The lexicon of Punjabi includes loanwords from Arabic, English, Hindi-Urdu, Persian, Sanskrit, Turkish, and other contact languages. Most loanwords are fully integrated into the native phonology but some recent English loanwords (related to science and technology) are yet to be adapted. The word Punjabi itself is a combination of two Persian words, /pəɲ ʤ/ پَنج ‘five’ and /ab/ آب ‘water’, which literally means ‘the land of five rivers’(Shackle Reference Shackle, Cardona and Jain2003). Punjabi is written in two scripts: Gurmukhi – mainly used in India – and Shahmukhi – a modified Perso-Arabic script frequently employed by Punjabi speakers in Pakistan.

The many dialects of Punjabi are broadly classified into two groups: Eastern and Western. The Eastern dialects are primarily spoken in the Indian state of Punjab, whereas the Western dialects cover the area of Punjab in Pakistan (Singh Reference Singh1971); however, the distribution of speakers and varieties is more complicated (Shackle Reference Shackle1979). In 1947, during the partition of India and Pakistan, a large number of Punjabi speakers migrated from India to Pakistan and settled around Lahore, Sahiwal, Faisalabad, and Gujranwala. Similarly, Punjabi speakers from the Punjab state of Pakistan moved to India. The term Lahnda (also Lahanda, Lahandi, or Lahndi, meaning Western) has been used as an umbrella term covering North-Western (Hindko, Peshawari), North-Eastern (Pothwari/Pothohari, Awankari), and Southern (Siraiki or Multani) dialects that differ from the ‘Punjabi proper’ spoken in the Central and Eastern Punjab (Grierson Reference Grierson1916, Bhardwaj Reference Bhardwaj2016). The status of Lahnda has been questioned, and the boundary between these varieties and Punjabi is unclear (Shackle Reference Shackle1979, Reference Shackle, Brown and Ogilvie2006, Bhatia Reference Bhatia, Brown and Ogilvie2006, Bhardwaj Reference Bhardwaj2016). Siraiki, that was once classified as a variety of Lahnda, is now considered a separate language, characterized by a five-way laryngeal contrast (/p pʰ b bʱ ɓ/) (Shackle Reference Shackle1977, Reference Shackle, Cardona and Jain2003). Dialects of Hindko also differ phonologically from each other, and from other Lahnda languages (Shackle Reference Shackle, Brown and Ogilvie2006).

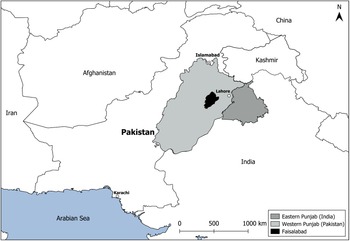

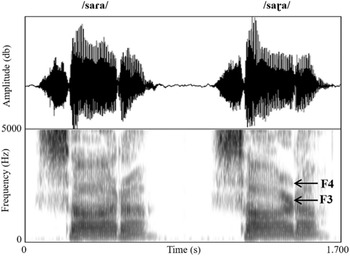

This paper describes the variety of Punjabi known as Lyallpuri, spoken in the urban areas of Faisalabad (formerly Lyallpur), as demonstrated by a 30-year-old male native speaker (the first author). The consultant was born and raised in a Punjabi-speaking environment in Faisalabad (Figure 1), and Lyallpuri is his first language. He is literate in Punjabi (Shahmukhi script) and has used Punjabi as his primary language for most of his life. The consultant also speaks Urdu and English, and has lived outside Pakistan as an adult, but regularly communicates with other Punjabi speakers. All analyses are based on recordings of this speaker. Lyallpuri forms part of the chain of Western dialects of Punjabi, and closely resembles varieties of Punjabi spoken in Lahore, Sahiwal, and Gujranwala, although the differences between these have not been systematically examined.

Figure 1 Location of Eastern and Western Punjab. The Lyallpuri variety of Punjabi is spoken in Faisalabad (Western Punjab), Pakistan.

