Reproduction is a biological and political project.

— Zakiya Luna (Reference Luna2020, 13)Legal pluralism is a defining feature of US federalism, and in few ways is this as apparent as the unequal legal landscape of reproductive rights. While the US Supreme Court may set a floor of equal protection under which states may not fall, each state interprets and approaches the floor differently, making meaningful comparisons across multiple jurisdictions incredibly difficult. Using methods from the field of public health law offers a compelling way to study multifaceted socio-legal issues across multiple jurisdictions even in the face of federal-state pluralism. To illustrate the benefits of this method and offer ways in which to adapt it to socio-legal studies, this article offers the State Reproductive Autonomy Index, a measure of reproductive autonomy, defined as “having the power to decide about and control matters associated with contraceptive use, pregnancy, and childbearing” (Upadhyay et al. Reference Upadhyay, Dworkin, Weitz and Foster2014). Taking a reproductive justice lens that focuses on the right to have and to raise children as much as the right to prevent or terminate pregnancy (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Silliman et al. Reference Silliman, Gerber Fried, Ross and Gutierrez2004 J. Nash Reference Nash2021; SisterSong, n.d.), the State Reproductive Autonomy Index uses seventy-five variables from each of the fifty states, including abortion and contraception rights, rights related to pregnancy and parenthood, birth choice, and socioeconomic status. Studying these interlocking policies exposes the ways in which rights are constrained both from state intervention (for example, making abortion and contraception inaccessible) and from a lack of state intervention (for example, allowing discrimination in foster care and adoption), complicating our understanding of what it means to have a right by considering the ways in which some rights rest upon others or intertwine in ways that make it impossible to compare the policy and rights landscape without a broad focus.

While abortion tends to dominate the political discussion, it is important to keep one eye looking beyond traditional reproductive rights parameters to capture the full scope of constraints—through law and policy—on all reproductive choices (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Luna Reference Luna2020). Understanding the forms that these constraints take requires engaging with scholarship on legal pluralism (Merry Reference Merry1988), with the work of reproductive justice scholars and activists, and with public health work on the legal determinants of health (Coggon Reference Coggon2020). Several measures of reproductive autonomy already exist, but their focus is narrowly tailored to exploring contraceptive autonomy (Senderowicz Reference Senderowicz2020), the attitudes of college students (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Fawson, Siegel, Jones and Stone2018), women at family planning and abortion facilities (Upadhyay et al. Reference Upadhyay, Dworkin, Weitz and Foster2014), and reproductive autonomy as it relates to policy (Vedam et al. Reference Vedam, Stoll, Marian, Declercq, Cramer, Cheyney, Fisher, Butt, Yang and Kennedy2018; Cramer Reference Cramer2021). A more encompassing measure—the Local Reproductive Freedom Index—evaluates reproductive health, rights, and justice policies in fifty US cities, highlighting the need and possibility for a socio-legal approach to understanding how reproductive choices are shaped by legal forces (National Institute for Reproductive Health 2019). This State Reproductive Autonomy Index does not seek to replace local-level measures like the Local Reproductive Freedom Index, as ground-level understanding is invaluable to advocates and policy makers. What this measure offers is a way to supplement local and regional indices with broader socio-legal data that can be used by scholars, advocates, and policy makers to contextualize policy debates. Additionally, it provides a template for studying socio-legal issues that span the boundaries of multiple disciplines and jurisdictions and are constrained by different types of laws and policy.

The State Reproductive Autonomy Index offers three main contributions for scholars and policy makers. First, it integrates the reproductive justice framework with the mainstream academic socio-legal and public health law discourse. Second, it leads to a deeper understanding of the connections between the lived experience of rights and how legally plural environments shape those experiences through different uses of social and economic policies. Third, it shows the need for further engagement between the legal, political, and social science literatures and public health law methods. By taking an approach that considers the social determinants of health and looks to the “upstream” determinants of unequal access, or the “causes of causes” that precipitate legal and health disparities (Braveman and Gottlieb Reference Braveman and Gottlieb2014), we can make visible the invisible force of the law governing many choices related to reproduction.

LEGAL MAPPING: A TRANSDISCIPLINARY METHOD FOR A MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD

Reproductive justice scholars have repeatedly demonstrated the utility of an integrative approach to understanding reproductive autonomy that includes the lived experience of policy, law, and economics (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Davis Reference Davis2019; SisterSong, n.d). Likewise, the “transdisciplinary model” of public health law research provides a way to quantify this integrated approach without losing the crucial focus on the lived experience (Burris et al. Reference Burris, Marice Ashe, Penn and Larkin2016). There is incredible potential to unlock by integrating public health law methods into socio-legal studies in ways that are appropriate to our field. Along with methodological benefits of transdisciplinary research, similar questions about rights and law have emerged within the literature of public health, birthrights, and the social determinants of health. These questions have formed the basis for the selection of variables in this index.

This project uses a transdisciplinary method—the “true integration of theories, methods, and tools” from across disciplinary realms (Burris et al. Reference Burris, Marice Ashe, Penn and Larkin2016, n.p.)—adopted from public health law studies that are situated between legal mapping and legal epidemiology. Pulling from public health law methods, this method explores the role of three types of laws known as the three I’s: infrastructural (those that shape institutions and the environment), interventionist (specifically targeted toward policies and outcomes), and incidental (background conditions that are not intentionally related). While this type of method is suited to other transdisciplinary, highly charged, and seemingly intractable problems, such as police violence and prison recidivism, reproductive autonomy is my starting point because the laws are so varied along the three I’s that success in measuring this concept will certainly offer pathways to look at other politically entrenched legal issues. For instance, in a study of police violence, one could explore the connection between police education requirements, recruitment, and salaries (infrastructural), the legality of chokeholds and other methods of restraint (interventionist), and the community-level rate of incarceration, poverty, and racism (incidental), among other variables, in order to provide a wide-angle lens on the scope, sources, and prevention strategies for violence.

The reason behind constructing the State Reproductive Autonomy Index is that the public health and socio-legal literatures do not appear to be speaking to each other, despite their clear links, and the literatures are not in conversation with the wider socio-legal work on rights. Bringing the literatures together offers a substantial contribution to theory and methods in socio-legal studies because it engages legal epidemiology’s work to measure “law’s strong determinative effects … on our social, governmental, commercial and physical environments” (Coggon Reference Coggon2020, n.p.). Sandra Levitsky (Reference Levitsky2013) stresses the need to study “law’s effects on social policy because state policy shapes our social lives” (34). Weaving interrelated legal categories together is crucial because “evaluation at the intersection of law and social science can yield meaningful insights into how broadly, deeply, and effectively policy makers efforts translate into public policy that achieves its objectives” (Tremper et al. Reference Tremper, Thomas and Wagenaar2010). Charles Tremper et al. (Reference Tremper, Thomas and Wagenaar2010) also note “producing the most accurate measures requires close attention to relationships among law and from different sources…and at different levels” (246). These different legal sources converge to shape the legal environment. This article illustrates a way to directly examine the law and its power as the underlying element in constructing health disparities through the lens of reproductive health and justice by using legal mapping to compare laws across multiple jurisdictions.

As partisan polarization takes on more explicit legal battles, law’s role as a social force calls us to explore the law in new and inclusive ways. As Michael McCann (Reference McCann2006, 21) notes, “legal constructs shape our very capacity to imagine social or political possibilities.” This capacity of law as meaning making is widely understood (Marshall and Barclay Reference Marshall and Barclay2003; McCann Reference McCann2006; Levitsky Reference Levitsky2013). Anna Maria Marshall and Scott Barclay (2003, 618) contend that “law colonizes everyday existence” because it shapes what we think of as legitimate, acceptable, or possible. In legally plural environments, this creates systems where cultural or social practices may take precedence over law on the books, making rights in practice different than rights on paper (Merry Reference Merry1988). Yet, as Sandra Levitsky (Reference Levitsky2013, 34) notes, even those rights based in law are often subject to litigation, which, in some senses, renders them in a constant state of flux—in reproductive autonomy, this can be seen in a sustained campaign of litigation over abortion and access to contraception. When law and rights are so different or inconstant across the fifty states, especially laws relating to bodily autonomy, we must ask whether we are living not only in legally plural environments but also in different socio-legal realities. As the United States continues to grow more polarized along partisan lines that target explicitly political issues (Rhodes and Vayo Reference Rhodes and Vayo2019), socio-legal scholars should be poised to expose the ways in which widespread partisan polarization may be leading to these different legal realities across state jurisdictions, calling into question the existence of rights at all. Legal mapping will provide a vital tool for this project.

WHY REPRODUCTIVE AUTONOMY?

