In Chapters 1, 2, and 3, we developed a framework that faculty, staff, and administrators can employ to bring purposeful, effective support to students in the pursuit of the four goals that are central to their professional development and formation:

Ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need;

a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client;

a client-centered, problem-solving approach and good judgment that ground the student’s responsibility and service to the client; and

well-being practices.

Chapter 4 built on that framework, offering ten core principles to guide and inform faculty, staff, and administrators as they undertake the work of supporting students toward the four PD&F goals. The focus was on principles that will make everything easier, more efficient, and more effective in practice.

In this chapter, we keep with the emphasis on the practical and turn attention to the very practical matter of how to proceed in a law school. Each law school is an institution with diverse stakeholders who possess differing interests. It is an institution with multiple priorities and limited resources. Like many other institutions, it can exhibit signs of resistance to change and skepticism of innovation. With those realities in mind, this chapter provides nine practical implementation suggestions. All nine are premised on the expectation that progress likely will be incremental, that interest in more purposeful support of PD&F goals will need to be cultivated, and that many in the law school community have much still to learn about professional development and formation. Behind all nine suggestions, too, is the belief that all the major stakeholders of a law school do in fact have something to gain from more purposeful support of PD&F goals. In seeking their engagement and participation, it is crucial to “go where they are” – to appreciate the perspectives, interests, and needs of each major stakeholder (faculty, staff, administrators, students, legal employers, and the legal profession itself), and to build bridges that connect stakeholders to the project of fostering each student’s growth toward later stages of the four PD& F goals.

5.1 Assess Local Conditions with Respect to the Faculty, Staff, and Administrators

The first practical implementation suggestion is to assess local conditions among faculty, staff, and administrators at the law school. Are any of them interested in taking even small steps to help each student develop to the next level on any of the four goals? Remember that there are many on-ramps to these four foundational PD&F goals, but the various stakeholders in the law school may need help to see how their individual interests are served by fostering each student’s growth toward later stages of the four foundational goals. Law schools, in the authors’ experience, are relatively “siloed.” Each stakeholder tends to concentrate on a discrete area of responsibility and can be unaware of or indifferent to matters arising in another area. What are the enlightened self-interest reasons for each siloed group, framed in the language of that group, to foster student growth toward these goals?

Earlier discussion in Chapter 2 discussed the perspectives of the major internal stakeholders and how their self-interests might be served by stronger law school support of PD&F goals Here, we expand on the idea, illustrating how particular various stakeholders might identify and associate with one or another of the four PD&F goals.

The first goal – fostering each student’s growth to later stages of ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need – may find the greatest initial interest and support because many faculty and staff of all types are concerned about the weak levels of initiative and commitment that they discern in some of their students. Indeed, one-third of all schools have adopted an institutional learning outcome to foster each student’s self-directed or self-regulated learning. Chapter 1 emphasized that student growth toward later stages of self-directed learning improves the probability of stronger academic performance, bar passage, and postgraduation employment outcomes. Chapter 4 in addition emphasized that a continuous coaching model is the most effective curriculum to foster this type of student growth while also serving diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and Belonging goals by increasing historically underserved students’ sense of belonging and general student well-being. Improved outcomes on these fronts should prove attractive to many faculty, staff, and administrators, paving the way to interest in promoting PD&F goals. Podium faculty, on the other hand, should see that later stage growth on this learning outcome promotes achievement of the cognitive goals that podium faculty set for students. Even if podium faculty are not ready to incorporate the first PD&F goal in their own teaching, they might at least endorse its importance and give “cross-selling” support to its pursuit elsewhere in the law school, signaling to students that the goal needs to be taken seriously.

With respect to the second goal – fostering each student’s growth toward later stages of a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client – many faculty, staff, and administrators may agree that a fiduciary mindset or disposition is important. They may, however, find the goal too abstract or be skeptical that legal education can foster this type of growth. It may help if they see a more concrete learning outcome that builds on a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client. Chapter 4 emphasized that significant numbers of law schools have adopted learning outcomes that rest upon this foundation. Table 24 indicates the percentage of law schools that have adopted institutional learning outcomes that are sub-competencies related to this second goal.

Table 24 Percentage of law schools adopting a learning outcome building on a student’s internalized responsibility and service to others

Where the faculty has adopted any of these learning outcomes (e.g., pro bono service, cultural competency, teamwork/collaboration), the faculty and staff most interested in that outcome will be a promising group to support further steps. Given societal challenges regarding racial justice, for instance, there may be faculty, staff, and administrators drawn particularly toward fostering each student’s growth toward later stages of pro bono service to the disadvantaged and access to justice or to cultural competency. Perhaps faculty and staff interested in DEI and Belonging or student well-being might see that learning outcomes relating to building relationships and intrinsic meaning will promote student belonging and well-being.

The third PD&F goal – fostering a client-centered problem-solving approach and good judgment that ground each student’s responsibility and service to the client – links the general fiduciary mindset and disposition language of the second goal to the specific competencies that clients and legal employers want. Some faculty and staff – particularly those who are concerned with student readiness for practice and success in the employment market – may find this an appealing bridge. It connects legal doctrine and legal analysis to their concerns in the form of client-centered problem solving and good judgment.

The fourth PD&F goal – helping each student to internalize well-being practices – will be of great interest to faculty and staff focused on student stress and anxiety, depression, and substance abuse. As we discussed in Chapter 1, there are important links between Goal 1 (internalizing a commitment to continuous professional development), Goal 2 (internalizing a deep responsibility and service orientation to others), and the basic psychological needs that contribute to well-being.

