Article contents

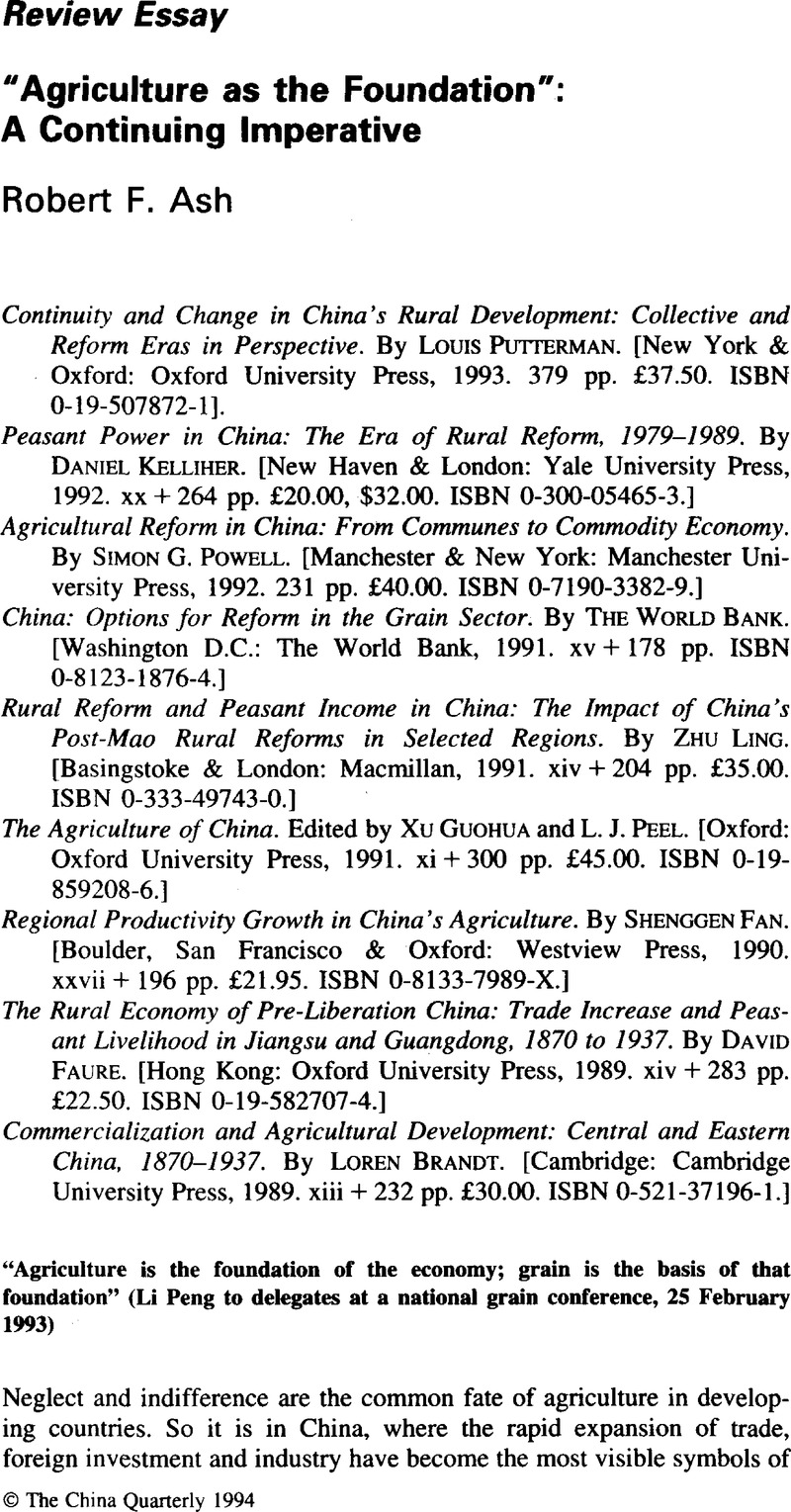

“Agriculture as the Foundation”: A Continuing Imperative

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essay

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The China Quarterly 1994

References

1. Agriculture's share in the gross value of agricultural and industrial output (GVAIO) rose from 24.8% to 27.1% between 1978 and 1985. By 1990 it had returned to the 1978 level (24.3%), falling to 17.2% in 1993. But note that agriculture's share of total employment has fallen substantially under the impact of post-1978 reforms (from 71 % (1978) to 57% (1993)) (figures from State Statistical Bureau (SSB), Zhongguo tongji zhaiyao, 1994 (A Statistical Survey of China, 1994), hereafter TJZY (SSB Publishing House, 1994, p. 14)).

