In a consolidated democracy, an independent, impartial, and efficient judiciary is an inevitable player for securing human rights, the rule of law, and democracy. After the fall of Communism, countries in Central and Eastern Europe have all faced the task of reorganizing their judiciaries to correspond to these values. In many countries, however, this process takes place in the context of increasing conflict between different ethnic groups. In the former Soviet Union, the democratic transition and the restoration of independence of small nation-states also brought about the transformation of the minority status: the formerly dominant ethnic group—the Russians—became a minority. Can newly democratic courts be fair to people of the very ethnic group that used to oppress them? To what extent do ethnic tensions enter the arena of judicial decisionmaking? In order to answer these questions, we need to understand the empirical regularities of judicial behavior in ethnically divided transitional societies. The fact that judges decide cases not only based on the relevant legal provisions, but also influenced by their individual attitudes, beliefs, and values, is well-known in the political science literature. In the United States, for example, this has been observed on the level of both the Supreme Court (Reference BaumBaum 1997; Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 2002) and trial courts (Reference Ashenfelter, Eisenberg and SchwabAshenfelter, Eisenberg, & Schwab 1995; Reference Hagan, Bumiller, Blumstein, Cohen, Martin and TonryHagan & Bumiller 1983; Reference Steffensmeier and BrittSteffensmeier & Britt 2001).

In this article, we examine two potential sources of bias in the transitional judiciary. First, we examine the assumption that service under the old regime taints judges in their later decisionmaking. The replacement of unqualified or unacceptable personnel from the pretransition period with newly trained judges is an important aspect of judicial reform in many transitional countries. Such replacement also assumes that judges from the previous regime behave differently than the newly appointed ones, who have arguably not been “corrupted” by the old system. Testing the empirical validity of this assumption both advances our understanding of the judiciary in transition and has explicit policy relevance to decisions about court personnel reform in new democracies.

Second, we analyze whether judges in the newly democratic courts can be fair to people of the very ethnic group that used to oppress them. The integration of different cultures in a single society is a prominent challenge facing former Communist countries (and other countries as well). In Eastern Europe, ethnic discrimination is a well-known problem addressed by different international organizations. Knowing that the courts can, in fact, be impartial and protect minorities from discrimination assures that strengthening the judiciary is a valuable measure to protect minorities from discrimination.

The first section of the article gives some background information about the transitional country under study: Estonia. Next, we present the theoretical framework, methods, and results of our empirical analysis on trial-level courts. We have created for the analysis an original dataset of a sample of decisions by trial-level judges in Estonia. The findings indicate that a judge's experience under the previous regime does not seem to be an important factor in judicial decisionmaking. We also find that the Russian ethnic minority does not fare differently in the courts from the current ethnic majority. We believe that the study serves as a useful basis for further investigations and theory-building on judicial behavior in nascent democracies.

Judicial Reform and Discrimination in Estonia

Estonia regained its independence in 1991 after half a century of Soviet rule and, like other Central and East European countries, went through a regime change. This country is a particularly interesting locus for the current study for two reasons. First, during the judicial reform period in the early 1990s, court personnel were partially replaced. As a result, those judges who were members of the criminal justice system under the previous regime now work side by side with the “new” judges. Second, Estonia is one of the countries that was dominated by ethnic Russians under the Soviet regime. This dominant group, however, suddenly became an ethnic minority after Estonia regained its independence, creating a situation where discrimination against Russians was especially prone to emerge.

The Change in Judicial Personnel

After Estonia became an independent democratic nation in 1991, it faced the challenge of transforming the Soviet judiciary into a democratic and independent one. The selection of personnel was among the most difficult tasks in this process. A supply of new personnel was never available, and the dismissal of the “old” judges was not very easy—the mere fact that a person had been employed by the government structures of the previous regime was not sufficient for dismissal in Estonia.

Major judicial reform took place primarily in 1993. As part of this reform, all judges, including those nominated during the Soviet regime, had to go through a reappointment procedure. In order to become a judge, a recommendation by the Supreme Court plenary and an appointment by the president of the Estonian Republic were necessary. All new applicants (i.e., not including those who were judges before the reform) had to pass a judicial examination before the Supreme Court could consider their candidacy. The reform did not concern the Supreme Court, which was a new institution created after independence and whose members had been appointed by the Parliament before the major judicial reform period. Before the transition, the Supreme Court of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic was the highest judicial authority, but almost no data exist about the institution. The influence of the Communist Party over the court is generally acknowledged in Estonia, but the exact relationship of the court with other institutions has never been researched. The last court included twenty members, with just over half of them ethnic Estonians, if one just considers the ethnic sound of the names (Reference KimmelKimmel 2003).

Before the reform in 1993, the courts employed altogether 83 judges. On January 1, 1996, i.e., about three years after the beginning of the reform, the number of judges had already increased to 206. Of those, 54 had worked as judges before the reform. Many others had previously worked in the criminal justice system as prosecutors. The 29 judges who did not retain their position were disqualified at various stages of the process: Eleven of them did not apply for reappointment, 8 were dismissed by the Supreme Court plenary, and the president refused to appoint another 10. Compared to the overall statistics, the number of dismissals of the former judges was not exceptional: Out of 276 total candidates, the Supreme Court refused to recommend 48 candidates and the president did not nominate a further 38 (data compiled from Riigikohus 1996). Altogether, 75% of the applicants were appointed. Thus many of the judges who wanted to stay in office could do so. This gives us a good variance on the “Soviet experience” of a judge, allowing us to examine whether it makes a difference for case outcomes if a judge was in office before the transition or not.

