Since the term was first coined in the late 1990s during a presentation about the benefit of radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags in the retail sector, the “Internet of Things” (IoT) has promised a smart, interconnected global digital ecosystem enabling your toaster to text you when your breakfast is ready, and your sweatshirt to give you status updates during your workout. This rise of “smart products” such as internet-enabled refrigerators and self-driving cars holds the promise to revolutionize business and society. But the smart wave will not stop with stuff owing to related trends such as the “Internet of Bodies” now coming into vogue (Atlantic Council, 2017). It seems that, if anything, humanity is headed toward an “Internet of Everything,” which is a term that Cisco helped to pioneer (Reference EvansEvans, 2012).

The Internet of Everything (IoE) takes the notion of IoT a step further by including not only the physical infrastructure of smart devices but also its impacts on people, business, and society. Thus, the IoE may be understood as “the intelligent connection of people, process, data and things[,]” whereas IoT is limited to “the network of physical objects accessed through the Internet” (Reference BanafaBanafa, 2016). This broader lens is vital for considering the myriad security and privacy implications of smart devices becoming replete throughout society, and our lives. Other ways to conceptualize the problem abound, such as Bruce Schneier’s notion of Internet+, or Eric Schmidt’s contention that “the Internet will disappear” given the proliferation of smart devices (Reference GilesGiles, 2018). Regardless, the salient point is that our world is getting more connected, if not smarter, but to date governance regimes have struggled to keep pace with this dynamic rate of innovation.

Yet it is an open question whether security and privacy protections can or will scale within this dynamic and complex global digital ecosystem, and whether law and policy can keep up with these developments. As Schneier has argued:

The point is that innovation in the Internet+ world can kill you. We chill innovation in things like drug development, aircraft design, and nuclear power plants because the cost of getting it wrong is too great. We’re past the point where we need to discuss regulation versus no-regulation for connected things; we have to discuss smart regulation versus stupid regulation.

The natural question, then, is whether our approach to governing the IoE is, well, smart? This chapter explores what lessons the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) and Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) frameworks hold for promoting security, and privacy, in an IoE, with special treatment regarding the promise and peril of blockchain technology to build trust in such a massively distributed network. Particular attention is paid to governance gaps in this evolving ecosystem, and what state, federal, and international policies are needed to better address security and privacy failings.

The chapter is structured as follows. It begins by offering an introduction to the IoE for the uninitiated, and continues by applying the IAD and GKC frameworks, emphasizing their application for the IoE. The utility of blockchain technology is next explored to help build trust in distributed systems before summarizing implications for managers and policymakers focusing on the intersection between polycentric governance and cyber peace.

8.1 Welcome to the Internet of Everything

As ever more stuff – not just computers and smartphones, but thermostats and baby monitors, wristwatches, lightbulbs, doorbells, and even devices implanted in our own bodies – are interconnected, the looming cyber threat can easily get lost in the excitement of lower costs and smarter tech. Indeed, smart devices, purchased for their convenience, are increasingly being used by domestic abusers as a means to harass, monitor, and control their victims (Reference BowlesBowles, 2018). Yet, for all the press that the IoT has received, it remains a topic little understood or appreciated by the public. One 2014 survey, for example, found that fully 87% of respondents had never even heard of the “Internet of Things” (Reference MerrimanMerriman, 2014). Yet managing the growth of the IoE impacts a diverse set of interests: US national and international security; the competitiveness of firms; global sustainable development; trust in democratic processes; and safeguarding civil rights and liberties in the Information Age.

The potential of IoT tech has arguably only been realized since 2010, and is arguably the result of the confluence of at least three factors: (1) the widespread availability of always-on high-speed Internet connectivity in many parts of the world; (2) faster computational capabilities permitting the real-time analysis of Big Data; and (3) economies of scale lowering the cost of sensors and chips to manufacturers (Shackelford, 2017). However, the rapid rollout of IoT technologies has not been accompanied by any mitigation of the array of technical vulnerabilities across these devices, highlighting a range of governance gaps that may be filled in reference to the Ostrom Design Principles along with the IAD and GKC frameworks.

8.2 Applying the IAD and GKC Frameworks to the Internet of Everything

The animating rationale behind the IAD framework was, quite simply, a lack of shared vocabulary to discuss common governance challenges across a wide range of resource domains and issue areas (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014). “Scholars adopting … [the IAD] framework essentially commit to ‘a common set of linguistic elements that can be used to analyze a wide diversity of problems,’” including, potentially, cybersecurity and Internet governance. Without such a framework, according to Professor Dan Cole, confusion is common, such as in defining “resource systems” that can include “information, data, or knowledge” in the intellectual property context, with natural resources (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 51). In the Internet governance context, similar confusion surrounds core terms such as “cyberspace,” “information security,” and “cybersecurity (Reference ShackelfordShackelford, 2014). There are also other more specialized issues to consider, such as defining what constitutes “critical infrastructure,” and what if any “due diligence” obligations operators have to protect it from cyber attackers. Similarly, the data underlying these systems is subject to a range of sometimes vying legal protections. As Professor Cole argues, “[t]rade names, trade secrets, fiduciary and other privileged communications, evidence submitted under oath, computer code, and many other types of information and flows are all dealt with in various ways in the legal system” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 52).

Although created for a different context, the IAD framework can nevertheless improve our understanding of data governance, identify and better understand problems in various institutional arrangements, and aid in prediction under various alternative institutional scenarios (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014). Indeed, Professor Ostrom believed that the IAD framework had wide application, which has been born out given that it is among the most popular institutional frameworks used in a variety of studies, particularly those focused on natural commons. The IAD framework is unpacked in Figure 8.1, and its application to IoE governance is analyzed in turn, after which some areas of convergence and divergence with the GKC framework are highlighted.

Figure 8.1 The Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework

It can be difficult to exclude users from networks, especially those with valuable trade secrets, given the extent to which they present enticing targets for both external actors and insider threats. With these distinctions in mind, Professor Brett Frischmann, Michael Madison, and Katherine Strandburg have suggested a revised IAD framework for the knowledge commons reproduced in Figure 8.2.

Figure 8.2 The Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) framework

Space constraints prohibit an in-depth analysis of the myriad ways in which the GKC framework might be useful in conceptualizing an array of security and privacy challenges in the IoE, but nevertheless a brief survey is attempted later. In brief, the distinctions with this approach, as compared with the traditional IAD framework, include (1) greater interactions on the left side of the chart underscoring the complex interrelationships in play; (2) the fact that the action area can similarly influence the resource characteristics and community attributes; and (3) that the interaction of rules and outcomes in knowledge commons are often inseparable (Reference FrischmannFrischmann, Madison and Strandburg, 2014, 19). These insights also resonate in the IoE context, given the tremendous amount of interactions between stakeholders, including IoT device manufacturers, standards-setting bodies, regulators (both national and international), and consumers. Similarly, these interactions are dynamic, given that security compromises in one part of the IoE ecosystem can lay out in a very different context, as seen in the Mirai botnet, in which compromised smart light bulbs and other IoE devices were networked to crash critical Internet services (Reference BotezatuBotezatu, 2016).

The following subsections dive into various elements of the GKC framework in order to better understand its utility in conceptualizing IoE governance challenges.

8.2.1 Resource Characteristics and Classifying Goods in Cyberspace

Digging into the GKC framework, beginning on the left side of Figure 8.2, there are an array of characteristics to consider, including “facilities through which information is accessed” such as the Internet itself, as well as “artifacts … including … computer files” and the “ideas themselves” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 10). The “artifacts” category is especially relevant in cybersecurity discussions, given that it includes trade secrets protections, which are closer to a pure private good than a public good and are also the currency of global cybercrime (Reference Shackelford, Proia, Craig and MartellShackelford et al., 2015). Internet governance institutions (or “facilities” in this vernacular) can also control the rate at which ideas are diffused, such as through censorship taking subtle (e.g., YouTube’s decision to take down Nazi-themed hate speech videos) or extreme (e.g., China’s Great Firewall) forms (Reference BeechBeech, 2016).

