Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Part I Basic science

- 1 Trophoblast invasion in pre-eclampsia and other pregnancy disorders

- 2 Development of the utero-placental circulation: purported mechanisms for cytotrophoblast invasion in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia

- 3 In vitro models for studying pre-eclampsia

- 4 Endothelial factors

- 5 The renin–angiotensin system in pre-eclampsia

- 6 Immunological factors and placentation: implications for pre-eclampsia

- 7 Immunological factors and placentation: implications for pre-eclampsia

- 8 The role of oxidative stress in pre-eclampsia

- 9 Placental hypoxia, hyperoxia and ischemia–reperfusion injury in pre-eclampsia

- 10 Tenney–Parker changes and apoptotic versus necrotic shedding of trophoblast in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia

- 11 Dyslipidemia and pre-eclampsia

- 12 Pre-eclampsia a two-stage disorder: what is the linkage? Are there directed fetal/placental signals?

- 13 High altitude and pre-eclampsia

- 14 The use of mouse models to explore fetal–maternal interactions underlying pre-eclampsia

- 15 Prediction of pre-eclampsia

- 16 Long-term implications of pre-eclampsia for maternal health

- Part II Clinical Practice

- Subject index

- References

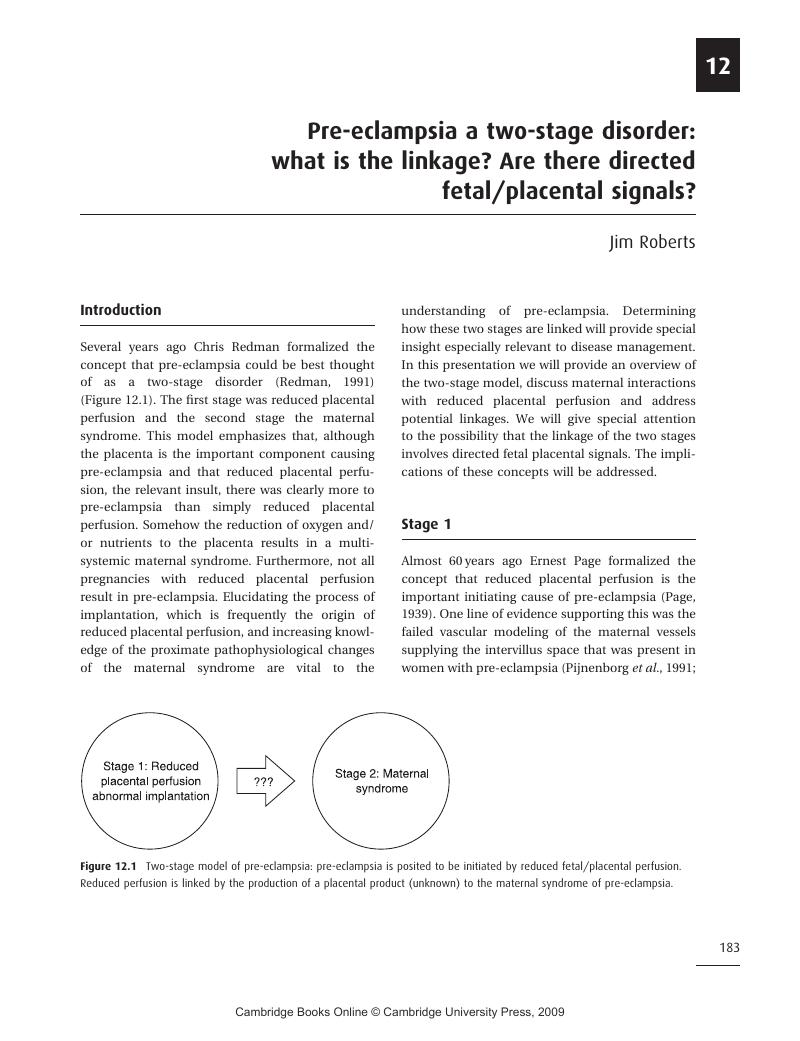

12 - Pre-eclampsia a two-stage disorder: what is the linkage? Are there directed fetal/placental signals?

from Part I - Basic science

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 September 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Part I Basic science

- 1 Trophoblast invasion in pre-eclampsia and other pregnancy disorders

- 2 Development of the utero-placental circulation: purported mechanisms for cytotrophoblast invasion in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia

- 3 In vitro models for studying pre-eclampsia

- 4 Endothelial factors

- 5 The renin–angiotensin system in pre-eclampsia

- 6 Immunological factors and placentation: implications for pre-eclampsia

- 7 Immunological factors and placentation: implications for pre-eclampsia

- 8 The role of oxidative stress in pre-eclampsia

- 9 Placental hypoxia, hyperoxia and ischemia–reperfusion injury in pre-eclampsia

- 10 Tenney–Parker changes and apoptotic versus necrotic shedding of trophoblast in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia

- 11 Dyslipidemia and pre-eclampsia

- 12 Pre-eclampsia a two-stage disorder: what is the linkage? Are there directed fetal/placental signals?

- 13 High altitude and pre-eclampsia

- 14 The use of mouse models to explore fetal–maternal interactions underlying pre-eclampsia

- 15 Prediction of pre-eclampsia

- 16 Long-term implications of pre-eclampsia for maternal health

- Part II Clinical Practice

- Subject index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Pre-eclampsiaEtiology and Clinical Practice, pp. 183 - 194Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2007

References

- 4

- Cited by