The reasons for not nominating or appointing certain candidates were not publicly disclosed. We do know that several of the Supreme Court recommendations were denied because no vacancies existed. However, we do not know the exact criteria for choosing among different candidates. The refusal by the president to appoint a candidate was made on a discretionary basis without any justification at all (Reference MarusteMaruste 1994). Even though we cannot identify any discernable bias against former judges or other representatives of the former criminal justice system in this process, it may still be possible that the screening effectively selected certain types of judges—for example, the ones who were expected to behave significantly differently from the rest. Therefore, our analysis cannot determine whether all judges from the previous regime would certainly behave similarly to others. However, we can still test whether they can at least behave similarly to the judges who did not participate in the authoritarian criminal justice system.

Ethnic Minorities and Discrimination in Estonia

The territory of Estonia has for centuries been inhabited mostly by ethnic Estonians, even though the country has rarely been under Estonian rule. In 1922, just after establishing an independent state for the first time, the Estonian population of 1.1 million consisted of 88% Estonians, the biggest minority being Russians, 8% of the population (Reference RaunRaun 2001:271). The ethnic homogeneity, together with effective minority rights protection, remained unchanged until Estonia lost its independence in 1940. However, the situation changed considerably under Soviet rule. In 1989, the Soviet Population Census registered 35% of the population as Russophones (30% of whom were ethnic Russians) living in the territory of Estonia (Reference ZevelevZevelev 2001:96–7). Although the Estonian government officially supported the emigration of Russians to the Russian territory, not many took the opportunity. According to the Estonian Population Census of 2000, ethnic Russians formed 26% of the Estonian population, with the total Russian-speaking minority—including Belorussians, Ukrainians, and a marginal number of nationals of other former Soviet republics—amounting to 30% (Statistical Office of Estonia 2001:9). Thus one still speaks of Russian-speakers, and not ethnic Russians, even though these groups overlap significantly.

Various international organizations and academics have undertaken surveys of the minority situation in Estonia, reporting issues that demonstrate insufficient attention toward the situation of minorities (e.g., UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination 2002; Council of Europe 2001).Footnote 1 Thus, discrimination against the national minority is a topical issue in Estonia, and discrimination through the criminal justice system is highly plausible. Obviously, there is no official policy mandating discrimination against national minorities through the justice system. At the same time, sentencing outcomes demonstrate that the potential for discrimination exists. In 2001, only 41% of prison inmates were ethnic Estonians, although ethnic Estonians committed most of the crimes (Reference Saar, Markina, Ahven, Annist and GinterSaar et al. 2002). The overrepresentation of minorities in the prison population is not surprising (see Reference MauerMauer 1999 for the United States), but it demands explanation. Whether the difference is caused by legally relevant criteria (e.g., non-Estonians commit more serious crimes) or is due to discriminatory sentencing practices is relevant from the point of view of securing basic human rights. Although our focus is not solely on testing sentencing practices regarding the decision whether to incarcerate a defendant (the in/out decision), our analyses are targeted toward detecting different kinds of discrimination in the criminal justice system.

Literature Review

Judiciary in Transition

The literature on judicial behavior in transitional societies is rather limited. The existing political science (and also legal) studies on the judiciary in transition have predominantly discussed the role of supreme or constitutional courts in the transformation process. This includes work on the highest courts in different parts of the world, including Eastern Europe (Reference Randazzo and HerronRandazzo & Herron 2003; Reference BugaricBugaric 2001; Reference Epstein, Knight and ShvetsovaEpstein, Knight, & Shvetsova 2001; Reference SchwartzSchwartz 2000), East Asia (Reference GinsburgGinsburg 2003), South Africa (Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson & Caldeira 2003; Reference WebbWebb 1998), Southern Europe (Reference MagalhãesMagalhães 2003), and Latin America (Reference HelmkeHelmke 2002; Reference SchatzSchatz 1998). Although this literature is useful for understanding the democratic processes in those countries, most such work ignores the fact that supreme courts or specialized constitutional courts handle just a fraction of all cases. Ordinary courts may play a much greater role in the transition process than supreme or constitutional courts, especially because they are closer to the citizens and influence public perception about the fairness and acceptability of the new regime. An empirical study of ordinary courts also gives a broader basis for making generalizations, while a study of supreme or constitutional courts would necessarily remain limited due to the small number of judges and the small number of cases handled.