This project is indebted to the immense work that reproductive justice scholars have done to expose the role that law, society, and politics play in procreation and their insistence that “reproductive decision-making is about the lived experience of individuals, including, for many persons, their drive to possess reproductive autonomy” (Ross and Solinger 2018, 7; emphasis in the original). Reproductive autonomy is more than pro-choice rights discourse. As Jael Silliman and colleagues (2004) note, the very idea of a choice is premised upon autonomy—namely, sovereignty over one’s own body; the awareness of, and access to, alternatives; and the freedom from coercion. Studying autonomy exposes the ways in which law and policy shape what choices we have and what we think of as choices at all, filtering our “choices” in ways that are not captured by reproductive rights discourse. Autonomy is, on the one hand, freedom from state interference in reproductive choices (for example, midwife licensure), but, on the other hand, it also relies on a certain amount of intervention in order to protect freedom (for example, enforcing safety zones around abortion clinics). In their article, Kathryn Norsworthy, Margaret McLaren, and Laura Waterfield (Reference Norsworthy, McLaren, Waterfield and Chrisler2012, 67) explain “women’s reproductive choices must be framed within a broader social context that is characterized by gender discrimination and unequal access to basic health resources.” Unpacking what autonomy looks like complicates rights discourse because it exposes the ways in which interlocking laws and policies shape widespread access to a right, while also calling for nuance in discerning when intervention is empowering or disempowering (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991, Reference Crenshaw2012).

The choice of whether, when, and how to procreate or establish one’s preferred family is fundamental to personal liberty. Understanding how law and politics shape these choices furthers our understanding of how law shapes all of our lives and choices. When talking about reproduction, law’s constraints on women’s full autonomy are normalized to the point of invisibility, making it seem as though people’s choices are personal and a matter of preference when, in reality, they are shaped and constrained by policy and legal parameters (Norsworthy, McClaren, and Waterfield Reference Norsworthy, McLaren, Waterfield and Chrisler2012; E. Nash Reference Nash2019). Using legal mapping to study reproductive autonomy allows us to look at a set of laws that govern one group differently than others, illustrating law’s pluralism (intentional or not) in terms of both state-federalism issues and in terms of treating different genders differently. Feminist scholars like Catherine MacKinnon (Reference MacKinnon2005) have pointed out the need to study politics and law in a way that is explicitly conscious and critical of a system where men write laws that apply to women in ways that do not apply to other men, and reproduction is an obvious example of this pattern. Perhaps the most succinct explanation for the need to study reproductive autonomy through a multilayered socio-legal lens that focuses on rights and power comes from the Black feminists who founded the Combahee River Collective (1977, n.p.): “[O]ur particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives.”

These interlocking systems of oppression and the way in which they are synthesized by and through law make it impossible to get an accurate understanding of reproductive autonomy by only focusing on one element of the system or on one element of autonomy, indicating the need for a sweeping measurement like the one presented in this article. Kimberle Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1991, Reference Crenshaw2012) further exposes the need for a holistic study of the race, class, and gender dynamics that produce intersections of legal marginalization within these interlocking systems. These intersectional barriers push us to understand that, even in a single state or political culture, law affects differently situated groups in ways that cannot be unpacked into neat categories, and, in some cases, membership in one group (for example, race, gender, sexuality) can increase the risk of legal, social, or political violence (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991). Rights look different depending on where you are as well as on who you are.

The State Reproductive Autonomy Index is necessary in itself because, while legal scholars have long contended that “there are fewer and fewer ‘zones of immunity’ from law” for all people (Friedman Reference Friedman1985, 22), women of childbearing age in the United States live their lives “in the shadow of the law” in a way that other groups do not (Currie Reference Currie2009, 9). Women’s reproductive choices are policed through society and law—from the social phenomenon of strangers telling pregnant people they should not drink coffee (Fox, Nicolson, and Heffernan Reference Fox, Nicolson, Heffernan and Jackson2009; Cramer Reference Cramer2015), to a federal court ordering a Florida mother to have a cesarean (Gluck Reference Gluck2014), to strangers asking women about their procreation plans. Once we expand our understanding of reproductive autonomy to include choices about pregnancy or raising children in a safe and healthy environment, as reproductive justice scholar-activists do (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Davis Reference Davis2019; Luna Reference Luna2020; J. Nash Reference Nash2021; SisterSong, n.d.), we complicate measures that attempt to quantify reproductive autonomy. But any measure that does so will be a more accurate representation of autonomy as it is experienced.

Reproductive justice contends that reproductive autonomy encompasses as much the right to have children and raise those children as it does the right not to have them (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Davis Reference Davis2019; SisterSong, n.d.). Created by a group of Black women as an activist movement in response to finding themselves left out of the mainstream feminist movement’s discourse on reproductive rights (Silliman et al. Reference Silliman, Gerber Fried, Ross and Gutierrez2004; J. Nash Reference Nash2021) and sidelined by President Hilary Clinton’s health-care plan (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Luna Reference Luna2020; SisterSong, n.d.), the reproductive justice framework has been challenging the individual and exclusionary focus on liberal rights to prevent pregnancy that white liberal feminism promotes, at times to the detriment of non-dominant groups that do not experience the conditions necessary for a choice to be a truly free and fair choice between competing alternatives (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Chrisler Reference Chrisler and Chrisler2012). It has thus created a more inclusive understanding of how we can and should talk about reproductive politics generally and about reproductive autonomy specifically.

Reproductive justice scholarship provides a framework for conceptualizing the ways in which law, politics, and society shape people’sFootnote 1 constellation of choices throughout their reproductive years. Yet reproductive justice has been largely absent from mainstream social science and legal studies literature in favor of a reproductive rights discourse partly because of the ubiquity of liberal rights discourse and because it is more pragmatic to draw connections among specific, closely related policies. The State Reproductive Autonomy Index uses a reproductive justice frame and suggests that reproductive justice should be the dominant narrative through which scholars and advocates discuss reproductive politics (whether rights, law, or policy) despite (or because) it complicates rights discourse in a way that reflects the varied lived experiences of different groups. The State Reproductive Autonomy Index also exposes the contours of legal pluralism and uses legal epidemiology methods to measure reproductive autonomy in a way that is compatible with socio-legal scholarship, methods, and discourse.

Reproductive justice recognizes that reproductive struggles are essentially about power rather than choice itself (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017, 11), and this is where a measure of reproductive autonomy becomes difficult. Some illustrative examples of policies where state power is targeted against autonomy can expose law’s constraints on women’s bodies and rights. In Texas, for instance, a law makes it illegal to disconnect a pregnant woman from life support even if her living will stipulates that she does not wish to remain on life support even while pregnant (Fernandez Reference Fernandez2014). Another is the case of Jennifer Goodall who, in 2014, refused her hospital’s requirement to have a repeat cesarean. Attempting to coerce her compliance, the hospital threatened to call child services, and, when that did not work, they went to a Florida judge who court-ordered Goodall to have a cesarean—major abdominal surgery that is not without risks—over her expressed consent (Jacobsen Reference Jacobsen2014).

Creating an even more pressing legal conundrum, Wisconsin allowed the state to appoint a lawyer as guardian to a fetus without the consent of its mother, Alicia Beltran, who disclosed a past history of pill addiction (National Advocates for Pregnant Women 2019). Reported by her doctor to the Department of Health Services, Beltran was arrested when she was fourteen-weeks pregnant; she appeared in court and was denied counsel herself but was told that her fetus had been assigned a lawyer and that it was on this authority that she was sentenced to a mandatory detention in a treatment center. Further, this case proceeded with no testimony from medical witnesses, and the treatment facility was suited to neither the type of drug treatment being sought nor prenatal care (Graham Reference Graham2014; National Advocates for Pregnant Women 2019). This example brings up different questions about rights and state intervention. If a legal spokesperson can be appointed for a fetus with no input from the person carrying the fetus who is capable of making a decision, the question becomes who decides when and under what circumstances this is appropriate? When this is done either without or against medical evidence, it is an even more invasive use of state power and calls into question what having a right to bodily autonomy means. The fact that some pregnant people, particularly Black people and Latinas, are subject to more social construction as bad or even dangerous mothers only increases the risks to reproductive autonomy in the form of state intervention (Norsworthy, McClaren, and Waterfield Reference Norsworthy, McLaren, Waterfield and Chrisler2012; Oaks Reference Oaks2015; Davis Reference Davis2019; J. Nash Reference Nash2021).