There is also a related issue to consider: what type of “good” is at issue in the cybersecurity context? In general, goods are placed into four categories, depending on whether they fall on the spectra of exclusion and subtractability (Reference BuckBuck, 1998). Exclusion refers to the relative ease with which goods may be protected. Subtractability evokes the extent to which one’s use of a good decreases another’s enjoyment of it. If it is easy to exclude others from the use of a good, coupled with a high degree of subtractability, then the type of good is likely to be characterized as “private goods” that are defined by property law and best regulated by the market (Reference Hiller and ShackelfordHiller and Shackelford, 2018). Examples in the IoT context are plentiful, from smart speakers to refrigerators. Legal rights, including property rights, to these goods include the right of exclusion discussed above. At the opposite end of the spectrum, where exclusion is difficult and subtractability is low, goods are more likely characterized as “public goods” that might be best managed by governments (Reference Ostrom, Ostrom, Cole and McGinnisOstrom and Ostrom, 2015). An example is national defense, including, some argue, cybersecurity (Reference OstromOstrom, 2009). This is an area of some debate, though, given the extensive private sector ownership of critical infrastructure, which makes drawing a clear line between matters of corporate governance and national security difficult.

In its totality, the IoE includes all forms of goods, including private devices and municipal broadband networks, catalyzing a range of positive and negative externalities from network effects to cyberattacks. For example, the IoE includes digital communities as a form of club good, with societies being able to set their own rights of access; a contemporary example is the efforts of Reddit moderators to stop trolls, limit hate speech, and promote a more civil dialogue among users (Reference RooseRoose, 2017). Such communal property rights may either be recognized by the state, or be based on a form of “benign neglect” (Reference BuckBuck, 1998, 5). Indeed, as of this writing, there is an active debate underway in the United States and Europe about the regulation of social-media platforms to limit the spread of terrorist propaganda, junk news, sex trafficking, and hate speech. Such mixed types of goods are more the norm than the exception. As Cole has argued:

[S]ince the industrial revolution it has become clear that the atmosphere, like waters, forests, and other natural resources, is at best an impure, subtractable, or congestible public good. As such, these resources fall somewhere on the spectrum between public goods, as technically defined, and club or toll goods. It is such impure public goods to which Ostrom assigned the label “common-pool resources”.

Naturally, the next question is whether, in fact, cyberspace may be comparable to the atmosphere as an impure public good, since pure public goods do not present the same sort of governance challenges, such as the well-studied “tragedy of the commons” scenario, which predicts the gradual overexploitation of common pool resources (Reference Feeny, Berkes, Mccay and AchesonFeeny et al., 1990). Though cyberspace is unique given that it can, in fact, expand such as through the addition of new networks (Jordan, 1990), increased use also multiplies threat vectors (Reference DeibertDeibert, 2012).

Solutions to the tragedy of the commons typically “involve the replacement of open access with restricted access and use via private property, common property, or public property/regulatory regimes” (Reference FrischmannFrischmann, Madison, and Strandburg, 2014, 54). However, in practice, as Elinor Ostrom and numerous others have shown, self-organization is in fact possible in practice, as is discussed later (Reference FrischmannFrischmann, 2018). The growth of the IoE could hasten such tragedies if vulnerabilities replete in this ecosystem are allowed to go unaddressed.

8.2.2 Community Attributes

The next box element on the left side of the GKC framework, titled “Attributes of the Community,” refers to the network of users making use of the given resource (Reference SmithSmith, 2017). In the natural commons context, communities can be macro (at the global scale when considering the impacts of global climate change) or micro, such as with shared access to a forest or lake. Similarly, in the cyber context, communities come in every conceivable scale and format from private pages on Facebook to peer-to-peer communities to the global community of more than four billion global Internet users as of October 2018, not to mention the billions of devices comprising the IoE. Even such a broad conceptualization omits impacted non-user stakeholders and infrastructure, as may be seen in the push to utilize 5G connectivity, AI, and analytics to power a “safe city” revolution, albeit one built on Huawei architecture. The scale of the multifaceted cyber threat facing the public and private sector parallels in complexity the battle to combat the worst effects of global climate change (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014; Reference ShackelfordShackelford, 2016). Such a vast scale stretches the utility of the GKC framework, which is why most efforts have considered subparts, or clubs, within this digital ecosystem.

An array of polycentric theorists, including Professor Ostrom, have extolled the benefits of small, self-organized communities in the context of managing common pool resources (Reference Ostrom, Burger, Field, Norgaard and PolicanskyOstrom, 1999). Anthropological evidence has confirmed the benefits of small-scale governance. However, micro-communities can ignore other interests, as well as the wider impact of their actions, online and offline (Reference MurrayMurray, 2007). A polycentric model favoring bottom-up governance but with a role for common standards and baseline rules so as to protect against free riders may be the best-case scenario for IoE governance, as is explored further. Such self-regulation has greater flexibility to adapt to dynamic technologies faster than top-down regulations, which even if enacted, can result in unintended consequences, as seen now in the debates surrounding California’s 2018 IoT law. As of January 2020, this law would require “any manufacturer of a device that connects ‘directly or indirectly’ to the Internet … [to] equip it with ‘reasonable’ security features, designed to prevent unauthorized access, modification, or information disclosure” (Reference RobertsonRobertson, 2018). Yet, it is not a panacea, as we will see, and there is plentiful evidence that simple rule sets – especially when they are generated in consultation with engaged and empowered communities – can produce better governance outcomes.

8.2.3 Rules-in-Use

This component of the GKC framework comprises both community norms along with formal legal rules. One of the driving questions in this area is identifying the appropriate governance level at which to formalize norms into rules, for example, whether that is at a constitutional level, collective-choice level, etc. (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 56). That is easier said than done in the cybersecurity context, given the wide range of industry norms, standards – such as the National Institute for Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF) – state-level laws, sector-specific federal laws, and international laws regulating everything from banking transactions to prosecuting cybercriminals. Efforts have been made to begin to get a more comprehensive understanding of the various norms and laws in place, such as through the International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU)’s Global Cybersecurity Index and the Carnegie Endowment International Cybersecurity Norms Project, but such efforts remain at an early stage of development. A variety of rules may be considered to help address governance gaps, such as position and choice rules that define the rights and responsibilities of actors, such as IoT manufacturers and Internet Service Providers (ISPs), as is shown in Table 8.1 (Reference Ostrom, Crawford and OstromOstrom and Crawford, 2005). Given the degree to which core critical infrastructure – such as smart grids and Internet-connected medical devices – are also subsumed within IoT debates, there is a great deal of overlap between potential rule sets from incentivizing the use of cybersecurity standards and frameworks, as is happening in Ohio to hardening supply chains.

Table 8.1 Types of rules

| Aggregation rules | Determine whether a decision by a single actor or multiple actors is needed prior to acting at a decision point in a process. |

|---|---|

| Boundary rules | Define:

|

| Choice rules | Define what actors in positions must, must not, or may do in their position and in particular circumstances. |

| Information rules | Specify channels of communication among actors, as well as the kinds of information that can be transmitted between positions. |

| Payoff rules | Assign external rewards or sanctions for particular actions or outcomes. |

| Position rules | Define positions that actors hold, including as owners of property rights and duties. |

Many of these rules have cyber analogues, which emphasize cybersecurity information sharing through public–private partnerships to address common cyber threats, penalize firms and even nations for lax cybersecurity due diligence, and define the duties – including liability – of actors, such as Facebook and Google (Reference ReardonReardon, 2018).

The question of what governance level is most appropriate to set the rules for IoT devices is pressing, with an array of jurisdictions, including California, pressing ahead. For example, aside from its IoT-specific efforts, California’s 2018 Consumer Privacy Act is helping to set a new transparency-based standard for US privacy protections. Although not comparable to the EU’s new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) discussed later, it does include provisions that allow consumers to sue over data breaches, including in the IoT context, and decide when, and how, their data is being gathered and used by companies (Reference AdlerAdler, 2018). Whether such state-level action, even in a state with an economic footprint as the size of California, will help foster enhanced cybersecurity due diligence across the broader IoE ecosystem remains to be seen.