2. Thus, Deng Liqun in 1981: “… whoever forgets about the peasants and does not serve them, the peasants will cast aside”; and in the same year, Du Runsheng: “… if the situation in the countryside is good, then the whole nation is at peace; otherwise there is turmoil and upheaval” (both quoted by Kelliher, pp. 52–53).

3. In a derogatory reference whose significance nobody reared on the orthodoxy of a severely exploited peasantry at the hands of the pre-1949 Nationalist (Kuomintang) government could have missed, peasants even began to refer to the Chinese Communist Party as the “guamindang” – the “fleece-the-people party.” See also Hishida, Masahara, “State-society relations” (paper presented at the Third Japan–U.S. Symposium on China, 15 July 1993).Google Scholar For a more popular view of peasant unrest in the early 1990s, see Far Eastern Economic Review, 15 July 1993.

4. Quoted in Hong Kong, Dagong bao, 17 June 1994.

5. See Jingji ribao, 28 June 1994; Renmin ribao, 25 July 1994; and reports in three Hong Kong sources (Ming bao, 3 July 1994; Zhengming, 6 August 1994; and Xin bao, 12 August 1994).

6. Agriculture's share of RSVO fell from 69% (1980) to 36% (1992), rural industry's contribution meanwhile rising from 19% to 50%. During the same period, crop farming's share of GVAO declined from 77% (itself considerably higher than the corresponding 1957 figure) to 55%. In 1992 grain accounted for 74% of the total sown area, compared with 80% in 1980. (All figures from SSB, Zhongguo tongji nianjian, 1993 (Statistical Yearbook of China, 1993), hereafter TJNJ (SSB Publishing House, 1993, pp. 333, 335 and 358).

7. The fact that agricultural workers constituted 78% of the total rural labour force in 1992 (cf. 90% in 1978) highlights the problem of agricultural surplus labour, as well as that of differences in productivity that characterize agricultural and non-agricultural activities in the countryside.

8. Shen, T. H., Agricultural Resources of China (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1951).Google ScholarPubMed

9. Oi, Jean, State and Peasant in Contemporary China: The Political Economy of Village Government (Berkeley & London: University of California Press, 1989)Google Scholar; and Shue, Vivienne, The Reach of the Chinese State: Sketches of the Chinese Bosy Plitic (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988).Google Scholar

10. See, for example, Runsheng, Du, “Woguo nongcun fazhan de jige wenti” (“Several questions relating to China's agricultural development”), Zhongguo nongye nianjian 1984 (Chinese Agricultural Yearbook 1984) (Beijing: Agricultural Publishing House, 1985; pp. 5–9).Google Scholar

11. Putterman also postulates the same imperative operating at a household level during the first half of the 1980s: “the grain market… was thin enough so that virtually all rural households at Dahe [township] continued to grow grain for their own subsistence needs…”. (P-121).

12. The average annual rate of growth total grain output fell from 4.4% (1978–84) to 0.01% (1984–89) (JJZY 1994, p. 63).

13. Ibid.

14. Between 1989 and 1992, these regions contributed almost two-thirds (22 out of 35 million tonnes) of incremental grain output (TJNJ, 1990, p. 367; TJNJ 1993, p. 368). Put differently, average growth during this period was 11.7% p.a. in the north-east and Inner Mongolia, compared with a mere 1.2% p.a. in the rest of the country.

15. One source has recently predicted that China's food needs will grow so rapidly that by the early decades of the next century, its import requirements may be such a drain on world grain supplies as to threaten the ability of other developing countries to feed themselves. See Brown, Lester R., “Question for 2030: who will be able to feed China?” International Herald Tribune (IHT), 28 September 1994Google Scholar and “When China's scarcities become the world's problem,” IHT, 29 September 1994.

16. Thus, “an import based food security strategy… would have to be managed very carefully to avoid placing… pressure on world market prices for these commodities” (p. 46).

17. Myers, Ramon H., The Chinese Peasant Economy: Agricultural Development in Hopei and Shantung, 1890–1949 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970).Google Scholar

18. Thus, Brandt: “external factors… explain about 75 percent of the annual variability [of local rice prices] in Changsha, a market more than 800 miles upriver from Shanghai. In Wuhu and markets nearer to Shanghai, the percentage was even higher” (p. 50).

19. Cf. Brandt: “the rising productivity, increased per capita consumption of cloth, and rise in the terms of trade in agriculture's favour can only mean that incomes in the rural sector were rising throughout much of the period” (p. 134); and Faure: “the rural economy in Jiangsu and Guangdong, especially in areas that produced export crops, saw considerable prosperity … [which]… must have translated into a higher standard of living for the majority of fanners and owner-cultivators, as well as tenants” (p. 202).

- 1

- Cited by