure continuing benefits from the programme, the team converted any lump sum monies in excess of €50,000 to a weekly pension payable for life. Further, because unpaid labour in the laundries did not accrue credit towards Ireland’s contributory pension, the programme provided those who were fifty years or older a pension starting at €100 per week that increased in value each year until the age of sixty-five at which point they move to a value commensurate with the top standard state contributory pension, worth €243.30 per week in 2018. Once settlement was agreed, the pension was payable from 1 August 2013 until the applicant’s death. Lump sum payments are tax exempt and not treated as income, but the contributory pension is reduced by the value of any primary benefits such as housing allowances or similar public support received by the survivor (Shatter Reference Shatter2013). And because the programme is designed to provide stable lifetime support, eligible survivors can access a range of medical and other services through special statutory provision. In another example of a gap between programme design and implementation, the provision of augmented medical services was delayed until 2015. Moreover, the augmented access is less than what Quirke recommended.

The programme aimed to operate as quickly as possible. An application submitted with sufficient documentary evidence of residence could result in a payment offer within weeks (IR Interview 8). By June 2014, the programme had made 369 payments – nearly half the eventual total.Footnote 7 The programme paid 164 claims the next year and 91 in the following. By December 2017 it had made 684 payments. As of November 2020, the original programme had received 791 applications and paid 719 claims, while the supplemental process had received 115 claims and paid 78 (Department of Children 2020). By 2020, €30.128 million had been paid to 788 survivors, a mean average of €38,234.

***

The three Irish redress programmes are a study in contrasts. The RIRB’s massive budgetary overrun constrained subsequent policymakers to design programmes that would avoid similar problems. Caruana’s funding was capped and provided by religious orders. The Magdalene programme worked with a short (until 2017) schedule of twelve institutions and limited lump sum payments to a third of the RIRB’s maximum figure, resulting in a mean average payment that was a little more than half the value of the RIRB’s. The comparative difference in legal fees is even sharper, the €500 maximum in the Magdalene programme is 4 per cent of the RIRB’s €12,193 average. Caranua did not pay for legal fees. Interestingly, one of the Australian programmes considered in the next chapter worked in a very similar manner to Caranua, but largely without criticism. However, the Australians would anticipate the Irish lesson in budgetary exorbitance by capping redress funding.

5.1 Introduction

This chapter explores three Australian redress programmes. Queensland’s Forde Foundation is a small in-kind programme similar to Ireland’s Caranua and was established prior to the more compensatory Queensland Redress. The latter half of the chapter addresses Western Australia’s complicated and troubled Redress WA.

5.2 The Forde Foundation

The 1997 publication of Bringing Them Home (Wilson and Dodson Reference Wilson and Dodson1997) highlighted the roles played by of out-of-home care in the genocide of Australia’s Indigenous Stolen Generations and spurred demands for monetary redress. In response, Queensland established the Commission of Inquiry into Abuse of Children in Queensland Institutions in 1998, known as the Forde Inquiry after its chair Leneen Forde. Finding systemic abuse in out-of-home care, the Forde Report recommended that Queensland establish ‘principles of compensation in dialogue with victims of institutional abuse and strike a balance between individual monetary compensation and provision of services’ (Forde Reference Forde1999: xix).

The Forde Foundation was Queensland’s first response to that recommendation. Set up in 2000 as a perpetual fund, Queensland supplied its capital funding of AUD$4.15 million. The foundation continues to be governed by a government-appointed board whose ten members serve three-year terms. The board attempted to recruit survivors as members, but confronted conflicts of interest (AU Interview 2). The foundation’s three executive positions are supported by state funding. The Public Trustee administers the capital fund and between 2000 and 2019, the foundation distributed over 5,449 grants valued at around AUD$3.16 million (Forde Foundation 2019: 6).

All applicants must be registered with the foundation. Registrants must have been wards of the Queensland State, under its guardianship, or resided as a child in a Queensland institution. Registration is usually straightforward, supported by public records and facilitated by a community agency – Lotus Place (discussed later). There were 2,158 registered survivors in November 2021 (Private Communication from Eslynn Mauritz, Executive Officer of The Forde Foundation, 8 November 2021).