Studying reproductive autonomy shows that even laws once meant as rights to protect women against domestic violence can be turned on their heads to punish women, showcasing a legal-political, rather than a health-safety, power dynamic. Thirty-eight states have “feticide” laws on the books, many of which may be deployed with the discretion of a physician or law enforcement (National Abortion Rights Action League 2019). Christine Taylor of Iowa was charged with “attempted feticide” after the pregnant mother of two fell down the stairs, completely by accident. Bei Bei Shuai, who attempted suicide by swallowing rat poison, was charged by the state of Indiana with feticide when she survived but the fetus did not (Graham Reference Graham2014). Feticide laws can also be used to criminalize miscarriage and stillbirth. Georgia law allows up to thirty years in prison for a miscarriage (Naftulin Reference Naftulin2019). Michele Goodwin’s (2016, S19) research exposes the results of the criminalization of pregnancy, outlining the ways in which pregnancy is the catalyst for punishing women who “but for their pregnancies … would not have been prosecuted for doing something wrong.” These stories represent only a fraction of the scope of reproductive constraints and offer a reason why reproductive autonomy should be a fundamental point of legal, social, and political studies about rights, health and wellness, and access to justice.

These examples are often framed as an attack on the 1973 case Roe v. Wade, however, understanding the individual anecdotes as connected through state commitment for or against reproductive autonomy can expose a much larger pattern of coercive power that extends beyond pregnancy through birth and into parenting and can be used in other areas to study how states police intimate areas of our lives (Center for Reproductive Rights 2020; Guttmacher Institute 2020a).Footnote 2 Though this can be applied to other policies, especially the carceral state and broader welfare policies (Briggs Reference Briggs2017), reproductive autonomy is my starting point because simply by existing and being a certain age women and people with uteri are governed by laws and policies that treat them as potential procreators, which is a burden men that do not share.

While the anecdotes above could produce their own papers on the legal and justice issues that arise from state power and the racial disparities in pregnancy policing (Roberts Reference Roberts2017), understanding the state’s commitment (or lack thereof) to reproductive autonomy helps explain the varied conditions under which these kinds of constraints on reproductive autonomy can arise and the backdrop against which policy makers would have to push to undo them. Unpacking the ubiquity of these constraints will be a useful tool in fully exposing how law is complicit in (de)constructing reproductive autonomy. As McCann (Reference McCann2014, 251) notes, “classical liberal and neoliberal rights define mostly procedural rights that place selective limitations on arbitrary violence by discrete actors but do not limit routinized systemic violence … and require few positive mandates for social equality and redistribution of power.” The State Reproductive Autonomy Index includes variables to measure this systemic violence as well as its interconnectedness, particularly through legal pluralism in a federalist system.

MEASURING REPRODUCTIVE AUTONOMY

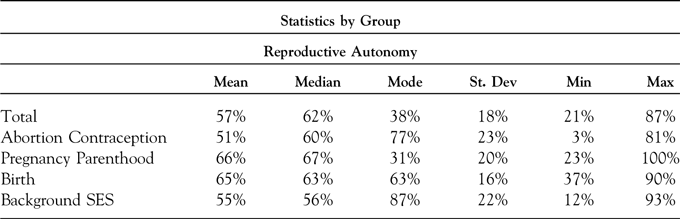

To develop the State Reproductive Autonomy Index, I categorized data for each of the fifty states based on seventy-five different variables. I tracked variables relating to abortion and contraception access (twenty-six variables), pregnancy and parenthood (thirteen variables), birth choice (fifteen variables), and background socioeconomic status data (twenty-one variables). For a full list of variables broken up by category, see Appendix 1. Variables are grouped together by subcategories to offer the ways in which not only to compare reproductive autonomy generally but also to expose areas where incidental and infrastructural laws may be invisibly shaping reproductive autonomy. For example, seeing a state in the middle range overall could indicate a state with high abortion rights but low socioeconomic rights. While an aggregate measure would signal moderate reproductive autonomy, looking at the subcategories would show the ways in which some laws make other legal rights difficult to access. Public health law favors these methods because federal, state, and municipal laws all shape which public health measures are possible and affect the success of public health policy. Looking at reproductive autonomy through public health law methods allows us to conceptualize what is both a public health and legal issue in a new way. Other legal public health problems like gun violence, police violence, vaccine equity, disability justice, or environmental law could all benefit from this type of methodology, which explores interlocking laws and policies.

Variables were selected from across multiple literatures that would benefit from engaging with each other and using the three I’s model. Considering how many laws and policies shape reproductive autonomy, it was important to choose those laws that could be both meaningfully compared across jurisdictions and that exemplify law’s presence in tipping the scales for or against autonomy, leading to a public health law/legal epidemiology model. Drawing these laws together in the manner of legal epidemiology helps capture how infrastructural laws (such as maternity care deserts or for-profit hospitals), interventionist laws (such as laws banning abortion or insurance funding for in vitro fertilization [IVF]), and incidental laws (such as welfare laws) all work together to form a reasonable expectation of reproductive autonomy. Using this strategy means exploring the conditions that shape institutions and environments (infrastructural), laws specifically targeted toward, or related to, the subject at hand (interventionist), and background conditions that shape practical access to legal rights (incidental).

Laws that were binary are coded one or zero (for example, is there a state law banning self-medicated abortion: a zero is for no; a one is for yes). When there are different degrees of severity in a law, the law is coded out of one, as a one represents a complete restriction. For example, in waiting periods for abortions, the highest level is seventy-two hours (coded as a one), the next is forty-eight hours (0.75), then twenty-four hours (0.5), then eighteen hours (0.25), and, finally, no waiting period (coded as zero). This is done rather than weighting the categories to make a comparison without judging which variables may be more important in a given space or for a given person.

Abortion and Contraception Variables

This category was the most obvious starting point because the choice to become/not become pregnant is a clear measure of reproductive autonomy. Abortion and contraception variables capture the ability of people to access reproductive services such as birth control and abortion by examining the multilevel issues of geographic, legal, and economic access to these services. Variables in this category include laws on abortion as well as barriers to access in terms of physicality (for example, no abortion facilities) and economics (for example, Medicaid policies), with the notion that, if you cannot access a right, you do not have it. These variables were chosen based on the legal and political literature surrounding reproductive rights. Abortion and contraception variables include infrastructural laws like the percentage of women who live in an abortion care desert because many women lack transportation (Pruitt and Vanegas Reference Pruitt and Vanegas2015; E. Nash Reference Nash2019; National Abortion Rights Action League 2019; Guttmacher 2020a). They also include whether there are clinic safety laws in place to protect those who seek access, likewise, whether there is a birth control desert, which are areas in which birth control is inacessible or unavailable (Planned Parenthood Federation of America 2012; National Abortion Rights Action League 2019; Guttmacher 2020a). In addition, these variables include interventionist laws like whether there is a law that requires emergency room physicians to dispense emergency contraceptives (such as Plan B, commonly known as “the morning after pill”) because emergency contraception needs to be given within a short time frame in order for it to work, and a doctor who refuses to give it is denying a patient their right to reproductive autonomy (World Health Organization 2018; Guttmacher 2020a; Kaiser Family Foundation 2020). It is within these variables that we first see the difficulty in discerning how autonomy looks as it relates to the state because, in some ways, state intervention prevents accessing rights (that is, making something illegal) and, in other ways, it guarantees it (that is, mandating that pharmacists provide prescriptions). Further, this category helps illustrate the role that the three I’s play in shaping whether we can reasonably expect practical access to a right that exists on the books.

Abortion and contraception variables also include whether state law requires that abortion seekers are referred to crisis pregnancy centers, which are often against abortion and give false information (for example, that abortion is linked to breast cancer) (National Abortion Rights Action League 2019; Guttmacher 2020a). Forcing abortion seekers to take time to go to these places and be required to listen to non-medical evidence based on religious views is ideological coercion based on religious-political preference. This is an important category, especially for women living in rural areas who are often burdened by reproductive rights policies; any extra waiting period, information session, or requirement is a barrier of time, transportation, and money to anyone seeking what is nominally a federally protected right (Pruitt and Vanegas Reference Pruitt and Vanegas2015).

To really expose the legal framing, variables include whether there are mandatory ultrasound requirements for abortions and whether state law criminalizes self-managed abortion (E. Nash Reference Nash2019; Center for Reproductive Rights 2020).Footnote 3 For some people living in religious areas or those in abusive relationships, the privacy of self-managed abortion is essential to personal safety (National Resource Center on Domestic Violence 2021). Likewise, the anti-abortion targeted regulations of abortion providers (TRAP) that each state supports can be separated into three categories (as broken down by their evaluating priorities: hospital admitting privileges, reporting requirements, and facility restrictions (Center for Reproductive Rights 2020; Guttmacher Institute 2020b). These regulations are regarded by medical and policy experts alike as being political interventions and not medically necessary (Guttmacher 2020b; Mukpo Reference Mukpo2020). This measure also captures whether there are restrictions on procedures and facilities that go beyond the TRAP laws (E. Nash Reference Nash2019; Guttmacher 2020b). Further, this category also includes whether a pre-abortion vaginal ultrasound is mandatory (a particularly traumatic process for sexual assault survivors and someone facing a rape-related pregnancy) (Center for Disease Control 2020b).