The work of trial courts during and after transition has received some scholarly attention. Reference MarkovitsMarkovits (1995) gives an observational account of the judicial system, including trial courts, during the East German transition. Hendley has worked extensively on the Russian arbitrazh courts (e.g., Reference HendleyHendley 1999). Reference WidnerWidner (2001) discusses the role the courts play in postconflict transitions in Africa. Reference StotzkyStotzky (1993) presents a compilation of studies on the role of the judiciary in regime transitions in Latin America. Using Peru as a case study, Reference HammergrenHammergren (1997) presents a more general analysis of the role of the judiciary in Latin America. There is plenty of literature on the judges of Nazi Germany in terms of who they were and how they were integrated into the post-World War II German legal profession (e.g., Reference MüllerMüller 1991). Similarly, there is research on the nonintegration of the East German judges into the united German legal profession (Reference MarkovitsMarkovits 1996). Some authors have discussed the politics of judicial reform in ordinary courts (Reference DakoliasDakolias 1995; Reference Rowat, Malik and DakoliasRowat, Haider Malik, & Dakolias 1995; Reference Solomon and FoglesongSolomon & Foglesong 2000; Reference StrohmeyerStrohmeyer 2001). However, the approach is usually either descriptive or policy-oriented, recommending possible solutions to the problems that a country in transition faces. At the same time, the effects of the choices already made during such reforms are not well understood, and the literature does usually not examine the behavior of individual judges but is limited to the output of the whole court. There are also several studies, primarily conducted by lawyers, on “transitional justice,” analyzing the substantive laws dealing with the past (e.g., see Reference TeitelTeitel 2000; Reference KritzKritz 1995; and the reviews by Reference DyzenhausDyzenhaus 2003; Reference VallsValls 2000). Yet this research does not involve analyzing the behavior of the old judges after the regime change.

The literature on the Estonian courts and judicial system is extremely limited, especially concerning studies by political scientists or sociologists. The most interesting essay is written by Reference PettaiPettai (2002/2003), who discusses the outcomes of several ethno-politically relevant cases from the Estonian and Latvian supreme courts. He argues that by deciding both in favor of as well as against minorities, the courts have been balancing “issues of fairness with concerns regarding credibility, since in both countries the courts are new, and they have yet to consolidate their position within the political system” (2002/2003:105). However, more systematic analyses have not been carried out so far.

In sum, there is little theoretical guidance for understanding the behavior of holdover judges in transitional societies. The role of courts as a locus of discrimination against the representatives of the previously dominant but currently minority groups also remains puzzling.

The Effect of Judges' Background Characteristics and Judicial Discrimination

The lack of relevant theorizing and previous empirical studies makes the current analysis an exploration guided by relevant literature developed for advanced democracies. The guidance, however, is anything but firm. Previous research on judicial behavior, mostly based on datasets collected from the United States, is not in agreement as to whether judges' background characteristics are consequential as to how they make their decisions (Reference Ashenfelter, Eisenberg and SchwabAshenfelter, Eisenberg, & Schwab 1995; Reference DixonDixon 1995; Reference Kramer and SteffensmeierKramer & Steffensmeier 1993; Reference Rowland and CarpRowland & Carp 1996; Reference SpohnSpohn 1994; for an earlier review, see Reference Hagan, Bumiller, Blumstein, Cohen, Martin and TonryHagan & Bumiller 1983). For example, Reference Steffensmeier and HebertSteffensmeier and Hebert (1999) show that women tend to be harsher in sentencing decisions. Reference HogarthHogarth (1971) argues that judges with longer working experience impose harsher sentences. The same is considered to apply for older judges (Reference SpohnSpohn 1990). Partisanship is considered to be influential in that Democratic judges in the United States tend to be more liberal than Republican judges (Reference Rowland and CarpRowland & Carp 1996). One of the latest studies also indicates that black judges tend to be harsher in sentencing decisions than white judges (Reference Steffensmeier and BrittSteffensmeier & Britt 2001). However, the results are controversial—Reference Ashenfelter, Eisenberg and SchwabAshenfelter, Eisenberg, and Schwab (1995) conclude, for example, that “[i]n the mass of cases that are filed, even civil rights and prisoner cases, the law—not the judge—dominates the outcomes” (1995:278).

Discrimination in judicial decisionmaking, especially sentencing, has attracted extensive interest again in the United States, mostly from the perspective of race relations. Among the most famous of them is the Baldus study (Reference Baldus, Pulaski and WoodworthBaldus, Pulaski, & Woodworth 1983) on the death penalty, considered by the U.S. Supreme Court in McCleskey v. Kemp (1987). The contemporary literature on sentencing disparities is voluminous. There are plenty of death penalty studies claiming that discrimination does in fact exist (Reference Baldus, Woodworth and PulaskiBaldus, Woodworth, & Pulaski 1990; Reference Baldus, Woodworth, Zuckerman, Weiner and BroffitBaldus et al. 1998). In other sentencing contexts, the research has found mixed results (for reviews, see Reference MustardMustard 2001; Reference WeitzerWeitzer 1996). Modest discrimination has been found during the in/out decision of whether to incarcerate a defendant, as well as in the choice of sentence length (Reference Sampson, Lauritsen and TonrySampson & Lauritsen 1997; Reference SpohnSpohn 2000). However, after controlling for various legitimate grounds for differences in sentences, no systematic bias against minorities has been found (Reference Sampson, Lauritsen and TonrySampson & Lauritsen 1997).

