In Chapter 2, we introduced a framework of purposefulness to guide law schools in their efforts to help each student understand, accept, and internalize the four PD&F goals:

Ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need;

a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client;

a client-centered, problem-solving approach and good judgment that ground the student’s responsibility and service to the client; and

well-being practices.

The purposefulness framework offered in Chapter 2 can assist faculty, staff, and administrators at any law school, including a school adhering to the most traditional practices of American legal education. Many signs suggest, however, that competency-based education will take hold in legal education as it has in other areas of education. We therefore set out in Chapter 3 what a purposefulness framework would look like in law schools that adopt a robust competency-based approach. Medical education already has traveled far with such an approach, and Chapter 3 drew from our peers in medicine for knowledge and practices to emulate. Importantly, those lessons and practices also can inform and shape the initiatives that law schools might take even while not subscribing to a competency-based approach.

We now turn in this and the next chapter to the practical business of doing good work in your law school. We are presupposing that our readers are faculty, staff, and administrators who want their law school to have a purposeful, effective, well-conceived, and well-developed program supporting students in the pursuit of their PD&F goals. We presuppose that progress will take time. Some schools might blueprint comprehensive initiatives at the outset, but most will proceed incrementally.

Whether one is at the drawing board devising a complete program or instead looking to create only a solid pilot project focusing on a small aspect of a select PD&F goal, getting started and proceeding in a purposeful fashion is the most important thing. And regardless of the scope of your particular undertaking, there are concrete principles that you can keep in mind to strengthen your work and keep it headed toward the development – in the fullness of time – of a solidly built PD&F curriculum. We see ten such principles, and they are set out in this chapter. We maintain the practical focus in Chapter 5 and draw into view the realities of trying to bring about this kind of change in the law school. We are optimistic that it can be done and offer nine practical suggestions in Chapter 5 for your consideration.

The ten principles that we will explore in this chapter are synthesized from the literature that casts light on professional identity formation and its support: (1) the five Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching studies of higher education for the professions, (2) scholarship on higher education generally, (3) work in moral psychology, and (4) the literature on medical education’s increased attention to professional identity formation.Footnote 1 For convenience, let us state all ten principles:

Principle 1 Milestone Models Are Powerful Tools

A Milestone Model can significantly strengthen efforts to support student pursuit of a PD&F goal. Work toward agreement on a model should be encouraged.

Principle 2 Sequenced Progressions of Curriculum and Assessment Modules Are Powerful Tools

A sequenced progression of supported experiences, with corresponding assessments, enables effective, purposeful pursuit of a PD&F goal. Work toward development of a progression should be encouraged.

Principle 3 Go Where They Are

Students are at differing developmental stages of growth on any particular goal. Each student needs to be engaged at the student’s actual stage of development.

Principle 4 Reflection and Self-Assessment Are Powerful Tools

Repeated opportunities for guided reflection and guided self-assessment foster a student’s growth to the next stage on any PD&F goal. Try to provide them.

Principle 5 Mentoring and Coaching Are Powerful Tools to Be Combined

Continuous one-on-one mentoring and coaching is the most effective pedagogy to foster each student’s guided reflection and guided self-assessment. Try to provide it.

Principle 6 Major Transitions Are Pivotal to Development – and Major Opportunities for Support

Coaching to foster guided reflection and guided self-assessment can be especially effective at points when the student experiences a major transition on the path from being a student to being a lawyer. Pay special attention to major transitions.

Principle 7 Connect Professional Development and Formation to the Student Personally

Assist each student to see how new knowledge, skills, and capacities relating to PD&F goals are building on the student’s existing knowledge, skills, and capacities and are helping the student achieve the student’s postgraduation bar passage and meaningful employment goals.

Principle 8 Think Very Differently about Assessment on PD&F Goals

Combine guided self-assessment with direct observation and multi-source feedback and assessment by faculty and staff.

Principle 9 Student Portfolios Can Help Students Progress

Consider calling upon each student to create a personal portfolio on any one of the four PD&F goals, including an individualized learning plan to develop to the next level of growth.

Principle 10 Program Assessment on PD&F Goals Becomes Clear and Manageable if Principles 1 through 9 Are Heeded and Implemented

Progress on Principles 1 through 9, and particularly on Principles 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, and 9, will substantially support program assessment as required by ABA Accreditation Standard 315.

These ten principles may seem daunting, particularly to people new to thinking about professional identity formation support. We urge you to not consider them rules that must be followed, or steps that must be taken. Do not let aspirations toward perfection become the enemy of the good. As you undertake your work, draw on the principles to the extent that they are helpful to you. In time and with accrued experience, the value of the principles likely will become increasingly apparent, and the principles themselves something of second nature to your thinking. Let them guide you, not govern you.

4.1 Principle 1 Milestone Models Are Powerful Tools

A Milestone Model can significantly strengthen efforts to support student pursuit of a PD&F goal. Work toward agreement on a model should be encouraged.

Efforts to support students in the development of a competency can profit greatly from a Milestone Model, as Chapter 3 explained. A principal challenge for faculty and staff with respect to the PD&F goals is that, unlike a traditional learning outcome like legal analysis, the faculty and staff do not have a clear shared understanding to define the level of competence a student must achieve and the stages of development to get there. A good Milestone Model draws the particular competency at issue and its stages of development into view, enabling more purposeful and effective work at every step by everyone involved. A law school’s work toward reaching reasonable agreement on a Milestone Model on any PD&F goal it adopts will return immediate dividends with better realization of the goal. Longer-term dividends are in the offing too. The school can build on its experience in reaching agreement on a first Milestone Model to establish models for other PD&F goals. Simply put, a Milestone Model is a powerful tool for ensuring purposefulness.

Nearly all law schools already have taken the first step toward a Milestone Model. In keeping with ABA accreditation standards, faculty and staff must establish learning outcomes for the school. A critical next step – getting those outcomes in top shape for use in a Milestone Model – is easier than it might seem. In defining, reviewing, and revising learning outcomes for the law school, faculty and staff should keep abreast of the best empirical evidence defining the knowledge, skills, and capacities a new lawyer must develop to meet the needs of clients, legal employers, and the legal system. Appendix A to Chapter 1 has the most current data, and the Foundational Competencies Model presented in Figure 1 in Chapter 1 synthesizes all these data into a framework students can visualize and understand, structured on the four foundational PD&F goals.Footnote 2

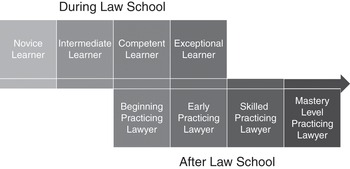

The next step toward a Milestone Model is to embrace the idea that a student begins development of professional competencies in law school and progresses in stages of development on these same competencies well into professional life after law school. The idea is well depicted in Figure 5, which shows the competency alignment model that the Holloran Center has developed.

