Article contents

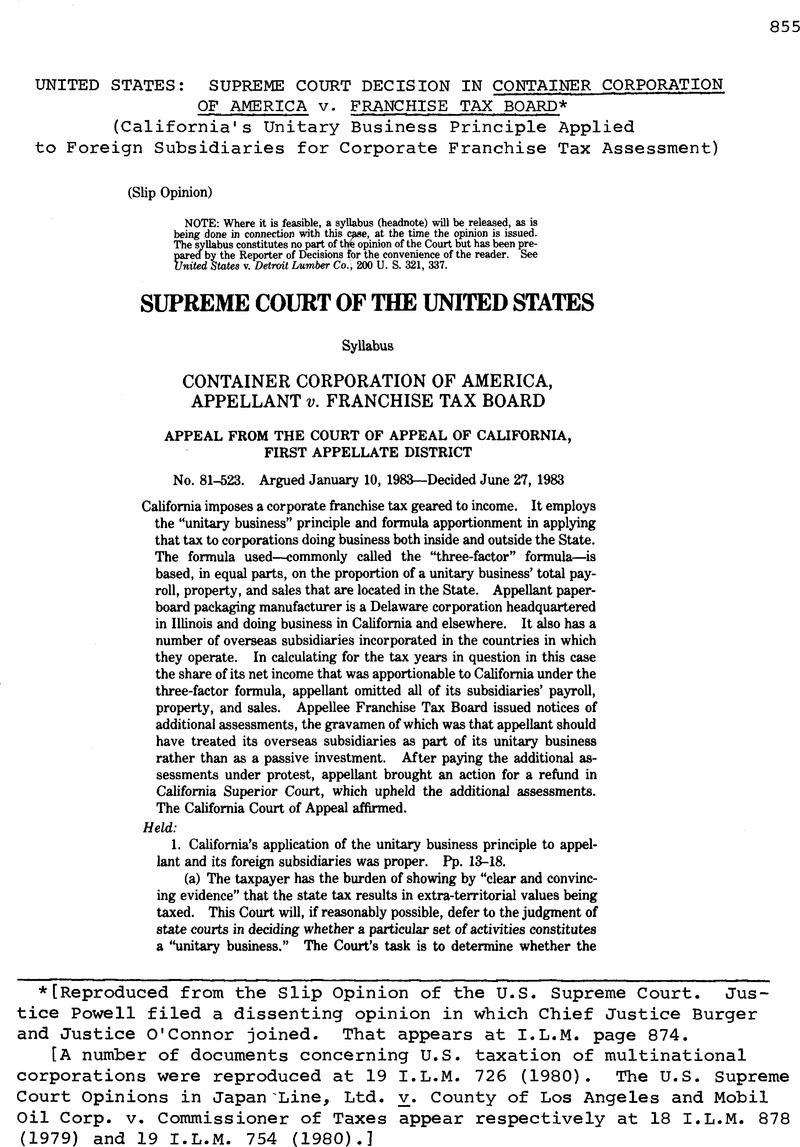

United States: Supreme Court Decision in Container Corporation of America v. Franchise Tax Board*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1983

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the Slip Opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice Powell filed a dissenting opinion in which Chief Justice Burger and Justice O'Connor joined. That appears at I.L.M. page 874.

[A number of documents concerning U.S. taxation of multinational corporations were reproduced at 19 I.L.M. 726 (1980). The U.S. Supreme Court Opinions in Japan Line, Ltd. v. County of Los Angeles and Mobil Oil Corp. v. Commissioner of Taxes appear respectively at 18 I.L.M. 878 (1979) and 19 I.L.M. 754 (1980).]

References

1 Certain forms of non-business income, such as dividends, are allocated on the basis of the taxpayer’s commercial domicile. Other forms of nonbusiness income, such as capital gains on sales of real property, are allocated on the basis of situs. See Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code Ann.

§§ 25123-25127 (West 1979).

2 See generally Honolulu Oil Corp. v. Franchise Tax Board, 60 Cal. 2d 417, 386 P. 2d 40 (1963); Superior Oil Corp. v. Franchise Tax Board, 60 Cal. 2d 406, 386 P. 2d 33 (1963).

3 See the opinion of the California Court of Appeal in this case, 117 Cal. App. 3d 988, 990-991, 993-995 (1982). See also Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code Ann. § 25137 (West 1979) (allowing for separate accounting or other alternative methods of apportionment when total formula apportionment would “not fairly represent the extent of the taxpayer’s business activity in the state”).