Because birth control and abortion decisions can be governed by economic circumstances, variables here also consider economic barriers as they relate to reproductive autonomy (Oaks Reference Oaks2015; J. Nash Reference Nash2021). These data were taken primarily from the Guttmacher Institute (2020a), the National Abortion Rights Action League (2019), and the Kaiser Family Foundation (2020) and include whether a state offers coverage for prescription birth control and under what circumstances they provide Medicaid for abortions. As the Guttmacher Institute (2020a, n.p.) reports,

12 states restrict coverage of abortion in private insurance plans, most often limiting coverage only to when the woman’s life would be endangered if the pregnancy were carried to term … 33 states and the District of Columbia prohibit the use of state funds except in those cases … where the woman’s life is in danger or the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest. In defiance of federal requirements, South Dakota limits funding to cases of life endangerment only.

These factors also include whether insurers must cover abortion through state insurance exchanges (Kaiser Family Foundation 2020) or whether state employees can buy abortion insurance through the state insurance exchange (Guttmacher 2020a). Variables here also include whether private insurers are required to offer abortion coverage (National Abortion Rights Action League 2019; Guttmacher 2020a); whether abortion coverage is banned and under what circumstances (Center for Reproductive Rights 2020; Guttmacher 2020a); what level of restriction exists through the state health-care exchange (Guttmacher 2020a); bans on public insurance coverage (Guttmacher 2020a); whether the state follows federal standards of only funding abortion in life-endangering situations or rape/incest (Kaiser Family Foundation 2020); and whether they only meet the lowest bar of federal minimum requirements.

Pregnancy and Parenting Variables

By looking at pregnancy and parenthood, variables in this category come from reproductive justice literature and include the right not only to have, but also to raise, a child. Taking the discussion beyond abortion/contraception is also crucial because, while the right to not be pregnant has been the primary struggle of white women, Black women and Latinas especially have faced legal and social forms of policing that are ubiquitous and speak to a history of reproductive coercion (the opposite of reproductive autonomy) that persists often through forms of forced sterilization and other methods of interfering in the right to have children (Gurr Reference Gurr2015; Sundstrom Reference Sundstrom2015; Roberts Reference Roberts2017; Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Davis Reference Davis2019; Luna Reference Luna2020). Forced sterilization, and assaults on (primarily) non-white women and poor white women, has been a persistent state-sponsored threat to reproductive autonomy. From the 1930s to the 1970s, approximately one-third of women in Puerto Rico were sterilized, many by force or without consent (Roberts Reference Roberts2017; Luna Reference Luna2020). By the 1980s, forced hysterectomies of Black women in the South were so common that they became known as “Mississippi appendectomies” (Roberts Reference Roberts2017; Davis 2020). Likewise, hundreds of Mexican women in the University of Southern California-Los Angeles County Medical Center were coerced during labor, including by threat to withhold pain medication, to be sterilized. A Senate investigation in 1987 revealed that doctors admitted to sterilizing approximately fifty women between the ages of fifteen and fifty (Silliman et al. Reference Silliman, Gerber Fried, Ross and Gutierrez2004, 229). In 2020, the US border agency—Immigration and Customs Enforcement—was accused of forcibly sterilizing migrant detainees without consent (Treisman Reference Treisman2020).

Silliman and colleagues (2004, 11, 119) also note the long history of reproductive coercion on Indigenous women—from the forced removal and kidnapping of their children to the use of Depo-Provera,Footnote 4 even before it was fully authorized by the Food and Drug Administration, including on those with cognitive impairments, despite lacking evidence on its safety. Thus, to only look at the right not to have children is to forgo an entire part of the real struggle for reproductive autonomy that exists regardless of whether women do or do not, can or cannot, or want or do not want to have children. The history of eugenics that has led to forced sterilization and medical mistreatment plays a part in some of these variables, as does the understanding that foster care, adoption, and IVF are all ways to understand reproductive autonomy (Washington Reference Washington2006; Oparah and Bonaparte Reference Oparah and Bonaparte2016; Roberts Reference Roberts2017).

Pregnancy and parenting include IVF access and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexuality, plus (LGBTQIA+) access in adoption and foster care. As Marcin Smietana, Charice Thompson, and France Twine (Reference Smietana, Thompson and Twine2018) have stated, LGBTQIA+ families may require alternate routes to reproduction, including IVF, foster care, and adoption, but they are not routinely included in IVF health-care policies, and many states allow legal discrimination against LGBTQIA+ parents in both foster care and adoption (LGBTMap 2020). IVF is an important variable because, even though some insurance companies may cover it, this coverage is often sporadic and not equal across the board (Kaiser Family Foundation 2020). Such coverage is usually predicated on a history of unprotected heterosexual sex that has not resulted in conception (Kaiser Family Foundation 2020). This is an extra burden on LGBTQIA+ families as well as intentionally single parents who intend to conceive. IVF variables are broken down according to states that require private insurance to cover some kind of fertility services or at least offer one plan to do so. There is another variable that includes whether Medicaid is required to cover or offer coverage for fertilization diagnosis, treatment, or both (Kaiser Family Foundation 2020). Together, these variables question the parameters of rights and the law’s neutrality in the wake of legal blindness to the broad scope of reproduction. Additionally, as abortion policies attempt to define conception as the beginning of life, this will continue to complicate IVF both with regards to the embryos that exist and to the potential for miscarriage that may necessitate abortions for the health of the gestational parent.

Drawing from reproductive justice and public health literature, pregnancy and parenting includes variables relating to incarceration, which could be considered both infrastructural and incidental. The rate of women in prisons in the United States rose 832 percent between 1977 and 2007; the United States currently incarcerates more women than any other country in the world (Goodwin Reference Goodwin2020). Variables relating to rates of incarceration are included because mass incarceration has specific effects on women’s health and on infant mortality rates (Maxwell and Solomon Reference Maxwell and Solomon2018). Because Black women have become particular targets of mass incarceration, and many of these women are mothers, it has become an important focus of public health research (Goodwin Reference Goodwin2020; J. Nash Reference Nash2021). This is an autonomy issue both in terms of the treatment of pregnant incarcerated people and because it is often the case that an inmate who gives birth is forced to place their child in a foster care system immediately (Juvenile Law Center 2018). The fact that the United States opts to incarcerate pregnant women in the prison system—where women already face a unique vulnerability to sexual abuse and increased risk of miscarriage (Just Detention International 2018; Goodwin Reference Goodwin2020; Amnesty International, n.d.)—exposes a place ripe for legal intervention. This measure includes statistics such as whether there is a state law that requires prisons to report the outcome of pregnant inmates, whether there is a law requiring pregnant prisoners to be given federally required nutritional needs, whether pregnant prisoners can be forced to give birth in handcuffs, and whether prisons are following the National Commission on Correctional Health Care’s guidelines for pregnancy counseling in prisons (American Civil Liberties Union 2021). Incarceration variables are particularly illustrative of state commitment to reproductive autonomy because measuring the state policy landscape by what rights privileged people can access only captures a measure of privilege, while measuring a state on its commitment to the most vulnerable and least politically powerful group shows a real commitment to autonomy (Enns and Koch Reference Enns and Koch2015).

Birth Choice

Sometimes called “the land that feminism forgot,” birth choice is separate from pregnancy and parenting because, in this category, there are both legal and health factors that intertwine in ways that are fundamentally different (Hill Reference Hill2019). Variables related to policies in childbirthFootnote 5 such as treatment in labor and delivery, which affect not only maternal mortality (Bailit Reference Bailit2012; Johnson and Rehavi Reference Johnson and Rehavi2013) but also the mental health and wellness of families (Diaz-Tello Reference Diaz-Tello2016), expose the ways in which the invisible hand of law and policy shape choices within health-care options. Synthesized from the public health and medical literature on childbirth (Johnson and Rehavi Reference Johnson and Rehavi2013; Vedantam Reference Vedantam2013; Gurr Reference Gurr2015), maternal mortality (Goodman Reference Goodman2014; Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Declercq and Shah Reference Declercq and Shah2018; Villarosa Reference Villarosa2018), and birth outcomes (Diaz-Tello Reference Diaz-Tello2016), these variables were selected to represent autonomy in childbirth.