Figure 5 Holloran competency alignment model showing the stages of development of learning outcome competencies: A continuum from entry into law school throughout a careerFootnote 3

In simplest terms, a Milestone Model for a particular competency details what it means for the student or lawyer to be “at” the various respective stages of development depicted in Figure 5.

From this point on, devising a Milestone Model depends greatly on the particular competency; what progressive development toward mastery of the particular competency entails; and how the student’s progress through stages can be fostered, evidenced, and assessed. With stages carefully identified, the school can better consider how student movement from stage to stage can be supported with experiences, coaching, reflection, and assessment.

Note that the Milestone Model associated with any PD&F goal can be aligned well with the models that legal employers are using to assess their lawyers on the same competency. The school’s learning outcomes and curriculum thus will meet employer and client needs, and students will be able to communicate their value to potential employers using the employers’ language.

What might Milestone Models for each of the four PD&F goals look like? Examples are presented and explained in Appendix B. We encourage readers to examine them. They will give the reader a good sense of what Milestones can look like in legal education. They can be followed or adapted and can serve as inspiration for other models. Even if your school is not ready to take such steps, familiarity with these examples can help inform and advance discussions within the law school about how to best support and assess student development.

4.2 Principle 2 Sequenced Progressions of Curriculum and Assessment Modules Are Powerful Tools

A sequenced progression of supported experiences, with corresponding assessments, enables effective, purposeful pursuit of a PD&F goal. Work toward development of a progression should be encouraged.

Milestone Models make clear that each student is going to be at a novice, intermediate, competent, or exceptional learner stage on a particular PD&F goal. The law school’s faculty and staff want to help each student grow to the next stage of development. Suppose the PD&F goal at issue is one that the school has set as an institutional learning outcome – more than 30 percent of all law schools, for example, have adopted an institutional learning outcome on self-directed learning. Efficient and effective support for the student’s progress means offering the experiences, coaching, feedback, opportunities for reflection, knowledge, and information that are targeted to help the student progress to each successive stage. Well-conceived curriculum and assessment modules do just that. Devising good modules requires a wide-angle view of the student’s experiences, as many important steps in a student’s formation of professional identity occur outside the traditional classroom curriculum – in cocurricular and extracurricular activities, in engagements with career services, and in summer and other outside experiences. Faculty and staff should work together as co-educators in a whole building approach as outlined in Chapter 2 so that each student experiences a sequenced and coordinated progression of curriculum and assessment modules that foster the student’s growth to the next stage. In our example, faculty and staff might coordinate their efforts over time to build curriculum modules – identified experiences and the supporting pedagogy and assessment modules focusing on self-directed learning throughout the three years of law school.

A way to begin is by mapping the existing required curriculum to identify modules that currently offer experiences that foster (and assess, or could assess) student growth regarding the goal. Are the modules coordinated and building on each other? Are there gaps in a logical sequence of modules to foster each student’s growth? Over time, adjustments and additions can be made to develop a coordinated progression with no significant gaps.

It is important to note that while each competency has its own stages of development, the competencies also build on one another. Some competencies form the building blocks for the development of other competencies. Figure 2 in Chapter 2 outlines this progression of competencies. Figure 2 provides guidance on how to structure a curriculum to foster each student’s competencies in Group 1, then Group 2, then Group 3, then Group 4, and then Group 5. To be sure, flexibility and creativity will be rewarded in this work, and efficiencies can be captured. Because competencies build on one another, more than one competency can be the focus of a particular module.

4.3 Principle 3 Go Where They Are

Students are at differing developmental stages of growth on any particular goal. Each student needs to be engaged at the student’s actual stage of development.

Considering each student’s developmental stage on a particular competency and engaging the student at the appropriate stage are emphasized in the Carnegie studies of higher education in the profession,Footnote 4 scholarship on moral psychology,Footnote 5 scholarship on how learning works in higher education,Footnote 6 and scholarship on medical education.Footnote 7 We emphasized the same point when setting out the core components of competency-based legal education in the preceding chapter (Table 13 in Chapter 3). Teaching must be individualized to the learner, based on the abilities required to progress to the next stage of learning.

The authors and others have been experimenting with teaching to help students toward PD&F goals in both the elective and the required curriculum for many years. Elective courses on these goals draw “the choir” from the student body who are very interested in personal and professional growth toward later stages of development on these outcomes. Designing elective PD&F courses is challenging, but the authors have had outstanding favorable student responses to these courses.

Designing a required PD&F course is far more challenging because students present a much broader spectrum of developmental stages. Keeping with our previous example of a school that is focusing on the goal of self-directed learning, for instance, earlier-stage students on self-directed learning tend to be passive and are unlikely to take courses that create cognitive dissonance around ownership of professional development or the integration of responsibility to others. A school that sets self-directed learning as an institutional learning outcome sensibly will conclude that a required course is necessary to reach these early-stage students. The authors’ experience, however, is that instructors who intentionally create cognitive dissonance in a required course to foster growth toward PD&F goals are going to get some student pushback.

The breakthrough thinking in recent years has been to “go where they are.” This means designing curriculum that reflects stage-appropriate engagement for each student. Experimentation is required, packaged and delivered with a great deal of humility, and followed by responsive adjustments. A common mistake has been to create engagements that appeal to students at later stages of development but do not appeal to earlier-stage students. This can be the case, for instance, when mentoring is employed. Mentoring a student on PD&F goals can be very powerful, and later-stage students tend to utilize mentoring well. Earlier-stage students, however, stay too passive to benefit as greatly from the mentoring. Experience suggests that one-on-one coaching in the required curriculum is more effective for these more passive students than mentoring alone – a point explored further in Principle 5.