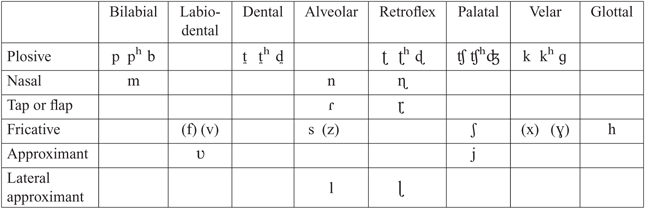

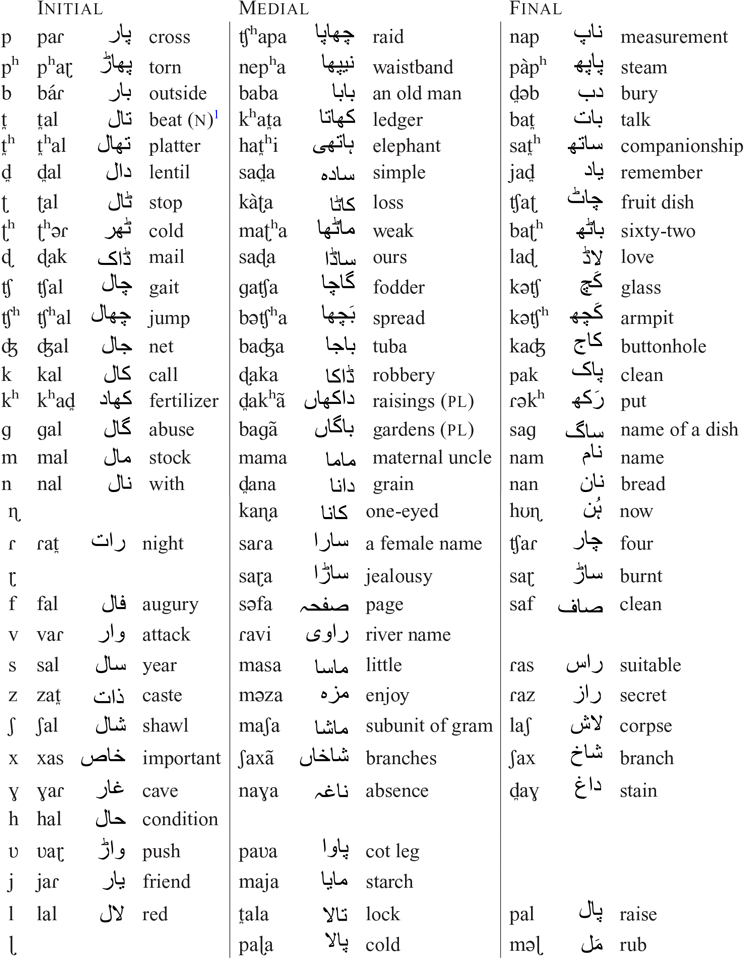

Consonants

Lyllapuri Punjabi uses 32 consonants, including five fricatives found only in loanwords (in parentheses). Most consonants are contrastive in word-initial, word-medial, and word-final positions. The consonants set in parentheses in the Consonants Table are contrastive in our consultant’s speech but they are generally absent from the speech of Lyallpuri speakers residing in rural areas.

Obstruents

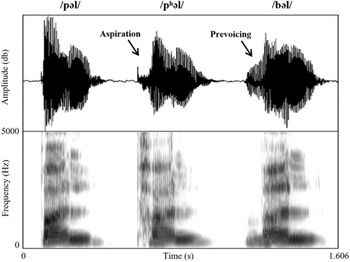

Lyallpuri Punjabi has a three-way laryngeal contrast in plosives (voiceless unaspirated, voiceless aspirated, and voiced unaspirated) at five places of articulation (labial, dental, retroflex, palatal and velar). The three-way laryngeal contrast is illustrated in a series of labial plosives in Figure 2. Plosives are contrastive in all word positions.

Figure 2 Waveforms and spectrograms of word-initial labial plosives, illustrating the 3-way laryngeal contrast. Left-to-right: /pəl/ پَل ‘moment’, /pʰəl/ پَھل ‘fruit’, and /bəl/ بَل’curl’. Aspirated release (/pʰ/) and prevoiced (/b/) intervals are indicated.