8.2.4 Action Arenas

The arena is just that, the place where decisions are made, where “collective action succeeds or fails” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 59). Such arenas exist at three levels within the GKC framework – constitutional, collective-choice, and operational. Decisions made at each of these governance levels, in turn, impact a range of rules and community attributes, which is an important feature of the framework. Examples of decision-makers in each arena in the cybersecurity context include (1) at the constitutional level, judges deciding the bounds of “reasonable care” and “due diligence” (Reference Shackelford, Richards, Raymond and CraigShackleford, 2015); (2) federal and state policymakers at the collective-choice (e.g., policy) level, such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) policing unfair and deceptive trade practices; and (3) at the operational level, firms, households, and everyone else.

8.2.5 Evaluation Criteria

The final component, according to Cole, is “the most neglected and underdeveloped” of the frameworks (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 62). Elinor Ostrom, for example, offered the following “evaluative criteria” in considering how best to populate it, including “(1) economic efficiency; (2) fiscal equivalence; (3) redistributional equity; (4) accountability; (5) conformance to values of local actors; and (6) sustainability” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 62). In the GKC context, these criteria might include “(1) increasing scientific knowledge; (2) sustainability and preservation; (3) participation standards; (4) economic efficiency; (5) equity through fiscal equivalence; and (6) redistributional equity” (Reference MurrayHess and Ostrom, 2007, 62). This lack of rigor might simply be due to the fact that, in the natural commons context, the overriding goal has been “long-run resource sustainability” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 62). It is related, in some ways, to the “Outcomes” element missing from the GKC framework but present in the IAD framework, which references predictable outcomes of interactions from social situations, which can include consequences for both resource systems and units. Although such considerations are beyond the findings of the IAD framework, in the cybersecurity context, an end goal to consider is defining and implementing cyber peace.

“Cyber peace,” which has also been called “digital peace,” is a term that is increasingly used, but it also remains an arena of little consensus. It is clearly more than the “absence of violence” online, which was the starting point for how Professor Johan Galtung described the new field of peace studies he helped create in 1969 (Reference GaltungGaltung, 1969). Similarly, Galtung argued that finding universal definitions for “peace” or “violence” was unrealistic, but rather the goal should be landing on an apt “subjectivistic” definition agreed to by the majority (Reference GaltungGaltung, 1969, 168). He undertook this effort in a broad, yet dynamic, way recognizing that as society and technology changes, so too should our conceptions of peace and violence. That is why he defined violence as “the cause of the difference between the potential and the actual, between what could have been and what is” (Reference GaltungGaltung, 1969, 168).

Cyber peace is defined here not as the absence of conflict, what may be called negative cyber peace. Rather, it is the construction of a network of multilevel regimes that promote global, just, and sustainable cybersecurity by clarifying the rules of the road for companies and countries alike to help reduce the threats of cyber conflict, crime, and espionage to levels comparable to other business and national security risks. To achieve this goal, a new approach to cybersecurity is needed that seeks out best practices from the public and private sectors to build robust, secure systems, and couches cybersecurity within the larger debate on Internet governance. Working together through polycentric partnerships of the kind described later, we can mitigate the risk of cyber war by laying the groundwork for a positive cyber peace that respects human rights, spreads Internet access along with best practices, and strengthens governance mechanisms by fostering multi-stakeholder collaboration (Reference Galtung and ChristieGaltung, 2012). The question of how best to achieve this end is open to interpretation. As Cole argues, “[f]rom a social welfare perspective, some combination of open- and closed-access is overwhelmingly likely to be more socially efficient than complete open or close-access” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 61). Such a polycentric approach is also a necessity in the cyber regime complex, given the prevalence of private and public sector stakeholder controls.

In the cybersecurity context, increasing attention has been paid identifying lessons from the green movement to consider the best-case scenario for a sustainable cyber peace. Indeed, cybersecurity is increasingly integral to discussions of sustainable development – including Internet access – which could inform the evaluative criteria of a sustainable cyber peace in the IoE. Such an approach also accords with the “environmental metaphor for information law and policy” that has been helpful in other efforts (Reference FrischmannFrischmann, Madison, and Strandburg, 2014, 16).

It is important to recognize the polycentric nature of the IoE to ascertain the huge number of stakeholders – including users – that can and should have a say in contributing to legitimate governance. Indeed, such concerns over “legitimate” Internet governance have been present for decades, especially since the creation of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). Given the pushback against that organization as a relatively top-down artificial construct as compared to the more bottom-up Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), legitimacy in the IoE should be predicated to the extent possible locally through independent (and potentially air gapped) networks, Internet Service Providers (ISPs), and nested state, federal, and international law. To conceptualize such system, the literature on regime complexes might prove helpful, which is discussed next in the context of blockchain technology.

8.3 Is Blockchain the Answer to the IoE’s Woes?

Professor Ostrom argued that “[t]rust is the most important resource” (Escotet, 2010). Indeed, the end goal of any governance institution is arguably trust – how to build trust across users to attain a common goal, be it sustainable fishery management or securing the IoE. The GKC framework provides useful insights toward this end. But one technology could also help in this effort, namely blockchain, which, according to Goldman Sachs, could “change ‘everything’” (Reference LachanceLachance, 2016). Regardless of the question being asked, some argue that it is the answer to the uninitiated – namely, a blockchain cryptographic distributed ledger (Trust Machine, 2015). Its applications are widespread, from recording property deeds to securing medical devices. As such, its potential is being investigated by a huge range of organizations, including US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), IBM, Maersk, Disney, and Greece, the latter of which is seeking to leverage blockchain to help enhance social capital by helping to build trust around common governance challenges, such as land titling (Reference Casey and VignaCasey and Vigna, 2018). Examples similarly abound regarding how firms use blockchains to enhance cybersecurity. The technology could enable the Internet to become decentralized, pushing back against the type of closed platforms analyzed by Professor Johnathan Zittrain and others (Reference ZittrainZittrain, 2008). Already, a number of IoT developers are experimenting with the technology in their devices; indeed, according to one recent survey, blockchain adoption in the IoT industry doubled over the course of 2018 (Reference ZmudzinskiZmudzinski, 2019).

Yet formidable hurdles remain before blockchain technology can be effectively leveraged to help promote sustainable development, peace, and security in the IoE. No blockchain, for example, has yet scaled to the extent necessary to search the entire web. There are also concerns over hacking and integrity (such as when a single entity controls more than fifty percent of the processing power), including the fact that innovation is happening so quickly that defenders are put in a difficult position as they try to build resilience into their distributed systems (Reference VillasenorVillasenor, 2018). But the potential for progress demands further research, including how it could help promote a polycentric cyber peace in the burgeoning IoE.

8.4 Polycentric Implications

As Professor Cole has maintained, “those looking for normative guidance from Ostrom” and the relevant governance frameworks and design principles discussed herein are often left wanting (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 46). Similar to the big questions in the field of intellectual property, such as defining the optimal duration of a copyright, it stands to reason, then, that the Ostroms’ work might tell us relatively little about the goal of defining, and pursuing, cyber peace. An exception to the Ostroms’ desire to eschew normative suggestions, though, is polycentric governance, which builds from the notion of subsidiarity in which governance “is a ‘co-responsibility’ of units at central (or national), regional (subnational), and local levels” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 47).

For purposes of this study, the polycentric governance framework may be considered to be a multi-level, multi-purpose, multi-functional, and multi-sectoral model that has been championed by numerous scholars, including the Ostroms (Reference McGinnisMcginnis, 2011). It suggests that “a single governmental unit” is usually incapable of managing “global collective action problems” such as cyber-attacks (Reference OstromOstrom, 2009, 35). Instead, a polycentric approach recognizes that diverse organizations working at multiple scales can enhance “flexibility across issues and adaptability over time” (Reference Keohane and VictorKeohane and Victor, 2011, 15). Such an approach can help foster the emergence of a norm cascade improving the Security of Things (Reference Finnemore and SikkinkFinnemore and Sikkink, 1998, 895).