The principle of “going where they are” has further valuable implications, pointing the way to how to encourage greater student engagement with all their PD&F goals and the school’s efforts to support their development. The experience of the authors suggests that many students in required courses need much more help than expected “to connect the dots” – to see the relationships between their goal of meaningful employment, the competencies that legal employers and clients want, the faculty’s PD&F goals set in learning outcomes, and the actual curriculum. One study, for example, reports that 50 percent to 60 percent of the first-year and second-year students surveyed were self-assessing at one of the two earlier stages of self-directed learning.Footnote 8 Many also may need much more help in creating a narrative of strong competencies that legal employers and clients want. The enlightened interest of the student marks an entry point for the law school’s PD&F support work. The curriculum should help each student understand clearly how progressing in the development of PD&F goals will help the student attain the goal of meaningful postgraduation employment – and how the curriculum and assessment modules employed by the school serve that end each step of the way. Discussion in Chapter 5 will address how to build bridges that connect PD&F goals and their curriculum and assessments to the enlightened self-interest of students, and other stakeholders as well.

4.4 Principle 4 Reflection and Self-Assessment Are Powerful Tools

Repeated opportunities for guided reflection and guided self-assessment foster a student’s growth to the next stage on any PD&F goal. Try to provide them.

The five Carnegie studies of higher education for the professions call out the importance of “fostering each student’s habit of actively seeking feedback, dialogue on the tough ethical calls, and reflection.”Footnote 9 Scholarship in moral psychology also emphasizes fostering each student’s reflective judgment and providing repeated opportunities for reflective self-assessment through the curriculum.Footnote 10 The professionalism award winners in the Minnesota bar in Neil Hamilton and Verna Monson’s study of exemplary lawyers emphasized the importance of the habit of ongoing reflection and learning in their career-long development toward later stages of all four PD&F goals.Footnote 11 Medical education research similarly underscores the importance of fostering each student’s habit of reflection on experiences.Footnote 12 The Council of the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions recent revisions to Standard 303 emphasize that “[b]ecause developing a professional identity requires reflection and growth over time, students should have frequent opportunities during each year of law school and in a variety of courses and co-curricular and professional development activities.”Footnote 13

Reflection and self-assessment are powerful tools that should figure prominently in a student’s development through the stages of any PD&F goal. Indeed, the competency to reflect and self-assess is itself a foundational professional skill, as illustrated in Tables 19 and 20 in Appendix B. There the reader will find Milestone Models for each of the first two PD&F goals. Both include the foundational sub-competency of reflection. In assessing, for instance, a student’s development toward Goal 1 – ownership over the student’s continuous professional development (self-directedness) – the model calls for assessing whether the student “seeks experiences to develop competencies and meet articulated goals and seeks and incorporates feedback received during the experiences” and “uses reflective practice to reflect on performance, contemplate lessons learned, identify how to apply lessons learned to improve in the future, and applies those lessons.”

Defining the sub-competencies of reflection is challenging because it is a complex construct and there has been a lack of consensus on its definition.Footnote 14 The strongest definition in a professional context comes from medical education in a paper authored by Dr. Quoc Nguyen and others.Footnote 15 It is helpful to introduce that definition here to illustrate how to begin thinking about supporting reflection and self-assessment. Based on a systematic review of the most cited papers on reflection in the period 2008 to 2012, the authors defined reflection as “the process of engaging the self in attentive, critical, exploratory, and iterative interactions with one’s thoughts and actions, and their underlying conceptual frame, with a view to changing them.”Footnote 16 This conceptual model of reflection has two extrinsic elementsFootnote 17 and four core sub-competencies.Footnote 18 The first extrinsic element is an experience that triggers a reflective thinking process.Footnote 19 The second extrinsic element is the timing of the reflection. In the vast majority of definitions of reflection, the timing occurs after the experience, but Nguyen and coauthors believe reflection should occur before, during, and after the experience.Footnote 20

The four core sub-competencies (or steps) of a reflective thinking process are (1) to identify specific thoughts and actions the person is thinking about; (2) to think about the thoughts and actions attentively and critically, in an exploratory and iterative fashion; (3) to become aware of the conscious or unconscious conceptual framework(s) that underlie the person’s thoughts and actions; and (4) to have a purpose of changing the self in terms of the person’s conscious or unconscious conceptual framework.Footnote 21 The curriculum should provide multiple opportunities for students to develop the habit of engaging in this reflective thinking process.Footnote 22 Appendix D for Chapter 4, has both a Milestone Model on the competency of reflection and a Milestone Model to grade an individual reflection assignment.

Students benefit greatly from coaching to guide this reflective thinking process. The findings of a meta-study of empirical research on teaching interactions in medical education emphasizes that “it is important for students to receive some assistance in navigating the complexity of reflection, and students benefit from learning about reflection through introductions, guidelines to writing, and receiving feedback on their work.”Footnote 23 The literature also points to the role of a mentor/coach as essential for scaffolding medical students’ reflections.Footnote 24 We turn to the importance of mentoring and coaching next, as it is embraced in our fifth principle.

4.5 Principle 5 Mentoring and Coaching Are Powerful Tools to Be Combined

Continuous one-on-one mentoring and coaching is the most effective pedagogy to foster each student’s guided reflection and guided self-assessment. Try to provide it.Footnote 25

Guided reflection and guided self-assessment are critical contributors to a student’s successful progressive growth on any PD&F goal. The growth process will entail numerous experiences – including professionally authentic experiences that can be particularly valuable – occurring in a coordinated sequence of modules that rationalize the student’s stage development toward the goal. What pedagogy best supports the student’s guided reflection and guided self-assessment throughout that progression? A one-on-one continuous mentoring/coaching model stands out as most conducive to effective support. This model affords additional benefits that law school faculty and staff will find attractive; we will address those benefits later. First, we will explore what the literature tells us about mentoring and coaching. Many who enter the work of supporting law student professional-identity formation will take on the role of a mentor or coach, perhaps even without knowing it. Awareness of what it means to take on those roles, and to do them well, will prove useful. An individualized one-on-one continuous mentoring/coaching model to provide guided student reflection and assessment is supported by leading scholars. Ida Abbott, a scholar on mentoring in the legal profession, points out that the lines between mentoring and coaching are fluid because both roles “provide individualized and personal support by a trusted advisor.”Footnote 26 She also notes that “[a]s coaching becomes more popular, boundaries between mentoring and coaching will blur and overlap.”Footnote 27 Regarding mentoring, earlier scholarly literature spoke of a “career mentoring function” that directly aided the protégé’s career advancement.Footnote 28 Taking a historical perspective, Abbott has defined mentoring to be “a relationship-based process that helps individuals learn, grow and achieve high levels of professional success and fulfillment,”Footnote 29 adding “[m]entoring occurs when a more experienced and trusted lawyer takes an interest in an individual’s career development and success.”Footnote 30 Mentors have relevant work and career experience, provide career and psychological support, and can create or directly affect career-enhancing opportunities.Footnote 31

Regarding coaching, Abbott explains that coaches help individuals “uncover personal and professional goals, develop a plan to achieve those goals, and provide ongoing support while the plan is implemented.”Footnote 32 Coaches are trained to “listen, ask powerful questions, serve as a sounding board, motivate and hold accountable the people they work with”;Footnote 33 “[c]oaches do not need to be lawyers (although they often are) because coaching employs a process where they are not offering advice or conveying substantive information.”Footnote 34 Coaches help lawyers create plans and develop strategies for career advancement.Footnote 35 In Abbott’s analysis, “[a] major advantage that mentors have over coaches in law firms concerns career advancement.”Footnote 36 Abbott compares mentoring and coaching in Table 15.