4 We note that the Uniform Act does not speak to this question one way or the other.

5 See also Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code Ann. §25105 (West 1979) (denning “ownership or control”). A necessary corollary of the California approach, of course, is that inter-corporate dividends in a unitary business not be included in gross income, since such inclusion would result in double-counting of a portion of the subsidiary’s income (first as income attributed to the unitary business, and second as dividend income to the parent). See § 25106.

Some States, it should bevuoted, have adopted a hybrid approach. In Mobil itself, for example, a non-domiciliary State invoked a unitary business justification to include an apportioned share of certain corporate dividends in the gross income of the taxpayer, but did not require a combined return and combined apportionment. The Court in Mobil held that the taxpayer’s objection to this approach had not been properly raised in the state proceedings. 445 U. S., at 441, n. 15. Justice Stevens, however, reached the merits, stating in part: “Either Mobil’s worldwide ‘petroleum enterprise’ is all part of one unitary business, or it is not; if it is, Vermont must evaluate the entire enterprise in a consistent manner.” Id., at 461 (citation omitted). See id., at 462 (Stevens, J., dissenting) (outlining alternative approaches available to State); cf. The Supreme Court, 1981 Term, 96 Har v. L. Rev. 62, 93-96 (1982).

6 See generally G.A.O. Report to the Chairman, House Committee on Ways and Means: Key Issues Affecting State Taxation of Multijurisdictional Corporate Income Need Resolving 31 (1982).

7 Mobil did, in fact, involve income from foreign subsidiaries, but that fact was of little importance to the case for two reasons. First, as discussed in n. 5, supra, the State in that case included dividends from the subsidiaries to the parent in its calculation of the parent’s apportionable taxable income, but did not include the underlying income of the subsidiaries themselves. Second, the taxpayer in that case conceded that the dividends could be taxed somewhere in the United States, so the actual issue before the Court was merely whether a particular State could be barred from imposing some portion of that tax. See 445 U. S., at 447.

8 There were a number of reasons for appellant’s relatively hands-off attitude toward the management of its subsidiaries. First, it comported with the company’s general management philosophy emphasizing local responsibility and accountability; in this respect, the treatment of the foreign subsidiaries was similar to the organization of appellant’s domestic geographical divisions. Second, it reflected the fact that the packaging industry, like the advertising industry to which it is closely related, is highly sensitive to differences in consumer habits and economic development among different nations, and therefore requires a good dose of local expertise to be successful. Third, appellant’s policy was designed to appeal to the sensibilities of local customers and governments.

9 There was also a certain spill-over of good-will between appellant and its subsidiaries; that is, appellant’s customers who had overseas needs would on occasion ask appellant’s sales representatives to recommend foreign firms, and where possible, the representatives would refer the customers to appellant’s subsidiaries. In at least one instance, appellant became involved in the actual negotiation of a contract between a customer and a foreign subsidiary.

10 After the notices of additional tax, there followed a series of further adjustments, payments, claims for refunds, and assessments, whose combined effect was to render the figures outlined in text more illustrative than real as descriptions of the present claims of the parties with regard to appellant’s total tax liability. These subsequent events, however, did not concern the legal issues raised in this case, nor did they remove either party’s financial stake in the resolution of those issues. We therefore disregard them for the sake of simplicity.

11

See Exhibit A-7 to Stipulation; Record 36, 76, 77, 79, 104, 126.

12 According to the notices, appellant’s actual tax obligations were as follows:

See Exhibit A-7 to Stipulation; Record 76, 77, 79.

13 This approach is, of course, quite different from the one we follow in certain other constitutional contexts. See, e. g., Brooks v. Florida, 389 U. S. 413 (1967); New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254, 285 (1964).

14 It should also go without saying that not every claim that a state court erred in making a unitary business finding will pose a substantial federal question in the first place.

15 ASARCO and F.W. Woolworth are-consistent with this standard of review. ASARCO involved a claim that a parent and certain of its partial subsidiaries, in which it held either minority interests or bare majority interests, were part of the same unitary business. The state supreme court upheld the claim. We concluded, relying on factual findings made by the state courts, that a unitary business finding was impermissible because the partial subsidiaries were not realistically subject to even minimal control by ASARCO, and were therefore passive investments in the most basic sense of the term. 458 U. S., at. We held specifically that to accept the state’s theory of the case would not only constitute a misapplication of the unitary business concept, but would “destroy” the concept entirely. Id., at.

F.W. Woolworth was a much closer case, involving one partially-owned and three wholly-owned subsidiaries. We examined the evidence in some detail, and reversed the state court’s unitary business finding, but only after concluding that the state court had made specific and crucial legal errors, not merely in the conclusions it drew, but in the legal standard it applied in analyzing the case. 458 U. S., at.