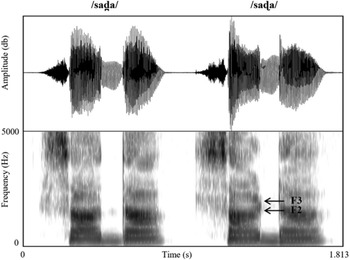

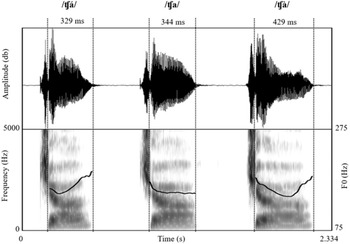

There is a three-way coronal contrast in plosives: dental, retroflex, and palatal (e.g. /t̪ ʈ ʧ/). /ʧʧʰʤ/ have been characterized as palatal (Arun Reference Arun1961, Bhatia Reference Bhatia1993) andpalatoalveolar (Dulai & Koul 1980). Retroflex plosives are characterized by shorter closure duration, shorter release burst (or VOT) duration, and greater convergence of second and third formants from preceding vowels, compared to their dental counterparts (Hussain et al. Reference Hussain, Proctor, Harvey and Demuth2017, Hussain Reference Hussain2018). Retroflex and dental plosives produced in intervocalic contexts are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Waveforms and spectrograms of word-medial voiced dental and retroflex plosives. Left-to-right: sad̪a/ سادہ ‘simple’, /saɖa/ ساڈا ‘ours’.

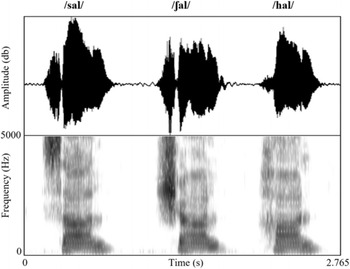

Eight fricatives are contrastive in the idiolect of our consultant: /f v s z ʃ x ɣ h/. Labiodental /f v/, voiced alveolar /z/, and velar fricatives /x ɣ/ are only found in loanwords from Arabic, English, Persian, and Urdu (Dulai Reference Dulai1989, Bhatia Reference Bhatia1993, Bukhari Reference Bukhari2008, Bhardwaj Reference Bhardwaj2016), and not all speakers maintain all contrasts. /h/ can occur word-initially but not word-medially and finally. Fricatives /s ʃ h/, found in the native lexicon, are illustrated in word-initial position in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Waveforms and spectrograms illustrating word-initial fricative contrasts. Left-to-right: /sal/ سال’year’, /ʃal/ شال’shawl’, and /hal/ حال’condition’.

Nasals

Lyallpuri Punjabi contrasts nasals at three places of articulation: labial /m/, dental /n/, and retroflex /ɳ/. Labial and dental nasals can occur in all word positions, whereas retroflex /ɳ/ only occurs word-medially and word-finally. Palatal and velar nasals occur as allophones of /n/ and are found in homorganic clusters with palatal and velar plosives (see details in the ‘Consonant phonotactics’ section below).

Approximants

There is a four-way liquid contrast in Lyallpuri Punjabi: /ɾ/ ‒ /l/ ‒/ɽ/ ‒ /ɭ/. Rhotics are prototypically realized as taps in the speech of our consultant. /ɾ/ and /l/ can occur in all word positions, but the retroflex tap /ɽ/ and lateral /ɭ/ contrast with alveolar /ɾ/ and /l/ only word-medially and word-finally. Figure 5 illustrates the contrast between alveolar /ɾ/ and retroflex /ɽ/ taps. The retroflex tap /ɽ/ is characterized by earlier lowering of third and fourth formants into a shorter, less attenuated interval of occlusion. Labial /ʋ/ and palatal /j/ approximants are contrastive word-initially and word-medially, but not word-finally.