5.2 Build a “Coalition of the Willing”

A second practical implementation suggestion is to build a “coalition of the willing” who want to help move the school forward in fostering student growth on any of the four PD&F goals (or any of their sub-competencies). In the initial period of experimentation, focus on gradual small steps that the coalition can try, and keep the faculty informed. The authors’ experience indicates that success can be had with small “pilot projects” that take advantage of the substantial autonomy that professors have in their courses and hence may not require formal approval. Suppose, for instance, that the coalition of the willing includes all the professors who teach a particular required course. These faculty members are well positioned to experiment with a formation-oriented pedagogy that all students might thus experience. Professors teaching courses in a distance-learning format might find a pilot project attractive, as teamwork and team projects lend themselves well to the online learning environment and provide means for students to form relationships; build community; and develop teamwork, collaboration, and communication competencies. Interested faculty and staff might try a pilot project focused on a continuous coaching model (outlined in Chapter 4) for (1) historically underserved students to increase their sense of belonging and in turn their academic and postgraduation success, (2) students most at risk of bar examination failure to foster their growth to later stages of self-directed learning and thus higher probabilities of bar passage, or (3) students identified by academic support as needing help regarding their well-being.

It is important to focus on small, gradual steps and choose pilot projects that are both practicable and have a good probability of success given local conditions. If possible, postpone initiatives that require a faculty vote until after there have been several successful pilot projects so proponents from the coalition of the willing can share their positive experiences with their colleagues. Those colleagues may come to embrace purposeful law school support of PD&F goals, but they must first become acquainted with the innovation and hear of its practicality and its benefits.Footnote 1

5.3 Build a Learning Community of Faculty and Staff Interested in Any of the Four PD&F Goals

This practical implementation suggestion builds on the idea of a coalition of the willing with a next step: the creation of a learning community. A faculty and staff learning community regularly discusses how most effectively to foster each student’s growth toward later stages of the four PD&F goals.Footnote 2 The learning community can provide feedback to individual faculty and staff members regarding curriculum ideas, break down the silos among faculty and staff, and become a source for information that can help other faculty and staff grow in their appreciation of the positive benefits and feasibility of supporting PD&F goals.

Medical education’s experience is that one-time faculty development interventions are not as robust in impact as longitudinal interventions. It is beneficial whenever possible to have ongoing faculty and staff development where participants share successes, discuss challenges, learn new skills, and recalibrate.Footnote 3 Learning communities at individual schools can reach out to learning communities at other schools that are working on the same learning outcomes.

Learning communities also can be the laboring oars on curricular change over time – including the taking of the gradual steps that can evolve into a coordinated progression of modules in the curriculum on a specific PD&F goal. The traditional law school committee that addresses curriculum development tends to perform a reactive function, reacting to faculty proposals regarding courses at a course level. As Steven Bahls points out, “[i]f curricular decisions are made primarily at the course level, students do not have sufficient assurance that they will have opportunities to achieve the overall outcomes necessary to prepare them to be responsible members of the profession.”Footnote 4 To move the curriculum over time toward a coordinated, sequenced progression of modules on a PD&F goal, the law school should have a proactive committee of faculty and staff members with on-the-ground understanding of that PD&F goal as it applies in the school.

5.4 Always “Go Where They Are” with Respect to Faculty, Staff, and Administrators

A fourth practical implementation suggestion borrows from Principle 3 in Chapter 4 – the principle that you should go where they are with students; take into account that students are at different developmental stages of growth on PD&F goals; and, accordingly, engage each student at the student’s present developmental stage. It is wise to extend the same concept to faculty, staff, and administrators. A faculty member who has never experienced strong professional development and formation teaching or excellent guided reflection with a coach might think, for example, that any curriculum involving the four PD&F goals will require stand-up lectures on philosophy and ethics. Other faculty might hear “professional development” and think the topic is about “jobs,” “resume-crafting,” and “vocationalism” or about civility, dress codes, and injunctions against Rambo litigation tactics, and thus not worth serious academic or curricular attention.

It is important to listen and understand how faculty, staff, and administrator colleagues are “hearing” any discussion of these four foundational PD&F goals and related curricular steps. It may take repeated effort over time to clarify and develop understanding about the concepts in Chapters 1 through 4. If possible, “visit” one-on-one with faculty and staff to draw out and clarify what they are hearing and understanding. Doing so may reveal that some faculty and staff are drawn toward one PD&F goal, while others are drawn toward a different one. It also may suggest opportunities to better inform faculty and staff of the nature of professional identity formation and the ways that they and the law school can support student development.Footnote 5

With respect to faculty and staff who have little or no interest in these four PD&F goals, keep them informed. An “ask” of their time and energy in direct support of professional identity formation efforts might be unadvisable. But some may be willing, sooner or eventually later, to spend a few minutes with their students “cross-selling” the importance of the PD&F curriculum for the students’ future. Provide them a script of talking points to make matters easier and the cross-selling more effective.