19 In any event, although potential control is, as we said in F.W. Woolworth, not “dispositive” of the unitary business issue, 458 U. S., at (emphasis added), it is relevant, both to whether or not the components of the purported unitary business share that degree of common ownership which is a prerequisite to a finding of unitariness, and also to whether there might exist a degree of implicit control sufficient to render the parent and the subsidiary an integrated enterprise.

17 As we state supra, at 6-7, there is a wide range of constitutionally acceptable variations on the unitary business theme. Thus, a leading scholar has suggested that a “flow of goods” requirement would provide a reasonable and workable bright-line test for unitary business, see Hellerstein, Recent Developments in State Tax Apportionment and the Circumscription of Unitary Business, 21 Nat’l Tax J. 487, 501-502 (1968); Hellerstein, , Allocation and Apportionment of Dividends and the Delineation of the Unitary Business, 27 Tax Notes 155 (1981)Google Scholar, and some state courts have adopted such a test, see, e. g., Commonwealth v. ACF Industries, Inc., 441 Pa. 129, 271 A. 2d 273 (1970). But see, e. g., McLure, , Operational Interdependence Is Not The Appropriate ‘Bright Line Test’ of A Unitary Business—At Least Not Now, 28 Tax Notes 107 (1983)Google Scholar. However sensible such a test may be as a policy matter, however, we see no reason to impose it on all the States as a requirement of constitutional law. Cf. Wisconsin v. J.C. Penney Co., 311 U. S. 435, 445 (1940).

18 See n. 15, supra. See also, e. g., F.W. Woolworth, supra, at (“no phase of any subsidiary’s business was integrated with the parent’s.”), (undisputed testimony stated that each subsidiary made business decisions independent of parent), (“each subsidiary was responsible for obtaining its own financing from sources other than the parent”), (“With one possible exception, none of the subsidiaries’ officers during the year in question was a current or former employee of the parent.”) (footnote omitted).

19 Two of the factors relied on by the state court deserve particular mention. The first of these is the flow of capital resources from appellant to its subsidiaries through loans and loan guarantees. There is no indication that any of these capital transactions were conducted at arm’s-length, and the resulting flow of value is obvious. As we made clear in another context in Corn Products Co. v. Commissioner, 350 U. S. 46, 50-53 (1955), capital transactions can serve either an investment function or an operational function. In this case, appellant’s loans and loan guarantees were clearly part of an effort to insure that “[t]he overseas operations of [appellant] continue to grow and to become a more substantial part of the company’s strength and profitability.” Container Corporation of America, 1964 Annual Report 6, reproduced in Exhibit I to Stipulation of Facts. See generally id., at 6-9, 11.

The second noteworthy factor is the managerial role played by appellant in its subsidiaries’ affairs. We made clear in F.W. Woolworth Co. that a unitary business finding could not be based merely on “the type of occasional oversight—with respect to capital structure, major debt, and dividends—that any parent gives to an investment in a subsidiary . . . .” 458 U. S., at. As Exxon illustrates, however, mere decentralization of day-to-day management responsibility and accountability cannot defeat a unitary business finding. 447 U. S., at 224. The difference lies in whether the management role that the parent does play is grounded in its own operational expertise and its overall operational strategy. In this case, the business “guidelines” established by appellant for its subsidiaries, the “consensus” process by which appellant’s management was involved in the subsidiaries’ business decisions, and the sometimes uncompensated technical assistance provided by appellant, all point to precisely the sort of operational role we found lacking in F.W. Woolworth.

20 First, the one-third-each weight given to the three factors is essentially arbitrary. Second, payroll, property, and sales still do not exhaust the entire set of factors arguably relevant to the production of income. Finally, the relationship between each of the factors and income is by no means exact. The three-factor formula, as applied to horizontally linked enterprises, is based in part on the very rough economic assumption that rates of return on property and payroll—as such rates of return would be measured by an ideal accounting method that took all transfers of value into account—are roughly the same in different taxing jurisdictions. This assumption has a powerful basis in economic theory: if true rates of return were radically different in different jurisdictions, one might expect a significant shift in investment resources to take advantage of that difference. On the other hand, the assumption has admitted weaknesses: an enterprise’s willingness to invest simultaneously in two jurisdictions with very different true rates of return might be adequately explained by, for example, the difficulty of shifting resources, the decreasing marginal value of additional investment, and portfolio-balancing considerations.