Theoretical Framework

As already stated, two puzzles drive this research. We are, first, interested in whether and how the working experience of a judge in the judicial system of the Communist regime influences his or her decisionmaking as a judge under the new democratic regime. This question has not been systematically researched before. In policy arguments, however, it has been often claimed that “old” judges (and public officials in general) are influenced by their past. This assumption has usually been made by the policy makers. For example, the Estonian judiciary was changed almost completely in 1940 after the Soviet Union took over (Reference Järvelaid and PihlamägiJärvelaid & Pihlamägi 1999). A notable example is the change among the East German judiciary after unification—less than 10% of the judges and prosecutors could retain their offices by 1994 (Reference MarkovitsMarkovits 1996:2271). The dismissal of East German public officials, including judges, was motivated by their perceived incompetence or political unreliability (see Reference QuintQuint [1997] for the reasons behind the change in personnel). Lustration practices in Eastern Europe have been justified not only because of the need of retribution, but also because of the risk that those former officials would pose to the orderly functioning of democracy (Reference OffeOffe 1996:93; Reference LetkiLetki 2002).Footnote 2

We are also interested in determining whether there is any ethnic-based discrimination in judicial decisionmaking. The dependent variable in our study is the case outcome, including the guilty/not guilty decision and the severity of the sentence. These are the most significant and easily observable outcomes of any criminal case.

The Judge's Background and Case Outcomes

In the context of transition, the decision whether to convict or not is an especially interesting issue. The analysis of the determinants of conviction rates is also relevant in the Estonian context as there are no jury trials. The judge decides the conviction or acquittal as well as the sentencing. The prosecutor is an independent public official and not a member of the judicial branch; his or her determinations are not binding on the court. Moreover, the defendant has the right to an attorney, and if he or she cannot afford one, the state appoints one. A formal system of plea bargaining was introduced in 1997, but formerly, confessions before trial were very common. We have excluded those cases from our analysis on conviction decisions.

During the Soviet regime, the acquittal of a person was rare, and was even considered to be a failure of the criminal justice system. This exerted considerable pressure on the judiciary to avoid acquittals (Reference SolomonSolomon 1987). Even though toward the end of the Soviet Union “telephone justice” was not as common as previously and conviction rates dropped (Reference Foglesong and SolomonFoglesong 1997), the pressure on the judges from the Communist Party and the executive branch still existed (Reference Huskey and HuskeyHuskey 1992:224). High conviction rates are considered to be typical among the postcommunist judiciaries and, thus, both Soviet and post-Soviet judges are usually expected to find defendants guilty.

Further, judges from the previous regime may want to appear more loyal to the state than the newly appointed ones. Regime loyalty may not be a unique feature of the judges of the former Soviet Union (see Reference Kritzer, Kritzer and SilbeyKritzer 2003); however, the pressure to appear loyal to the state during the transition may be exacerbated, as the representatives of the previous regime may fear reprisals. For example, Reference HelmkeHelmke (2002) argues that Argentine Supreme Court justices showed considerable independence from the previous regime when it appeared that the regime was changing, presumably in order to please the new regime that was emerging. Thus, deciding in favor of the state can also be interpreted as pledging allegiance to the new regime. This aspect is important for the “old” judges, as their legitimacy is constantly threatened, and winning over the new political elite is crucial to their well-being.Footnote 3 Almost any decision they make may be viewed by politicians as an example of a protest by an old communist against the new regime, whereas similar pressures are not placed on the “new” judges. The newly appointed judges are thus expected to pay more attention to the rights of the individual (the suspect) and be better prepared in their mentality to overturn the prosecutor's case in favor of the suspect. They also feel less pressure to prove their suitability to serve the new regime. These arguments can be summarized into the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a: Judges who have worked in the criminal justice system of the Communist regime are more likely to convict suspects than newly appointed judges.

The Soviet background of some judges may also influence decisions about the harshness of the sentence. The old judges are more constrained by the concern about their image not only in the eyes of the political elite of the new regime but also in the eyes of the public. According to the popular belief, public servants of the old regime carry the ideological baggage of that regime due to their training and working experience. In addition, the public in Eastern European countries has usually supported the screening and possible exclusion of high officials, including judges, for their past activities (see Reference SzczerbiakSzczerbiak [2002] for the data on Poland), as the officials of the former regime are perceived to be less able to adapt to the new environment. One way of gaining legitimacy in the eyes of the public is to appeal to people's immediate concerns. It is generally accepted that the public expects judges to be “tough on crime.”Footnote 4 Due to the increasing crime rates after transition, lack of security in postcommunist countries has become an important concern (see Reference Saar and VetikSaar [1999] for the discussion on Estonia). At the same time, criminal cases receive the most widespread media coverage. The visibility of criminal cases and their prominence in the eyes of the public may encourage old judges to decide against a defendant and to hand harsher sentences in order to advance their public image. The argument is summarized in the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1b: Judges who have worked in the criminal justice system of the Communist regime impose more severe sentences than newly appointed judges.