5.5 Repeatedly Emphasize the Value and Importance of “Curating”

A fifth practical implementation suggestion is to repeatedly emphasize the concept of “curating” that was discussed in Chapter 2. There, we called for faculty and staff, in an enterprise-wide effort, to “curate” the experiences and environments that promote each student’s growth toward later stages of the four PD&F goals. This means connecting the experiences and environments to one another in an intelligently sequenced fashion, and guiding the students through them with a framework that helps each student understand the student’s own development through the process. Curating produces a more cogent program for students while using the law school’s resources more efficiently and effectively. Faculty can play a lead role in the design of the experiences and environments while coordinating with staff who have responsibility for some of the modules in an enterprise-wide curriculum. For example, a law school that has adopted a teamwork/collaboration learning outcome will want both faculty and staff who are advisors of student organizations like the law journal, the various competitions involving teams, and student government to work together to foster each student’s growth toward later stages on teamwork skills. Similarly, if a law school is emphasizing support to each student who is at some risk of failing the bar to grow to later stages of self-directed learning, the faculty, the academic support staff, and the dean of students will work together to do this.

As we noted in Chapter 2, a law school can improve its support of the four PD&F goals with an enterprise-wide curating strategy even if it declines to adopt competency-based education as its educational model. Chapters 3 and 4, which borrow from medical education’s twenty years of additional experience with competency-based education, present concepts that will be useful in an enterprise-wide curating strategy even if the law school is not embracing competency-based education. A school that declines to formally establish a Milestone Model as discussed in Chapter 4 might nonetheless discuss and reflect on what milestones might be associated with a specific learning outcome. Discussion and agreement on the stages of development would be extremely useful in conceptualizing how to curate useful experiences and environments for students that support their progress.

5.6 Recognize the Scope of the Challenge in Fostering a Shared Understanding among Faculty, Staff, and Administrators about the Stages of Student Development on Competencies beyond Those Most Familiar to Law Schools. Focus on Gradual Small Steps Tailored to Local Conditions

If legal education’s experience over the next twenty years is similar to medical education’s earlier two decades of experience with learning outcomes like the four foundational PD&F goals this book emphasizes, then a sixth practical implementation suggestion stands out. Be aware of the scope of the challenge, and focus on gradual small steps each year tailored to local conditions.

The biggest challenge for medical education has been that medical faculty and staff historically have not had a clear shared understanding (a shared mental model or mental representation) about

1. How the capacities, skills, and values beyond the traditional technical medical skills are defined;

2. how students develop through stages toward a defined level of competence at these other capacities, skills, and values; and

3. what curricular engagements are most effective to foster each student’s growth toward later stages of these other capacities, skills, and values.Footnote 6

Milestone Models, discussed in Chapter 3, proved to be a beneficial way for medical education to tackle the challenge and create clear shared understanding among faculty and staff.Footnote 7 When faculty, staff, and administrators – the coalition of the willing – select a specific competency included in the four PD&F goals and come to some agreement on students’ stages of development, they not only achieve a clear, shared understanding of the competency but also lay the groundwork for curating the environment and experiences of the students to foster student growth. Proceeding from common ground, they also will be moving toward some inter-rater reliability in assessment of the competency.

5.7 Emphasize That There Are Many Successful Examples That Can Be Followed or Adapted to Foster Student Growth toward Later Stages of the Four PD&F Goals – And Draw from Them

A seventh practical implementation suggestion is to emphasize to faculty and staff that there are many other law schools and groups working to foster student growth toward the four foundational PD&F goals and many successful examples of curriculum that could be built upon to fit local conditions. As the examples and sources discussed next illustrate, interested faculty and staff hardly need to start from scratch. Models and guides are available to make initiative practicable, easy to execute, efficient, compatible with one’s practices and values, and likely to succeed – the criteria that make it easier for people to change and innovate.Footnote 8 What follow here are just a few examples that show the wide range of models, ideas, and initiatives from which a law school might draw.

5.7.1 A Milestone Model on the Goal/Learning Outcome That Is of Most Interest Given Local Conditions

Faculty and staff may have a shared – although perhaps unwritten and unspoken – mental model of the stages of student development regarding the standard law school competencies of knowledge of doctrinal law, legal analysis, and legal research and writing. But they likely do not share an understanding of progressive stages of growth on the four PD&F goals and their sub-competencies, such as teamwork, pro bono service, or cross-cultural competency. For the reasons outlined in Chapters 3 and 4, it is important to strive for a shared mental model of the students’ stages of development on these learning outcomes. Articulating a Milestone Model on even a single competency – for instance, on ownership over a student’s own professional development (self-directed learning) – can help move faculty and staff toward shared understanding. It also can serve as a direct measure of assessment for accreditation purposes (Principle 10 in Chapter 4), with faculty and staff observing and assessing each student’s stage of development using the Milestone Model (Principle 8 in Chapter 4 on multi-source observation and assessment).

Models are available. Responding to the most common learning outcomes that law schools have been adopting, the Holloran Center organized national working groups of faculty and staff to create stage-development Milestone Models on self-directed learning, teamwork, cross-cultural competency, integrity, and honoring commitments as part of professionalism.Footnote 9 Other stage-development models have been reported in the scholarly literature.Footnote 10 Milestone Models for PD&F Goals 1, 2, 3, and 4 also may be found in Appendix B to Chapter 4.

5.7.2 A Required PD&F Curriculum in the 1L Year

A fast-growing number of law schools (more than sixty – almost a third of all law schools) are now requiring professional development and formation curriculum in the 1L year to respond to concerns about bar passage, postgraduation employment outcomes, and student well-being.Footnote 11 The learning outcomes for these new required 1L professional development and formation initiatives tend to pursue two principal themes: (1) developing and demonstrating self-understanding, self-direction, and discernment of the student’s path in the legal market and (2) developing and demonstrating the relationship and communication skills needed in the legal market.Footnote 12 These track closely with the first two foundational PD&F learning outcomes (ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need and a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client).