The foundation’s executive officer manages the funding application process. On average, the board receives around 1,000 applications per year, although numbers are increasing. As survivors age, they are more likely to seek more expensive support and, since the foundation is open to anyone who was in care in Queensland, the number of registrants grows every year (Terry Sullivan in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA6). The foundation gives informal priority to those who were in institutional care. There is no limit to the number of applications by any survivor, but they are now restricted to a maximum of AUD$5,000 in funding over five years.

There are three categories of application: dental, health and well-being, and ‘personal development’, which usually concerns education. The foundation will not fund publicly available goods or services, or those otherwise supported by private insurance. Monies are normally disbursed directly to providers. The foundation dispenses approximately AUD$50,000 each quarter, but this varies slightly from year to year to ensure the foundation’s’ perpetual sustainability. Funding decisions are made by a majority vote at the board’s quarterly meetings. Assessment is supposed to be holistic – including information available about the applicant’s life and previous choices, including the content and results of previous awards. However, as each meeting needs to consider around 250 substantial applications, the executive officer generates a short synopsis of each for the board to review (AU Interview 2). In general, dental services are simply approved: other applications receive greater scrutiny (AU Interview 2).

5.3 Queensland Redress

The Forde Foundation was (and is) a modest programme that spends around AUD$200,000 per year. Pressure for more substantive redress mounted throughout the 2000s (AU Interview 3). On 31 May 2007, Queensland announced a AUD$100 million programme for survivors of institutions investigated by the Forde Inquiry (Colvin Reference Colvin2007). A short (June–August) consultation process preceded the programme’s opening on 1 October 2007.

Queensland Redress began with a six-person team called Redress Services (AU Interview 2). The team originally expected 5,000–6,000 applications (Department of Communities 2009: 1). Applications came in quickly, eventually numbering 10,218 (Government of Queensland c2014: 2). Recruitment through secondments increased the staff to around fifty archivists, administrative officers, and project managers. The need to staff positions quickly, with a limited pool of available secondments, led to staffing compromises and high levels of turnover (AU Interview 2). The Department of Communities housed Redress Services, paying approximately AUD$12.3 million in administrative costs.Footnote 1 The department hosted a website (now defunct) with useful information, including the application form, some ‘Frequently Asked Questions’, and the Application Guidelines (Department of Communities 2008). The responsible minister published semi-regular media releases.

Redress Services served as the programme’s back office. The front of shop was Brisbane’s Lotus Place.Footnote 2 Lotus Place is a community centre offering counselling, support for records access and, during the programme, assistance in completing redress applications (AU Interview 1). The Forde Foundation was (and is) collocated at Lotus Place, as is the Aftercare Resource CentreFootnote 3 and, therefore, many Brisbane-based survivors were familiar with Lotus Place before Queensland Redress began, and the staff were equally experienced working with survivors. It is generally held that the work of Lotus Place as a one-stop ‘portal providing consistent information and assisting people [was] outstandingly successful’ (Robyn Eltherington in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA75). However, the number of applicants stretched Lotus Place’s resources. Lotus Place helped ‘over’ 2,000 applicants for redress, around 20 per cent of the total (Karyn Walsh in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA14). The converse is that 80 per cent either had no assistance or used non-funded services such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service. Rural and out-of-state applicants confronted significant accessibility challenges (Senate Community Affairs References Committee 2009: 89).

***

The application deadline was originally 30 June 2008, this was extended to 30 September 2008. Around 3,000 applications were received in that three-month period (Mark Francis in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA71). Received applications were assessed for completeness and survivors were contacted if material was clearly missing, but survivors could not amend their application after 28 February 2009. The programme accepted information in any format and the programme needed an upgraded information management system to manage the complexity of the material it received (AU Interview 2). The brevity of the twelve-month open period means that there are no records of the application rate, although one interviewee suggested that applications arrived steadily and almost immediately as survivor networks spread information about the scheme (AU Interview 2).