Discrimination Against Minorities in Sentencing

According to the literature on sentencing, the judge selects between different sentences based on three “focal concerns”: the offender's blameworthiness, the protection of the community, and practical or organizational reasons (Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier & Demuth 2001; Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier, Ulmer, & Kramer 1998). Discrimination against ethnic minorities occurs usually because the past and future behavior of the defendant is associated with the prevalent stereotypes about the ethnic group of the defendant. Thus, if a minority group is associated with crime, the representatives of this group would receive harsher sentences, because they are considered more blameworthy and dangerous to the community than the representatives of the majority. That is, as those prejudices exist among the majority of the population and the political elite, they may also be present among criminal justice officials, including judges. Such prejudices may lead to the belief that minorities are less likely to rehabilitate if a mild sentence is imposed, and that only harsh sentences would have a preventive impact (see Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier, Ulmer, & Kramer 1998). This reasoning applies not only to the sentencing decision, but also to the decision to convict, as evidenced by numerous experimental studies (Reference Sommers and EllsworthSommers & Ellsworth 2000).

The stereotypes of Russians among Estonians are certainly not positive. Reference Kolstø, Melberg and KolstøKolstø and Melberg (2002:53–4) report the results of a mass survey that asked ethnic Estonians to compare themselves to ethnic Russians on twelve different characterizations. They found that Estonians tended to “attribute good qualities to ethnic Estonians and reserve the negative ones for Russians” (2002:53–4). Among other things, Estonians perceived Russians to be less trustworthy and more easily drawn into conflicts.

Another aspect of the postcommunist transition may breed discrimination in many Eastern European countries: During the Soviet regime, the Russian-speaking population, and not locals, often occupied important political and judicial positions. For example, after 1950, the two top positions of the Estonian Communist Party were always occupied by ethnic Russians (Reference RaunRaun 2001:191), and many ethnic Russians occupied important positions in the criminal justice system (Reference Järvelaid and PihlamägiJärvelaid & Pihlamägi 1999).Footnote 5 Moreover, in Estonia, 73% of ethnic Estonians partly or completely agree with the claim that they as an ethnic group were oppressed in the Soviet Union (Reference Kolstø, Melberg and KolstøKolstø & Melberg 2002:45). It is, thus, reasonable to argue that after the transition, the ethnic majority would seek “revenge” against the representatives of the former oppressive regime. Furthermore, at least 48% of Russians living in Estonia believe that Estonians want to take revenge on them (Reference Kolstø, Melberg and KolstøKolstø & Melberg 2002:43). Whereas official policies are under strict scrutiny from various international organizations, informal policies and actions, including criminal justice practices, can most effectively be used to seek such revenge. The arguments elaborated allow concluding with the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a: Minority suspects are more likely to be convicted than majority suspects.

Hypothesis 2b: Minority defendants are expected to receive harsher sentences than their majority counterparts.

In addition to the Soviet background of the judge and the ethnicity of the suspect or offender, other variables may account for the variation in judicial decisionmaking. These include the factors foreseen by laws that limit the discretion of judges, such as the characteristics of the crime and the background of the criminal (Reference Steffensmeier and BrittSteffensmeier & Britt 2001; Reference Ashenfelter, Eisenberg and SchwabAshenfelter, Eisenberg, & Schwab 1995). According to the Estonian criminal code, the judges must consider the offender's prior criminal record and/or voluntary confession and regret in determining the sentence. The existence of a prior criminal record should, thus, increase, and the voluntary confession decrease the severity of the sentence.Footnote 6 Other illegitimate factors may determine the sentence. Studies have usually shown that women receive more lenient sentences (Reference AlbonettiAlbonetti 1998; Reference Simon and LandisSimon & Landis 1991; Reference Steffensmeier, Kramer and StreifelSteffensmeier, Kramer, & Streifel 1993; Reference Nagel and JohnsonNagel & Johnson 1994) and that less-educated criminals are often viewed as less capable of understanding the consequences of their crimes and, thus, in need of harsher sentences.

Unfortunately, we cannot include a potentially influential variable—the ethnic background of the judge—into our analysis because we cannot determine the ethnicity of the judge with certainty, as this information is not provided in the official records. One option would be to consider judges' names and code those with Russian-sounding names as Russians. There are two problems related to such coding, however. First, although Estonian and Russian names are very distinct, not everyone having a Russian name is necessarily Russian and vice versa. Second, our dataset includes only four judges with Russian-sounding names (who made in total forty-five decisions out of 749), allowing for very little variance on this variable. We still performed two alternative analyses to those described below. For one of those alternative estimations, we included a dummy variable for decisions by judges with Russian-sounding names, while for the other we excluded all decisions by those judges. The correlation coefficient between the dummy variable measuring judge ethnicity and the one measuring judicial experience under previous regime was only 0.27, considerably below the level at which multicollinearity becomes a concern. The control variable for Russian judges did not have a significant coefficient, and the substantive results of each analysis did not differ from the ones presented below.