Table 15 Comparison of mentors and coachesFootnote 41

| Mentor | Coach | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary function | Career support, psychological support | Goal achievement, performance |

| Focus | Professional development | Functional improvement, results |

| Audience | All lawyers | High-potential and under-performing lawyers |

| Attributes | Willing/able to model, advise, support, transfer knowledge | Trained in coaching techniques |

| Level of intensity | Moderate | Moderate |

| Level of trust required | Moderate–high | Moderate |

John Whitmore, author of the first book on workplace coaching,Footnote 37 defines coaching as “unlocking people’s potential to increase their own performance. It is helping them to learn rather than teaching them.”Footnote 38 Coaching supports people “to clarify their purpose and vision, achieve their goals, and reach their potential.”Footnote 39 Whitmore believes mentoring is more about sharing expertise and passing down knowledge with some guidance.Footnote 40

Coaching focuses on developing a student’s self-understanding and discernment of purpose, vision, and goals, and the student’s self-direction as manifested in the creation and implementation of a plan to achieve the student’s vision and goals. Mentoring emphasizes relationship-based career support for students by mentors with relevant work and career experience who use their own experience, insight, and advice to help mentees learn and progress.

Consideration of two of our PD&F goals will illustrate the value of coaching and mentoring. To grow to the next level of the first PD&F goal – ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need – a student needs coaching situated in the context of the student’s own path in the legal market and the student’s own development. The student also needs mentoring that helps the student become more familiar with the legal market and how to navigate within it toward success in a career. To grow to the next level of the second PD&F goal – a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client – a student needs mentoring that illuminates how professional skills are used to forge and maintain relationships with clients that serve the clients’ needs. Yet each student also needs coaching to develop and implement a plan to achieve the needed growth to the next level.

Abbott emphasizes that mentors must themselves have proven legal skills and ownership over continuous professional development to be effective.Footnote 42 Mentors facilitate a mentee’s learning by helping mentees process what they are observing and experiencing and then apply what the mentees have learned to different circumstances.Footnote 43 Mentors actively listen to their mentees, show empathy,Footnote 44 and give meaningful feedback.Footnote 45 They build mentee confidenceFootnote 46 and counsel on career development and career advancement issues.Footnote 47

Workplace coaching is still an emerging profession.Footnote 48 There is very little legal scholarship on coachingFootnote 49 even though larger law firms are increasingly using coaching to help individual lawyers learn specific professional skills.Footnote 50 There is, however, some scholarship about the most important competencies for professional coaching generally. The International Coaching Federation (ICF) has accredited more than 30,000 professional coaches worldwide.Footnote 51 ICF released an updated Coaching Core Competencies Model in October 2019 based on evidence collected from more than 1,300 professional coaches.Footnote 52 The ICF identifies eight core professional coach competencies. The professional coach

1. Demonstrates ethical practice including confidentiality;

2. embodies a coaching mindset including ongoing reflective practice and ongoing development as a coach;

3. establishes and maintains clear agreements for the overall coaching engagement with the client;

4. cultivates trust and safety with the client including understanding and respecting the client’s context and identity and support, empathy, and concern for the client;

5. maintains presence including being fully present with and responsive to the client;

6. listens actively;

7. evokes client awareness, insight, and learning by using tools such as powerful questioning, silence, metaphor, or analogy; and

8. facilitates client growth by transforming learning and insight into goals and action.Footnote 53

John Whitmore’s model of workplace coaching, advanced in his groundbreaking book now in its fifth edition, has been influential. Whitmore argues that “by and large, [coaches] subscribe to a common set of principles.”Footnote 54 He lists three fundamental skills of coaching:

1. Asking powerful open questions to raise the coachee’s awareness and responsibility.Footnote 55

a. “Awareness” includes:

(i) awareness of self – understanding why you do what you do;

(ii) awareness of others – knowing other people’s strengths, interferences, and motivations; and

(iii) awareness of the organization – aligning individual, team, and organizational goals.Footnote 56

b. “Responsibility” is taking ownership of the coachee’s own development and high performance, and committing to action.Footnote 57

2. Listening well.Footnote 58 Whitmore defines listening well as active listening and includes a table of active listening sub-competencies.Footnote 59

3. Following the GROW model with respect to the sequence of questions.Footnote 60

– Goal-setting for the session as well as the short and long term (What do you want?);

– Reality checking to explore the current situation (Where are you now? And what blocks your path?);

– Options and alternative strategies or courses of action (What could you do?); and

– What is to be done, when, by whom, and the will to do it (What will you do?).Footnote 61

Whitmore emphasizes that the key to using the GROW model is to spend sufficient time asking questions exploring goals “until the coachee sees a goal that is both inspirational and stretching to them, and then to move flexibly through the sequence according to [the coach’s] intuition, revising the goal if needed.”Footnote 62 Whitmore also emphasizes asking open questions that generate awareness and responsibility. While coaching is not all about asking questions, that is the single most important skill to master for a novice coach.Footnote 63 Whitmore provides a “Coaching Question Toolkit” containing questions that experienced coaches have found consistently helpful in coaching:Footnote 64 “The golden rule is to be clear and brief. Sometimes the most powerful questions lead to a long silence so the coach should not feel the need to jump in with another question if there is a long pause.”Footnote 65

The ICF core coaching competencies, the Whitmore fundamental coaching skills, and Abbott’s mentoring skills emphasize similar foundational skills. We draw from and elaborate upon them in Table 16 to offer a list of foundational competencies for the mentor/coach in the law student context.

