Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Maps

- 1 Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam

- 2 Java

- 3 Japan

- 4 China: The Guqin Zither

- 5 Chinese Opera

- 6 North India

- 7 South India

- 8 Mande Jaliyaa

- 9 North American Jazz

- 10 Europe

- 11 North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean: Andalusian Music

- 12 The Eastern Arab World

- 13 Turkey

- 14 Iran

- 15 Uzbekistan and Tajikistan

- Notes

- Bibliographies

- Index

4 - China: The Guqin Zither

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Maps

- 1 Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam

- 2 Java

- 3 Japan

- 4 China: The Guqin Zither

- 5 Chinese Opera

- 6 North India

- 7 South India

- 8 Mande Jaliyaa

- 9 North American Jazz

- 10 Europe

- 11 North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean: Andalusian Music

- 12 The Eastern Arab World

- 13 Turkey

- 14 Iran

- 15 Uzbekistan and Tajikistan

- Notes

- Bibliographies

- Index

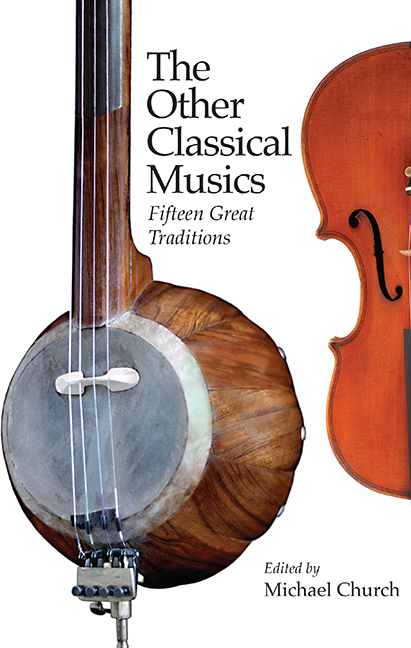

Summary

A scholar – and owner of a zither – pauses in his climb up a mountain; as a rich man he can afford a servant or pupil to carry his heavy instrument to the top. After a while he sits down cross-legged under a pine tree, places his instrument on his lap and begins to play for the gods – or for himself. The wind touches his strings furtively, and he might sing a poem or two, plucking the strings randomly to produce soft sounds: some evasive and questioning slide tones, and a sonorous buzz on the lowest string, reminiscent of the sound of a distant bell; or perhaps some clear and pure harmonics in the highest register, brought forth by touching the strings very lightly. All this is interspersed with contemplative pauses; the music merges delicately with the surrounding silence. The mist on the mountain serves as a reminder of the world's deep emptiness: vast crags and abysses mock the futility of human strife and ambition.

Is this a real performance? It might be, but more likely it's just a scene from our imagination, or from an old painting or ink-drawing portraying an age-old ideal of qin performance. Back in the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), playing the qin, China's seven-stringed classical zither, was one of the four ‘gentlemanly skills’, along with chess, calligraphy and painting; one of the pastimes of Chinese intellectuals. Sage-like figures playing the instrument are a popular topic in classical lore; Confucius himself (551–479 BCE) was reputed to be a fine player. Steeped in both Confucian and Daoist philosophy, the qin is strongly associated with the natural world, and with its assumed ability to ‘sound the cosmos’. A performer playing on top of a mountain or in a bamboo grove remains a potent fantasy of what qin players try to achieve: they foster a dream of spiritual communion with nature, even to the extent of themselves vanishing at the end of their music. For thousands of years qin players have aspired to attain wisdom and redemption with their art, and through it to live in blissful harmony with their environment. These ideals are still cherished by some in China today.

The Chinese visual arts abound in pictures of outdoor zither performers – mostly men, but sometimes also women – playing their instrument in garden pavilions, or amid impressive scenery.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Other Classical MusicsFifteen Great Traditions, pp. 104 - 125Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015

- 1

- Cited by