21 The arm’s-length approach is also often applied to geographically distinct divisions of a single corporation.

22 The stipulation of facts indicates that the tax returns filed by appellant’s subsidiaries in their foreign domiciles took into account “only the applicable income and deductions incurred by the subsidiary or subsidiaries in that country and not . . . the income and deductions of [appellant] or the subsidiaries operating in other countries.” App. 72. This does not conclusively demonstrate the existence of double taxation because appellant has not produced its foreign tax returns, and it is entirely possible that deductions, exemptions, or adjustments in those returns eliminated whatever overlap in taxable income resulted from the application of the California apportionment method. Nevertheless, appellee does not seriously dispute the existence of actual double taxation as we have defined it, Brief for Appellee 114-121, but cf. Tr. of Oral Arg. 28-29, and we assume its existence for the purposes of our analysis. Cf. Japan Line, 441 U. S., at 452, n. 17.

23 But see infra, at 34-35 (discussing whether state scheme is preempted by federal law).

24 Note that we deliberately emphasized in Japan Lines the narrowness of the question presented: “whether instrumentalities of commerce that are owned, based, and registered abroad and that are used exclusively in international commerce, may be subjected to apportioned ad valorem property taxation by a State.” 441 U. S., at 444.

25 Indeed, in Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. v. Caterpillar Tractor Co. , No. 81-349, which was argued last Term and carried over to this Term, application of worldwide combined apportionment resulted in a refund to the taxpayer from the amount he had paid under a tax return that included neither foreign income nor foreign apportionment factors.

26 We have no need to address in this opinion the constitutionality of combined apportionment with respect to state taxation of domestic corporations with foreign parents or foreign corporations with either foreign parents or foreign subsidiaries. See also n. 32, infra.

27 Cf. United States Draft Model Income Tax Treaty of June 16, 1981, Art. 9, reprinted in P-H Tax Treaties % 1022 (hereinafter Model Treaty) (“Where . . . an enterprise of a Contracting State participates directly or indirectly in the management, control or capital of an enterprise of the other Contracting State . . . and . . . conditions are made or imposed between the two enterprises in their commercial or financial relations which differ from those which would be made between independent enterprises, then any profits which, but for these conditions would have accrued to one of the enterprises, but by reason of those conditions have not so accrued, may be included in the profits of that enterprise and taxed accordingly.”); J. Bischel, Income Tax Treaties 219 (1978) (hereinafter Bischel).

28 See generally G. Harley, International Division of the Income Tax Base of Multinational Enterprises 143-160 (1981) (hereinafter Harley); Madare, , International Pricing: Allocation Guidelines and Relief from Double Taxation, 10 Tex. Int’l L. J. 108, 111-120 (1975)Google Scholar.

29 See Surrey, , Reflections on the Allocation of Income and Expenses Among National Tax Jurisdictions, 10 L. & Policy Int. Bus. 409 (1979)Google Scholar; Bischel 459-461, 464-466; Bittker, B. & Eustice, J., Federal Income Taxation of Corporations and Shareholders ¶ 15.06 (4th ed. 1979)Google Scholar; Harley, 143-160.

30 Another problem arises out of the treatment of inter-corporate dividends. Under formula apportionment as practiced by California, intercorporate dividends attributable to the unitary business are, like many other inter-corporate transactions, considered essentially irrelevant and are not included in taxable income. See n. 5, supra. If the arm’s-length method were entirely consistent, it would tax inter-corporate dividends when they occur, just as all other investment income is taxed. (In which State that dividend could be taxed is not particularly important, since the issue here is international rather than interstate double taxation. See Mobil, 445 U. S., at 447-448.) It could also be argued that this would not, strictly speaking, result in double taxation, since the income taxed would be income “of” the parent rather than income “of” the subsidiary. The effect, however, would often be to penalize an enterprise simply because it has adopted a particular corporate structure. In practice, therefore, most jurisdictions allow for tax credits or outright exemptions for inter-corporate dividends among closely-tied corporations, and provision for such credits or exemptions is often included in tax treaties. See generally Model Treaty Art. 23; Bischel 2. No suggestion has been made here that appellant’s dividends from its subsidiaries would have to be exempt entirely from domestic state taxation. and the grant of a credit, which is the approach taken by federal law, see 26 U. S. C. §§901 et seq., does not in fact entirely eliminate effective double taxation: the same income is still taxed twice, although the credit insures that the total tax is no greater than that which would be paid under the higher of the two tax rates involved. Moreover, once the Federal Government has allowed a credit for foreign taxes on a particular inter-corporate dividend, we are not persuaded why, as a logical matter, a State would have to grant another credit of its own, since the federal credit would have already vindicated the goal of not subjecting the taxpayer to a higher tax burden that it would have to bear if its subsdiary’s income were not taxed abroad.

