168 results

Chapter 4 - Vegetarianism as Religion

-

- Book:

- Vegetarianism and Veganism in Literature from the Ancients to the Twenty-First Century

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 104-136

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Cambridge Companion to Women Composers

-

- Published online:

- 23 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2024

Knowledge and God

-

- Published online:

- 01 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2024

-

- Element

- Export citation

4 - Congregation-Based Community Organizing

- from Part I - Organizing and Activism

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of Community Empowerment

- Published online:

- 18 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp 110-138

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Languages of Belief

-

- Book:

- Some New World

- Published online:

- 29 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 April 2024, pp 24-67

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - The Theology of the Book of Habakkuk

-

- Book:

- The Theology of the Books of Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah

- Published online:

- 28 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 04 April 2024, pp 104-172

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Some New World

- Myths of Supernatural Belief in a Secular Age

-

- Published online:

- 29 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 April 2024

The Theology of the Books of Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah

-

- Published online:

- 28 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 04 April 2024

Thomas Aquinas on Non-Theological Faith

-

- Journal:

- New Blackfriars ,

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 February 2024, pp. 1-14

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Human Beings and Ethics in the Thought of Herbert McCabe

-

- Journal:

- New Blackfriars / Volume 105 / Issue 3 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 February 2024, pp. 294-308

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

An argument for the perspectival account of faith

-

- Journal:

- Religious Studies , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 February 2024, pp. 1-20

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Faith and the Absurd: Kierkegaard, Camus and Job’s Religious Protest

-

- Journal:

- Harvard Theological Review / Volume 117 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 February 2024, pp. 293-316

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Secret Debts

-

- Book:

- The Theology of Debt in Late Medieval English Literature

- Published online:

- 04 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 50-81

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Method of Metaphysics and the Architectonic: Remarks on Gava’s Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and the Method of Metaphysics

-

- Journal:

- Kantian Review / Volume 29 / Issue 1 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 January 2024, pp. 115-124

- Print publication:

- March 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

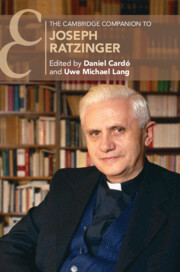

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Ratzinger

-

- Published online:

- 25 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023

Chapter 10 - The Despair of Judge William

-

-

- Book:

- Kierkegaard's <i>Either/Or</i>

- Published online:

- 16 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 171-187

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Faith as skill: an essay on faith in the Abrahamic tradition

-

- Journal:

- Religious Studies , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 November 2023, pp. 1-21

-

- Article

- Export citation

2 - Political Virtues?

-

- Book:

- Augustine on the Nature of Virtue and Sin

- Published online:

- 10 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 45-81

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - God’s Justice and the End of the Torah

-

- Book:

- Paul and the Resurrection of Israel

- Published online:

- 02 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 221-270

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - Religion in the Tokugawa Period

- from Part III - Social Practices and Cultures of Early Modern Japan

-

-

- Book:

- The New Cambridge History of Japan

- Published online:

- 15 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 443-477

-

- Chapter

- Export citation