Eligibility for Queensland Redress required the applicant to have resided in one of the 159 institutions addressed by the Forde Report. This closed schedule of institutions created inequities, including racial discrimination. Legally, non-Indigenous children could only be placed in licensed institutions; however, some Indigenous children were placed in unlicensed institutions excluded from the Forde Inquiry and the resulting redress programme (AU Interview 3). Still, at the midpoint of the programme, June 2008, 53 per cent of the then 6,655 applicants identified as Indigenous (Lindy Nelson-Carr in ‘Child Safety’ 2008: 59).

Queensland Redress had two pathways, Level 1 and 2. Level 1 provided a uniform payment of AUD$7,000.Footnote 4 Survivors were eligible for a Level 1 payment if they had resided in a scheduled institution, were eighteen years or older on 31 December 1999, and had ‘experienced institutional abuse or neglect’ while in care (Department of Communities 2008: 3). The programme had five categories of abuse: psychological or emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, and ‘systems abuse’, the last referring to structurally injurious practices (Forde Reference Forde1999: iv–v, 12). These categories appeared on the application form as tick box options. To be eligible for a Level 1 payment, applicants needed only to tick a box that indicated they had suffered some form of abuse. Applicants were asked to name the institution(s) in which abuse occurred, then Redress Services would search for evidence of their residence. Residence could have been as short as a single day, but the programme excluded those who were in care during their first year of life only. Applicants needed to provide certified proof of identity (there were some multiple applications) and to authorise Redress Services to access relevant personal records. The information in the application form was confidential.

Care leavers could apply to Level 2 in their initial application or when notified of their Level 1 eligibility. Just under half of applicants (4,802) applied for a Level 1 settlement only. Level 2 responded to more serious injuries, including consequential harms, and required applicants to describe their injurious experiences in detail. The application form provided a short space to describe when injuries occurred and their duration, if the incident was reported, whether the applicant experience(d) consequential damages (the form suggests twenty-nine different harms), and whether medical treatment was sought or received (Department of Communities c2007: 5–6). Applicants were encouraged to submit any relevant documentation, such as police reports or medical statements. Redress Services did not provide funding for professional medical reports or other evidence of injury. This advantaged those who already had medical reports or could pay for them (AU Interview 1). However, most survivors simply described their experience in their own words. Applicants were not told how their information would be used: the assessment policy for Level 2 applications was not developed until after the programme opened to applications. A total of 5,416 survivors applied for a Level 2 payment (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2015b: 118).

A total of 15 per cent of applications to Level 1 were prioritised due to age or illness (Mark Francis in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA71). The programme did not accept posthumous applications, however, it provided AUD$5,000 towards the funeral expenses of those who would have been eligible. As many as 901 applications (9 per cent) were received from out-of-state survivors, but less than 1 per cent of applicants were overseas (Mark Francis in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA78–79). Incarcerated applicants offered a particular challenge. Because the programme accepted postal applications only, Redress Services set up an agreed confidential information system in which letters sent by inmates to the confidential postal address within the Department of Communities would not be read by prison staff. Payments for incarcerated applicants were held in a private trust until their release (AU Interview 3). Although prisoners are not permitted to have cash in prison, they might use the monies outside the prison for purposes within, such as bribery. This also helped imprisoned survivors avoid extortion.

All applications were assessed for a Level 1 payment. Because applicants who indicated an injury on the form were generally believed, Level 1 assessment primarily concerned institutional residence with records provided either by the applicant or sought by Redress Services. Only when no documentary evidence could be found did Redress Services revert to applicants for more information or a statutory declaration (AU Interview 2). Because Level 1 was administratively simple, on average, assessment took about one month (AU Interview 2).

