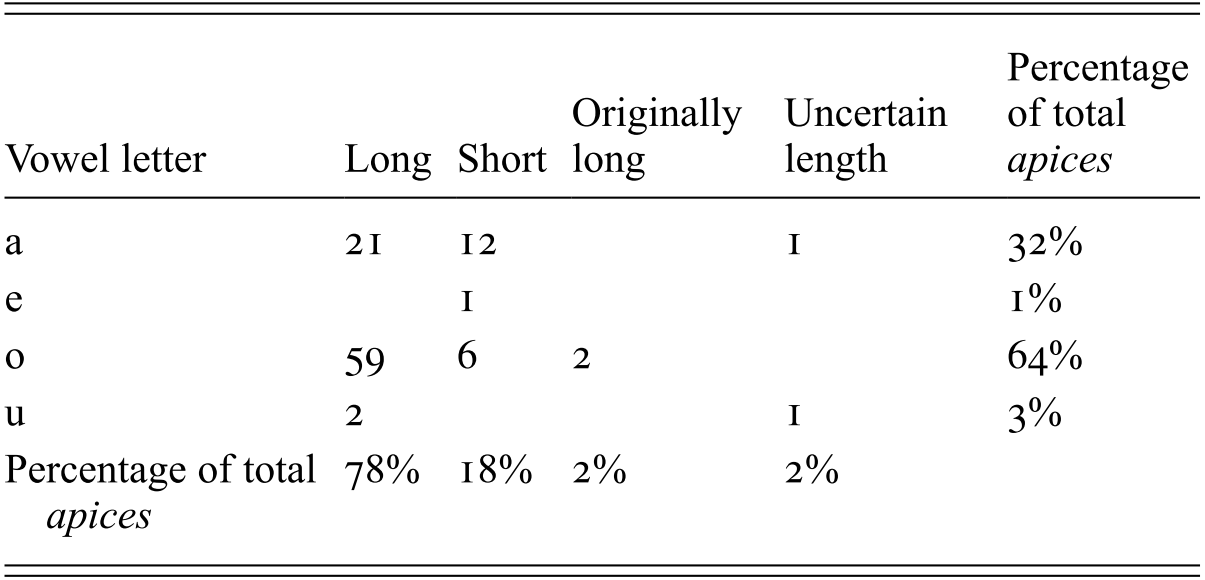

Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 97–8, Reference Adams2003: 531–2) collected most examples of apices in the Vindolanda tablets in Tab. Vindol. II and III. Including some doubtful cases, he counts 92 instances. We can add a further 7 found in the more recently published tablets, and 6 which he omitted.Footnote 1 With the new cases we have a total of 105 instances of apices (Table 35), of which 82 = 78% are on long vowels, and 19 = 18% are on short vowels, with a further 2 = 2% on vowels which were short but used to be long, and 2 = 2% on vowels of uncertain length (Table 36).Footnote 2

Table 35 Apices in the Vindolanda tablets

| Long vowels | Text (Tab. Vindol.) | Short vowels originally long | Text (Tab. Vindol.) | Short vowels | Text (Tab. Vindol.) | Vowels of uncertain length | Text (Tab. Vindol.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 194 |