A recent example is the University of Richmond School of Law’s one-credit required course in the 1L year. The course’s learning outcomes emphasize (1) discerning the student’s own values as a member of the legal profession; (2) developing critical interpersonal lawyering skills; and (3) engaging in self-directed learning, including designing and implementing a written plan for ongoing professional development and well-being.Footnote 13 An example of a longer-standing required initiative is the University of St. Thomas School of Law’s Mentor Externship, which emphasizes (1) fostering the highest levels of professionalism; (2) developing the relationship skills necessary for professional success in any employment context; and (3) deepening and broadening each student’s professional competencies, emphasizing self-directed learning.Footnote 14

Required PD&F offerings that award credit hours have emphasized reflection exercises, simulations, group discussions, and some panel presentations.Footnote 15 Required courses that afford no credit hours most commonly have featured panel presentations and lectures. Several use self-assessments of some sort, and many also employ a mock interview.Footnote 16

These efforts to foster student guided reflection and self-awareness of strengths are in keeping with Principle 4 in Chapter 4 (stressing the importance of guided reflection to foster growth on the PD&F learning outcomes). They also model Principle 7 (urging law schools to help each student understand how new knowledge, skills, and capacities are building upon the student’s existing experience and strengths to achieve the student’s goals).

5.7.3 A Requirement That Each Student Create and Implement a Written Professional Development Plan with Coaching Feedback (the ROADMAP Curriculum)

The ROADMAP curriculumFootnote 17 is designed to help each student create a written professional development plan with coaching feedback starting in January or February of the 1L year and then implement the plan throughout the remaining time in law school. The objective is to better realize the student’s goals of bar passage and meaningful postgraduation employment. The ROADMAP steps are specifically designed to assist a student’s growth to later stages of development on (1) ownership over the student’s own professional development (self-directed learning); (2) a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client; and (3) a client-centered problem-solving approach and good judgment.Footnote 18 Student growth to later stages of the first two ROADMAP goals should contribute to student well-being as discussed in Chapter 1.

Coaching is an important element of the ROADMAP curriculum. Each student has a one-on-one meeting for forty-five to sixty minutes with a coach who provides feedback and encourages guided reflection. One of the coauthors, Professor Hamilton, has been organizing coaches for individual meetings with roughly 160 1L students each year since 2013. His experience indicates that many doctrinal faculty may be not well suited to the coaching role, as they lack significant, recent experience in law practice and also are unaccustomed to providing the kind of attentive listening that good coaching requires. The best coaches have tended to be alumni in practice, about five to ten years out of law school, who are excellent listeners and who have experienced good coaching themselves. The Holloran Center has a coaching guide included in the Appendix to this chapter and is working on an online training program for coaches that should be available in summer 2022.

The University of St. Thomas School of Law has recently extended the ROADMAP coaching model and begun assigning the best internal coaches among faculty and staff to the students most at risk of not passing the bar exam (based on 1L fall semester grades). This is a continuous coaching model over each student’s remaining two and a half years of law school. There is not yet data on whether this program is increasing bar passage probabilities for this group.

ABA Publications, the publisher of the ROADMAP, is publishing Critical Lawyering Skills: A Companion Guide to the ROADMAP, by Thiadora Pina, Laura Jacobus, and Rupa Bandari. This book approaches the ROADMAP learning outcomes through a lawyering skills framework with excellent reflective exercises each week for the student. The Companion Guide also has a Professor’s Manual.

The ROADMAP curriculum, with a coach or a faculty member using the coaching guide in Appendix E to this chapter or the Companion Guide, applies the following principles from Chapter 4 – Principle 3 (go where the students are), Principle 4 (on repeated opportunities for guided reflection and self-assessment), Principle 5 (on the importance of coaching), Principle 6 (on coaching at the key transition points of law school), Principle 7 (on helping the student see how new knowledge, skills, and capacities are helping the student achieve their goals and building on existing strengths and experiences), and Principle 10 (on the importance of direct measures that an observer, such as a coach, can employ to assess the student’s stage of development on a Milestone Model). The continuous coaching model for at-risk students regarding bar passage also can lead to the creation of portfolios for each student, meeting Principle 9.

5.7.4 A 1L Constitutional Law Curriculum That Also Fosters Student Professional Development and Formation

One of the coauthors, Professor Bilionis, has incorporated a PD&F objective into a basic required first-year course in constitutional law. In addition to traditional competencies, the course explicitly spotlights collaboration and teamwork. The course’s stated learning objectives include the student’s ability to “participate as a member of a professional community whose members work individually and together to continuously improve their capacities to serve clients and society.” (This is a community of practice as discussed in Principle 6 in Chapter 4.) From the outset and throughout the course, the significance of a broad range of competencies to successful law practice is emphasized. The value of collaboration and teamwork to the student’s own learning while in law school also is stressed.