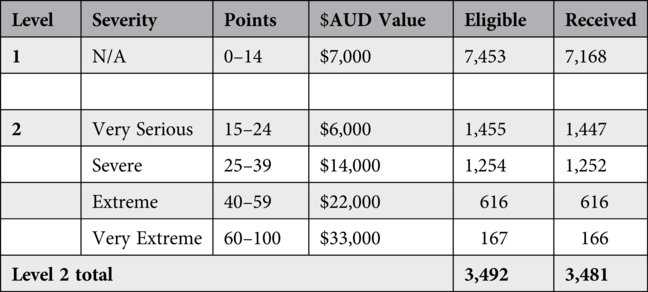

Level 2 assessment began in August 2008, after Level 1 was complete and the programme knew how much remained from the AUD$100 million fund (Senate Community Affairs References Committee 2009: 39). The process required more information, administrative resources, and time. The secretariat compiled a summary of each case file. Applications were then assessed by two members of a six-person panel of contracted lawyers. Those panellists did not conduct interviews (Department of Communities 2009: 3). They matched testimony from the application with evidence available from the Forde Report about the institution. In general, if evidence of residence was available, the programme accepted testimony that matched patterns described in the report (AU Interview 3). The panel then scored the application using a matrix (Appendix 3.3) that divided assessment into seven discrete analyses, giving greater weight to in-care experiences. Once each component was scored, the panellists aggregated the points to assign the application to one of five categories of severity ranging from a null award to ‘very extreme’ (see Table 5.1). The panel chair read the final assessment and verified the outcome.

***

Survivors accessed their records through a Freedom of Information process. Expert staff at Lotus Place provided applicants with support and guidance. Responding to the Forde Report, Queensland had digitised most relevant records. In 2001, Queensland also published Missing Pieces, a directory of the type and location of records held by public and religious bodies (Queensland Department of Families 2001). Those steps helped applicants compile their applications and facilitated cross-referencing. Around 80 per cent of applications were verified using departmental records (AU Interview 2). For the others, Redress Services searched for auxiliary records, such as school registers, and was flexible about the evidence it used (AU Interview 1). Moreover, during the Forde Inquiry, the state developed a ten-person ‘Administrative Release Team’ to respond to records requests (AU Interview 3). This team continued to help survivors access their personal records throughout the 2000s. This meant that a digitalised records-access infrastructure, with experienced staff, was available when the redress programme began.

Survivors confronted challenges in obtaining records nonetheless. Many records had been destroyed and what remained often lacked relevant information. Secrecy concerns surrounding adoption often meant that care staff tried to expunge the child’s relationship with their birth parents from documents. Those concerns also inhibited carers from creating and developing personal records. When relevant information was found, agencies redacted information that was not personal to the survivor. Rebecca Ketton of Aftercare observed ‘that often significant amounts of information is blacked out or crossed out with thick black pen. This can be quite upsetting …’ (‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA39). Redacted information could affect a redress application, if, for example, an offender’s name was withheld. Files often used language hurtful to survivors and many survivors needed counselling support when accessing records (AU Interview 4). Specialist counselling was provided by Aftercare, an initiative of Relationships Australia. Another result of the Forde Inquiry, Aftercare operated a two-person branch in Lotus Place with in-person and telephone counselling. Aftercare also brokered counselling, both privately and through Relationships Australia offices, of which there were forty in 2009. When Queensland Redress ended in 2009, Aftercare had 860 clients, a 200 per cent increase over the term of the programme (Rebecca Ketton in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA42).

Queensland Redress did not pay for legal support during the application process. However, because the programme required survivors to waive all rights against the state for injuries suffered in care, survivors were instructed to obtain legal advice at the point of settlement. Applicants were provided with a list of solicitors willing to provide advice for a set fee (Bligh Reference Bligh2010). Redress Services paid those lawyers directly, at a total cost of AUD$3,468,750 (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2015b: 118).Footnote 5 The waiver only affected the survivor’s rights against Queensland. Financial advice was available to all applicants who accepted a payment. The programme would pay a set fee for an appointment with a financial advisor (Department of Communities 2008). This provision was not well utilised. One interviewee said, ‘We were always really clear about the legal fees and financial advice, but no one took us up on financial advice …’ (AU Interview 2). Kathy Daly reports that no applicant used the financial advice service (Daly Reference Daly2014: 140).