| 645 |

| 175 | censúsFootnote a | 304 |

| 196 | -neariá | 192 | FrámFootnote b | 734 | ||

| 212 |

| 198 | ||||

| 215 | sagá | 207 | ||||

| Fláuio | 221 | óptamus | 248 | ||||

| Octóbres | 234 |

| 265 | ||||

| 239 |

| 291 | ||||

| numerátioni | 242 | necessariá | 292 | ||||

| 243 | t.[c. 6.]áFootnote c | 588 | ||||

| -róFootnote d | 245 | mágis (possibly) | 611 | ||||

| tú | 248 | dómine | 628 | ||||

| Flauió | 255 |

| 645 | ||||

| suó | 261 | diligénter | 693 | ||||

| tuó | 263 | dómine (possibly) | 796 | ||||

| 265 | ||||||

| 291 | ||||||

| 292 | ||||||

| 305 | ||||||

| exoró | 307 | ||||||

| suó | 310 | ||||||

| 311 | ||||||

| 319 | ||||||

| -innáFootnote f | 324 | ||||||

| ]..s.nióFootnote g | 325 | ||||||

| meó | 330 | ||||||

| Licinió | 580 | ||||||

| stabuló | 581 | ||||||

| á | 588 | ||||||

| [r]ạtió | 608 | ||||||

| 611 | ||||||

| Flauió | 613 | ||||||

| Lepidiná (possibly) | 622 | ||||||

| 628 | ||||||

| suó | 631 | ||||||

| Flauió | 632 | ||||||

| 640 | ||||||

| Ṃarinó | 641 | ||||||

| Flórus | 644 | ||||||

| 645 | ||||||

| Flauió | 648 | ||||||

| fació | 652 | ||||||

| Priscinó | 663 | ||||||

| benefició | 666 | ||||||

| illórum | 693 | ||||||

| immó | 706 | ||||||

| tuá | 880 | ||||||

| 893 | ||||||

| Decmó | 893 add |

a The editors suggest a gen. sg. censūs, but the context is damaged, and nom. sg. census cannot be ruled out.

b On the back of a tablet, probably a name in the address of a letter.

c Perhaps tr[ansla]tá.

d Probably part of a name.

e But the text is not certain here.

f Probably a name in the ablative.

g This is in the address on the back of the letter: it will be a name in the dative.

Table 36 Distribution of apices in the Vindolanda tablets

| Vowel letter | Long | Short | Originally long | Uncertain length | Percentage of total apices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 21 | 12 | 1 | 32% | |

| e | 1 | 1% | |||

| o | 59 | 6 | 2 | 64% | |

| u | 2 | 1 | 3% | ||

| Percentage of total apices | 78% | 18% | 2% | 2% |

It seems likely that use of apices was a practice restricted to, or at least most common among, scribes at (and around) Vindolanda. While it is not always easy to tell whether a given tablet at Vindolanda was written by a scribe or by another writer, letters often feature a second hand which provides the final salutation formula, and in these cases it is reasonable to suppose that the first hand is that of a scribe. Sometimes these hands also appear in other texts. The following texts have apices in scribal parts: Tab. Vindol. 234,Footnote 3 239, 242, 243, 245, 248, 263, 291, 292, 305, 310, 311, 611,Footnote 4 613, 622, perhaps 628,Footnote 5 641, 706. Conversely, there are very few or no examples of apices in texts which we know or suspect not to be written by scribes, such as the letters written by Cerialis (225–232), the renuntium reports written by the optiones (127–153), the relatively long closing messages of Lepidina at 291 and 292 (both letters where the scribe uses apices), the letters of Octavius (343) and Florus (643),Footnote 6 and the writer of the letter 344 and accounts 180 and 181.Footnote 7 Of course, it may be that there was a feeling that letters were more formal documents than other types of text, so that use of apices in them may have been more appropriate, as Adams suggests (see fn. 14). However, this does not explain why we don’t find apices in the parts of letters written by non-scribes.

Furthermore, the scribes appear to have been trained in, or to have developed among themselves, a usage of apices that is characteristic of the Vindolanda tablets. Firstly, use of the apex is highly restricted in terms of vowel quality, with /aː/ and /ɔː/ making up practically all the vowels with an apex (101/105 = 96%); secondly, it is highly restricted in terms of position in the word. Not including monosyllables, of which there are 5, 80 (= 80%) instances of the apex are on the final syllable, 76 (= 95%) of these are on an absolute word-final vowel,Footnote 8 and 75 (94%) are on <o> or <a>.Footnote 9 This means that out of all 105 instances of apices, 71% are on absolute word-final <o> or <a>. Now, these are doubtless the most frequent word-final vowels in Latin, probably both in terms of type within the language and token within most texts, but the disproportion in terms of both apex position in the word and letter on which the apex is placed marks the Vindolanda tablets out from other texts containing apices (as we will see in Chapter 21).