31 At the federal level, double taxation is sometimes mitigated by provisions in tax treaties providing for inter-governmental negotiations to resolve differences in the approaches of the respective taxing authorities. See generally Model Treaty Art. 25; 2 New York University Fortieth Annual Institute on Federal Taxation §31.03[2] (1982) (hereinafter N. Y. U. Institute). But cf. Owens, , United States Income Tax Treaties: Their Role in Relieving Double Taxation, 17 Rutgers L. Rev. 428, 443-444Google Scholar (role of such provisions procedural rather than substantive). California, however, is in no position to negotiate with foreign governments, and neither the tax treaties nor federal law provides a mechanism by which the Federal Government could negotiate double taxation arising out of state tax systems. In any event, such negotiations do not always occur, and when they do occur they do not always succeed.

32 We recognize that the fact that the legal incidence of a tax falls on a corporation whose formal corporate domicile is domestic might be less significant in the case of a domestic corporation that was owned by foreign interests. We need not decide here whether such a case would require us to alter our analysis.

33 The Solicitor General did submit a brief opposing worldwide formula apportionment by a State in Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., No. 81-349, a case that was argued last Term, and carried over to this Term. Although there is no need for us to speculate as to the reasons for the Solicitor General’s decision not to submit a similar brief in this case, cf. Brief for National Governor’s Association and the State of Hawaii as Amicus Curiae 6-7, there has been no indication that the position taken by the Government in Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. still represents its views, or that we should regard the brief in that case as applying to this case.

34 See generally Model Treaty Art. 7(2); Bischel 33-38, 459-461.

35 See Model Treaty Art. 1(3); Bischel 718; N. Y. U. Institute §31.04[3].

36 See Bischel 7.

37 See 124 Cong. Rec. 18400, 19076 (1978).

38 There is now pending one such bill of which we are aware. See H. R. 2918, 98th Cong., 1st Sess. (1983).

1 The Court also appears to attach some weight to its view that California is unable “simply [to] adher[e] to one bright-line rule” to eliminate double taxation. See ante, at 28. From California’s perspective, however, a bright-line rule that avoids Foreign Commerce Clause problems clearly exists. The State simply could base its apportionment calculations on appellant’s United States income as reported on its federal return. This sum is calculated by the arm’s-length method, and is thus consistent with international practice and federal policy. Double taxation is avoided to the extent possible by international negotiation conducted by the Federal Government. California need not concern itself with the details of the international allocation, but could apportion the American income using its three factor formula.

2 Although there are a few foreign countries where wage rates, property values, and sales prices are higher than they are in California, appellant’s principal subsidiaries did not operate in such countries.

3 Similarly, there could be double taxation if the entire international community adopted California’s method of formula apportionment. Different jurisdictions might apply different accounting principles to determine wages, property values, and sales. Indeed, any system that calls for the exercise of any judgment leaves the possibility for some double taxation.

4 This is well illustrated by the protests that the Federal Government already has received from our principal trading partners. Several of these are reprinted or discussed in the papers now before the Court. See, e. g. , App. to Brief for the Committee on Unitary Tax as Amicus Curiae 7 (Canada); id., at 9 (France); id., at 13-16 (United Kingdom); id., at 17-19 (European Economic Community); App. to Brief for the International Bankers Association In California as Amicus Curiae in Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., O. T. 1981, No. 81-349, pp. 4-5 (Japan); Memorandum for the United States as Amicus Curiae in Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., O. T. 1981, No. 81-349, p. 3 (“[A] number of foreign governments have complained—both officially and unofficially—that the apportioned combined method . . . creates an irritant in their commercial relations with the United States. Retaliatory taxation may ensue . . . .”); App. to id., at 2a-3a (United Kingdom); id., at 8a-9a (Canada).

5 California is, of course, free to tax its own corporations more heavily than it taxes out-of-state corporations.

6 The State could not raise the tax rate for appellant alone, or even for corporations engaged in foreign commerce, without facing constitutional challenges under the Equal Protection or the Commerce Clause.

7 Chicago Bridge & Iron, it might be noted, is a case in which the state tax is imposed on an American parent corporation.

8 The Court relies on the absence of a “clear federal directive.” See ante, at 32, 34-35. In light of the Government’s position, as stated in the Solicitor General’s memorandum, see supra, at 8, the absence of a more formal statement of its view is entitled to little weight.

- 3

- Cited by