***

In December 2007, applicants began to be notified of their eligibility for Level 1 and sent the abovementioned waiver form. By 13 November 2008, over 3,270 Level 1 payments had been made and by April 2009 the total was over 6,000 – respectively 46 and 84 percent of the 7,168 final total (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2015b: 575). As many as 285 Level 1 payments went unclaimed, mostly by applicants with no known address. Survivors could appeal judgments to the Ombudsman or to the ordinary courts. That review only pertained to the question of institutional residence, never the actual assessment.

All successful Level 2 applicants were notified by letter in August 2009. This synchronised process was encouraged by the funding model in which eligible Level 2 applicants shared the AUD$45,349,000 remaining from the original AUD$100 million (Government of Queensland c2014). However, it also avoided the inequity of some applicants receiving settlements before others.

Every applicant in each of the Level 2’s four categories of severity was paid the same amount. The mean average payment was AUD$12,987, added to the AUD$7,000 for Level 1. Assessment information and monetary values were private; however, survivors were free to discuss their settlements publicly. Redress monies were not treated as income when assessing benefits and taxation. Towards the end of the programme, an issue emerged with Medicare, Queensland’s public health provider. Many survivors obtained redress for injuries for which they had previously received subsidised medical care, and Medicare began processes to recover its treatment costs from redress recipients. To protect survivors, Queensland paid Medicare a lump sum of AUD$500,000 to cover those repayments.

Table 5.1. Queensland Redress payments and values

| Level | Severity | Points | $AUD Value | Eligible | Received |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N/A | 0–14 | $7,000 | 7,453 | 7,168 |

| 2 | Very Serious | 15–24 | $6,000 | 1,455 | 1,447 |

| Severe | 25–39 | $14,000 | 1,254 | 1,252 | |

| Extreme | 40–59 | $22,000 | 616 | 616 | |

| Very Extreme | 60–100 | $33,000 | 167 | 166 | |

| Level 2 total | 3,492 | 3,481 | |||

5.4 Redress WA

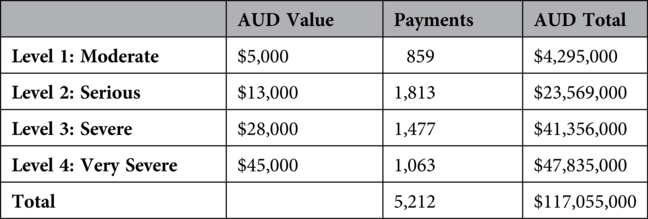

On 17 December 2007, two months after Queensland Redress opened to applications, Western Australia announced a programme providing a Level 1 payment of AUD$10,000 and Level 2 payments up to AUD$80,000. Redress WA’s headline funding of AUD$114 million also looked larger than Queensland’s but it would need to pay the programme’s operational expenses, which would be around AUD$25 million. The programme opened on 1 May 2008 and closed to new applications on 30 April 2009. Then, on 26 June 2009, the government restructured the programme to create four tiers of payment with a maximum of AUD$45,000 (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2014c: 64). Partly a response to the unfolding global financial crisis, the AUD$45,000 maximum better communicated what survivors could reasonably expect, but the change undermined the programme’s credibility and led to vociferous criticism (Green et al. Reference Green, MacKenzie, Leeuwenburg and Watts2013: 2; Pearson, Minty, and Portelli Reference Pearson, Minty and Portelli2015: 7).