Methods and Data

Our data comprise a sample of decisions of trial-level judges for the years 1995 through 2001. We obtained the decisions from the Estonian Supreme Court, which collected copies of the opinions of the trial courts under an informal agreement. For these six years, we selected all cases involving embezzlement. There are both practical and theoretical justifications for such a decision. The total number of embezzlement cases for the period covered is manageable, so that we could include the universe of all cases. This assures that our total sample does not suffer from a selection bias. Further, by concentrating on one type of crime only, we could avoid comparing the severity of punishment for crimes with significantly different levels of seriousness. Such comparison would have been meaningful if we had been able to code a considerably large number of crimes of different type—a task too difficult to accomplish for two researchers. Further, our research questions require the range of sentences to vary. In order to achieve this, we had to consider a complex crime that usually allows for more variation than simple crimes on the decision about guilt. Indeed, the average rate of acquittal in Estonian courts is 3% (Ministry of Justice 2001), compared with 8% in the case of embezzlements. Unfortunately, there are no official data on acquittal rates when charges are contested (in our sample, the rate is 35%). We acknowledge that this makes embezzlement not a totally representative crime for all crimes handled by the Estonian courts. Yet, to a certain extent, such nonrepresentativeness is also desired. That is, the embezzlement cases constitute the “hard” cases for a part of our theory: The effect of judge characteristics on this type of crime may be more pronounced than on other types of crime, as embezzlement—a crime against socialist property—was a serious crime during Soviet rule (Reference ŁośŁoś 1988), especially so toward the end of the Soviet era, when economic performance declined (Reference SmithSmith 1996:142). The perception of the seriousness of embezzlement cases may compel the old judges to be stricter about conviction and to hand out harsher sentences. However, if we find that the Soviet background of a judge has no effect on decisionmaking in embezzlement cases, there is less reason to believe that it has any significant effect on judicial decisionmaking concerning other types of crime.

Further, we can see no theoretical reason for why embezzlement cases would not be representative for the purposes of determining the effect of the other variable of interest: the ethnic background of the defendant. One the one hand, it is indeed possible to argue that negative ethnic stereotypes may be associated not so much with white-collar crimes but more with violent crimes, as ethnic Russians are viewed as being more easily drawn into conflicts. However, the fact that Russians dominated the political and economic spheres before transition would make this group especially suspicious regarding their economic activities after transition. Ethnic Estonians seeking revenge for the corrupt activities of high Communist Party officials would invoke harsher sentences on ethnic Russians.

Our analysis would be impossible if the judges possessed no discretion in determining the sentences or if the possible range of sentences was limited, with no variation in our dependent variables. Fortunately, the Estonian criminal justice system allocates much discretion to the judge in determining the sentence. Sentences are usually limited only by statutory lower and upper bounds. A list of factors is given in order to help the judge choose the appropriate sentence within the boundaries. However, there are no sentencing grids, similar to the United States, and therefore, the list of sentencing factors does not limit discretion significantly. In exceptional cases, the judge may even choose a sentence below the lower limit. In many cases, the judge may also choose between a fine and a prison sentence. The mandated sentences for the embezzlement are a fine or a prison sentence of up to four years for little damage (less than 100 times the monthly minimum wage), and a prison sentence from three to eight years for greater damage. Within these limits, there are considerable differences in the decision outcomes (see the Appendix for the descriptive statistics).

The cases and decisions' reasoning were not centrally filed before 1995 and thus are not available for coding. However, the universe of a specific type of cases for the six years studied—involving altogether 749 suspects—gives us a reasonable basis for making inferences. As stated, we coded most variables included in the analyses from the reasoning of the trial court decisions. The data about the background information of judges were coded from Riigikohus (1996) and the personnel files of the Ministry of Justice.

Operationalization of Variables

In order to measure decision outcome, we coded four different variables. The first of these measures captures the determination of guilt. As argued above, we believe that it is a valid indicator of the harshness of a judge, showing the willingness of the judge to protect individuals against the state. That is, holding the legal provisions constant, if a judge overturned the prosecutor's case and acquitted the suspect, he or she is supportive of individual rights against the arbitrary intervention by the state. The measure for the determination of guilt is binary, coded 1 when the suspect is found guilty and 0 otherwise.

The severity of punishment is measured by three different indicators: the in/out decision, the length of incarceration, and the amount of the fine. The first of these measures indicates whether or not the prison sentence was suspended. It is coded 0 if the judge chose the punishment by fine and also if the prison sentence was suspended. Thus, only those cases where the convict actually faced imprisonment were coded 1.

In Estonia, even if the sentence were suspended, the length of imprisonment would still be determined in the same decision in years and months. If the offender were to break the parole rules, the length of imprisonment would be automatically determined according to the previous decision. Thus, we also coded a variable capturing the length of incarceration as stated in the decisions (regardless of whether it was actually administered). Certain caution must be taken about using this measure, though, as in the overwhelming majority of cases probation was administered instead of actual incarceration. Thus, it may be that as the judge was aware that the convict would actually not face incarceration, the length of punishment may appear not as a real but only as a symbolic punishment. However, we believe that differences in the length of incarceration, even when the sentence was not in fact administered, should be informative for detecting discrimination. Indeed, given that various international organizations and domestic actors constrain judges by scrutinizing the easily observable aspects of their behavior, much actual discrimination may take a symbolic form. The length of incarceration is measured in months coded from the court decisions.

The amount of the fine is yet another indication of the severity of punishment. The variable is measured in FY 1995 constant Estonian kroons, coded from the court decisions and recalculated based on the official statistics of the Estonian Statistical Office. In Estonia, the amount of a fine is not dependent on the offender's income.