Reference AdamsAdams (2003: 531) makes two possible suggestions for the preponderance of final <ó> and <á>:

either that a stylized form of writing is at issue, such that writers, if they remembered, signed off words ending in one or the other of the two long vowels with a sort of flourish, or, if a linguistic explanation is to be sought, that long vowels in final position were subject to shortening in speech, and that scribes were encouraged to use the apex as a mnemonic for preserving the ‘correct’ quantity.

It seems to me less likely that Adams’ linguistic explanation is correct. It is important to note that nearly every word-final /ɔ/ in Latin was long (and all examples of short /ɔ/ came from original /ɔː/, by iambic shortening). This was not the case with /a/ and /aː/. Therefore, if shortening of absolute final vowels had occurred, and the scribes were trying to mark vowels that ought to be long, they would succeed simply by putting an apex on practically every word-final <o>. When it came to <a>, however, such an approach would not work. Indeed, this is what we find: there are only 8 examples of long final /aː/ with an apex, but 9 of short final /a/.

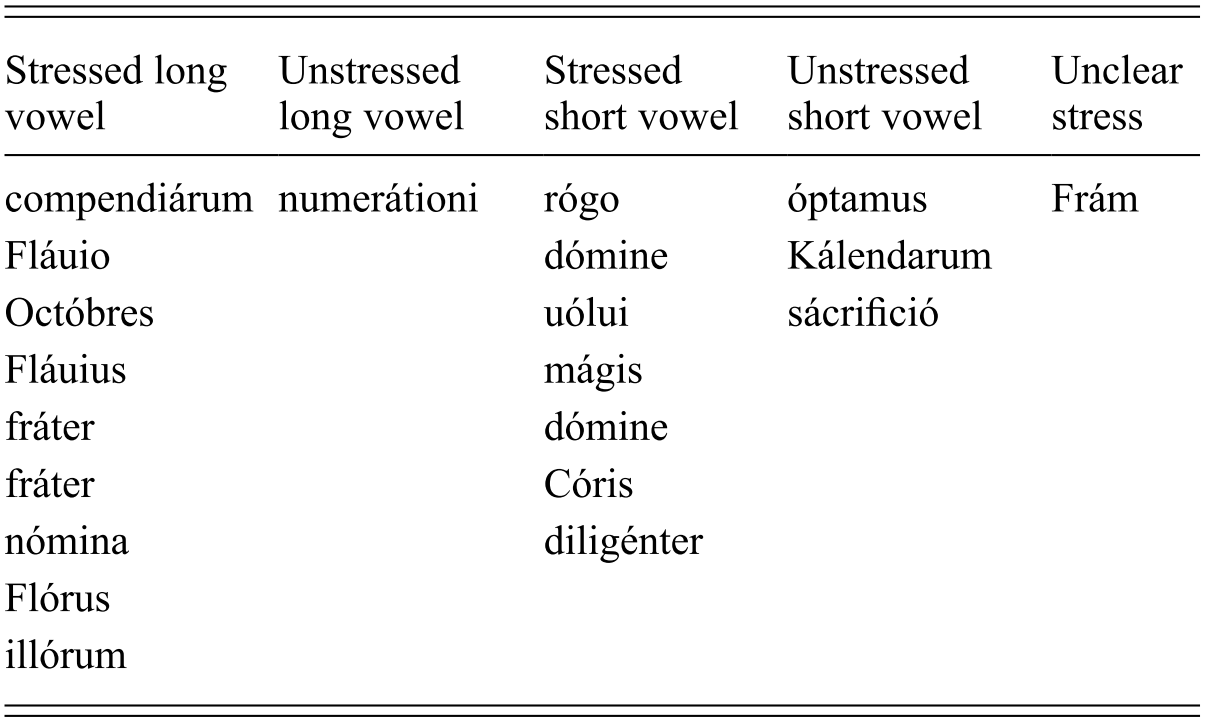

On the face of it, therefore, this is evidence in favour of shortening of word-final vowels: in cases where the scribes actively had to recognise whether an /a/ was long or short, they could not. However, it seems somewhat surprising that the scribes, who were so successful in producing non-intuitive standard spelling in other ways, had not managed successfully to learn this particular feature. Moreover, if the apex was taught as a means of maintaining the correct quantity, it is surprising that we find it so often on final /ɔ/. After all, since there are practically no words which differ in meaning depending on whether final /ɔ/ is long or short, the value in marking it is very little compared to that of final /a/ and /aː/.Footnote 10 Nor is there any point, from this perspective, in the three examples of word-final /aːs/ in which the vowel bears an apex, since there are no verb forms ending in /as/ with which they could have been confused (nor was there a shortening taking place of non–word-final vowels). In addition, when apices are used on non-final syllables, they appear with equal frequency on short vowels as on long vowels (10/20 instances; see Table 37), even though vowel length was still maintained in non-final syllables at this time.Footnote 11 All of this suggests that marking vowel length may not have been the primary purpose of the apex.

Table 37 Apices on vowels in non-final syllables at Vindolanda

| Stressed long vowel | Unstressed long vowel | Stressed short vowel | Unstressed short vowel | Unclear stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compendiárum | numerátioni | rógo | óptamus | Frám |

| Fláuio | dómine | Kálendarum | ||

| Octóbres | uólui | sácrifició | ||

| Fláuius | mágis | |||

| fráter | dómine | |||

| fráter | Córis | |||

| nómina | diligénter | |||