The post hoc change to the payment schedule reflected the fact that Redress WA was ‘introduced in an awful hurry’ and ‘with no infrastructure in place’. ‘It wasn’t well planned. It wasn’t planned at all’ (AU Interview 6). In 2007, state policymakers held two consultation meetings, but the development process lacked meaningful stakeholder involvement (Kimberley Community Legal Services c2012: 5; AU Interview 6). Located in the (relatively new) Department of Communities, when it opened in May 2008, Redress WA had fewer than ten staff. By 2010, the complement was around 130, yet the programme was never fully staffed. Most were seconded civil servants, but the demand for staff led to staffing compromises and the use of short-term contractors, contributing to high levels of turnover (AU Interview 8). This, in turn, led to administrative delays and high workloads that further aggravated staffing problems. Work was also hindered by a ‘clumsy and slow’ data management system (Western Australian Department for Communities Reference Rockc2012: 13). Delays frustrated claimants, leading to more complaints and hostility from many survivors (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 8). Redress WA did not have a publicly accessible office and staff were anonymised to shield them from media criticism and security threats. In the opinion of one interviewee, that made them ‘invisible’, with detrimental consequences for survivors (AU Interview 6).

Redress WA’s publicity strategy developed over time (Redress WA Reference Redress2008b). Originally, the programme expected 9,689 eligible applications (Redress WA Reference Redress2008b: 7). But the programme initially received much fewer than expected (only 328 applications by 31 August 2008) and the programme revised its publicity efforts, with more advertising (Rock Reference Rock2008: 5; Redress WA Reference Redress2008b: 11). Redress WA operated a website with useful information about the application process, available support, and updates on the programme. The programme produced a small number of newsletters, which it sent to registered applicants and published on its website.

Eligible applicants had to apply before 30 April 2009, with those who lodged an application having a further two months to complete it (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 17). Approximately 50 per cent of applications were submitted incomplete: some service providers simply submitted lists of names (AU Interview 9). Programme staff then had to contact applicants to complete missing information. Some service providers in remote Indigenous communities requested permission to submit late applications for survivors involved with traditional lore or sorry business,Footnote 6 and for those adversely affected by widespread flooding (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 10). Redress WA received 171 late applications, 27 were accepted.

Compensable injuries included physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse, and/or neglect (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 5). Applicants had to be eighteen on 30 April 2009, the original closing date of the programme. Applicants without identification documents could provide written statements from two referees. The programme did not have a schedule of specific institutions, but the state must have had formal responsibility for the survivor’s residential care at the time of the injury, which must have been prior to 1 March 2006. This was a firm parameter. Redress WA rejected applicants who had been informally placed in out-of-home care, this disproportionately affected Indigenous applicants (AU Interviews 8 & 9).

Redress WA accepted 5,917 applications for assessment. The application flow was marked by a significant increase during April–July 2009, when the programme received nearly 50 per cent of the final total (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 16). Western Australian residents submitted almost 90 per cent of the programme’s applications – half came from rural and/or remote areas: 42 per cent of applicants were under fifty years, and 49 per cent were male (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 3). Indigenous survivors submitted 3,024 (51 per cent) of applications. Former child migrants submitted 768 (13 per cent). Other groups were underrepresented, possibly because they lacked effective support organisations (‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009b: 50). The eligibility requirement of having been ‘in state care’ may have dissuaded survivors of religious institutions who did not know they had been legally wards of the state (AU Interview 6).

Applications were prioritised if applicants had a terminal illness (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 26). Redress WA made 791 priority settlements of up to AUD$10,000 (‘Extract from Hansard, Hon Robyn McSweeney’ Reference McSweeney2010). Overpayments were not recovered. In September 2009, after twenty-nine applicants had died, the programme began to pay AUD$5,000 to the estates of deceased claimants (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 7). As many as 167 applicants passed away during the programme.

The fourteen-page application form asked survivors to describe the injuries they suffered and the consequential harms they incurred, along with time and place of any residence. Officials believed that less structure would encourage applicants to provide more accurate information. To avoid priming applicants, the form did not list potential forms of abuse or neglect, it simply asked applicants to provide ‘as much detail as possible’ (Redress WA Reference Redressc2008: 4). Most evidence was narrative, often handwritten, although other relevant documentation might be appended.