Each student is randomly assigned to a team for the entire semester. In every class session, one or more teams is “on call” to be exceptionally well prepared to explore the assigned reading as well as a distributed problem that places students in contexts they will encounter in practice. The teams regularly confer prior to class, using whatever means they choose (face-to-face, Zoom, or asynchronously in writing). Also associated with every class is a short writing assignment that all students, within their teams, must undertake. Each student drafts a short response to a prompt provided by the professor and posts that response to the team’s own online discussion board. The team then reviews its postings and produces a response on behalf of the entire team, capturing the best insights from its members’ postings. These team responses are shared with the entire class.

Twice during the semester, the students are assigned a more substantial writing project – two memoranda that serve as capstones to two major portions of the course. The students share their own drafts with teammates, and each student is responsible for providing written feedback to a teammate during the drafting process. A third writing assignment – drafting of an answer to a practice examination – capstones another segment of the course. Students share their draft answers with the team, which then confers to reflect on the strengths of various answers, opportunities for improvement, and strategies for exam preparation and exam taking. In class, each team delivers an oral report on its discussions and reflections.

The foregoing writing assignments are assessed, with feedback provided to the team and also individually to each student. The team-based activities are graded as well, producing a grade for the team (with each team member receiving the same grade) that figures, along with the final examination, into a student’s final grade in the course.Footnote 19

Students report that the team experiences assist them in better learning the doctrinal material and advancing their analytical abilities. They also report that the team experiences contribute positively to their confidence and their appreciation of diversity. They relate that the experiences reinforce for them that all their classmates have strengths; that no one has all the answers and insights; that all have valuable perspectives to offer; and that their own individual development is strengthened by collaboration, feedback, and reflection. In the professor’s opinion, students have shown improved performance on the final examination.

The structure of the course reflects several of the principles from Chapter 4. Students see a Teamwork and Team Leadership Milestone Model and do a self-assessment using the model reflecting Principle 1. There are repeated opportunities for reflection emphasized by Principle 4. The team assignments and the teamwork needed to do them simulate practice and are authentic professional experiences as contemplated by Principle 6. By resorting to extensive peer feedback in addition to feedback and assessment from the professor, the course also draws on Principle 8’s acknowledgment of the potential of multi-observer feedback and assessment.

5.7.5 A 1L Required Course on the Legal Profession

A course at the Mercer University School of Law – “The Legal Profession” – presents another example of the possibilities with a 1L required course. The nature of the course is well captured in the textbook used in the course, authored by Patrick Emery Longan, Daisy Hurst Floyd, and Timothy W. Floyd and titled The Formation of Professional Identity: The Path from Student to Lawyer.Footnote 20 The authors urge the student reader to be intentionally proactive about the formation of the student’s professional identity (defined as an individual with a “deep sense of self in a particular role” who can answer the question “I am the kind of law student/lawyer who _____”) and to internalize the traditional core values of the profession into the student’s existing value system.Footnote 21

The authors define the traditional core values of the legal profession in terms of virtues – capacities or dispositions that bring a person closer to an ideal.Footnote 22 They argue that there is substantial consensus in the profession about “the virtues necessary to be the kind of lawyer who serves clients well and helps fulfill the public purposes of the profession”Footnote 23 and set out six professional virtues that the student should internalize into their existing value system to form a professional identity:Footnote 24

1. The virtue of competence;

2. the virtue of fidelity to the client;

3. the virtue of fidelity to the law;

4. the virtue of public spiritedness;

5. the virtue of civility; and

6. the virtue of practical wisdom (the master virtue).

The authors analyze each of the six virtues in similarly structured separate chapters that

1. Define the meaning of the virtue in the context of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct and the needs of clients, legal employers, and the profession;

2. explain what gets in the way of the lawyer’s developing and demonstrating the virtue;

3. offer strategies for cultivating the virtue;

4. provide discussion questions and problems; and

5. supply suggested readings.

The structure of the book reflects several of the best empirically researched principles for an effective curriculum fostering the formation of each student’s professional identity set forth earlier in Chapter 4. Consistent with Principle 4, it provides repeated opportunities for reflection on the responsibilities of the profession and development of the habit of reflective self-assessment on these responsibilities.Footnote 25 In the same vein, the book uses problems and discussion questions at the end of each chapter that create cognitive dissonance to challenge the student’s existing ideas and assumptions at the student’s current stage of development.Footnote 26 Modeling Principle 7, the authors provide instruction that helps each student understand how the curriculum is helping the student achieve their goals.Footnote 27

5.7.6 A PD&F Curriculum Development Resource to Be Published in 2022

Kelly Terry, Kendall Kerew, and Jerry Organ are authoring a book forthcoming in 2022, titled Becoming Lawyers: An Integrated Approach to Professional Identity Formation. The book is a resource for faculty and staff who are developing curriculum and assessment modules to foster student growth toward professional development and formation learning outcomes. Chapters of the book will cover (1) definitions of professional identity; (2) communicating the importance of professional identity formation; (3) assessing learning outcomes relating to professional identity; (4) incorporating professional identity into admissions and orientation; (5) incorporating professional identity into the 1L year; (6) incorporating professional identity into the 2L year; (7) incorporating professional identity into the 3L year; and (8) professional identity at graduation, the bar examination, and beyond.

5.8 Go Where the Students Are to Build a Bridge from Their Personal Goals to the Competencies That Clients, Legal Employers, and the Profession Need

Our eighth practical implementation suggestion, as well as the ninth that follows, concerns the importance of communicating the relevance and significance of PD&F curriculum features to stakeholders who have a natural interest in their success. The objective is to connect the stakeholders to the school’s PD&F efforts by bridging the self-interest of the stakeholders to the values and objectives served by PD&F goals. With connection comes greater motivation to engage and participate.