Not all polycentric systems are guaranteed to be successful. Disadvantages, for example, can include gridlock and a lack of defined hierarchy (Reference Keohane and VictorKeohane and Victor, 2011). Yet progress has been made on norm development, including cybersecurity due diligence, discussed later, which will help IoT manufacturers better fend off attacks against foreign nation states. Still, it is important to note that even the Ostroms’ commitment to polycentric governance “was contingent, context-specific, and focused on matching the scale of governance to the scale of operations appropriate for the particular production or provision problem under investigation” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 47). During field work in Indianapolis, IN, for example, the Ostroms found that, in fact, medium-sized police departments “outperformed both smaller (neighborhood) and larger (municipal-level) units” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 47). In the IoE context, as has been noted, the scale could not be greater with billions of people and devices interacting across myriad sectors, settings, and societies. The sheer complexity of such a system, along with the history of Internet governance to date, signals that there can be no single solution or governance forum to foster cyber peace in the IoE. Rather, polycentric principles gleaned from the GKC framework should be incorporated into novel efforts designed to glean the best governance practices across a range of devices, networks, and sectors. These should include creating clubs and industry councils of the kind that the GDPR is now encouraging to identify and spread cybersecurity best practices, leveraging new technologies such as blockchain to help build trust in this massively distributed system, and encouraging norm entrepreneurs like Microsoft and the State of California to experiment with new public–private partnerships informed by the sustainable development movement. Success will be difficult to ascertain as it cannot simply be the end of cyber attacks. Evaluation criteria are largely undefined in the GKC framework, as we have seen, which the community should take as a call to action, as is already happening by members of the Cybersecurity Tech Accord and the Trusted IoT Alliance.

Such efforts may be conceptualized further within the literature on the cyber regime complex. As interests, power, technology, and information diffuse and evolve over time within the IoE, comprehensive regimes are difficult to form. Once formed, they can be unstable. As a result, “rarely does a full-fledged international regime with a set of rules and practices come into being at one period of time and persist intact” (Reference Keohane and VictorKeohane and Victor, 2011, 9). According to Professor Oran Young, international regimes emerge as a result of “codifying informal rights and rules that have evolved over time through a process of converging expectations or tacit bargaining” (Reference Young and YoungYoung, 1997, 10). Consequently, regime complexes, as a form of bottom-up institution building, are becoming relatively more popular in both the climate and Internet governance contexts, which may have some benefits since negotiations for multilateral treaties could divert attention from more practical efforts to create flexible, loosely coupled regimes (Reference Keohane and VictorKeohane and Victor, 2011). An example of such a cyber regime complex may be found in a work by Professor Joseph S. Nye, Jr., which is reproduced in Figure 8.3.

Figure 8.3 Cyber regime complex map (Reference NyeNye, 2014, 8)

But there are also the costs of regime complexes to consider. In particular, such networks are susceptible to institutional fragmentation and gridlock. And there are moral considerations about such regime complexes. For example, in the context of climate change, these regimes omit nations that are not major emitters, such as the least developed nations that are the most at risk to the effects of a changing climate. Similar arguments could play out in the IoE context with some consumers only being able to access less secure devices due to jurisdictional difference that could impinge on their privacy. Consequently, the benefits of regime complexes must be critically analyzed. By identifying design rules for the architecture, interfaces, and integration protocols within the IoE, both governance scholars and policymakers may be able to develop novel research designs and interventions to help promote cyber peace.

8.5 Conclusion

As Cole has argued, “there are no institutional panaceas for resolving complex social dilemmas” (Reference Cole, Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgCole, 2014, 48). Never has this arguably been truer than when considering the emerging global digital ecosystem here called the IoE. Yet, we ignore the history of governance investigations at our peril, as we look ahead to twenty-first century global collective action problems such as promoting cyber peace in the IoE. Important questions remain about the utility of the Ostrom Design Principles, the IAD, and GKC frameworks in helping us govern the IoE. Even more questions persist about the normative goals in such an enterprise, for example, what cyber peace might look like and how we might be able to get there. That should not put off scholars interested in this endeavor. Rather, it should be seen as a call to action. The stakes could not be higher. Achieving a sustainable level of cybersecurity in the IoE demands novel methodologies, standards, and regimes. The Ostroms’ legacy helps to shine a light on the path toward cyber peace.

9.1 Introduction

This chapter describes our approach to combine the Contextual Integrity (CI) and Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) frameworks in order to gauge privacy expectations as governance. This GKC-CI approach helps us understand how and why different individuals and communities perceive and respond to information flows in very different ways. Using GKC-CI to understand consumers’ (sometimes incongruent) privacy expectations also provides deeper insights into the driving factors behind privacy norm evolution.

The CI framework (Reference NissenbaumNissenbaum, 2009) structures reasoning about the privacy implications of information flows. The appropriateness of information flows is defined in context, with respect to established norms in terms of their values and functions. Recent research has operationalized CI to capture users’ expectations in varied contexts (Reference Apthorpe, Shvartzshnaider, Mathur, Reisman and FeamsterApthorpe et al., 2018; Reference Shvartzshnaider, Tong, Wies, Kift, Nissenbaum, Subramanian and MittalShvartzshnaider et al., 2016), as well to analyze regulation (Reference SelbstSelbst, 2013), establish research ethics guidelines (Reference ZimmerZimmer, 2018), and conceptualize privacy within commons governance arrangements (Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and StrandburgSanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg, 2018).

The GKC framework examines patterns of interactions around knowledge resources within particular settings, labeled as action arenas, by identifying background contexts; resources, actors, and objectives as attributes; aspects of governance; and patterns and outcomes (Reference Frischmann, Madison and StrandburgFrischmann, Madison, and Strandburg, 2014). Governance is further analyzed by identifying strategies, norms, and rules-in-use through an institutional grammar (Reference Crawford and OstromCrawford and Ostrom, 1995). According to GKC, strategies are defined in terms of attributes, aims, and conditions; norms build on strategies through the incorporation of modal language; and rules provide further structure by embedding norms with consequences to sanction non-compliance. For example, a strategy can describe a digital personal assistant that uses audio recordings of users (attributes) in order to provide personalized advertisements (aim) when a user does not pay for an ad-free subscription (condition). If this information flow also included modal language, such as a hedge, like “may” and “could,” or a deontic, like “will” and “cannot,” it would be a norm. The addition of a consequence, such as a denial of service or financial cost, would make this example a rule. It is also notable that, from this perspective, there are differences between rules-on-the-books, which prescribe, and rules-in-use, which are applied.