Completed applications were placed on a waiting list before the research team began to verify care placements. Redress WA undertook to search institutional records. This preliminary research might uncover other relevant material; however, ‘because of time pressures, the principal focus was verifying [residence in] state care’ (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 20). Redress WA compiled dossiers on larger care institutions. These dossiers gave a brief overview of the institution’s history; a summary of relevant policy and regulation; contemporary evidence of violations, including characteristic forms of abuse and neglect; and a list of alleged perpetrators. This was followed by summary information, for example, the institutional history of Bindoon Boys Town states ‘… sexual abuse was particularly rife in the late 1940s and through the 1950s’ (Redress WA 2008/Reference Redress2009: 7). That short statement offered supporting evidence for survivors who claimed that they were sexually abused in that period. The summary also noted typical aggravating factors, such as the frequency of vicious public punishment. The dossier might conclude with some references and photos. Dossiers varied in quality. None were substantial and smaller placements would have less-developed dossiers – foster care was excluded. Where possible, assessors batched applications by institution and time. This facilitated the use of similar fact evidence, as specific perpetrators might be mentioned in multiple applications. However, this batching could only be partial, as most applicants had resided in more than one institution.

Contemporarily accepted abuse and legal injuries, such as caning, were not eligible. Applying the standards of the day, education was similarly assessed – for example, leaving school at the age of fourteen was not injurious (Government of Western Australia 2010: 19). Indigenous survivors of the Stolen Generations were not compensated for having been removed from their culture, but elements relevant to injurious cultural removal might comprise consequential harm and/or be compounding and aggravating factors (Government of Western Australia 2010: 13–14). Initially, any award of more than AUD$10,000 required a psychological report, paid for by Redress WA (‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009b: 54). This changed in 2010 and only applications assessed at Level 4 (AUD$45,000) needed medical evidence of injuries (AU Interview 8). If there was uncertainty whether the application was at Level 4, Redress WA might pay for a medical report, but the programme did not otherwise defray legal or medical costs. This after-the-fact change in policy meant that many applicants submitted unnecessary material, including psychological tests (Green et al. Reference Green, MacKenzie, Leeuwenburg and Watts2013: 4; AU Interview 6).

Having reviewed the application, institutional history, and any other relevant evidence, the case worker interviewed the applicant by telephone. During the interview, survivors could add information and interviewers might prompt applicants to provide relevant information, if, for example, research had uncovered a placement the applicant did not mention (AU Interview 9). In addition, the interviewer would seek clarification of, and evidence regarding, abuses or consequential harms described in the application. As some time had usually passed between the original application and the interview, new information was often available, including personal or medical records. These interviews helped moderate the variable quality of the initial applications, particularly for applicants with poor literacy (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 9).

Applicants were never interviewed in person. An internal document suggests that in-person hearings would be too stressful and ‘a form of secondary abuse in some cases’ (Government of Western Australia 2010: 12). Moreover, attendees at a hearing might seek legal representation, which would increase costs. Because telephone interviews could also retraumatise applicants, applicants could indicate that they did not want to receive a telephone call (Redress WA Reference Redressc2008: 2). These survivors were notified by letter when their application was assessed and invited to provide further information. Redress WA developed protocols to protect the privacy and quality of these interviews. But this preparatory work was not always successful.

What I heard time and time again was people saying, ‘Oh, I had my cousins over for lunch and I got a phone call, and it was the lady from Redress WA wanting to talk about my abuse and wanting more details about how I was sexually abused.’ Often, survivors aren’t assertive with authority, so they don’t say, ‘Well, can you ring back later’ or ‘Can we set up a time to do this later?’ So, they would just feel obliged to talk about really intimate and painful memories on the spot. That wasn’t fair …

Having assembled the facts, the case worker scored the application using a matrix (Appendix 3.6). This matrix was not published until after the programme closed to new applications. Assessors used four components: the experience of abuse and/or neglect; compounding factors, such as how isolated the resident was when abused; consequential harms; and aggravating factors, such as degrading treatment. Each component was worth twenty points. Redress WA developed a table (Appendix 3.7) to gauge injurious experiences, using indicative descriptions to help assessors score applicants according to severity. By subdividing each application into several categories, each comprised of various factors, Redress WA tried to capture individual nuance while retaining consistency. Assessors were encouraged to holistically reflect on the outcomes (Government of Western Australia 2010: 8–10).