We appropriately begin here with students. Students have personal goals that bear a close relation to the competencies that clients, legal employers, and the profession report that they need and want in lawyers. To maximize student “buy in” and engagement with the PD&F curriculum, a law school will do well to meet students where they are and communicate the connection between the students’ own goals and PD&F competencies early, often, consistently, and in terms that students appreciate. The aim is for students to see that their own goals and PD&F competencies are conceptually related, and that the curriculum bridges them together and meaningfully promotes their advancement.

5.8.1 What Are the Students’ Goals?

We have reasonably good data on the goals of both applicants to law school and enrolled law students. The 2018 Association of American Law Schools (AALS) report, Before the JD: Undergraduate Views on Law School, is the first large-scale national study to examine what factors contribute to an undergraduate student’s decision to go to law school.Footnote 28 The AALS study is based on responses from 22,189 undergraduate students from 25 four-year institutions and 2,727 law students from 44 law schools.Footnote 29 The survey asked the undergraduates “how important are each of these characteristics to you when thinking about selecting a career?” The top seven characteristics that undergraduate students considering law school (and including, therefore, those selecting a law career) thought were “extremely important” are

1. Potential for career advancement – 62 percent;

2. opportunities to be helpful to others or useful to society/giving back – 54 percent;

3. ability to have a work-life balance – 50 percent;

4. advocate for social change – 37 percent;

5. potential to earn a lot of money – 31 percent;

6. opportunities to be original and creative/innovative – 27 percent; and

7. whether the job has high prestige/status – 22 percent.Footnote 30

A synthesis of the AALS data indicates the most important goal of undergraduate students considering law school is meaningful postgraduation employment with the potential for career advancement that “fits” the passion, motivating interests, and strengths of the student and offers a service career that is helpful to others and has some work/life balance. Achieving a high income is an additional key factor defining the meaningfulness of employment for about 30 percent of the students considering law school.Footnote 31

5.8.2 What Are the Competencies That Clients, Legal Employers, and the Profession Need?

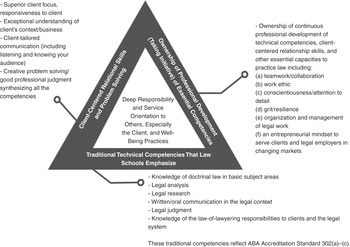

We also have reasonably good data on the competencies that clients and legal employers want. Chapter 1 and the Appendix to Chapter 1 outlined the data available and provided a Foundational Competencies Model discussed in Chapter 1 that we present again here for convenience in Figure 6.

Figure 6 Foundational Competencies Model based on empirical studies of the competencies clients and legal employers need

Legal education’s signature pedagogy – the case-dialogue method that dominates the first year of law school – emphasizes the cognitive skills of knowledge of doctrinal law and legal analysis, while legal writing and research, and to some degree legal judgment, also figure prominently in the standard law school curriculum.Footnote 32 These are the traditional technical competencies that law schools emphasize, as shown in Figure 6. Historically, the large majority of law schools have not had required curriculum to ensure each student’s attainment of a level of competence at the other capacities and skills on the upper two sides of Figure 6. As we have noted, however, the picture in law schools is changing. A significant number of law schools have recently adopted institutional learning outcomes that include capacities and skills beyond the traditional technical competencies. Medical education once subscribed to the view that new physicians would be fine so long as they were “really smart,” but it came to realize that this view was insufficient to meet patient and health care system needs.Footnote 33 The data on the learning outcomes that law schools are adopting indicate that legal education is coming to a similar realization of its own. Technical knowledge and cognitive skills are necessary but not sufficient to the effective practice of law. A much broader framework of capacities and skills for client-centered service is essential to meet client, legal employer, and legal system needs.

5.8.3 Building a Bridge of Coordinated Curricular Modules to Connect the Students’ Goals to Client, Legal Employer, and the Profession’s Needs

The law school’s PD&F curriculum can be envisioned as a bridge that unites the students’ goals of bar passage and meaningful postgraduation employment and the needs of clients, legal employers, and the legal system. Students who embrace that vision can “buy into” and engage in the curriculum more effectively. The law school can take two basic steps that will help students embrace that vision. Both steps draw upon the school’s capacity to communicate well and with appreciation of the student’s perspective.

The first step is to help the student envision and comprehend the bridge. Faculty, staff, and the administration can assist the student to understand

1. The full array of competencies that clients and legal employers want (this includes not only the traditional technical competencies in Figure 6 that all law schools emphasize but also other competencies in Figure 6 related to client-centered problem solving and good judgment and an entrepreneurial mindset to serve clients and legal employers in changing markets that flow from internalizing deep responsibilities to others, especially the client); and

2. The importance of a student proactively taking ownership of the student’s own professional development, using both the formal curriculum and professional experiences outside of the formal curriculum, to develop toward later stages of the competencies that are the student’s strengths, and to have evidence of the student’s later stage development that legal employers will value.

The second step for the law school is to communicate to students, in language and with concepts that they understand, how most effectively to use the bridge that the law school’s curriculum and culture create for each student. We cannot state enough the importance of Principle 3 from Chapter 4: Go Where They Are. Take into account that students are at different developmental stages with respect to the two key steps just noted.