Table 16 Foundational competencies for a law student mentor/coach

| 1. | Actively listening to understand both where the student is developmentally and what are the student’s goals; |

| 2. | Asking powerful open questions to foster the student’s guided reflection and guided self-assessment and raise the student’s awareness and responsibility; |

| 3. | Facilitating student growth toward later stages of the PD&F goals by transforming learning (especially learning in authentic professional experiences) and insight into clear and realistic goals, options, and action;Footnote 67 and |

| 4. | Understanding and respecting the student’s context and identity and providing support, empathy, and concern for the student. |

Empirical evidence shows that coaching in a 45- to 60-minute interview to promote student reflection with respect to self-directed learning is effective and can have an important and lasting impact on a student.Footnote 66 In a study of 102 undergraduates (with a mean age of 21), a trained interviewer conducted a one-on-one in-person interview designed to promote reflection about the student’s purpose in life, core values, and most important life goals. The study included a pretest and a posttest nine months later to assess the impact of the interview.Footnote 68 On average, the coaching engagement led to benefits for student goal-directedness toward life purpose nine months later.Footnote 69 The author of the study suggests that these coaching conversations are “a triggering event [that] would impel an emerging adult, who is likely in this stage of life to be predisposed to identity exploration, to reflect on life beyond the interview in considering his or her life path.”Footnote 70 In general, individualizing students’ learning experiences, so the student can practice rather than just observe, and combining those individualized experiences with an instructor who provides continuous feedback to the student has been associated with more learning benefits than large group training with respect to self-directed learning.Footnote 71

The students’ ultimate goals are to pass the bar and find meaningful postgraduation employment. A mentor who has relevant work and career experience will have credibility with the students regarding the students’ goals. An experienced mentor/coach using the foundational competencies for law student coaching in Table 16 can foster each student’s growth toward later stages of the PD&F goals while helping the students achieve their goals.

It should be clear that the mentor/coach is putting Principle 3 into action by “going where they are” and engaging each student at the student’s present developmental stage. The mentor/coach is also observing Principle 4 by providing repeated opportunities, particularly at major transitions as discussed in the next principle, for guided reflection and guided self-assessment to foster each student’s growth to the next stage of a PD&F goal. The mentor/coach can help each student with self-assessment on the relevant Milestone Model for a particular learning outcome (contributing to fulfillment of Principle 1) and provide outside observer assessment concerning a student’s stage of development. The mentor coach can help each student create and implement a plan to move through a coordinated progression of modules to foster the student’s growth to the next level (contributing to fulfillment of Principle 2).

At the outset of our discussion of this principle, we noted that a model of synthesized mentoring and coaching offers additional benefits to the law school and its students. Many law schools today are undertaking diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives and student well-being initiatives. Positive student experiences with coaches and mentors can contribute to the goals of those initiatives. Recent empirical research on student well-being and DEI emphasizes the importance of “psychologically attuned interventions [that] emphasize a person-by-situation approach that is neither person-centric nor fully context-centric. In this approach, personal factors (e.g., law student social identities, such as race, gender, or social class) interact with societal stereotypes and environmental cues to shape thoughts, feelings, and behavior.”Footnote 72 The aim of these psychologically attuned interventions is to alter people’s process of making meaning and sense about themselves to change the interactions between people and contexts over time.Footnote 73 For example, “social-belonging interventions facilitate beliefs that may help students’ sense of belonging and psychological safety in the face of challenges.”Footnote 74 Growth mindset interventions change people’s process of making meaning with respect to one’s own and others’ abilities and potential to grow.Footnote 75 Individualized coaching will also foster student performance and well-being. Self-Determination Theory research shows that providing autonomy support to students where the teacher conveys understanding of the student and provides the student with choices increases the student’s ability to perform maximally, to fulfill psychological needs, and to experience well-being.Footnote 76

4.6 Principle 6 Major Transitions Are Pivotal to Development – And Major Opportunities for Support

Coaching to foster guided reflection and guided self-assessment can be especially effective at points when the student experiences a major transition on the path from being a student to being a lawyer. Pay special attention to major transitions.

Fostering each student’s guided reflection particularly at major transitions during law school is very important.Footnote 77 Each law student experiences significant transitions where the student is growing, step by step, from being a novice outsider with a stance of being an observer ultimately to join a community of practice as an insider to the profession.

There is a distinction between the situational changes a law student experiences and the significant transitions of law school. During law school, each student experiences a number of situational changes like physically moving to a new city to attend law school or starting a new class or a new year of law school. A significant transition, however, is a psychological inner reorientation and self-definition that the student must go through to incorporate the situational changes into a new understanding of professional life’s developmental process.Footnote 78 It is clear that the major periods of inner reorientation and self-definition for a law student are exceptional opportunities for the law faculty and staff to foster student growth toward later stages of the school’s learning outcomes.

Research on medical education emphasizes that a new entrant to a profession like medicine is growing, step by step, from being an outsider with a stance of an observer to joining a new group or “community of practice” as an insider in a profession.Footnote 79 Medical professors Lockyer, de Groot, and Silver explain:

Generally, transitions are critically intense learning periods associated with a limited time in which a major change occurs and that change results in a transformation. During transitions, people re-form their way-of-being and their identity in fundamental ways. Thus, transitions represent a process which involves a fundamental reexamination of one’s self, even if the processing occurs at a largely unconscious level. In transition periods, people enter into new groups or “communities of practice.” This involves adopting shared, tacit understandings, developing competence in the skilled pursuit of the practice, and assuming a common outlook on the nature of the work and its context.Footnote 80

These transitions are often characterized by anxiety, stress, and risk for the developing professional.Footnote 81 As medical professor Sternszus observes, “The literature supports the notion that transitions in medical education are both highly stressful and inadequately supported.”Footnote 82

A 2018 meta-analysis reviewed seventy articles on medical transitions to synthesize the evidence and provide guidance for medical education.Footnote 83 The focus on transitions and their importance is apparent. The authors found that the strongest empirical evidence asked medical faculties

1. To provide learning opportunities at transitions that include authentic (real-life or mimicking real-life) professional experiences that build progressively toward an understanding of principles. The authenticity of the learning becomes increasingly important as the learners become more independent.Footnote 84

Moderate to strong recommendations (i.e., supported by solid evidence from one or more papers plus the consensus of the authors of the article) were for medical faculties

2. To encourage progressive incremental independence by offering a sliding scale of decreasing supervision alongside demonstrating increasing trust in the student;Footnote 85