Although the general categories of abuse and neglect match information sought on the application form, applicants were not told how the programme would assess severity. Moreover, the application form is silent concerning the role of compounding and aggravating factors. The form asks for information about consequential harm, but it does not mention salient subcategories. Some of this information might have been sought during the telephone interview, but it remains true that assessors used information that was only partially related to evidence requested by the application form. This non-transparency responded to widespread worries that survivors might tailor their testimony so as to obtain higher settlements (AU Interview 9). Peter Bayman, the programme’s senior legal officer, told a Senate Inquiry that ‘[w]e did not want to design a scale [for assessment] and then publish it so that it became essentially a cheat sheet’ (‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009b: 56). Moreover, the assessment guidelines were not compiled until October 2008 – nearly six months after the programme opened – with the fourth and final version confirmed in May 2011 (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 41).

The case worker’s initial assessment was submitted to a team leader, who would reprise the assessment. If the totals varied, the judgement of the team leader was generally decisive (AU Interview 9). If an applicant was near the minimum score for a higher-level payment, they would often get moved up. Then, a senior research officer produced a ‘Notice of Assessment Decision’, that summarised the application and graded its severity. The programme notified applicants who were to be declined that they had twenty-eight days to provide further information. Applications categorised as severe or very severe were assessed a fourth time by an ‘Internal Member’ who was a lawyer. Internal members examined both the application and the assessment process, they might, for example, review the telephone interview transcript for evidence of leading questions (AU Interview 9). That fourth assessment could result in further requests for information or change the severity assessment. Once satisfied, the internal member submitted a report to the four-person Independent Review Panel that assessed the application again (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 20). The Review Panel did not need to use the matrices and could take a holistic view of the application. When it disagreed with the internal member, the panel tended to increase the settlement value (AU Interviews 8 & 9). Senior staff moderated the whole process to ensure that total costs would not exceed the capital funding. However, on 29 August 2011 the government provided a further AUD$30 million to cover any cost overruns.

With respect to evidentiary standards, Redress WA variously claimed to presumptively believe all claims by applicants (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 8); to have applied the standard of ‘reasonable likelihood’ (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 12); and to have tested evidence according to the ‘balance of probabilities’ (Government of Western Australia 2010: 11). In short, the standard applied depended on the payment value. Applicants pegged for lower level payments benefitted from a presumption of truth, (AU Interview 9), however, higher payments were assessed on the balance of probabilities (Government of Western Australia 2010: 31).

***

Twenty-six agencies were initially contracted to support applicants, with more engaged over time (Government of Western Australia 2007; Western Australian Department for Communities; c2012; Department for Communities 2009: 42). Redress WA published a booklet titled ‘Support Services for WA Care Leavers’ in November 2009 (Redress WA Reference Redress2009). Organisations were contracted to provide up to twelve hours of assistance for each survivor (Green et al. Reference Green, MacKenzie, Leeuwenburg and Watts2013: 4). The demands on key support services were significant. The Aboriginal Legal Service (ALS) submitted over 1,000 applications (Barter, Razi, and Williams Reference Barter, Razi and Williams2012: 7–10). Indeed, overwhelmed by the demand, at one point the ALS stopped accepting new clients (AU Interview 6). At one step removed, Redress WA’s helpdesk provided information to both applicants and service providers, receiving 500 calls, 100 emails, and about 20 text messages each week (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 4).

Redress WA received variable reviews concerning the support provided (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2014c: 66). For one survivor

… with Redress, you had people on your side offering you information, support. And, sure, there was a financial thing at the end of it, which was wonderful, but it was the fact that we had qualified counsellors in proper settings, a myriad of people we could call if we had any questions – they were on tap sort of 24 hours a day, seven days a week – and that did help immensely.