The authors’ experience is that many students need substantially more help than might be expected to grow to understand the bridge and to become proactive in using their time in law school to achieve their postgraduation goals. A number of factors appear to contribute to the difficulty. Many students want to be told what to do, a posture consistent with how they experienced their education before law school. As William Henderson has noted, law students expect to learn about their law school subjects in standard ways. The emphasis of the 1L year curriculum on cognitive competencies, moreover, means that students go relatively unexposed to the fact that the practice of law calls for a much broader array of competencies than the knowledge of legal doctrine and the performance of legal analysis.Footnote 34 As noted earlier in the discussion of Principle 3 in Chapter 4, many students also are at an earlier stage of development on self-directed learning, and they are inexperienced at purposive planning of their development as a professional.Footnote 35 Indeed, the authors’ experience is that nearly all students, including highly ranked students, need substantial help in framing an effective persuasive argument for themselves that their strengths meet a particular employer’s needs (in the language of the employer) and that the student has evidence of this later stage development that the employer will value.

The law school’s curriculum and culture, from orientation through the remaining three years, can be used more effectively to help each student see and use the bridge, meeting them where they individually are developmentally. One powerful step in this direction would be for as many faculty as possible from all roles and ranks, whether doctrinal/podium or experiential, to make transparent to students the entire map of competencies needed to practice law, and to make explicit what competencies the student is learning in the course or in a particular experience. All faculty can emphasize the importance of the habits of seeking feedback and reflecting (Principle 4 in Chapter 4). This is particularly important, as Principle 6 in Chapter 4 emphasizes, at major transition points from being a student to being a lawyer where the student has engaged in authentic professional experiences (for example, immediately after summer internships or clerkships, and in conjunction with externships, clinics, lawyering skills courses, and simulation courses). Doctrinal/podium faculty may not feel fluent in such matters, but it is especially important that students hear their voices speaking to the importance of the law school’s professional development and formation initiatives. Even when a faculty member does not personally focus on formation-oriented competencies in a course, the professor can still endorse their significance and underscore how those competencies are addressed elsewhere in the school’s academic program. Such “cross-selling,” as we have called it, is quite easy, especially if faculty are provided talking points.

Principle 5 in Chapter 4 emphasizes coaching as the most effective curriculum to foster each student’s guided reflection and guided self-assessment, in major part because it is individualized to each student’s stage of development. Coaching is a particularly important strategy for Generation Z, the cohort group born after 1995, now applying to and enrolled in law school. Empirical data indicate that Generation Z prefers timely and frequent feedback that is future oriented, and not just an assessment of past performance. They want personal contact with managers and team members, and they are high on self-directed learning.Footnote 36 They prefer and respond best to coaching when the coach and coachee both play an active role in the developmental process.Footnote 37 A law school that leads in offering a curriculum of continuous coaching will be very attractive to Generation Z applicants and students.

Principle 6 in Chapter 4 emphasizes the importance of authentic experiences and communities of practice in the growth process from being a student to being a lawyer. The law school should do all it can to create communities of practice between the students and the school’s alumni and supportive practitioners, thereby affirming the importance of the school’s efforts to connect the students’ goals with client, legal employer, and legal system needs. Although senior lawyers and judges may be rightly celebrated, they may be many developmental stages removed from the student. Choose graduates and practitioners closer to the students in age and experience. Students will be able to more easily visualize the steps immediately ahead of them in professional growth.

5.9 Go Where the Legal Employers, Clients, and Profession Are and Build a Bridge Demonstrating That the Law School’s Graduates Are at a Later Stage of Development on the Competencies Employers, Clients, and the Profession Need

The previous practical suggestion focused on bridging students to PD&F goals with awareness of the personal goals that students have and purposeful, effective communication. We now turn our attention to the law school’s communication with legal employers, clients, and the legal profession. The law school can build a bridge to them too, helping them recognize that the law school’s graduates are reaching later stages of development on the competencies that employers, clients, and the profession need.

One illustrative – and perhaps less obvious – bridge to legal employers and clients could focus on the fact that legal employers currently are dramatically increasing attention to diversity and to DEI and Belonging initiatives. These initiatives drive at the same PD&F competencies that many law schools are choosing to spotlight. An entrepreneurial law school will educate the employers who hire the school’s graduates about both the law school’s efforts to foster each student’s growth toward later stages of these PD&F goals that employers need and how this broader understanding of the competencies needed to serve clients well (beyond just the standard cognitive competencies and ranking students cognitively) will increase the legal employers’ diversity. The law school can provide reliable evidence to the employers of each student’s later stage development of these needed competencies.Footnote 38 An entrepreneurial law school emphasizing the full range of competencies that legal employers need will give particular emphasis to DEI and Belonging initiatives that help historically underserved students understand the entire range of needed competencies and to create and implement a plan to develop those competencies.

A second illustrative bridge to employers and clients – and the intuitively most obvious bridge – would focus on the competencies that research indicates are needed by employers and clients and ensure that the school’s PD&F goals well align with those competencies. Empirical research on the competencies legal employers and clients need is getting stronger each year, and a law school should keep up with it and be conversant in it. Figure 6 earlier in this chapter represents a current synthesis of these empirical data, but there will be improving data. Appendix A to Chapter 1 has the current data. A law school should periodically compare its learning outcomes with the latest empirical data on the competencies needed and revise and adjust the learning outcomes as appropriate.