3. to apply concepts of graduated responsibility to nonclinical as well as clinical domains of training, such as leadership and responsibility;Footnote 86

4. to make trainees aware of the psychological impact of actual responsibility including the process of their own professional formation as they move up each level of training;Footnote 87

5. to establish a mentorship program with local champions to provide feedback to develop learners’ competence and confidence (supported reflection and discussion are important in the process of becoming an independent practitioner);Footnote 88 and

6. to seek to aid the development of resilience and independence.Footnote 89

How do law students themselves assess the important transitions in their journey from novice to competent learner/beginning practicing lawyer with respect to PD&F goals? To start answering this question, coauthor Professor Hamilton developed a Qualtrics survey for law students at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in September of the 2L year asking them to reflect on the transitions of the 1L year and the summer between the 1L and the 2L years.Footnote 90 The survey focused on transitions regarding ownership over continuous professional development (the stages are set forth in Table 19 in Appendix B). At St. Thomas, all 2Ls take Professional Responsibility in the 2L year, and sixty-two of the sixty-two students present in Hamilton’s Professional Responsibility class on September 6, 2018, filled out the survey. The survey question was: “In the context of the self-directed learning stage development model [in Table 19], what is the impact of each experience in this survey on your transition from thinking and acting like a student to thinking and acting like a junior lawyer?” The respondent could choose among the following: no impact, some impact, moderate impact, substantial impact, and great impact. There also was an opportunity for respondents to add additional experiences that were significant with respect to the survey question, but none of the added experiences was mentioned by more than a single respondent. Table 17 indicates the experiences that had the greatest impact.

Table 17 Experiences in the 1L year and the following summer that 50 percent or more of the students thought had a great, substantial, or moderate impact on their transition from thinking and acting like a student to thinking and acting like a junior lawyer with respect to ownership over continuous professional development

| Other Experiences | Percentage of the Students Answering Great, Substantial, or Moderate Impact |

|---|---|

| Summer Employment: most impactful experience | 89% (with 59% responding great impact) |

| Paid or unpaid summer employment experience | 87% (with 52% responding great impact) |

| Receiving graded memo from Lawyering Skills | 87% (with 19% responding great impact) |

| Final Examination Period (Fall Semester) | 87% (with 16% responding great impact) |

| Mentor Externship: most impactful experience | 85% (with 19% responding great impact) |

| Job Search for the Summer | 82% (with 14% responding great impact) |

| First Week of Classes | 81% (with 11% responding great impact) |

| Final Examination Period (Spring Semester) | 77% (with 19% responding great impact) |

| Oral Arguments for Lawyering Skills II | 76% (with 14% responding great impact) |

| Fall Midterms | 76% (with 10% responding great impact) |

| First CLE/Networking Events with Lawyers | 71% (with 10% responding great impact) |

| First Time Being Cold-Called in Class | 70% (with 13% responding great impact) |

| Spring Midterms | 67% (with 4% responding great impact) |

| Mentor Externship Experiences Generally | 64% (with 16% responding great impact) |

| Spring Semester Final Grades | 63% (with 27% responding great impact) |

| Roadmap Coaching | 60% (with 9% responding great impact) |

| Roadmap Written Assignment | 60% (with 4% responding great impact) |

| First Career and Professional Development (CPD) Meeting | 58% (with 2% responding great impact) |

| Orientation | 58% (with 3% responding great impact) |

| Fall Semester Grades | 55% (with 13% responding great impact) |

Table 17 makes clear that 2L students reflecting on the major transitions in the 1L year and the summer following the 1L year rate professionally authentic experiences (those that are real-life or mimic the real-life work of a lawyer) as having the greatest impact on their growth toward later stages of ownership of their own continuous professional development. A very high proportion of students rated their most impactful experience in summer employment (59 percent) and paid or unpaid summer employment generally (52 percent) as having a great impact on their transition from thinking and acting like a student to thinking and acting like a junior lawyer. The third most impactful experience was receiving back the first graded memorandum in their lawyering skills course (with 19 percent responding great impact), and the fifth most impactful experience was in a mentored externshipFootnote 91 (19 percent responding great impact). These, too, are professionally authentic experiences.

Paid or unpaid summer employment experience after the 1L year is a singularly important professionally authentic transition. Summer employment is outside of the formal curriculum, but the law school can and should provide some coaching and guided reflection for each student about the summer employment transition experience. It seems far too rich an opportunity to squander.

The major takeaway from Table 17 is that law schools should provide some curricular support at several significant transitions where students may also experience substantial stress, including particularly

1. Immediately after the summer employment experience;

2. immediately after major professionally authentic experiences like the first graded memorandum or an oral argument in a lawyering skills course; and

3. immediately after students receive fall semester grades and are considering summer employment.

There is a major need for further survey research on students in all three years of law school to identify more clearly the major transitions they experience. The authors’ best practical judgment on the major transitions in the 2L and 3L years is in Appendix C.

4.7 Principle 7 Connect Professional Development and Formation to the Student Personally

Assist each student to see how new knowledge, skills, and capacities relating to PD&F goals are building on the student’s existing knowledge, skills, and capacities and are helping the student achieve the student’s postgraduation bar passage and meaningful employment goals.

Adult learning theory emphasizes two themes that are important for faculty and staff seeking to support law students in the formation of professional identity:

(1) Students are more motivated to learn if they can see that the subjects are relevant to their goals;Footnote 92 and

(2) students learn most effectively when they are able to connect new knowledge and skills to prior knowledge and skills.Footnote 93

Students will better pursue their PD&F goals if they see how those goals connect to their own abilities and aspirations, and students need assistance to see those connections. Providing that assistance will heighten engagement and strengthen learning, and that is reason enough to undertake the effort. The “hidden curriculum” features of the typical law school environment only underscore the importance of providing assistance to students. Students often interpret the strong emphasis traditionally placed on the cognitive competencies associated with “thinking like a lawyer” as a signal that competencies having to do with professional identify formation are a low priority. The signal, though unintended, is an impediment to motivation and engagement with respect to PD&F goals.

How to make the needed connection? Understanding the personal goals of law students is essential, and there are good data. The 2018 Association of American Law Schools (AALS) report, Before the JD: Undergraduate Views on Law School, is the first large-scale, national study to examine what factors contribute to an undergraduate student’s decision to go to law school.Footnote 94 The AALS study is based on responses from 22,189 undergraduate students from twenty-five four-year institutions and 2,727 law students from forty-four law schools.Footnote 95 The survey asked the undergraduates, “How important are each of these characteristics to you when thinking about selecting a career?” The top three characteristics that undergraduate students considering law school thought were “extremely important” are

1. Potential for career advancement (selected by 62 percent of the respondents);

2. opportunities to be helpful to others or useful to society/giving back (selected by 54 percent of the respondents); and

3. ability to have a work-life balance (selected by 50 percent of the respondents).