Factors that affect birth choice include whether someone lives in an area defined by the March of Dimes (2020) as maternity care deserts—namely, places where there are so few birthing hospitals that there is no choice of provider. Birth choice has been overlooked likely because it is seen as being unimportant where someone gives birth or the rights that one has when they do give birth. While it may seem like one hospital is the same as any other, hospital culture plays a large role in birth outcomes (Johnson and Rehavi Reference Johnson and Rehavi2013; Vedam et al. Reference Vedam, Stoll, Marian, Declercq, Cramer, Cheyney, Fisher, Butt, Yang and Kennedy2018), particularly for Black women (Roberts Reference Roberts2017; Villarosa Reference Villarosa2018; Luna Reference Luna2020) and their babies (Davis Reference Davis2019), with Black babies being three times less likely to die when cared for by Black doctors (Greenwood et al. Reference Greenwood, Hardeman, Huang and Sojourner2020).

The choice of a birth attendant as well as the place also features in the medical literature as having a significant bearing on maternal outcomes (Bailit Reference Bailit2012; Johantgen et al. Reference Johantgen, Fountain, Zangaro, Newhouse, Stanik-Hute and White2012; Vedantam Reference Vedantam2013; Graham Reference Graham2014; Cramer Reference Cramer2021), including whether or not Medicaid covers doulas (labor support professionals and advocates) and midwives, both of which have consistent and positive effects on birth outcomes (Birth Place Lab 2015). Research has repeatedly found “a strong association between midwifery-led care for pregnant women and reduced labor and birth interventions” (Johantgen et al. Reference Johantgen, Fountain, Zangaro, Newhouse, Stanik-Hute and White2012; Raipuria et al. Reference Raipuria, Lovett, Lucas and Hughes2018, 387). Unpacking legal choice exposes the legal construction of birth choice. To capture the true preference, birth choice also includes whether or not a state allows home birth midwifery and offers licensure to certified professional midwives and lay midwives and whether the state restricts Medicaid to certified nurse midwives and whether they license certified midwives (Birth Place Lab 2015).Footnote 6 This is an imperfect variable, however, because as Renee Cramer (Reference Cramer2021) notes, licensing midwifery does not necessarily indicate state support for it or consumer access to it, but it does open up access (and, therefore, autonomy) by allowing homebirths and for other midwives to be covered under state insurance exchanges and makes a stronger case for those appealing to private insurance for coverage. In particular, the relationship between positive health outcomes and the presence of midwives (Johantgen et al. Reference Johantgen, Fountain, Zangaro, Newhouse, Stanik-Hute and White2012; Raipuria et al. Reference Raipuria, Lovett, Lucas and Hughes2018; Vedam et al. Reference Vedam, Stoll, Marian, Declercq, Cramer, Cheyney, Fisher, Butt, Yang and Kennedy2018) and doulas (Gruber, Cupito, and Dobson Reference Gruber, Cupito and Dobson2013; March of Dimes 2020), as well as the research from organizations like the March of Dimes (2020) calling for those birth workers to be reimbursed through Medicaid and other insurance plans, underpins the need for evidence-based medicine to guide law and policy on birth.

Health indicators that appear in birth choice are from medical literature and socio-legal studies like Birth Place Lab’s (2015) Mapping Midwife Integration project and the Local Reproductive Freedom Index representing interventionist laws (National Institute for Reproductive Health 2019). The rates of cesarean section, induction, spontaneous vaginal birth, and vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rates are included because research shows that cesarean rates and rates of induction are not reflective of women’s birth preferences (National Partnership for Women and Families 2006; Center for Disease Control 2020a) and are influenced by for-profit hospital status (Johnson and Rehavi Reference Johnson and Rehavi2013; Vedantam Reference Vedantam2013; Goodman Reference Goodman2014), which is a legal position as some states do not have for-profit hospitals (Kaiser Family Foundation 2020). Additionally, these variables represent non-evidence-based legal determinants of health because some hospitals have policies that deny all patients from having VBACs, despite the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the National Institute of Health recommending against such bans. VBAC bans are likely underestimated, and, while the International Cesarean Awareness Network (2009) has completed a study showing that, in some states, over 50 percent of hospitals have such bans, there is no way to know what the actual numbers are. Many hospitals without official bans have de facto bans, or doctors who refuse to work with VBAC patients, so it is virtually impossible to fully quantify the actual number of bans (International Cesarean Awareness Network 2009). If these hospitals are also listed under the variable of maternity care deserts (as they often are), this becomes a way of legally coercing someone to have a cesarean. Because law and policy do not forbid or punish such policies, they are within the realm of legality that shapes what options are available, including allowing hospitals to coerce major surgery against evidence-based medicine and the recommendations of the leading professional medical associations.

Background Socioeconomic Status Variables

Background socioeconomic status primarily represents those incidental laws, or the legal determinants of health, that “are factors that lie beyond the individual but effect the community level health outcomes, including culture, the economy, and corporate systems” (Oakes Reference Oakes2008, 1518). These variables include economic and social policies that “provide opportunities for public health intervention through policy” (1518). The theoretical reasoning is that these background socioeconomic status variables, while not specifically targeted toward those who give birth, are still going to shape reproductive autonomy by shaping economic choices, structural violence, living conditions, and rights generally (Martin Reference Martin2001; Morgen Reference Morgen2002; Gurr Reference Gurr2015; Sundstrom Reference Sundstrom2015; Pascucci Reference Pascucci2019). Again, we see that the “law is all over” not just in abortion but also in procreation more broadly (Sarat Reference Sarat1990). As Laury Oaks (Reference Oaks2015) notes, the decision whether to keep a pregnancy or a child can rest on socioeconomic status factors such as money, domestic violence, and culture, and emotional and material support are all incidental and therefore often excluded from studies of reproductive rights. Additionally, background socioeconomic status factors affect family and people of reproductive age, creating an environment where law is allowed to intervene in bodily autonomy and the family realm (Morgen Reference Morgen2002; Roberts Reference Roberts2017; Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017).

As the social determinants of health and reproductive justice literatures both contend, health equity and reproductive freedom are affected by social determinants, but it is important to point out that these variables are not just social but also legal in nature; emphasizing the legal nature of these determinants is a reminder that they are not accidental or unchangeable. These variables could include taxation policies and any number of economic and legal factors that might affect the health of populations (Putnam and Galea Reference Putnam and Galea2008) and generally concern the role of different parts of the political system (Galea Reference Galea and Galea2007). As Jennifer Nash (Reference Nash2021), Loretta Ross and Rickie Solinger (2017), and Sillman and colleagues (2014) note, the connection between reproductive autonomy and economics must be made clear, especially when considering economic assistance and tax policies that prioritize certain types of families.

Background socioeconomic status variables are the largest crossover between public health and socio-legal literature, and they comprise a necessary intervention to understand the scope of law and policy’s ability to affect what it means to have a reproductive right (Martin Reference Martin2001; Morgen Reference Morgen2002; Diaz-Tello Reference Diaz-Tello2016; Upadhyay et al. Reference Upadhyay, Dworkin, Weitz and Foster2014; Gurr Reference Gurr2015; Sundstrom Reference Sundstrom2015; Goodwin Reference Goodwin2016; Roberts Reference Roberts2017; Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Declercq and Shah Reference Declercq and Shah2018; Pascucci Reference Pascucci2019; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Fawson, Siegel, Jones and Stone2018; Senderowicz Reference Senderowicz2020). The percentage of women in state legislatures is included because studies show that states with more women in government are more likely to consider “women’s issues” such as reproductive rights, family leave policies, and domestic violence legislation (Didi Reference Didi2020) and how the state matters (Luna Reference Luna2020), and it also reminds us that not only do the laws themselves matter but also the lawmakers as shapers of reproductive choices (National Conference of State Legislatures 2019).

Likewise, exploring the state’s role in constructing vulnerability, socioeconomic status variables explore the role of power imbalances with regard to domestic violence. Thus far, studies of the effects of domestic violence on reproductive autonomy have been primarily focused at the medical or individual level (Planned Parenthood Federation of America 2012; Center for Disease Control 2020b; Saravi Reference Saravi2020), but this becomes more valuable as more studies connect public and political violence to a history of intimate partner violence (Bosman, Taylor, and Arango Reference Bosman, Taylor and Arango2019; Martin and Epstein Reference Martin and Epstein2021). The State Reproductive Autonomy Index uses socioeconomic status variables to explore the power of states in signaling their (un)willingness to protect domestic violence survivors, which relates directly to reproductive autonomy. Exposing the failure of states to take male violence, especially violence against their partners, seriously speaks to much of the literature on intersectionality, privilege, and the law. If male partners can harm women with impunity, then women can rightly see themselves as lacking in state protections and not as full rights-bearing citizens with the same level of legal protections under the law that is needed for reproductive autonomy to flourish. The ability of partners to leave complicates this situation, especially when there are no protections to keep people from being fired due to domestic abuse (for example, women being fired for being stalked at work or for former partners showing up and threatening them). The ability to say “no” to your partner regarding reproductive decisions and not to have the legitimate expectation of violence against you is fundamental to reproductive autonomy. States that ignore this element of protecting people, while restricting abortion and contraception access, demonstrate in practice, whether intentionally or not, a commitment to male sovereignty and female disempowerment.