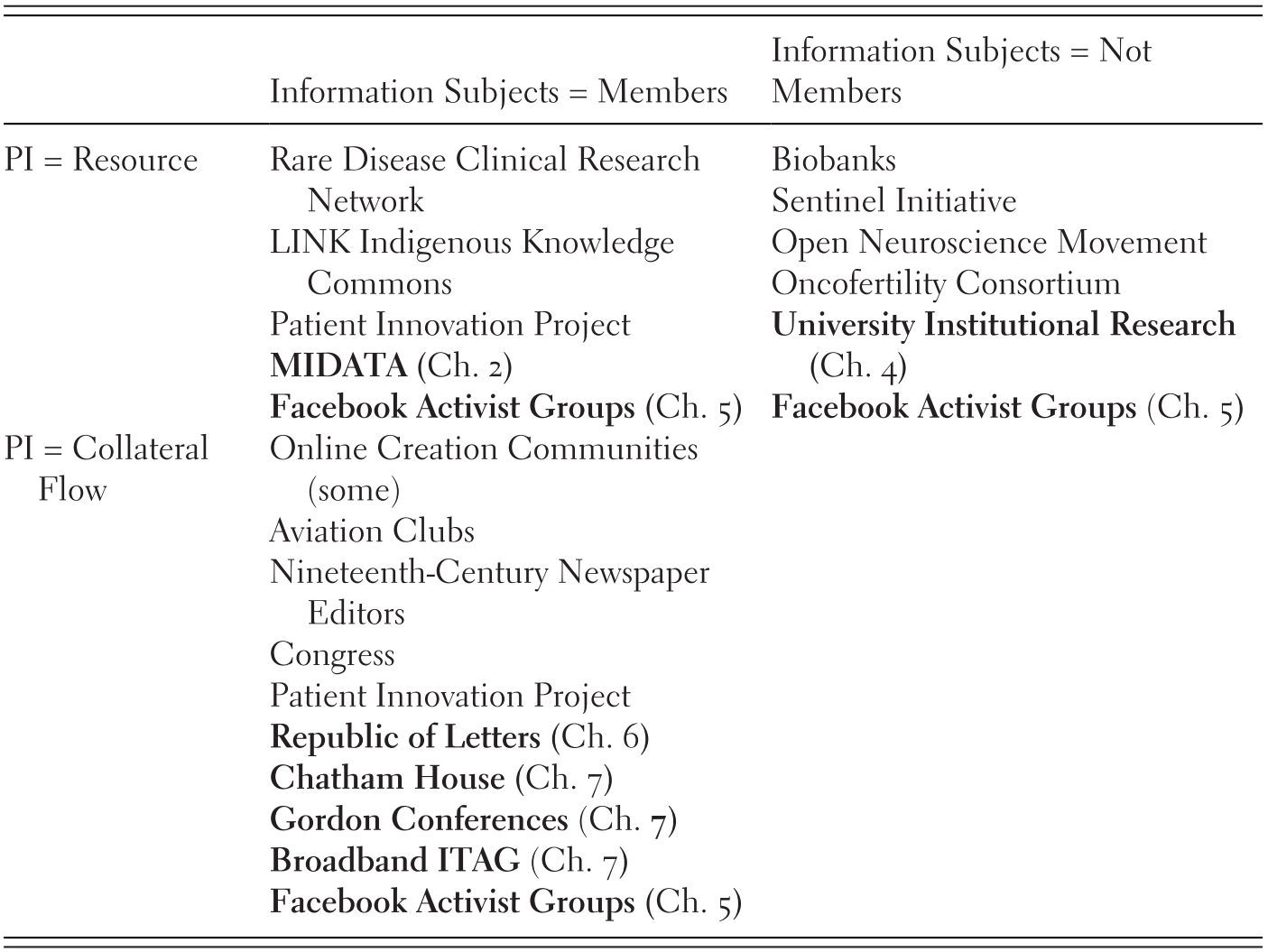

GKC and CI are complementary frameworks for understanding privacy as both governing institutions (Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and StrandburgSanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg, 2018) and appropriate flows of personal information, respectively. Within the GKC framework, as with the broader intellectual tradition of institutional analysis, an institutional grammar can be applied to deconstruct individual institutions (Reference Crawford and OstromCrawford and Ostrom, 1995). Table 9.1 illustrates the overlap between these frameworks and how each provides parameter specificity to the other. While the CI framework deconstructs information flows, the GKC framework considers governance structures and constraints regarding actors and their interactions with knowledge resources. Consider the digital personal assistant example from the previous paragraph. Under the institutional grammar (Reference Crawford and OstromCrawford and Ostrom, 1995), the digital personal assistant, audio recordings, and users are all considered “attributes.” The CI framework further divides these elements into sender, information type and subject parameters, respectively. Conversely, the CI framework uses the “transmission principle” parameter to articulate all constraints on information flows, while the GKC framework provides definitions of aims, conditions, modalities, and consequences.

Table 9.1 Conceptual overlap between CI and Institutional Grammar (GKC) parameters

In this work, we use the GKC and CI frameworks to understand the key aspects behind privacy norm formation and evolution. Specifically, we investigate divergences between privacy expectations and technological reality in the IoT domain. The consumer Internet of things (IoT) adds Internet-connectivity to familiar devices, such as toasters and televisions, resulting in data flows that do not align with existing user expectations about these products. This is further exacerbated by the introduction of new types of devices, such as digital personal assistants, for which relevant norms are only just emerging. We are still figuring out whether the technological practices enabled by these new devices align with or impact our social values. Studying techno-social change in the IoT context involves measuring what people expect of IoT device information flows as well as how these expectations and underlying social norms emerge and change. We want to design and govern technology in ways that adhere to people’s expectations of privacy and other important ethical considerations. To do so effectively, we need to understand how techno-social changes in the environment (context) can lead to subtle shifts in information flows. CI is a useful framework for identifying and evaluating such shifts as a gauge for GKC.

We conduct a multi-part survey to investigate the contextual integrity and governance of IoT devices that combines open-ended and structured questions about norm origins, expectations, and participatory social processes with Likert-scale vignette questions (Reference Apthorpe, Shvartzshnaider, Mathur, Reisman and FeamsterApthorpe et al., 2018). We then perform a comparative analysis of the results to explore how variations in GKC-CI parameters affect privacy strategies and expectations and to gauge the landscape of governing norms.

9.2 Research Design

In the first part of the survey, we asked respondents to list the devices they own and how they learn about the privacy properties of these devices (e.g., privacy policies, discussions with legal experts, online forums). We next presented the respondents with scenarios A through D, as described in Table 9.2, each scenario was followed by applied questions based on the GKC framework.

Table 9.2 Survey scenarios with corresponding aspects of the GKC framework

| # | Scenario | GKC Aspects |

|---|---|---|

| A | Imagine you’re at home watching TV while using your phone to shop for socks on Amazon. Your TV then displays an ad informing you about a great discount on socks at a Walmart close to your neighborhood. |

|

| B | You later hear from your neighbor that a similar thing happened to him. In his case, his wife posted on Facebook about their dream vacation. A few days later he noticed an ad as he was browsing the web from a local cruiser company. |

|

| C |

|

|

| D | You have an acquaintance who is a software engineer. They tell you that you shouldn’t be concerned. It’s considered a normal practice for companies to track the habits and activities of their users. This information is then typically sold to third parties. This is how you can get all of these free personalized services! |

|

Each scenario focused on different factors that previous research has identified as having an effect on users’ expectations and preferences (Reference Apthorpe, Shvartzshnaider, Mathur, Reisman and FeamsterApthorpe et al., 2018). Scenario A focused on third-party information sharing practices involving a smart TV that tracks viewing patterns and TV watching habits that are sold to an advertiser. Questions assessed the respondents’ specific concerns in this scenario as well as their anticipated reactions. We interpreted these reactions as indicators of respondents’ privacy expectations and beliefs as well as their understanding of information flows in context.

The remaining scenarios were built on Scenario A to explore different factors affecting privacy opinions and reactions. Scenario B introduced an additional, exogenous influence: a parallel, cross platform tracking incident that happened to someone else the respondent might know. Questions assessed how experiences with cross-device information flows and surrounding factors alter respondents’ expectations and resulting actions. This provides a sense of communities and contexts surrounding use, in order to support future institutionalization of information flows to better align with users’ values.

Scenario C focused on privacy policies and whether they mitigate privacy concerns. Specifically, we asked how often respondents read privacy policies and what they learn from them. We also queried whether the practice of information sharing with third parties potentially changes respondents’ behavior whether or not the data are anonymized. Finally, we asked whether the respondents would be willing to employ a workaround or disable information sharing for an additional charge – examples of rules-in-use contrasting sharply with rules-on-the-books that otherwise support information flows respondents may deem inappropriate.

Scenario D assessed how exogenous decision-makers influence privacy perceptions and subsequent behavior by providing respondents with an example of expert advice. Questions about this scenario addressed differences in perceptions between stakeholder groups as well as the legitimacy of expert actors in governance. While Scenario D specifically included a software engineer as the exemplar expert role, a parallel study has assessed perceptions of many additional expert actors (Shvartzshnaider, Sanfilippo, and Apthorpe, under review).

The second section of the survey tested how variations in CI and GKC parameters affect the perceived appropriateness of information flows. We designed this section by combining GKC parameters with an existing CI-based survey method for measuring privacy norms (Reference Apthorpe, Shvartzshnaider, Mathur, Reisman and FeamsterApthorpe, 2018).