The two independent variables of interest—the defendant's nationality and the Soviet experience—are measured by dummy variables. We coded the Estonian defendants as 0 and the rest of the defendants as 1. As the court decisions contained explicit information on the ethnicity, we did not have to infer the ethnicity from the names of the defendants. The overwhelming majority of non-Estonians were Russians or Russian-speaking people.

The Soviet experience variable was coded 1 for those judges that had served as judges or prosecutors during the previous regime and 0 for judges without such experience. A note is in order about such measurement. One might argue that any binary classification of judges to those with Soviet experience and those without one is arbitrary, because even if a judge is nominated or appointed to office some years after the regime change, his or her previous experience and education dates back to the Soviet era. However, we expect that the experience of actively participating in the criminal justice system of the previous regime is more consequential to the behavior and attitudes of judges than just having lived and studied under that regime.

The measurement of the control variables is explained in the Appendix, which also presents the descriptive statistics for all variables included in the analyses.Footnote 7 Certain variables have some missing values, which is why the total number of cases does not always add up to 749.

Analysis and Results

We estimated four different models according to the dependent variable used. As we have multiple observations for individual judges, these observations are not independent. Thus, we used the Huber-White/sandwich estimator of the variance instead of the conventional MLE variance estimator within the clusters of observations by judge for all four models. The first model uses logit estimation to predict the determination of guilt. Excluding cases where the suspects confessed their crime, 156 decisions are included in the analysis. We excluded the cases where the suspect confessed, because the overwhelming majority of confessions in Estonia were made before the court proceedings, thus eliminating the potential influence of the judge over such cases.

As presented in Table 1, the logit model is significant with a chi-squared of 17.212 and a pseudo-R2 of 0.146. The full model is able to correctly predict 69% of the time whether the suspect is found guilty or not. This is a 5% improvement in the prediction over the model that does not include any of the independent variables. With regard to the conventional indicator of variable importance—the level of statistical significance—only one variable exceeds the significance level. We found that the defendant's sex has a significant effect on the determination of guilt: The odds of female suspects being found guilty are estimated to be 4.9 times as high as those of male suspects, other things being equal. This result may reflect the possibility that women commit less sophisticated and more easily detectable crimes than men.

Table 1. Logit Model Predicting Conviction Rates

NOTE: Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.001.

Most important, however, neither defendant nationality nor the Soviet experience of the judge has a significant effect on the determination of guilt. No significant relationship between a decision on conviction and suspect nationality supports the argument about nondiscrimination in judicial decisionmaking. Further, we find no support for the argument that there is a significant difference between the old and the new judges in their decisions about the determination of guilt.

Table 2 presents the results for the logit model predicting the probability of actual incarceration. The analysis excludes the cases where the defendant was not found guilty. Excluding also the observations with missing values, the sample size for this analysis is 580. The overall model is significant with a chi-squared of 53.847 and the pseudo-R2 of 0.134. However, as was the case with the determination of guilt, the probability of actual incarceration is independent of the Soviet experience of the judge and the ethnicity of the defendant. The only two significant predictors of the likelihood of actual incarceration are the level of education and the previous criminal record of the defendant. That is, defendants having secondary and higher education are less likely to face actual imprisonment than defendants with primary education only, while the previous criminal record of the defendant increases the probability of imprisonment significantly.

Table 2. Logit Model Predicting Actual Incarceration

NOTE: Robust standard errors in parentheses, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

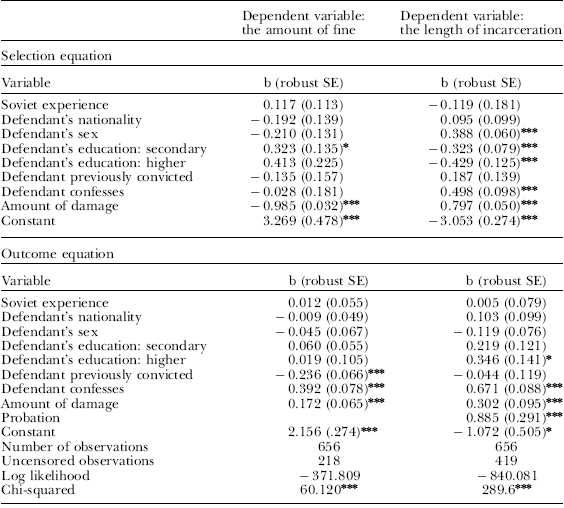

The next two models estimate the severity of punishment: the amount of the fine and the length of incarceration, respectively. The nature of these two dependent variables creates a potential for selection bias, as not all decisions impose a fine, and those that do cannot impose an incarceration. The result of this problem is that a simple ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression of the amount of fine or the length of incarceration on a set of predictors may lead to downward-biased estimates. As is standard with these types of data, Heckman modeling was used to correct for the selection bias (Reference Peterson and HaganPeterson & Hagan 1984). The Heckman procedure would account for the propensity to impose a fine (or imprisonment) when estimating the effect of the set of independent variables on the amount of the fine (or the length of imprisonment).Footnote 8 Both the amount of the fine and the length of incarceration are highly skewed, with small fines and short punishments being more frequent than big fines and lengthy punishments. Thus, as is common in the sentencing research (Reference AlbonettiAlbonetti 1997; Reference Weisbud, Wheeler, Waring and BodeWeisbud et al. 1991), we used the natural log of both variables in the analysis.Footnote 9