Figure 5 Waveforms and spectrograms illustrating word-medial rhotic contrasts: /saɾa/ سارہ’a female name’ (left) and /saɽa/ ساڑا ‘jealousy’ (right).

Geminates

Nineteen consonants of Lyallpuri Punjabi have contrastive geminate forms: /p pʰb t̪ t̪ʰ d̪ ʈʈʰɖ k kʰɡʧʧʰʤ s m n l/. Geminate consonants are always preceded by central vowels (/ɪ ə ʊ/). Geminate plosives are characterized by longer closure duration compared to singletons; duration varies with place of articulation but, overall, mean total duration of geminate plosives is approximately 40% greater than singleton equivalents (Hussain Reference Hussain2015). Contrastive singleton and geminate plosives are illustrated in word-medial contexts in Figure 6.

Figure 6 Waveforms and spectrograms of voiceless unaspirated singleton /t̪/ in/pət̪a/ پَتا’address’ (top) and voiceless unaspirated geminate /t̪ː/ in/pət̪ːa/ پَتّا ‘leaf’ (bottom).

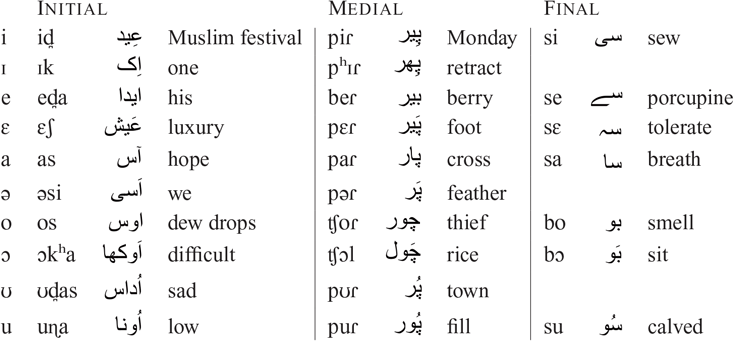

Vowels

Lyallpuri Punjabi contrasts ten oral vowels in closed syllables. Oral vowels can be categorized as central, /ɪ ə ʊ/ and peripheral, /i e ɛ a o ɔ u/. Peripheral vowels are typically longer than central vowels, and only peripheral vowels occur in all word positions. Peripheral vowels may be analyzed as bimoraic, and central vowels as monomoraic (see section ‘Syllable structure’ below). Figure 7 illustrates the distribution of word-medial vowels according to mean first and second formant frequencies (Table 1).

Figure 7 Acoustic distribution of word-medial oral vowels. Mean values (Bark) of first (vertical axis) and second (horizontal axis) formants at vowel midpoints. Average of five tokens, elicited using words in center column of vowel contrasts table.

Table 1 Mean first and second formant frequencies for Punjabi vowels produced in word-medial position, in Hz and Bark

In addition to oral vowels, Lyallpuri Punjabi has a contrastive set of nasal vowels. All seven peripheral oral vowels contrast with their nasal counterparts (Bhatia Reference Bhatia1993, Shackle Reference Shackle, Cardona and Jain2003), but central vowels do not show nasal vs. oral opposition. Oral/nasal vowel contrasts are illustrated in (1) (adapted from Shackle Reference Shackle, Cardona and Jain2003: 588).

(1) Oral vs. nasal vowels in Lyallpuri Punjabi

Lyallpuri Punjabi uses thirteen contrastive oral diphthongs. /ɛɔ/ do not occur as a first or second member of any diphthongs, and central vowels /ɪ ə ʊ/ do not occur as a second member of any diphthongs. /ɪ ʊ/ also have constraints as a first member of the diphthongs. There are no diphthongs with nasal vowels either as a first or a second member. Monosyllabic words contrasted by diphthongs are illustrated in (2).

(2) Lyallpuri Punjabi diphthongs

Prosodic features

Syllable structure

In Lyallpuri Punjabi, syllables consist maximally of one onset consonant and two coda consonants (C)V(V)(C)(C). The vast majority of words are monosyllabic or disyllabic. Peripheral vowels are bimoraic, and the central vowels are monomoraic. There is a word minimality constraint which requires that lexical items must contain at least two moras of structure (i.e. they are a foot). Representative examples of possible syllable types are presented in (3).