We first selected GKC-CI parameters relevant to smart home device information collection. These parameters are listed in Table 9.3 and include a variety of timely privacy issues and real device practices.

Table 9.3 Smart home GKC-CI parameters selected for information flow survey questions

| Sender | Modality | Aim |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Subject & Type | Condition | |

|

| |

| Recipient | Consequence | |

|

|

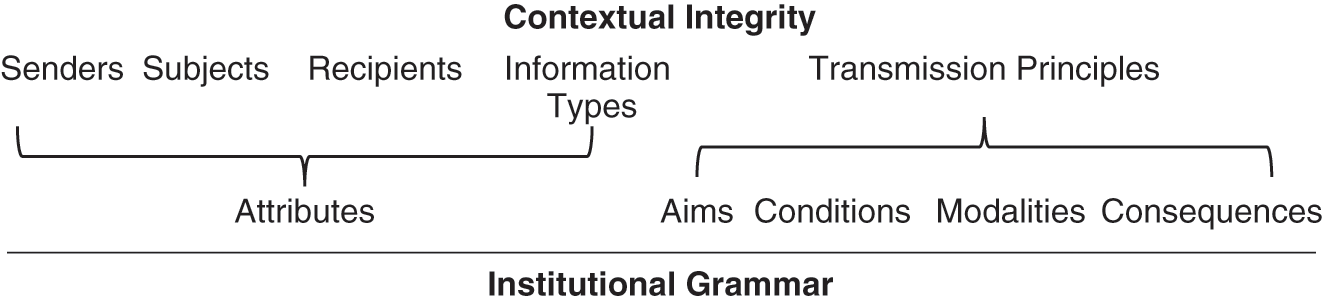

The questions in this section followed a parallel structure. Respondents were first presented with an information flow description containing a randomly selected combination of sender, subject, information type, recipient, and modal parameters (Figure 9.1). Respondents rated the appropriateness of this flow on a 6-point Likert scale from “very inappropriate” to “very appropriate.”

Figure 9.1 Example baseline information flow question

This baseline question was followed by a series of matrix-style multiple choice questions with one row for each condition, aim, and consequence parameter (Figure 9.2). Respondents were asked to indicate how each of these parameters would affect the appropriateness of the original information flow on a 5-point Likert scale from “much more appropriate” to “much less appropriate.”

Figure 9.2 Example question with varying condition parameters

This process was repeated three times for each survey participant. Each participant rated three sets of baseline flows with different subject/type/recipient/modal parameters and corresponding matrices for condition/aim/consequence parameters. Null parameters were included as controls for each category.

The survey concluded with a series of standard demographics questions, querying respondents’ age, gender, state of residence, education level, and English proficiency. Each of these questions had a “prefer not to disclose” option in case respondents were uncomfortable divulging this information.

We created the survey using Qualtrics. We conducted “cognitive interviews” to test survey before deployment via UserBob, an online usability testing platform. Five UserBob workers were asked to take the survey while recording their screen and providing audio feedback on their thought processes. These workers were paid $1 per minute, and all completed the survey in less than 10 minutes. While the UserBob responses were not included in the results analysis, they confirmed the expected survey length of less than 10 minutes and that the survey did not contain any issues that would inhibit respondents’ understanding.

We deployed the survey as a Human Intelligence Task (HIT) on Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT). The HIT was limited to AMT workers in the United States with a 90–100 percent HIT approval rating. We recruited 300 respondents and paid each $1 for completing the survey.

We began with 300 responses. We then removed 14 responses from individuals who provided incomprehensible answers or non-answers to the free-response questions. We also removed 2 responses from individuals who answered all matrix questions in the same column. This resulted in 284 total responses for analysis.

9.3 Governing Appropriate Flows of Personal Information from Consumer IoT

We analyze our survey results from the combined GKC-CI perspective. We use GKC framework to identify the background environment (specific context) of consumer IoT, attributes involved in the action arena of IoT information flows (including goals and objectives), governance rules within consumer IoT contexts, and various patterns and outcomes, including the perceived cost and benefits of IoT information flows. We also use the CI framework with the institutional grammar parameters (aims, conditions, consequences, modalities) as transmission principles to understand what specific aspects of governance have the most significant impact on respondent perceptions.

9.3.1 Background Environment

Smart devices are pervasive in Americans’ lives and homes. We interact with a wide range of these supposedly smart systems all the time, whether we recognize and consent to them or not, from Automated License Plate Readers (ALPR) technologies tracking drivers’ locations (Reference JohJoh, 2016) to Disney World’s MagicBand system (Reference Borkowski, Sandrick, Wagila, Goller, Chen and ZhaoBorkowski et al., 2016) to Alexa in dorm rooms (Reference Manikonda, Deotale and KambhampatiManikonda et al., 2018). These devices, which are part of a larger digital networked environment, collect massive amounts of data that surreptitiously capture human behaviors and support overt sociotechnical interactions in public and private spaces.

It is notable that there are very different scales of use and applications of smart devices, with many deployed publicly without public input. In contrast, smart devices in individuals’ homes are most often configured by the users themselves with appropriate use negotiated within households. Notable exceptions include the controversial and well-publicized implementations of smart locks and systems in rental housing (e.g., Reference Geeng and RoesnerGeeng and Roesner, 2019) and uses of IoT to surveil victims by perpetrators of domestic violence (Reference Tanczer, Neira, Parkin, Patel and DanezisTanczer et al., 2018). These consumer IoT devices have wildly different patterns of interactions and governance. They are operated under complex arrangements of legal obligations, cultural conditions, and social norms without clear insight into how to apply these formal and informal constraints.

It is thus important to establish applicable norms and evaluate rules-in-use to support good governance of consumer IoT moving forward. Understanding interactions where users have some control of institutional arrangements involving their devices is helpful toward this end. We therefore focus on consumers’ everyday use of smart devices, primarily smartphones, wearables, and in-home smart devices. It is our objective to understand both how users would like information flows associated with these devices to be governed and how their privacy perceptions are formed.

The background context for personal and in-home IoT device use extends beyond individual interactions with smart devices. It includes aggregation of information flows from devices and interactions between them, discussion about the relevant normative values surrounding device use, and governance of information flows. There are distinct challenges in establishing norms, given that there is no default governance for data generated, as knowledge resources, or predictable patterns of information to help form user expectations.

Our survey respondents documented the devices they owned, which aligned with recent consumer surveys of IoT prevalence (e.g., Reference Kumar, Shen, Case, Garg, Alperovich, Kuznetsov, Gupta and DurumericKumar et al., 2019). About 75 percent of respondents reported owning more than one smart device, with 64 percent owning a smart TV and 55 percent owning a Digital Personal Assistant (such as an Amazon Echo, Google Home, or Apple HomePod). Smartwatches were also very popular. A small percentage of respondents owned smart lightbulbs or other Internet-connected appliances.

As these devices become increasingly popular and interconnected, the contexts in which they are used are increasingly complex and fraught with value tensions, making it important to further study user preferences in order to develop appropriate governance. For example, digital personal assistants don’t clearly replace any previous analogous devices or systems. They therefore lack pre-existing norms or underlying values about appropriateness to guide use. In contrast, smart televisions are obviously analogous to traditional televisions and are thereby used in ways largely guided by existing norms. These existing norms have often been shaped by entrenched values but do not always apply to emerging information flows from and to new smart features. The resulting tensions can be resolved by identifying relevant values and establishing appropriate governing institutions around IoT information flows. To do so, it is first important to understand the relevant factors (attributes) so as to clarify how, when, and for what purpose changes in information flows governance are and are not appropriate.

9.3.2 Attributes

9.3.2.1 Resources

Resources in the IoT context include both (1) the data generated by devices and (2) knowledge about information flows and governance. The latter also includes characteristics of these devices, including necessary supporting technologies and personal information relevant to the IoT action arena.