Table 3 presents the results for both the analysis of the amount of the fine (Column 1) and that of the length of incarceration (Column 2). The chi-squared and log likelihood statistics indicate a good fit for both models. The two models are also rather consistent in terms of the significant explanatory variables associated with the severity of punishment. This is comforting given the concerns about the appropriateness of the length of incarceration measure discussed above. That is, as the two alternative models behave in similar manner, we can be somewhat more confident that both of these measures of the dependent variable are capturing a similar underlying concept of the severity of punishment in either model.

Table 3. Heckman Models Predicting the Determinants of the Severity of Punishment

NOTE: Robust standard errors in parentheses,

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01,

*** p < 0.001.

In terms of substantive findings, the null hypothesis that the defendant's nationality and the severity of punishment are related cannot be rejected based on either estimation. Similarly, the working experience within the Soviet judicial system does not appear to be a significant predictor of the severity of punishment in both models. Furthermore, neither of these variables is a significant predictor in the selection model as well. That is, the defendant's nationality appears to have no effect on the decision of whether the punishment will be in the form of a fine or incarceration. This decision does also not depend on whether the decision is made by an old or a new judge. In other words, we found no evidence of discrimination based on nationality in court decisions and no significant difference between judges with experience under different regimes. The consistency of these findings across models increases the confidence in the empirical validity of the nondiscrimination claim.

Among the control variables, the most significant predictors of the severity of punishment in both models are, intuitively as well as statistically, the amount of damage and the prior conviction of the defendant. The increase in these variables is associated with an increase in the severity of punishment. A guilty plea is associated with smaller fines, while it has no significant effect on the length of incarceration. There is a weak effect of the defendant's level of education on the length of incarceration, with those having higher education receiving lengthier sentences.

Overall, none of the four analyses performed provide evidence of any significant discrimination based on the nationality of the defendant in judicial decisionmaking. Non-Estonians are not more likely to be convicted than Estonians, and minorities do not face harsher sentences once convicted. Further, none of the models supports the claim that there are significant differences between the decisionmaking of old and new judges. Rather, the empirical findings presented here allow the conclusion that in their most important decisions—the determination of guilt and of the severity of punishment—former Soviet judges are not different from the new generation of judges who have no experience in the governing structures of an authoritarian regime.

Conclusion

The current study was an exploration of the judicial behavior in Estonia after transition. Our empirical tests did not find any differences in the behavior of judges with working experience in the judicial system of the previous regime as compared with judges without such experience. In addition, we found no evidence that the Russian minority, who used to be the dominant group just a decade before, is treated differently than the Estonian majority is treated by the Estonian judicial system. However, our study is limited by the focus on one type of crime in one country only. Therefore, our findings about the impartiality of the judicial system can form only a basis for further theorizing on and empirical investigation of the determinants of judicial behavior in nascent democracies. As the Estonian situation is similar to many other transitional countries, our work does have some general implications.

The finding of suitable court personnel is a problem faced by all transitional countries. Those judges who worked as a part of the totalitarian regime are generally not perceived as suitable for the fulfillment of judicial duties in the democratic regime. Our finding that the Soviet-era criminal justice system experience in itself is not a significant determinant of judicial behavior in transitional period leaves room for alternative explanations such as the personal characteristics of judges and their knowledge and competence. Our study indicates that in order to establish a qualitatively different judicial system under a new regime, it is not necessary to dismiss most of the old judges. Replacing the existing judiciary in toto appears much less relevant than, for example, investing in the education and training of judges as well as in the resources of courts.

Discrimination against ethnic minorities is also a problem facing many transitional countries. The activities of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) High Commissioner for National Minorities offer ample proof that discrimination is a serious issue throughout Central and Eastern Europe (Reference KempKemp 2001). Moreover, like Estonia, most transitional countries are or were under international surveillance with regard to their official policies toward minorities. Our analysis supports the argument that the transitional judiciary can be an independent actor established to fairly determine case outcomes and not a tool in the service of promoting the fortunes or agenda of the new ethnic “in” group. The judiciary can be viewed as an institution where ethnic minorities may claim equal rights with the majority. Further studies in different national settings are necessary to make firmer generalizations. However, findings that indicate no discrimination could also be used in informing the public, especially minorities, about the possibilities to find justice in the courts. The findings would refute the disappointment of minorities in new political institutions, at least regarding one of them.

Further work on judicial behavior in transition would be highly valuable. People's trust in the courts and the judicial system are important preconditions for regime stability, and the impartiality of courts is essential for securing this trust (Reference Rothstein and StolleRothstein & Stolle 2002). The better we understand the determinants of judicial decisionmaking, the easier it is to create necessary institutions to ensure the fairness of the judicial system.

Appendix

Description of Control Variables

Descriptive Statistics and Frequencies for All Variables in the Analysis