Book contents

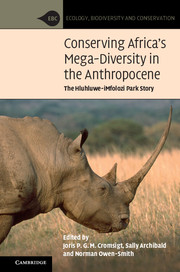

- Conserving Africa's Mega-Diversity in the AnthropoceneThe Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park Story

- Ecology, Biodiversity and Conservation

- Conserving Africa's Mega-Diversity in the Anthropocene

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Further Details on Zulu Place Names in the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park

- Acknowledgements

- Preamble

- Map

- Part I Setting the Scene

- 1 Anthropogenic Influences in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park: From Early Times to Recent Management

- 2 The Abiotic Template for the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park's Landscape Heterogeneity

- 3 Long-Term Vegetation Dynamics within the Hluhluwe iMfolozi Park

- 4 Temporal Changes in the Large Herbivore Fauna of Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park

- Part II Theoretical Advances in Savanna Ecology

- Part III Where Science and Conservation Management Meet

- Index

- Plate Section (PDF Only)

- References

2 - The Abiotic Template for the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park's Landscape Heterogeneity

from Part I - Setting the Scene

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 March 2017

- Conserving Africa's Mega-Diversity in the AnthropoceneThe Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park Story

- Ecology, Biodiversity and Conservation

- Conserving Africa's Mega-Diversity in the Anthropocene

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Further Details on Zulu Place Names in the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park

- Acknowledgements

- Preamble

- Map

- Part I Setting the Scene

- 1 Anthropogenic Influences in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park: From Early Times to Recent Management

- 2 The Abiotic Template for the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park's Landscape Heterogeneity

- 3 Long-Term Vegetation Dynamics within the Hluhluwe iMfolozi Park

- 4 Temporal Changes in the Large Herbivore Fauna of Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park

- Part II Theoretical Advances in Savanna Ecology

- Part III Where Science and Conservation Management Meet

- Index

- Plate Section (PDF Only)

- References

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Conserving Africa's Mega-Diversity in the AnthropoceneThe Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park Story, pp. 33 - 55Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017

References

2.7 References

- 11

- Cited by