The modern home includes a range of devices and appliances with Internet-connectivity. Some of these devices are Internet-connected versions of existing appliances, for example, refrigerators, TVs, thermostats, lightbulbs. Other devices, such as digital assistants (e.g., Amazon Echo and Google Home), are new. These devices produce knowledge by generating and consuming information flows. For example, a smart thermostat uses environmental sensors to collect information about home temperature and communicates this information to cloud servers for remote control and monitoring functionality. Similar information flows across devices are causing the IoT ecosystem to evolve beyond the established social norms. For example, now refrigerators order food, toasters tweet, and personal health monitors detect sleeping and exercise routines. This rapid change in the extent and content of information flows about in-home activities leads to a mismatch between users’ expectations and the IoT status quo. Furthermore, mismatches extend beyond privacy to features, as some new “smart” functions are introduced for novelty sake, rather than consumer preferences, such as kitchen appliances that are connected to social media.

Our survey respondents’ comments reveal discrepancies between users’ privacy perceptions/preferences and how IoT devices are actually used. This provides further insight into the attributes of data resources within this context by illustrating what is considered to be appropriate. For example, some respondents noted that even though they have smart TVs, they disconnect them from the Internet to limit communication between devices. Generally, our survey results highlight the range of confusion about how smart devices work and what information flows they send.

A few respondents implied that they were only learning about IoT cross-device communications through the scenarios described in our survey, describing their surprise (e.g., “How they already know that. How did it get from my phone to the tv? That seems very fishy”) or in some cases absolute disbelief (“I see no connection between what I’m doing on the phone and a random TV ad”) that such a thing was possible. One respondent specifically summarized this confusion amidst common experiences with new technologies:

At first, you are concerned. The lightning fast speed at which Google hits you in the heads [sic] for an item you were considering buying makes you believe they are spying on you. They aren’t spying, because spying implies watching you without your permission, but in using the service you give them complete permission to use any data you put into search queries, posts, etc, to connect you to items you are shopping for, even if it is just to look around.

Social media consumers do not understand that they are NOT the customer. They are the product. The customer is the numerous businesses that pay the platform (Google, Facebook, etc) various rates to get their product in front of customers most likely to pay. Radio did this long before Cable TV who did this long before Social Media companies. It’s a practice as old as steam.

This quotation highlights perceived deception about information collection practices by popular online platforms and IoT devices. Users of IoT devices are shaping their expectations and practices amidst a lack of transparency about privacy and problematic notions of informed consent (e.g., Reference Okoyomon, Samarin, Wijesekera, Elazari Bar On, Vallina-Rodriguez, Reyes and EgelmanOkoyomon et al., 2019). This respondent also touches on the inextricable links between the two knowledge resources; when users have poor, confusing, or limited explanations of information flows, they fail to understand that they are a resource and that their data is a product.

As Figure 9.3 illustrates, respondents learn about IoT information flows and privacy from a variety of different sources. Online forums represent the most prevalent source of privacy information, yet only just over 30 percent of respondents turn to online forums of IoT users with privacy questions. Privacy policies and discussions with friends and family were also common sources of privacy information, but even these were only consulted by 28 percent and 25 percent of respondents, respectively. Respondents turned to technical and legal experts for privacy information even less frequently, with only 9 percent and 3 percent of respondents reporting these sources, respectively. Overall, there was no single source of privacy information consulted by a majority of respondents.

Figure 9.3 Where respondents learn about the privacy implications of IoT devices

9.3.2.2 Community Members

Community members, through the lens of the GKC framework, include those who participate and have roles within the action arena, often as users, contributors, participants, and decision-makers. The action arena also includes a variety of additional actors who shape these participants’ and users’ expectations and preferences, including lawyers and privacy scholars; technologists, including engineers and developers; corporate social media campaigns; anonymous discussants in online forums; and friends and family, which we examine in a related study (Shvartzshnaider, Sanfilippo, and Apthorpe, under review). It is important to consider who is impacted, who has a say in governance, and how the general public is impacted. In this context, community members include IoT device owners, developers, and users, as well as users’ family, friends, and neighbors in an increasingly connected world.

While the respondents who depend on online communities and forums for privacy information are a small subset, those communities represent an important source of IoT governance in use. User-generated workarounds and privacy discussions are meaningful for understanding and establishing appropriate information flows. Users are thus the community-of-interest in this context, and those who responded to our survey reflect the diversity of users. The respondents were 62 percent male and 37 percent female with an average age of 34.5 years. 53 percent of the respondents had a Bachelor’s degree or higher. 38 percent of respondents self-reported annual incomes of <$40,000, 43 percent reported incomes of <$80,000, 8 percent reported incomes of <$100,000, and 10 percent reported income of >$100,000. We have not established clear demographic indicators for the overall community of IoT users, in this sense, beyond ownership and a skew toward a younger population. However, it is also possible that tech savviness is overrepresented among users.

9.3.2.3 Goals and Objectives

Goals and objectives, associated with particular stakeholders, are grounded in history, context, and values. It is important to identify the specific obstacles and challenges that governance seeks to overcome, as well as the underlying values it seeks to institutionalize.

In our studies, the respondents identified multiple governance objectives and dilemmas associated with information flows to and from IoT devices, including control over data collection and use, third parties, and autonomy in decision-making. Interests among respondents were split between those who valued cross-device information flows and those who felt increased interoperability and/or communication between devices was problematic. Additionally, there were a few respondents who agreed with some of the perceived interests of device manufacturers that value monetization of user data; these respondents appreciated their ability to utilize “free services” in exchange for behavioral data collection. Furthermore, there are additional tensions between the objectives of manufacturers and developers and the interests of users, as evidenced by the split in trust in the expertise of a technical expert in judging appropriateness of information flows. These results show fragmentation in perception of both governance and acceptance of the status quo for information flows around IoT devices.

9.3.3 Governance

Through the lens of the GKC framework, including the institutional grammar, we gain insight into different aspects of governance. We can capture how the main decision-making actors, individual institutions, and the norms governing individual information flows emerge and change over time, as well as how these norms might be enforced. Results also indicate that privacy, as appropriate flows of personal information, governs interactions with and uses of IoT devices. For example, we see evidence that anonymization, as a condition modifying the information type and its association with a specific subject within an information flow, does not serve as meaningful governance from the perspective of respondents. Fifty-five percent of respondents stated that they would not change their behavior, or support cross-device communication, just because data was anonymized. It is not immediately clear, from responses to that question alone, what leads to divergence on this interpretation of anonymization or any other perceptions about specific information flows. However, it echoes theorization about CI that incomplete transmission principles are not helpful in understanding information flows (e.g., Reference Bhatia and BreauxBhatia and Breaux, 2018), extending this idea to governance; the condition of anonymity is not a stand-alone transmission principle.

This aligns with our approach combining the GKC and CI frameworks to gauge the explicit and implicit norms that govern information flows within a given context. The CI framework captures norms using five essential parameters of information flows. Four of the parameters capture the actors and information type involved in an information flow. The fifth parameter, transmission principle, constrains information flows. The transmission principle serves as a bridging link between the CI and GKC frameworks. Figure 9.4 shows the average score for perceived appropriateness for an information flow without qualifying it with the transmission principle. We remind the reader that the respondents were first presented with information flow descriptions using sender, subject, information type, recipient, and modal parameters. They rated the appropriateness of these flows on a 6-point Likert scale from “very inappropriate” (-2) to “very appropriate” (+2).

Figure 9.4 Average perceptions of information flows by parameter

Figure 9.5 The impact of specific parameters in changing respondent perceptions of information flows.

For the GKC framework questions in the first part of the survey, 73 percent of respondents reported that they would change their behaviors in response to third-party sharing. Specific actions they would take are illustrated in Figure 9.6. Figure 9.4 shows that respondents view a “manufacturer” recipient less negatively than a generic third party. Additionally, not stating a recipient all together has a lesser negative effect on information flow acceptability than a generic “third party” recipient. We can speculate that when the recipient is omitted, the respondents mentally substitute a recipient that fits their internal privacy model, as shown in previous research (Reference Martin and NissenbaumMartin and Nissenbaum, 2016).