Overall, a synthesis of the AALS data indicates the most important goal of undergraduate students considering law school is meaningful postgraduation employment with the potential for career advancement that “fits” the passion, motivating interests, and strengths of the student and offers a service career that is both helpful to others and has some work/life balance. A 2017 empirical study of enrolled 1L students in five law schools is consistent with this synthesis. The study asked, “What are the professional goals you would like to achieve by six months after graduation?” The two most important goals were bar passage and meaningful employment, followed by sufficient income to meet loan obligations and a satisfactory living.Footnote 96

Drawing on twenty years of empirical research on emerging adults in the age range 18 to 29, James Arnett finds that there is a very strong American consensus that becoming an adult means becoming self-sufficient, learning to stand alone as an independent person.Footnote 97 Three criteria are at the heart of emerging adults’ view of the self-sufficiency required for adulthood: (1) taking responsibility for yourself, (2) making independent decisions, and (3) becoming financially independent.Footnote 98

The curriculum on the four PD&F goals needs repeatedly to connect the dots so that each student sees that growing to a later stage on one of these learning outcomes helps the student reach their postgraduation goals. Chapter 1 outlined these benefits. Each student will need coaching on how to communicate in the language legal employers use for these competencies. The Foundational Competencies Model in Figure 1 of Chapter 1 provides these vocabularies.

The curriculum on the four PD&F goals also should repeatedly help each student understand how the student is building on earlier knowledge, skills, and capacities. A student’s growth on the four goals occurs in the context of the student’s preexisting stage of development on ownership over the student’s own continuous development (self-directed learning), responsibility and service orientation to others, and creative problem solving and good judgment. For example, many law students have substantial earlier experience with teamwork/collaboration or work requiring a service orientation. The curriculum – including mentoring and coaching – should focus on the intersection between the learner’s preexisting stage of development on these outcomes and the developmental stages the student must demonstrate to grow toward the level of competence of a practicing lawyer.

4.8 Principle 8 Think Very Differently about Assessment on PD&F Goals

Combine guided self-assessment with direct observation and multi-source feedback and assessment by faculty and staff.

Assessment to foster each student’s growth toward later stages of development on each of the four PD&F goals is going to be different from the straightforward reliance on written examinations or papers common in law school classes. Those methods have some place, but they are not geared principally to the task at hand. ABA accreditation standard 314 requires a law school to use both formativeFootnote 99 and summativeFootnote 100 assessment methods in its program of legal education to measure and improve student learning and provide meaningful feedback to students.Footnote 101 With those accreditation requirements in mind, we outline here practicable strategies for assessments on PD&F goals.

Lessons from competency-based medical education (CBME) are especially instructive here. The reader is advised to remember, however, that medical education has been in the business of purposeful support of professional identity formation for many years. Legal education is just embarking on its journey. We look here at assessment in medical education for illumination and its power of suggestion. It invites one to see how the assessment might be structured and conducted as legal education evolves in its support of PD&F goals.

In Chapter 3, we presented Table 12 that compared CBME to the traditional time-based (number of exposure hours) medical education that resembles traditional legal education. As Table 12 notes, assessment in a well-conceived competency-based educational model should include not just written exams and papers but also multiple assessment measures employing assessment tools that are “authentic” in the sense that they are or mimic actual professional work. Both formative and summative assessment will be needed. And the parties participating in the assessment process will be more numerous and varied. As explored in Chapter 2, both faculty and staff – in a “whole building” approach – are important observers of each student’s development with respect to the four PD&F goals. They thus can contribute to the assessment process.

To draw assessment of PD&F goals into clearer view, a key initial step is to look at the modules currently in the curriculum that foster student growth regarding any of the goals. Our Principle 1, you will recall, encourages the faculty and staff to envision progress along any PD&F goal as a process of stage development marked by the attainment of measurable Milestones. Principle 2 encourages faculty and staff to strive for curriculum and assessment modules that are coordinated and build on each other progressively. How does the current curriculum look? Does it present a linear progression of curriculum and assessment modules to foster student growth toward later stages of development of the particular goal? Are there gaps?

Another key initial step is to next ask in which modules faculty and staff will be able to actually observe each student and make informed judgments about the student’s stage of development on a particular goal. With that step done, you have identified significant opportunities for assessment.

Note that the assessment contemplated here is direct observation of students in authentic (real-life or mimicking real-life) professional experiences. In CBME, this kind of direct observation is mandatory for the reliable and valid assessment of PD&F competencies,Footnote 102 and we see no reason for disregarding that principle when considering PD&F goals in legal education. The direct observation contemplated here is considered a form of workplace-based assessment, with a student’s day-to-day work in an authentic professional experience observed and assessed. It is an assessment strategy that looks not only for what a student knows cognitively but also for whether a student “shows how” in a simulation or what a student “does” in a practice setting.Footnote 103

Multi-source feedback, widely used in CBME and also referred to as a “360-degree” assessment,Footnote 104 “is an assessment that is completed by multiple persons within a learner’s sphere of influence. Multi-rater assessments in CBME are ideally completed by other students, peers, nurses, faculty supervisors, patients, families and the residents themselves.”Footnote 105 Different respondents focus on the characteristics of the student or physician that they can assess; patients, for example, are not expected to assess clinical expertise.Footnote 106 High-quality assessment will use rating scales, evaluation forms, and the aggregation of multiple data points.Footnote 107 To provide reliability and validity, multiple assessors using multiple methods are required. Good observational assessment requires broad sampling across different encounters.Footnote 108 Together with rating scales and evaluation forms, narrative feedback also is very useful as feedback to the student.Footnote 109

A meta-analysis of the multi-source feedback process to assess physician performanceFootnote 110 emphasizes that multi-source feedback “has been shown to be a unique form of evaluation that provides more valuable information than any single feedback source. [Multi-source feedback] has gained widespread acceptance both for formative and summative assessment of professionals, and is seen as a trigger for reflecting on where changes in practice are required.”Footnote 111 In addition, “[Multi-source feedback] has been shown to enhance changes in clinical performance, communication skills, professionalism, teamwork, productivity, and building trusting relationships with patients.”Footnote 112 A second meta-analysis of multi-source feedback also concludes that it is reliable, valid, and feasible.Footnote 113