(3) Lyallpuri Punjabi syllable types

Consonant phonotactics

Word-initial clusters are not found in the native Punjabi lexicon. Words with final consonant clusters are rare, but can be found in Arabic, English, Persian, and Urdu loanwords, with the structures illustrated in (4). The realization of final consonant clusters depends on speech rate, speaker literacy, and bilingualism (Gill & Gleason Reference Gill and Gleason1962).

(4) Word-final clusters

(a) Fricative + plosive

(b) Rhotic + plosive

Plosives can occur as the first or second member of heterorganic word-medial consonant sequences. If the first consonant is a plosive, the second consonant can be a plosive, liquid or nasal. Word-medial plosive (voiced) + plosive (voiced) sequences occur across morpheme boundaries, seen in (5a) below. In heterorganic nasal + plosive sequences, the plosive is always voiceless in roots, as in (5d), but at morpheme boundaries, nasal + voiced plosive sequences are permitted (e.g. /ʧʊm.d̪a/ ‘kiss + present singular masculine marker’). Heterorganic word-medial consonant sequences are exemplified in (5).Footnote 4

(5) Heterorganic word-medial consonant sequences

(a) Plosive + plosive

(b) Plosive + liquid

(c) Plosive + nasal

(d) Nasal + plosive

(e) Fricative + plosive

Homorganic word-medial consonant sequences are also permitted in Lyallpuri Punjabi, most commonly nasals + plosives, illustrated in (6).

(6) Homorganic word-medial consonant sequences: nasal + plosive

Stress and tone

Stress is not contrastive in Lyallpuri Punjabi. All words have at least one stressed syllable. Stress assignment is sensitive to syllable weight, which is determined by the length of the nucleus (central vowels are short; peripheral vowels are long) and the structure of the rime. Three categories of syllable weight are necessary to account for the distribution of stress: light (monomoraic: (C)V, e.g. /pə.ʤa پَجا’fifty’,Footnote 5 heavy (bimoraic: (C)V, e.g. /ʤa/ جا ‘Go! (imp)’, and superheavy (trimoraic: (C)VC, e.g. /mas/ ماس’skin’; or (C)VCC, e.g. /ʧəɾs/ چَرس ‘weed’). In disyllabic words, the leftmost superheavy syllable is stressed, shown in (7a) below. If there is no superheavy syllable, then the penultimate syllable is stressed. In trisyllabic words as in (7b), stress is always placed on the penultimate or antepenultimate syllable, but not on the final syllable.Footnote 6

(7) Patterns of stress assignment, illustrated on disyllabic and trisyllabic words with differing syllable weights: light (L: short-central vowel, no coda), heavy (H: long-peripheral vowel only, or short-central vowel + coda), and super-heavy (S: long-peripheral vowel + coda)