Addressing the ability of women to leave an abusive relationship directly affects reproductive autonomy because, according to the Center for Disease Control (2020b), “almost three million women in the US will experience rape-related pregnancy during their lifetime,” most often from intimate partner violence. Additionally, “of the women who were raped by an intimate partner, 30% experienced reproductive coercion by the same intimate partner. Specifically, about 20% reported that their partner had tried to get them pregnant when they did not want to or tried to stop them from using birth control” (Center for Disease Control 2020b). According to the March of Dimes (2020), “more than 320,000 women are abused by their partners during pregnancy” each year. Further the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reports that one in six women first experience domestic violence during pregnancy.Footnote 7 Likewise, in Louisiana, “domestic violence [that is, male partners] kills more pregnant women each year than any other cause” (Woodruff Reference Woodruff2020, n.p.), and, elsewhere in the United States, it is in the top causes of death of pregnant women (National Institute of Health 2020; Woodruff Reference Woodruff2020; Planned Parenthood Federation of America 2012). The uniquely vulnerable position of those individuals surviving domestic violence is exacerbated by the precarious economic position of pregnancy and motherhood, especially for mothers with young children (Planned Parenthood Federation of America 2012; Saravi Reference Saravi2020). As Norsworthy, McClaren, and Waterfield (Reference Norsworthy, McLaren, Waterfield and Chrisler2012, 65) state, gender-based power imbalances, especially in economics, are significant drivers of reproductive coercion, making seemingly incidental laws fundamentally important background conditions.

Further understanding the role of power and violence in the lives of women, several variables explore gun rights as they relate to reproductive autonomy, including where there is a gun ban for those under domestic violence protective orders, those convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence, sex crimes, or stalking and whether there is a firearm surrender order for those convicted of misdemeanors or specific incidences of domestic violence. These variables were included because one in seven women (and one in eighteen men) have been stalked to the point where they consider themselves fearful that they will be harmed or killed (National Coalition against Domestic Violence 2020; National Resource Center on Domestic Violence 2021), and intimate partner violence accounts for half of all female murder victims (National Coalition against Domestic Violence 2020).Footnote 8 This rate of murder is higher in pregnancy and failure to curtail the ability of known domestic violence perpetrators from access to weapons is another example of states protecting the right to commit violence over the right of family safety (Woodruff Reference Woodruff2020).Footnote 9 According to the National Coalition against Domestic Violence (2020), “most intimate partner homicides are committed with firearms. … Abusers’ access to firearms increases partner femicide at least five-fold. When firearms have been used in the most severe abuse incidents, the risk increases 41-fold.” These variables measure the ability of women to experience autonomy (in this case, freedom from violence) in ways that affect reproduction. The diverse factors here flush out the contours of state commitment to reproductive autonomy and their willingness to intervene (or not) on behalf of vulnerable groups.

Understanding the position that economic freedom has in the choices that one makes, which are part of the background socioeconomic status variables, makes up more specific economic measures. These include whether there are employment protection or unemployment insurance benefits for survivors of domestic violence because states that protect domestic violence survivors are promoting autonomy (to leave the abusive relationship) and providing a legal safety net for parents and children to do so. In addition to interpersonal violence, this measure also includes institutional violence that keeps vulnerable populations vulnerable. Whether the state has a higher or lower average of women living in poverty or families with children headed by women living in poverty indicates whether states prioritize family wellness and shapes a person’s choices with regard to having a child, carrying a pregnancy to term, or raising rather than giving up a child (Oaks Reference Oaks2015). Additionally, the gender wage gap and an above average number of women workers in the lowest quartile of wage earners, and whether or not the state has policies for pregnancy and birth-related family leave, indicates the autonomy to have a child and maintain economic security (Status of Women 2015).

What socioeconomic status variables also do is complicate the discourse about reproductive autonomy by widening the field to include factors that create the background conditions for autonomy to exist and flourish. To add to the difficulty of political discussion, having reproductive autonomy is not as simple as saying “autonomy from state interference” since sometimes to have reproductive autonomy requires restrictions or tipping the scales in favor of one policy or another. Ultimately, this is why this article takes no normative position on interventionist or non-interventionist states and prefers to consider how to determine the substantive effects of intervention on autonomy.

EXPLORING THE REPRODUCTIVE AUTONOMY LANDSCAPE: STATES OF INEQUALITY

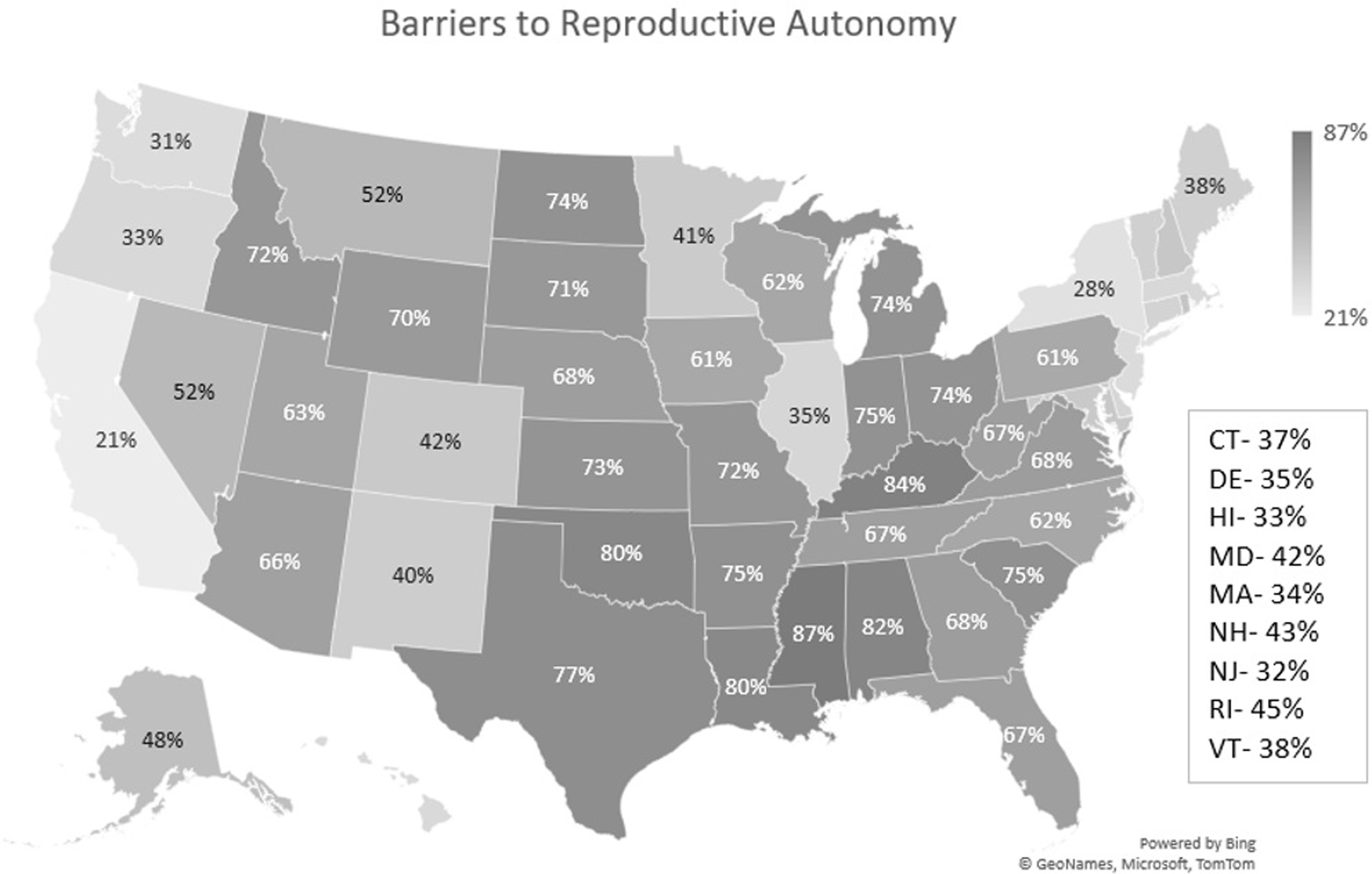

If there is a “floor” of constitutional rights, then what falls below that floor is unequal access to that which citizens are entitled. This type of legal mapping, with its emphasis on interventionist policies as well as incidental and infrastructural laws across related policy areas, exposes the ways in which states choose to approach the floor, and how they do so can mask a lack of access to rights and justice. The State Reproductive Autonomy Index offers a way to visualize inequality between states on matters of reproductive autonomy. Looking at the wide difference of reproductive autonomy among the states, we see 21 percent of barriers to autonomy in the lowest scoring state (California) and 87 percent in the highest (Mississippi). The substantial scope of inequality suggests that something very dramatic is going on with the distribution of reproductive autonomy and warrants a broad structural inquiry into how equal rights can exist so unequally, which brings us back to conversations on legal pluralism and what it means for equal rights. Looking at the measure in aggregate, as Figure 1 does, allows us to look at the subnational variation across the reproductive autonomy landscape. Figure 1 represents the aggregate total of all categories within the State Reproductive Autonomy Index based on variables between 2019 and 2021 (all data were taken from the most recent year available). Because a lower number indicates fewer barriers and more autonomy, a lower score equals a more autonomous state. States are color-coded with darker states having more barriers (and less autonomy) and lighter states having fewer barriers (and more autonomy).