The most serious present gap between the competencies clients and legal employers need and the learning outcomes being adopted (see Table 24) is that few law schools have adopted strong client-service orientation learning outcomes on competencies such as superior client focus, responsiveness to the client, and an exceptional understanding of the client’s context/business.Footnote 39 It may be that the 13 percent of schools (from Table 24) with a client interviewing or counseling learning outcome will incorporate elements of strong client-service orientation. To the degree possible, a school should use the language of the clients and legal employers in formulating the school’s learning outcomes. This will help the students communicate a value proposition to clients and legal employers in a language these stakeholders can understand. A client interviewing and counseling learning outcome, for instance, could be revised to include fostering student growth toward a strong client-service orientation.

Two law schools have taken steps that others might find instructive. The University of Minnesota Law School adopted a learning outcome that graduates will demonstrate “client-oriented legal service, including the ability to: … (ii) listen to and engage with clients to identify client objectives and interests, and … (iv) counsel clients by assessing, developing, and evaluating creative options to meet client goals.”Footnote 40 Villanova’s Charles Widger School of Law adopted a strong learning outcome emphasizing understanding of the client’s context/business and an entrepreneurial mindset to serve clients and legal employers in changing markets.Footnote 41 Villanova’s Learning Outcome 8 provides the following:

Graduates will understand the importance for their career development of embracing an entrepreneurial perspective and cultivating the ability to manage and develop client and professional relations.

1. Graduates will possess competency in professional networking.

2. Graduates will possess basic fluency in business concepts and terminology used in the operation of diverse legal practices, including law firms, legal departments, and legal service organizations.

3. Graduates will demonstrate an understanding of business and financial considerations that affect (i) a client’s selection of a legal service provider and (ii) a legal service provider’s business and delivery model.

4. Graduates will recognize that new laws and technologies, as well as persistent problems and unmet needs, present opportunities for lawyers in the public, private, and non-profit sectors to harness their training and experience to forge new structures, organizations, products, services, and solutions.

Empirical data on how new lawyers most often “fail” as associates would be helpful to law schools that wish to formulate learning outcomes reflecting client and legal employer needs. Little such data currently are available. As an initial step to address that lack of data, one of the coauthors, Professor Hamilton, interviewed ten experienced attorneys at medium to larger firms in Minnesota during the summer of 2019, asking what are the major reasons that associates fail to progress in the firm. The lawyers all mentioned a version of two major reasons:

1. In the initial years as an associate, a failure to understand and internalize that the experienced lawyers giving the associate work are in effect “the internal clients.” Some associates continue to act like a student, doing the assigned work well, but not growing: (1) to internalize superior client focus/responsiveness to client (the internal client giving the work); (2) an exceptional understanding of the client’s context and business (the internal client’s context and business); and (3) an entrepreneurial mindset to serve the internal client in changing markets including an emphasis on greater efficiency in producing legal services.Footnote 42

2. In the later years as an associate, a failure to demonstrate the same competencies with respect to external clients. Of particular significance is a more senior associate’s failure to be proactive in creating and implementing a plan of client development using these client service orientation and entrepreneurial mindset foundational competencies.

Susan Manch, recently retired chief talent officer at Winston and Strawn (a firm with approximately 1,000 lawyers) recently outlined her similar experience on why associates fail. The chief reasons she cites for an associate’s failure are that the associate is (1) not client focused, (2) not entrepreneurial, (3) lacks commitment to grow, (4) does not add value, and (5) focuses solely on hours.Footnote 43

Entrepreneurial law schools will build a bridge proactively to connect with legal employers whom their graduates serve and signal the law school’s emphasis on the full range of competencies the employers need. The school also will provide employers with good evidence that its graduates are at a later stage of development on the needed competencies. Historically law schools have not provided strong evidence that an employer can rely upon to indicate that a student is at a later stage of development on the full range of competencies beyond the standard technical competencies of legal knowledge, legal analysis, legal research and legal writing. Note that for many of these additional competencies, practical experience observed by an experienced practicing supervisor has the most influence. The Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System’s 2016 study (with responses from 24,000 lawyers) noted early in Appendix A to Chapter 1 asked respondents what criteria were most helpful in the decision to hire an attorney. Table 25 has the thirteen most helpful criteria.Footnote 44

Table 25 The thirteen most helpful hiring criteria for employers hiring students for postgraduation employment

| Hiring Criteria |

Percentage of Respondents Answering “Somewhat Helpful” or “Very Helpful” |

|---|---|

| Legal employment | 88.3% |

| Recommendations from practitioners or judges | 81.9% |

| Legal externship | 81.6% |

| Other experiential education | 79.4% |

| Life experience between college and law school | 78.3% |

| Participation in law school clinic | 77.3% |

| Law school courses in a particular specialty | 70.3% |

| Recommendations from professors | 63.3% |

| Class rank | 62.5% |

| Law school attended | 61.1% |

| Extracurricular activities | 58.7% |

| Ties to a particular geographic location | 54.3% |

| Law review experience | 51.2% |

While the IAALS survey found that all the criteria were helpful in making a hiring decision, the six most helpful were all related to practical experience where an experienced supervisor has seen the work. In building a bridge to employers, entrepreneurial law schools can ask employers their graduates serve about the most important competencies they need in new lawyers and what evidence the employers would value indicating that a law student was at a later stage of development on the needed competencies. Schools also can work with employers on how to assess new lawyer development of the needed competencies, and also work with them on the use of effective behavioral interviewing strategies.