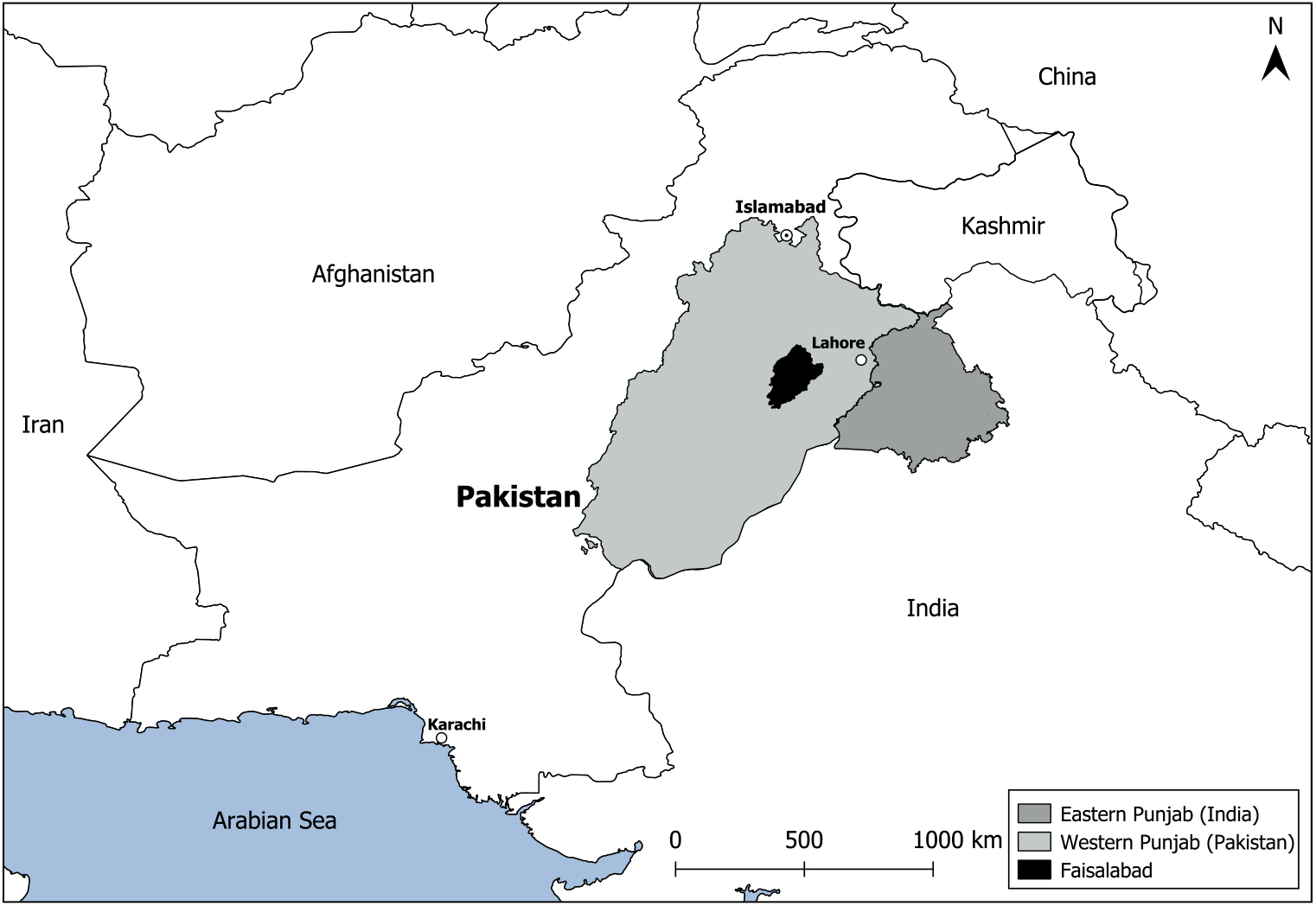

A notable feature of Lyallpuri Punjabi, as in other dialects, is the development of three contrastive tones: high (ˊ), mid (not generally marked) and low (ˋ) (Bahl Reference Bahl1957, Reference Bahl and Sebeok1969, Gill Reference Gill1960, Baart Reference Baart, Caspers, Chen, Heeren, Pacilly, Schiller and van Zanten2014). Tones always align with the stressed syllable (Bailey Reference Bailey1914, Dhillon Reference Dhillon2010), and can occur on both open and closed syllables. Tonal syllables are always stressed, but not vice versa. Monosyllabic and disyllabic words contrasting only in tones are illustrated in (8). Pitch tracks characterizing the three tones are presented in Figure 8.

(8) Three-way tonal contrast in Lyallpuri Punjabi

Mid tone is the default tone and occurs on vowels where there is no tone specification at the phonetic level (Bhatia Reference Bhatia1975). In the high tone, pitch is raised at the end of the vowel (Figure 9). Low tone generally has a falling-rising contour (Campbell Reference Campbell and Tolstaya1981), but typically achieves a lower f0 target than the other two tones. The three tones are also characterized by temporal differences (Gill Reference Gill1960): low tones have the longest duration, and high tones the shortest (Figure 9).