FIGURE 1. Map of Reproductive Autonomy by state.

Drawing attention to the wide range between neighbor states brings us back to legal pluralism and questions about what this means for access to rights (31 percent in Washington versus 33 percent in Oregon; 72 percent in Idaho versus 40 percent in New Mexico; and 77 percent in Texas versus 80 percent in Oklahoma). Figure 1 shows that, in some ways, traditional blue states (most of New England and the West Coast) have fewer barriers to autonomy, while traditionally red states (Mississippi and Texas) have more. This is not unexpected in terms of reproductive autonomy, but it does also call into question the false dichotomy of calling some states “nanny”—or intervention heavy—and some libertarian states because those labels do not appear to show libertarian “hands-off” policies in conservative states or nanny-esque meddling in liberal states. The ideology for or against restricting personal liberties used in typical polarized discourse is not evident here (Rhodes and Vayo Reference Rhodes and Vayo2019); rather, we are seeing a matter of which—and whose—liberties are restrictable in each state, and those with higher percentages show a willingness to restrict autonomy when it comes to reproduction.

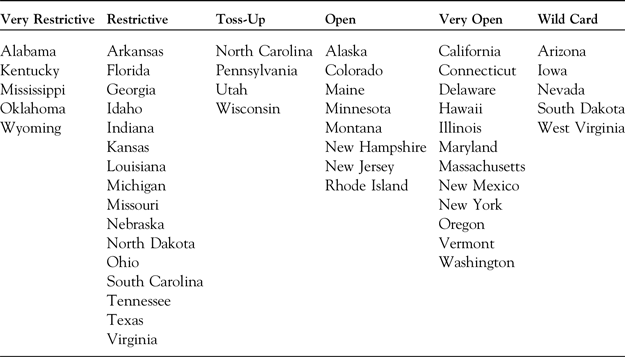

To show which states are restricting whose rights, Table 1 offers typologies based on where each state fell when measuring the disaggregated subgroups (abortion and contraception, pregnancy and parenthood, birth choice, and socioeconomic status). When looking at the totals in the subgroups, very restrictive states are in the fourth quartile three or more times, restrictive states are in the third or fourth quartile three or more times, and toss-ups are split evenly between the second and third quartile. Open states are in the first or second quartile three or more times, and very open states appear in the first quartile three or more times. Five states are listed as wild cards, meeting none of the criteria above and showing a wide range across the variables (for example, South Dakota is in the second quartile on background socioeconomic status and birth choice, but in the fourth quartile on abortion and contraception and pregnancy and parenthood). Table 1 offers a companion way of looking at the national map because it exposes the ways in which some states have higher or lower numbers in aggregate because of particular policy parameters; the typologies break through this portrayal and show the larger patterns that can be masked by the aggregate.

TABLE 1 Typologies of States

Abortion and Contraception

An obvious driver of high percentages in many states, the abortion and contraception variables range tremendously from 3 percent in California to 81 percent in Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and South Dakota. What is concerning about this from a legal pluralism standpoint is that abortion and contraception variables represent those most litigated in state and federal courts and those covered by federal law, illustrating Sandra Levitsky’s (Reference Levitsky2013) concern that constantly litigated rights may not be rights at all. Many of the other variables relate to social policies typically reserved for the state governments to decide; however, abortion and contraception are supposed to be governed by some level of federal floor, but what Figure 2 shows is that this is not the case.

FIGURE 2. Abortion and Contraception Barriers by State.

When exploring the connection between legal pluralism and rights, this part of the findings even more than others highlights the way in which law is used to deny rights or expand them based on the political climate and questions whether federalism can sustain such inequality. Further, Figure 2 exposes some of the dangers that much of the country will face if the US Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade. Figure 2 is the map of abortion and contraception barriers when there are laws in place guaranteeing access to these rights; without a federal law to even nominally limit state ability to restrict them, this map could look far more unequal. One could look at access in some of these states as matters of geographical difficulty where larger states and rural states in the West and South have a harder time creating abortion clinics to serve rural and sparsely populated areas, but, given that rural states in New England, like Maine, and states that are geographically large and also have rural, sparsely populated areas like New York, California, and Oregon, it would indicate that abortion clinic deserts and lack of access to abortion and contraceptive care are policy choices where political will, rather than geographical constraints, matter more. This is especially obvious in neighbor states like Montana that share some politically conservative values and geography-population barriers to policy with North and South Dakota, but Montana has only 31 percent of barriers and North and South Dakota have 81 and 77 percent respectively. Neither widespread political values, states’ rights ideologies (Enns and Koch Reference Enns and Koch2015), or geographical conditions appear to be driving the differences (in fact, the neighboring states are similar in all other subcategories); instead, it appears to be attitudes about abortion and contraception particularly.

Pregnancy and Parenthood

Looking at pregnancy and parenthood reveals many barriers to becoming parents. The pregnancy and parenthood variables raise questions about what it means to be a “family values” state and, indeed, how willing states are to regulate what counts as a family. The pregnancy and parenthood totals indicate that those states that regulate abortion and contraception so thoroughly do not appear to support parenthood and are also likely to restrict autonomy in pregnancy and parenthood. This lends credence to the feminist argument that restrictions on abortion and contraception are about controlling bodies, choices, and autonomy and not about valuing families and children. If states were pro-child and pro-family, the path to parenthood would be clearer and more accessible, including IVF and in foster and adoption care, but as Dorothy Roberts (Reference Roberts2017) and Harriet Washington (Reference Washington2006) have pointed out—from eugenics and sterilization to welfare policies (Briggs Reference Briggs2017)—states have a history of using laws to decide which groups are “fit” to become parents and get support (Oaks Reference Oaks2015; Oparah and Bonaparte Reference Oparah and Bonaparte2016; J. Nash Reference Nash2021)—either positively (access to economic/insurance help IVF) or negatively (denying access to birth control or abortion).

As Laura Briggs (Reference Briggs2017) and Julia Oparah and Alicia Bonaparte (2016) explain, reproductive autonomy in pregnancy and parenthood take many different forms and are shaped by social factors from community engagement to economic policies. When those policies exclude some parents from IVF based on income, that is the state declaring that poor people do not deserve to reproduce and people with means do. Likewise, as Zakiya Luna (Reference Luna2020) contends, the right to have a child is a human right, but that right has been strictly controlled by who has access to money, medical technologies, and the benefit of the law.

Figure 3 reveals that some states have developed a strong policy of excluding families, particularly those seeking financial help in conceiving and those who are LGBTQIA+. Looking at Figures 2 and 3, we can see that, in states where abortion is regulated and adoption is seen as a suitable alternative, adoption itself is still regulated by who the state sees as “fit.” States like Mississippi (100 percent use of barriers) and Alabama (92 percent use of barriers) are very restrictive in their typology and are in the higher states when it comes to abortion and contraception and are among those that use the rhetoric of family values, but when looking at those states that use fewer barriers to parenthood, we see the more liberal states of Connecticut (23 percent use of barriers) and California, New York, and New Jersey (31 percent use of barriers) among those providing benefits to families. This data empirically challenges the rhetoric of family values as evidence of policies that value families.

FIGURE 3. Barriers in Pregnancy and Parenthood by State.

Birth Choice

Figure 4 shows the situation with barriers to birth choice. Birth choice is an area that closes the inequality gap among states because most states are restrictive in some way. In this group, no state is in the bottom quartile, and almost all states use 50 percent of the barriers or more, meaning that, even in politically liberal states, which use fewer barriers overall, birth is still regulated and restricted at higher levels. This is an area that showcases the ways in which politics, and not medicine, shape access to rights and autonomy in childbirth. Even a state like California, which has made a sustained effort to end maternal mortality and lower cesarean rates, uses 50 percent of the barriers. States where we see higher maternal mortality rates like West Virginia, Kentucky, and Mississippi all use 90 percent of the barriers to autonomy in childbirth, supporting both the social determinants of health contention that non-clinical factors shape health outcomes (Goodman Reference Goodman2014; Diaz-Tello Reference Diaz-Tello2016; Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Declercq and Shah Reference Declercq and Shah2018; Villarosa Reference Villarosa2018) and reproductive justice theories on the role of state policy and attitudes toward those who give birth as effecting health outcomes broadly (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Davis Reference Davis2019; Luna Reference Luna2020; J. Nash Reference Nash2021).

