Article contents

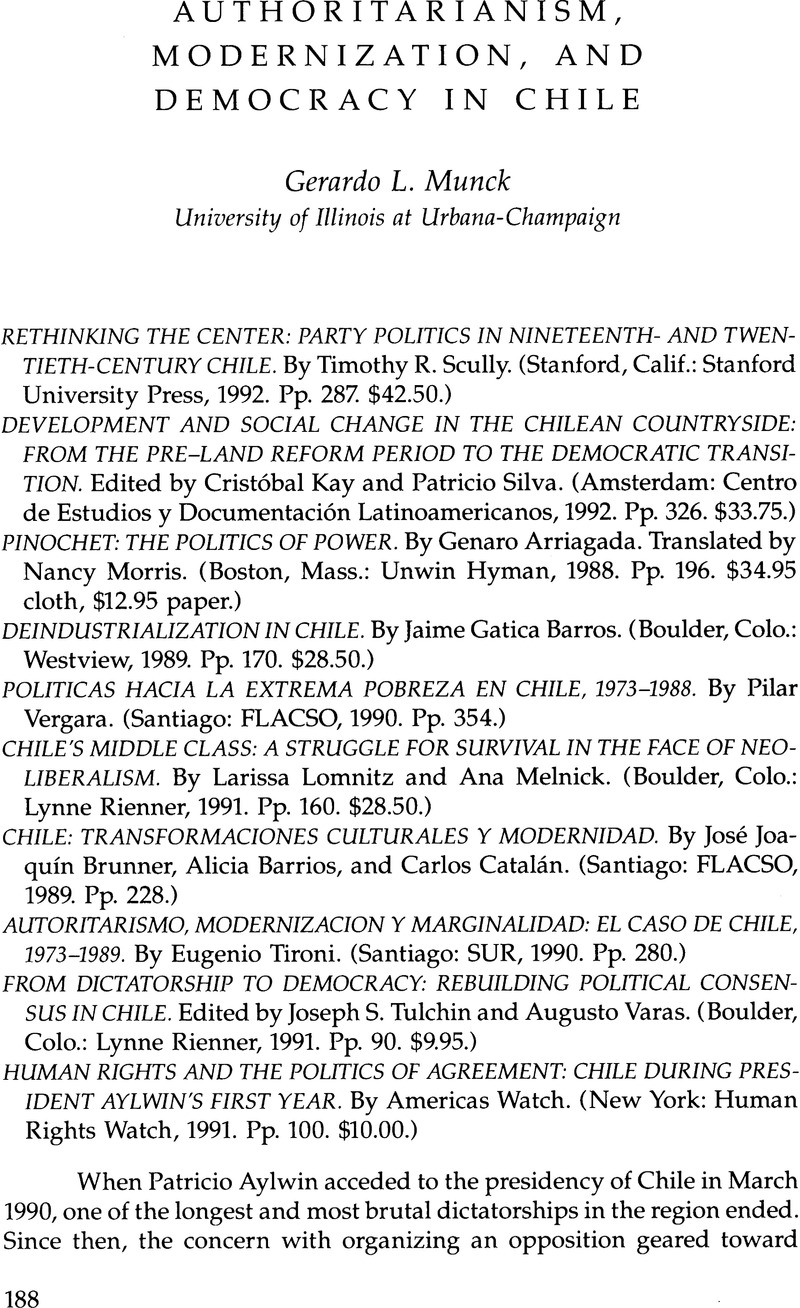

Authoritarianism, Modernization, and Democracy in Chile

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1994 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. See Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan, “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction,” in Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives, edited by Lipset and Rokkan (New York: Free Press, 1967); and Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991).

2. Some of the key previous works include Arturo Valenzuela, The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Chile (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978); Paul W. Drake, Socialism and Populism in Chile, 1932–1953 (Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1978); and J. Samuel Valenzuela, Democratización vía reforma: la expansión del sufragio en Chile (Buenos Aires: Ediciones del IDES, 1985).

3. This reading of the evolution of the Chilean party system also modifies the views presented by Ruth Collier and David Collier. Scully goes beyond their focus in Shaping the Political Arena in assessing the urban labor cleavage, and he presents a more nuanced view of how new cleavages intersect with the old ones (pp. 172, 182–84).

4. In referring to the causes of the 1973 coup, Tironi's book strongly emphasizes economic tensions in a manner that closely follows O'Donneirs 1973 argument. See Guillermo O'Donnell, Modernization and Bureaucratic-Authoritarianism: Studies in South American Politics (Berkeley: Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, 1973). Tironi does not cite this classic work, drawing instead on the work of the French regulation school (pp. 126–29). While he does refer to Valenzuela's The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Chile, his invocation of the importance of institutions seems tacked on to the economic reasoning somewhat as an afterthought.

5. Ibid.

6. Peter Evans, “The State as Problem and Solution: Predation, Embedded Autonomy, and Structural Change,” in The Politics of Economic Adjustment: International Constraints, Distributive Conflicts, and the State, edited by Stephan Haggard and Robert R. Kaufman, 139–81 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1992).

7. Taking into account the drastic reductions in gross national product during the crises in 1975 and 1981–1983, however, the growth rate over the entire seventeen years that Pinochet held power averaged only 3 percent per year.

8. Seymour Lipset, Kyoung Ryung Seong, and John Carlos Torre, “A Comparative Analysis of the Social Requisites of Democracy,” International Social Science Journal, no. 136 (May 1993):155–75.