Figure 8 Waveforms and spectrograms of /ʧá/ چا ‘tea’ (left), /ʧa/چاہ ‘enthusiasm’ (middle) and /ʧà/ چا ‘peek’ (right), bearing high, mid, and low tones, respectively. F0 has been superimposed on each spectrogram (solid line) to illustrate pitch trajectories for each tone (left y-axis: frequency range of spectrogram; right y-axis: f0 range).

Figure 9 Mean pitch trajectories of high (/ʧá/ [ʧa425] چا ‘tea’), mid (/ʧa/ [ʧa32]چاہ ‘enthusiasm’), and low (/ʧà/ [ʧa513] چا ‘peek’ tones (average of five repetitions of each word). F0 was calculated at 10 ms intervals throughout each vowel /a/. Ribbons around mean pitch tracks indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Transcription of the North Wind and the Sun

This passage was translated from English to Lyallpuri Punjabi. Only high ( ́) and low ( ̀) tones are marked.

Phonemic transcription

ʃʊmal d̪i həʋa t̪e suɾəʤ ʋɪʧ ɾəpʰːəɽ peja si pəi kon bót̪a t̪akət̪ʋəɾ e

t̪e feɾɪk mʊsafəɾ aja jine͂ kəmbəl d̪i bʊkːəl maɾi hoi si

ona͂ ne ʃəɾt̪ la ləi pəi ʤéɽa pɛ́la͂ mʊsafəɾd̪a kəmbəl lʊʋa d̪eʋe o bót̪a t̪akət̪ʋəɾ hoʋe ɡa

feɾ ʃʊmal d̪i həʋa puɾa zoɾ la ke ʧəlːi pəɾ o ʤɪnːa͂ zoɾ la ke ʧəld̪i si mʊsafəɾ əpna kəmbəl ona͂ i kəs ke bʊkːəl maɾ lɛ̃d̪a si

axəɾ ʃʊmal d̪i həʋa ne haɾ ke bəs kit̪i

feɾ suɾəʤ ɡəɾmi nal ʧəmkeja t̪e mʊsafəɾ ne ʧʰet̪i nal əpna kəmbəl lá d̪ɪt̪ːa

t̪e ɛ̃ʤ ʃʊmal d̪i həʋa nu͂ mənəna peja pəi d̪ona͂ ʋɪʧːo͂ suɾəʤ bót̪a t̪akət̪ʋəɾ e

Orthographic version (Shahmukhi script)

The following translation of the passage is written in Shahmukhi script (right-to-left). It should be noted that voiced aspirates and word-medial and word-final /h/ that have been lost in the speech of Lyallpuri Punjabi speakers, are still written in the Shahmukhi script.

شُمال دی ہَوا تے سُورج وِچ رَپّھڑ پیا سی پَئی کون بوہتا طاقتور اے۔

تے فیر اِک مُسافر آیا جینیں کَمبل دی بُکّل ماری ہوئی سی

اوناں نے شرط لا لئی پئی جیہڑا پہلاں مُسافر دا کَمبل لُوا دیوے او بوہتا طاقتور ہووے گا

فیر شُمال دی ہوا پُورا زور لا کے چلّی، پر او جِنّاں زور لا کے چلدی سی مُسافر اپنا کَمبل اوناں ای کَس کے بُکّل مار لیندا سی۔

آخر شُمال دی ہَوا نے ہار کے بس کیتی۔

فیر سُورج گرمی نال چمکیا تے مُسافر نے چھیتی نال اپنا کَمبل لا دِتّا۔

تے اینج شُمال دی ہَوا نوں مَننا پیا پَئی دوناں وِچّوں سُورج بوہتا طاقتوراے۔

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the editor, Amalia Arvaniti, and two anonymous reviewers for their input and helpful suggestions. We are also grateful to the members of the Child Language Lab at Macquarie University, particularly Ivan Yuen. This research was supported by an Endeavour Postgraduate Scholarship (Australian Government, Department of Education and Training) to the first author, and by Australian Research Council Award DE150100318.