FIGURE 4. Barriers to Birth Choice by State.

For birth choice to be this regulated brings all states up in the final calculation of barriers, so even typically low states like California get a bump in the aggregate. More than any other group, birth choice variables illustrate why it is important to explore the disaggregated categories. California is generally in the bottom five of the barriers in each category, but here they are closer to the median restrictive state, highlighting the need to disaggregate the data when one is looking at particular policies. Conversely, Florida is often in the top quartile, but is relatively low here. State priorities in policy to support reproductive autonomy as judged by the other three groups but lacking here indicate that birth choice is an even more invisible category than other barriers.

Background Socioeconomic Status

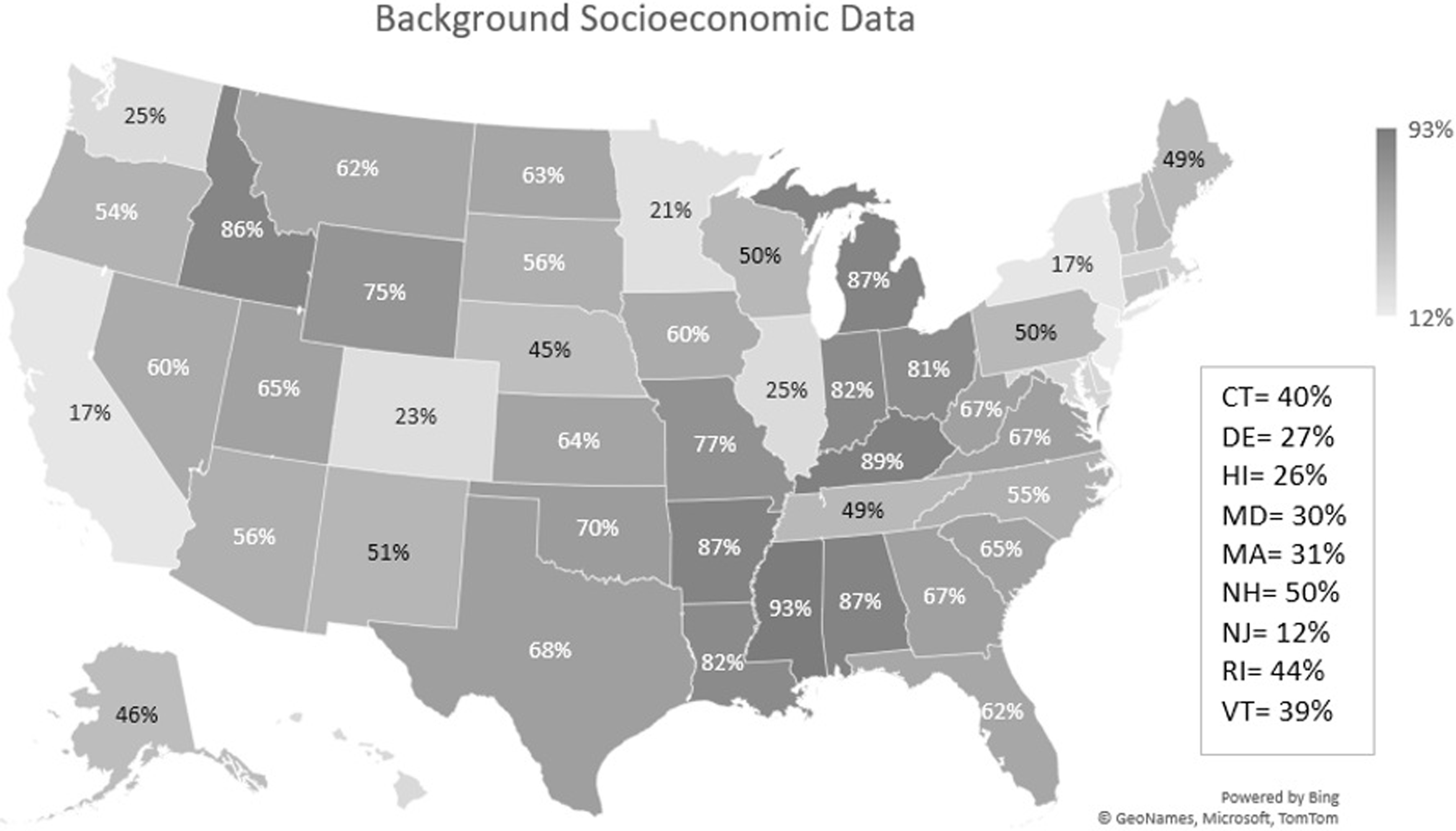

A key component of understanding the landscape against which reproductive autonomy happens is the background socioeconomic status. Figure 5 identifies background socioeconomic status and exposes the ways in which social and economic policies in each state can shape reproductive autonomy. Socioeconomic status barriers create conditions that affect health and wellness (Putnam and Galea Reference Putnam and Galea2008; Maxwell and Solomon Reference Maxwell and Solomon2018; Coggon Reference Coggon2020), exacerbate racial disparities in maternal care and parenting (DeClercq and Shah 2018; Roberts Reference Roberts2017; Kawachi, Daniels, and Robinson Reference Kawachi, Daniels and Robinson2005), and shape economic conditions that affect access to abortion.

FIGURE 5. Background Socioeconomic Data.

Drawing from reproductive justice theorists on the role of reproductive rights as human rights (Ross and Solinger Reference Ross and Solinger2017; Luna Reference Luna2020) and the role of welfare policies (Briggs Reference Briggs2017), this group of variables captures the conditions that make reproductive autonomy possible. These variables are ones that could be most clearly identified as those that value families; where the state literally values families by providing financial benefits or protections and values families in terms of protecting them from the threat of violence. Not only do the totals on this map suggest that families are valued very differently across states but that those states known for using the rhetoric of family values in abortion and contraception are not using the policies of family values in socioeconomic status factors. Because so much of this measurement includes socioeconomic data, it makes sense that poorer states would score as using higher barriers (because they would lack the money to provide social safety nets), though those states could access federal funding for many of the variables measured. However, states that also have shown resitance to the Affordable Care Act score lower in this category as well, showing that political will surrounding particular issues as well as political mood generally can shape state choices for or against reproductive autonomy (Enns and Koch Reference Enns and Koch2015).Footnote 10

The inclusion of domestic violence and gun violence variables are not explained by economics but, rather, by ideology. States that have higher gun rights ideology and lower economic ability, score very high on background socioeconomic status overall, like Missippi (93 percent), Idaho (86 percent), and Kentucky (89 percent). However, states like Texas (68 percent) manage to be pro-gun without being scoring a high number of barriers because there are a number of protections on other metrics.

CONCLUSION: LEGAL PLURALISM AND RIGHTS IN DISARRAY

In one of his last skits before his death, comedian George Carlin references Japanese internment during the Second World War, saying that this event proved “there’s no such thing as rights … rights are an idea, they’re imaginary.” Using legal mapping to visualize the extent to which legal pluralism results in wildly different legal realities and access to rights, one wonders whether the famously cantankerous comedian is correct. The State Reproductive Autonomy Index provides a comprehensive view of the state variation in access to reproductive autonomy across the United States as well as a more nuanced understanding of the landscape as it shapes access to rights in specific reproductive areas. Legal pluralism where customary law or norms collide with law on the books is a matter for societies to navigate as part of the life course of law and does not necessarily represent a lack of rights; however, within a single constitutional federal republic, when there appears to be no floor of equal protection, legal mapping can cause us to ask whether legal pluralism is the guise for denying rights to people in areas that governments simply do not want to allow.

The State Reproductive Autonomy Index allows us to calculate what equality looks like at the state level, offering a way to compare states on interlocking policies and explore the limits of legal pluralism’s inequality. Creating state profiles gives policy makers and activists in each state a context and scope for discussion. While the method is useful to scholars as a roadmap to pull out the interlocking structures of other persistent and widespread political-legal issues, this index is also useful to social scientists broadly because reproductive autonomy is a crucial part of a person’s rights. Reproductive autonomy shapes the lives of every person on the planet—because even those who do not give birth are born—and all people who present as women and anyone with a uterus must live in a context that may regulate their choices during their presumed reproductive years. Using the State Reproductive Autonomy Index itself will be a way for researchers to categorize the status of women and families in any given state.