9. Tironi draws on Touraine's definition, in which social movements are actors linked to the functioning of a society but not to its change (pp. 21, 32, 18, 20). Most readers would ask for some “unpacking” of this definition.

10. Countering economic explanations that locate the root of this cultural change in the direct impact of the 1981–1983 economic crisis, Brunner et al. view the protests themselves as bringing about the “reintroduction of the principle of politics in civil society,” that is, as “a principle affecting everyday mass culture” (p. 94). Thus if the economic crisis is perceived as partly enabling this change, the emergence of social actors organized in opposition to the government is conceptualized in terms more like those emphasizing the loss of fear than like those who consider economic hard times as the primary explanation. Like wise, Tironi advances a critique of economic explanations of the protests and the subse quent transition. He states flatly that research links violent protest to “factors associated with the instability of the political system” and not with “socioeconomic variables” (pp. 206–7, 225–27). At other points, however, Tironi stresses the importance of economic factors, much as he does in his argument concerning the 1973 coup, viewing the economic crisis as leading more or less to the political opening and the protests (pp. 145–46, 27, 22). This confusion arises from Tironi's lack of explicit discussion of the economic theories that he draws on as well as from the need for clarification of the links between economic and social categories.

11. Some of the main academic sources on the transition process include Manuel Antonio Garretón, Reconstruir la política: transición y consolidación en Chile (Santiago: Andante, 1987); The Struggle for Democracy in Chile, 1982–1990, edited by Paul Drake and Iván Jaksic (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991); and Guillermo Campero and René Cortázar, “Actores sociales y la transición a la democracia en Chile,” Colección Estudios CIEPLAN, no. 25 (1988):115–58.

12. The key legacies included Pinochet's right to remain commander in chief of the army for eight more years and thereafter as senator for life, the presence of nine appointed senators, a national security council with strong powers and military representation, and a packed supreme court. A series of other preemptive and confining measures were taken by the Pinochet government in the year after defeat in the 1988 plebiscite, including laws affecting the central bank, elections, and television as well as appointments within the armed forces and military budgets. Some of the more restrictive aspects of the Constitution of 1980 were softened through a series of amendments approved in a July 1989 plebiscite. The constitutional reforms flexibilized the mechanisms for reforming the constitution, reduced the mandate of the first president to four years, diminished the importance of the designated senators, changed the composition and powers of the national security council to diminish the tutelary role of the military, and rescinded the proscription of the Communist party.

13. For the full report, see the Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation, 2 vols. (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1993).

14. In the most important human rights prosecution to date, retired General Manuel Contreras, former head of the secret police (the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional, or DINA), was put on trial in late 1992.

15. The need for change is also pressing regarding a series of undemocratic features of the Constitution of 1980, some of which pertain to civil-military relations. One important step was taken in early 1992, when a municipal and regional reform passed by the congress led to the municipal elections in June 1992, the first in twenty years. That same month, the government introduced a reform package to reestablish democratic control over the armed forces, eliminate the non-elected senators, loosen military control of the national security council, and make the electoral system more representative and proportional. Passage of these constitutional reforms will require the support of the right-wing parties, given their control of the senate. But because of the results of the municipal elections (the government parties received 53.5 percent of the vote compared with less than 30 percent for the right-wing parties, the Unión Democrática Independiente and Renovación Nacional), the right now appears determined to block the reforms. If they succeed, then the vestiges of the authoritarian constitution will have to be tackled by the winners of the presidential and parliamentary elections in December 1993. On the proposed constitutional reforms, see Ignacio Walker, “La reforma constitutional,” Mensaje (Santiago), no. 410 (July 1992):213–15.

16. Weffort, “Novas Democracias, Qué Democracias? Lua Nova, no. 27 (1992):5–30, 23.

17. Evans, “The State as Problem and Solution,” 176–81.

18. Paul Drake, “Urban Labour Movements under Authoritarian Capitalism in the Southern Cone and Brazil, 1964–1983,” in The Urbanization of the Third World, edited by Josef Gugler, 366–98 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 388.

19. Ibid.

20. Juan Linz, “Change and Continuity in the Nature of Contemporary Democracies,” in Reexamining Democracy, edited by Gary Marks and Larry Diamond, 182–207 (Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage, 1992), esp. 182–87; and Wanderley Guillerme dos Santos, “El siglo de Michels: competencia oligopólica, lógica autoritaria y transición en América Latina,” in Muerte y resurección: los partidos políticos en el autoritarismo y las transiciones en el Cono Sur, edited by Marcelo Cavarozzi and Manuel Antonio Garretón, 469–522 (Santiago: FLACSO, 1989).

21. Laurence Whitehead, “The Alternatives to Liberal Democracy: A Latin American Perspective,” in Prospects for Democracy, edited by David Held, a special issue of Political Studies 40 (1992):146–59, 154.

22. O'Donnell, Delegative Democracy? Kellogg Working Paper no. 172 (Notre Dame, Ind.: Kellogg Institute for International Studies, University of Notre Dame, 1992). See also Whitehead, “Alternatives to Liberal Democracy,” 151.

23. For a useful discussion, see Stephan Haggard and Robert Kaufman, “Economic Adjustment and the Prospects of Democracy,” in Politics of Economic Adjustment, edited by Haggard and Kaufman, 319–50.

- 2

- Cited by