| Flórus | ||||

| illórum |

Given the divergence of the placement of the apex at Vindolanda from what Quintilian and ‘Scaurus’ say about the apex, and indeed its divergence from other inscriptions and corpora discussed below, it seems reasonable to assume that the scribes were using apices according to their own rules or sense of where an apex was appropriate, which can only be derived from the evidence of the Vindolanda tablets themselves. Although these rules or feelings were not necessarily shared by all scribes, or used consistently by any given scribe, overall we can identify some tendencies. Starting from this position, without preconceived ideas, the most important principle seems to be that the apex should appear on /ɔ(ː)/ or, less often, on /a(ː)/; the next most important that it should appear on a vowel in the final syllable of a word (ideally on a vowel which is word-final).Footnote 12 Given these principles, it is inevitable that most apices will end up on long vowels (or at least vowels which were originally long, if shortening of word-final long vowels has taken place), but this will be epiphenomenal, rather than being a principle in itself.Footnote 13

If the reason for these ranked principles is not linguistic, what is it? It could be connected with the fact that apices seem to be used more in letters than in other types of text.Footnote 14 Using the list showing all tablets from Tab. Vindol. II and III, at Vindolanda Tablets Online II,Footnote 15 I count 129 non-letters, and 206 letters. There are 67 documents containing apices, of which 54 are letters, 12 are not, and 1 is uncertain. The proportion of documents containing apices that are letters is thus much higher than the proportion of letters as a whole at Vindolanda.Footnote 16 There is other evidence that it was a feature of letter writing for apices to have been used on word-final <o> of datives in the greeting formula in the prescript of a letter or the address of a letter on the back, a usage which continues into the third century AD in papyrus letters (Reference KramerKramer 1991: 142; Reference Bowman and ThomasBowman and Thomas 1994: 60–1).Footnote 17 About a third of apices at Vindolanda occur in this context, almost all of them on final <o>. Indeed, there are a certain number of letters where an apex does not appear anywhere except in this context.Footnote 18 A plausible instance of these factors being important is Tab. Vindol. 893, a letter whose author was Caecilius Secundus, the prefect of a unit, probably in the late 80s AD. There are five datives of the second declension with final /oː/, and all five are marked with an apex. Two of these are found in the greetings formula (Vẹrecuṇḍó suó), and two in the address on the back (Iulió Vẹṛecundó), and the remaining instance is a proper name coming directly after the greeting (Decuminó). No other vowels are marked in the text, which includes one other instance of word-final /ɔː/ in scito and several of long final /aː/ (de qua re, in praesentia, as well as the preposition a).

