Book contents

- Fetal Therapy

- Fetal Therapy

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Section 1: General Principles

- Section 2: Fetal Disease: Pathogenesis and Treatment

- Red Cell Alloimmunization

- Structural Heart Disease in the Fetus

- Fetal Dysrhythmias

- Manipulation of Fetal Amniotic Fluid Volume

- Fetal Infections

- Fetal Growth and Well-being

- Preterm Birth of the Singleton and Multiple Pregnancy

- Complications of Monochorionic Multiple Pregnancy: Twin-to-Twin Transfusion Syndrome

- Complications of Monochorionic Multiple Pregnancy: Fetal Growth Restriction in Monochorionic Twins

- Complications of Monochorionic Multiple Pregnancy: Twin Reversed Arterial Perfusion Sequence

- Complications of Monochorionic Multiple Pregnancy: Multifetal Reduction in Multiple Pregnancy

- Fetal Urinary Tract Obstruction

- Pleural Effusion and Pulmonary Pathology

- Surgical Correction of Neural Tube Anomalies

- Fetal Tumors

- Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

- Fetal Stem Cell Transplantation

- Gene Therapy

- Section III: The Future

- Index

- References

Manipulation of Fetal Amniotic Fluid Volume

from Section 2: - Fetal Disease: Pathogenesis and Treatment

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 October 2019

- Fetal Therapy

- Fetal Therapy

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Section 1: General Principles

- Section 2: Fetal Disease: Pathogenesis and Treatment

- Red Cell Alloimmunization

- Structural Heart Disease in the Fetus

- Fetal Dysrhythmias

- Manipulation of Fetal Amniotic Fluid Volume

- Fetal Infections

- Fetal Growth and Well-being

- Preterm Birth of the Singleton and Multiple Pregnancy

- Complications of Monochorionic Multiple Pregnancy: Twin-to-Twin Transfusion Syndrome

- Complications of Monochorionic Multiple Pregnancy: Fetal Growth Restriction in Monochorionic Twins

- Complications of Monochorionic Multiple Pregnancy: Twin Reversed Arterial Perfusion Sequence

- Complications of Monochorionic Multiple Pregnancy: Multifetal Reduction in Multiple Pregnancy

- Fetal Urinary Tract Obstruction

- Pleural Effusion and Pulmonary Pathology

- Surgical Correction of Neural Tube Anomalies

- Fetal Tumors

- Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

- Fetal Stem Cell Transplantation

- Gene Therapy

- Section III: The Future

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

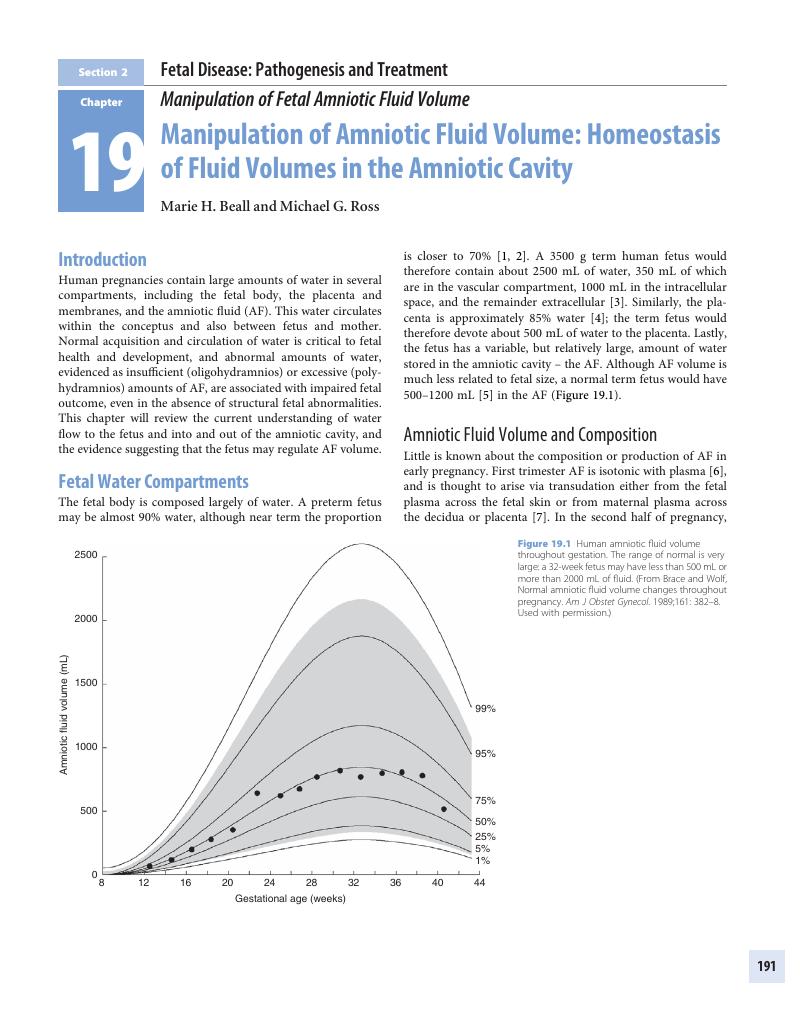

- Fetal TherapyScientific Basis and Critical Appraisal of Clinical Benefits, pp. 191 - 214Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020