78 results

Utility of Repeat Endpoint Quaking-Induced Conversion Testing in Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease

-

- Journal:

- Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Volume 50 / Issue 6 / November 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 October 2022, pp. 929-931

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Virtual engagement of under-resourced communities: Lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic for creating crisis-resistant research infrastructure

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Clinical and Translational Science / Volume 6 / Issue 1 / 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 April 2022, e44

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Vision

- Published online:

- 17 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021, pp ix-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

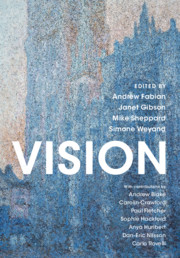

Vision

-

- Published online:

- 17 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021

Figures

-

- Book:

- Vision

- Published online:

- 17 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021, pp x-xix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Vision

- Published online:

- 17 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Vision

- Published online:

- 17 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021, pp vi-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes on Contributors

-

- Book:

- Vision

- Published online:

- 17 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021, pp xx-xxiii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Vision

- Published online:

- 17 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021, pp 197-204

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Vision

- Published online:

- 17 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021, pp xxiv-xxiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A distributed geospatial approach to describe community characteristics for multisite studies

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Clinical and Translational Science / Volume 5 / Issue 1 / 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 February 2021, e86

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Novel method of calculating adjusted antibiotic use by microbiological burden

-

- Journal:

- Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology / Volume 42 / Issue 6 / June 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 January 2021, pp. 688-693

- Print publication:

- June 2021

-

- Article

- Export citation

Stratifying major depressive disorder by polygenic risk for schizophrenia in relation to structural brain measures

-

- Journal:

- Psychological Medicine / Volume 50 / Issue 10 / July 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 July 2019, pp. 1653-1662

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Garboldisham Macehead: its Manufacture, Date, Archaeological Context and Significance

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 83 / December 2017

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2017, pp. 383-394

- Print publication:

- December 2017

-

- Article

- Export citation

Field Presence of Glyphosate-Resistant Horseweed (Conyza Canadensis), Common Lambsquarters (Chenopodium Album), and Giant Ragweed (Ambrosia Trifida) Biotypes with Elevated Tolerance to Glyphosate

-

- Journal:

- Weed Technology / Volume 22 / Issue 3 / September 2008

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 January 2017, pp. 544-548

-

- Article

- Export citation

Verbal Initiation, Suppression, and Strategy Use and the Relationship with Clinical Symptoms in Schizophrenia

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society / Volume 22 / Issue 7 / August 2016

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 June 2016, pp. 735-743

-

- Article

- Export citation

Beaker people in Britain: migration, mobility and diet

- Part of

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

5 - ‘A New Mode of the Existence of Truth’: Rancière and the Beginnings of Modernity 1780–1830

- from SECTION I - Coordinates

-

-

- Book:

- Rancière and Literature

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 15 September 2017

- Print publication:

- 11 May 2016, pp 99-122

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contributors

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy

- Published online:

- 05 August 2015

- Print publication:

- 27 April 2015, pp ix-xxx

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Concepts of Creativity in Seventeenth-Century England

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 05 March 2014

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2013, pp 343-354

-

- Chapter

- Export citation