With regard to the position of apices in non-final syllables, Reference Bowman and ThomasBowman and Thomas (1994: 60) have suggested that the presence of the accent may be relevant. As Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 97–8, Reference Adams2003: 531–2) points out, this is not an appealing argument on the basis of Occam’s razor, since this factor cannot explain the far greater number of apices on the final syllable. It is true that there is a certain amount of correlation between apices on non-final syllables and the position of the accent, with 16/20 (= 80%) of instances of apices appearing on vowels in stressed syllables. However, almost the same success rate is found by positing a rule that apices must appear on the initial syllable of a word (16/21 cases = 76%).Footnote 19 Ultimately, the problem is the slightness of the evidence.

I conclude that the very specific tendencies around apex use at Vindolanda probably are not based around their use of diacritics for linguistic purposes, but more as markers of the different part of the text. This would be rather similar to their usage in the Isola Sacra inscriptions. In addition to the tendency for apices to be used in greetings formulas which I have already mentioned, we also find the opposite pattern, where the main text contains apices, which are lacking in the greeting. For example, the brief letter Tab. Vindol. 265 contains a high number of apices, all of which come after the greeting formula C̣ẹṛịạlị suọ salutem. Almost every subsequent instance of /a(ː)/ receives one (fráter, sácrifició, kálendarum, uọluerás), along with word-final /ɔː/ in sácrifició (and not ego). This also has the effect of marking the different parts of the letter. The same pattern is found in 248.

This is not to say that this type of text-marking was the only function of the apex. Sometimes, it seems to have been used out of pure exuberance, and without consistency. An interesting case is the collection of letters Tab. Vindol. 243, 244, 248 and 291, all written by the same scribe. In 291, in the sections written by the scribe, almost every word-final vowel, whether long or short, receives an apex (only tuo is without): salutá, rogó, interuentú, and short /a/ in Seuerá (in the greeting formula) and facturá; in addition, f̣aciás has one on a non–word-final vowel (although in a final syllable; no apex is found on uenias, nos). In 243, a five word fragment, apices appear on suó (in the greeting formula) and fráter, but not on the long vowels of C̣eṛiạli or saluṭem. 244 uses no apices, although only the line Seuera mea uos salutat and the address Flauio Cerialị survive. The largely undamaged 248 uses an apex only on óptamus and tú, but not on the only examples of word-final /ɔ(ː)/ (suo, in the greeting, and pro; there are no examples of word-final /a(ː)/), nor on the other instance of op<t>amus, nor the two other instances of frater, which received an apex in 243.

By comparison, Tab. Vindol. 645 is a long letter, which fits much better than those written by the scribe of 243 etc. into the normal tendency at Vindolanda to use an apex on word-final /a(ː)/ and /ɔ(ː)/:Footnote 20 meó, gesseró, fussá, egó (twice), morá, s[[s]]ummá, Cocceịió, Maritimó (the last two in the address), and ịṭá (on a short /a/, if it is read correctly). According to the editors, the remaining instances of meo and of egọ may have had apices which were lost; otherwise in the main body of the letter only pro and opto remain without an apex on word-final /aː/ or /ɔː/, along with eo, quo in the postscript written between the columns, in which haste or space may have been a factor. There is also an apex on an initial vowel in uólui.Footnote 21

Although consistency within a single document or across all of a scribe’s output may not have been of great importance, the shared tendencies suggest that as a group the scribes of Vindolanda had developed their own habits of usage for apices.