Figure 9.6 User actions in response to third-party sharing scenarios

We further gauge the effect on user perceptions of aims, conditions, modalities, and consequences as components of transmission principles. Figure 9.5 illustrates changes in average perceptions based on the addition of specific aims, conditions, and consequences to the description of an information flow. We see that stating a condition (such as asking for consent, upon notification or keeping the data anonymous) has a positive effect on the perception of appropriateness. Conversely, we see that not stating an aim correlates with positive perception, while the respondents seemed on average neutral towards “for developing new features” and “for academic research” aims, they show negative attitude towards the “for advertising purposes” aim. When it comes to consequences, the results show that the respondents view not stating a consequence as equal, on average, to when the information “is necessary for the device to function properly.” However, respondents viewed information flows with the consequence “to personalize content” slightly positively, while viewing information flows with the consequence of “[generating] summary statistics” correlates with slightly negative perception.

Respondents also identified a number of additional approaches that they might take in order to better control flows of their personal information and details of their behaviors between devices. In addition to browsing anonymously and disconnecting their smart TV from the Internet, various respondents suggested:

“Use a VPN”

“Wouldn’t buy the TV in the first place”

“It’s just getting worse and worse. I’ll almost certainly return it.”

“Research and see if there is a way to not have my info collected.”

“Be much more careful about my browsing/viewing habits.”

“Circumvent the tracking”

“Try to find a way to circumvent it without paying”

“Sell it and get a plain TV”

“Block access to my information”

“Delete cookies”

“Disable features”

When they perceived information flows to be inappropriate, many respondents favored rules-in-use that would circumvent inadequate exogenous governance. While many respondents favored opportunities to opt out of inappropriate flows, a small sub-population developed their own approaches to enact their privacy preferences as additional layers of governance in use. Often these work-arounds subverted or obfuscated default information flows.

9.3.3.1 Rules-in-Use and Privacy Policies

Few respondents found the rules-on-books described in privacy policies to be useful for understanding information flows associated with IoT devices. Many respondents described how they found privacy policies lengthy and confusing. For example, when asked what they learn from reading privacy policies, one respondent explained:

That they [sic] hard to read! Seriously though, they are tough to interpret. I know they try and protect some of my information, but also share a bunch. If I want to use their services, I have to live that [sic].

One of the 62 respondents who reported that they read privacy policies “always” or “most of the time” further elaborated:

I’ve learned from privacy policies that a lot of times these company [sic] are taking possession of the data they collect from our habits. They have the rights to use the information as they pleased, assuming the service we’re using from them is advertised as ‘free’ I’ve learned that sometimes they reserve the right to call it their property now because we had agreed to use their service in exchange for the various data they collect.

The information users learn from reading a privacy policy can undermine their trust in the governance imposed by IoT device manufacturers. The above comment also touches on issues of data ownership and rights to impact or control information flows. Privacy policies define rules-on-the-books about these issues, which some respondents perceive to be imposed governance. However, as noted by another respondent, the policies do not apply consistently to all devices or device manufacturers:

That companies can be pretty loose with data; that some sell data; that others don’t go into specifics about how your data is protected; and there are some that genuinely seem to care about privacy.

This comment emphasizes an important point. For some respondents, practices prescribed in privacy policies affect how they perceive each respective company. In cases where privacy policy governance of information flows aligns with social norms, companies are perceived to care about privacy. Respondents also identify these companies as more trustworthy. In contrast, privacy policies that are vague about information flows or describe information flows that respondents perceive to be egregious or excessive, such as selling user data to many third parties, indicate to respondents that associated companies do not care about user privacy.

Relative to these inappropriate and non-user centered information flows and policies, respondents also described rules-in-use and work-arounds that emerged in order to compensate for undesirable rules-on-the-books. Over 80 percent of respondents indicated that they would pursue work-arounds, with many pursuing alternate strategies even if it took an hour to configure (31 percent) or regardless of difficulty (32 percent).

A few respondents recognized that privacy policies sometimes offer ways to minimize or evade tracking, such as outlining opportunities to opt out, as well as defining the consequences of those choices. When asked “What do you learn from privacy policies?,” one respondent elaborated:

Occasionally, there are ways to minimize tracking. Some of the ways the data is used. What things are needed for an app or device.

In this sense, privacy policies disclose and justify information flows, often discouraging users from opting-out through institutionalized mechanisms, such as options to disable recommendations or location services, by highlighting the features they enable or the consequences of being left out. However, despite institutionalized mechanisms to evade tracking, opt out options are sometimes insufficient to protect privacy (Reference MartinMartin, 2012). Furthermore, many respondents don’t actually read privacy policies and therefore may not be aware of them. Thus, individuals also develop their own approaches and share them informally among friends and online communities, as shown in Figure 9.1.

Through the lens of the GKC framework, privacy policies serve as a source for rules-on-the-books. These rules govern the flow of information into and out of IoT companies. From respondents’ comments, we see that privacy policies play an important role in shaping their expectations for better for worse. On one side, the respondents turn to privacy policies because they want to learn “what [companies] do and how they may use information they receive.” On the other side, respondents echoed the general public frustration of not being able to “to learn anything because [privacy policies] are purposefully wordy and difficult to understand.” Companies that outline clear information governance policy help inform users’ expectations about their practices, while those companies that offer ambiguous, lengthy, hard to understand policies force users to rely on their existing (mostly negative) perceptions of company practices and/or turn to other sources (family, experts) for information.

Finally, the respondents discuss several options for dealing with the gap between rules-on-the-books and their expectations. First, they could adjust their expectations (“these smart devices know too much about me,” “be more careful about what I do searches on”). They could also find legal ways to disable practices that do not align with their expectations, such as paying to remove ads or changing settings (“I trust them but I still don’t like it and want to disable”). In addition, they could opt out from the service completely (“Sell it and get a plain TV”).

9.3.4 Patterns and Outcomes

Our survey reveals a significant fragmentation within the community of IoT users relative to current governance practices, indicating irresolution in the action arena. As we piece together data on who IoT users are and how they are shaping appropriate flows of personal information from and between their smart devices, certain patterns and outcomes become evident. Table 9.4 illustrates how respondents’ preferences about third party sharing, professed concerns about privacy, and device ownership shape their average perceptions of governance outcomes around IoT. We assessed the extent to which respondents embraced technology based on the number of devices they own.

Table 9.4 divides the respondents of our survey into subcommunites based on the opinions of various IoT practices elicited from the first part of the survey. Some respondents largely have embraced IoT technologyFootnote 4 and are not concerned about privacy issues.Footnote 5 Others, while embracing the technology, are concerned about privacy issues. Concerns about third party sharing or a lack of embrace of smart technology yield very different opinions, on average. We cluster these subcommunities into three groups, in order to gauge their perceptions.

When gauging the respondents’ perceptions, we note that those who are unconcerned about the privacy implications of cross platform sharing, regardless of other values associated with information governance, have on average favorable views of information flows. Additionally, those respondents who express general concern about the privacy implications, but are not concerned about third party sharing, have similar perceptions on average. These subpopulations of our respondents are the most likely to belong to group 1, who perceive current governance of IoT information flows to be positive, on average. In contrast, those who are concerned about privacy and either don’t embrace smart technologies or express concerns about third party sharing are most likely to belong to group 3, who are slightly dissatisfied with current governance outcomes on average. Finally, group 2 is generally concerned about privacy but embraces smart devices with average perceptions slightly above neutral.

Table 9.4 Average perceptions of information flow appropriateness gauged by respondent subpopulations. For each subcommunity we calculate the number of respondents and the average perception score across information flows including consequence, condition, and aim.

| Embrace Tech (own >2 devices) | Don’t embrace tech | Concerned about third party sharing | Not concerned about third party sharing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconcerned |

|

|

|

|

| Concerned |

|

|

|

|

We now highlight the open-ended comments from respondents belonging to each group, that put their opinions in context, in an effort to better understand fragmentation and what underlying beliefs and preferences lead to divergent normative patterns. While individual comments are not representative, they illuminate individuals’ rationales underlying perceptions associated with groups.Footnote 6

9.3.4.1 Group 1: Positive Perceptions