CBME assessment of observable behaviors also includes recording all instances of unprofessional conduct, for example, when a learner does not meet the requirements of the student conduct code or the profession’s code.Footnote 114 All University of Texas system medical schools, for instance, have developed some mechanism for identifying and recording student lapses in professionalism and engaging the student to reflect on the lapses.Footnote 115

How might the foregoing CBME assessment approach translate to legal education? Each law student might be required, for instance, to complete a regular self-assessment using a Milestone Model of the student’s stage of development on one or more of the four PD&F goals – especially after a significant authentic professional experience (in keeping with Principle 6). The student could be required to have good supporting evidence before selecting a stage of development. The burden might be placed on each student to seek out assessments, especially by direct observation by faculty and staff. Faculty and staff could use a relevant Milestone Model to assess the student’s stage of development. The law school’s curriculum and culture would encourage each student actively to seek experiences and assessments and feedback – and to reflect on the feedback to determine how to grow to the next level of development. Table 18 indicates opportunities for direct observations of students on the four PD&F goals that exist in the typical law school.

Table 18 Law school faculty and staff observing students on any of the four PD&F goals (especially in authentic professional experiences)

| All full-time and adjunct faculty supervising student projects that mimic real-life lawyer work like memos, presentations, briefs, and drafting legal documents, and including research assistant work |

| Experiential faculty like those teaching a clinic, lawyering skills, externships, simulations like negotiation, ADR, or trial advocacy |

| All staff assisting in the clinics or experiences |

| Supervisors of competitions like Moot Court, Negotiation, or ADR |

| Clients (in clinical settings) |

| Career services staff |

| Academic support and student services staff |

| Librarians working with students on projects |

| Student peers in work for credit or in student organizations on a competency like teamwork/collaboration |

| Mentor/coaches |

A long-term mentor/coach relationship is going to provide strong longitudinal observations and feedback. As discussed earlier in Principle 5, if each student meets regularly with a mentor/coach, the mentor/coach can facilitate guided reflection and guided self-assessment, including comparing the student’s self-assessment with the observations and assessments of faculty and staff. The coach then helps the student decide on the next action steps to grow to the next level on a competency. The coach can also provide an assessment using the relevant Milestone Model.

4.9 Principle 9 Student Portfolios Can Help Students Progress

Consider calling upon each student to create a personal portfolio on any one of the four PD&F goals, including an individualized learning plan to develop to the next level of growth.Footnote 116

Comparing traditional time-based (number of exposure hours) legal education with competency-based legal education, Table 12 in Chapter 3 makes clear that the “driving force for the process” in competency-based education for each student’s growth toward later stages of a goal shifts from the teacher to the student. Portfolios created and managed by the student help execute the shift. The student carries the burden to gather and demonstrate credible evidence that the student is growing to the next level on a competency. Portfolios are a very promising tool for empowering a student to be the driving force in the student’s development.

A portfolio is a “purposeful collection of student work that demonstrates the student’s efforts and progress in selected domains.”Footnote 117 In addition, “[p]ortfolios are recommended for capturing the combined assessments [for a student] and providing a longitudinal perspective.”Footnote 118 Drs. Holden, Buck, and Luk note that “[t]he aggregation of information into a portfolio would provide longitudinal perspective allowing for a broader view of students’ developmental trajectory not readily available from more narrow or discrete pieces of information.”Footnote 119 An E-Portfolio is simply a digital repository for the purposeful collection of the student’s work in one place. It enables each student, working with faculty and staff, to “create evidence of learning in creative ways that are not possible with typical paper-based methods. For example, E-Portfolios enable learners to demonstrate, reflect upon, and easily share scholarly and other work products using graphics, video, web links, and presentations.”Footnote 120

A medical education survey indicates the potential benefits of portfolios. By 2016, more than 45 percent of the medical schools in the United States were using student portfolios, with 72 percent of those using a longitudinal, competency-based portfolio strategy.Footnote 121 Eighty percent of students and 69 percent of faculty agreed that portfolios engage students. Ninety-seven percent of the faculty respondents agreed that there is room for improvement with respect to the use of portfolios.Footnote 122 A systemic review of all the empirical evidence on the education effects of using portfolios found that “the ‘higher quality’ studies identified by the authors suggest benefits to student reflection and self-awareness knowledge and understanding (including the integration of theory and practice) and preparedness for postgraduate training in which the keeping of a portfolio and engagement in reflective practice are increasingly important.”Footnote 123 To avoid student, faculty, and staff burnout, it is important to limit portfolios to no more than a few competencies that are the most important for the school.Footnote 124

An E-Portfolio curricular strategy applied by a law school to the student’s stages of development for teamwork or team leadership, for example, would require each student to collect evidence that demonstrates later-stage development of this competency. The student then selects the most credible and persuasive evidence that the student has achieved a particular stage of development. The student carries the burden to demonstrate that they are at a competent learner stage on teamwork or team leadership. The student therefore would need to contemplate what is the most persuasive evidence for audiences such as law faculty and staff, as well as audiences such as legal employers in the student’s areas of employment interest. The student then reflects on what the student needs to do to grow to the next stage of development regarding that competency and how to develop credible evidence of that growth. The student creates an individualized learning plan containing action items to grow to the next level, including authentic professional experiences and identification of the needed direct observations by faculty and staff.

Portfolios offer additional benefits than can merit noting. A portfolio approach to assessment

1. Provides a central location where all the observations from different stakeholders about a student’s performance regarding a competency are collected;

2. produces a collection of the student’s own on-going reflection into a longitudinal file;

3. assists mentoring and coaching, as the mentor/coach reviews a student’s portfolio on a given competency to provide feedback (and these mentor/coach observations, in turn, should be included in the portfolio); and

4. regularizes the student’s development of a written individualized learning plan that is revised regularly based on new experiences, feedback, and further reflection. The student is collecting the most persuasive evidence of later stage development on particular competencies.

4.10 Principle 10 Program Assessment on PD&F Goals Becomes Clear and Manageable if Principles 1 through 9 Are Heeded and Implemented

Progress on Principles 1 through 9, and particularly on Principles 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, and 9, will substantially support program assessment as required by ABA Accreditation Standard 315.

In time – exactly when will depend on how quickly law school and university accreditors move – a law school will be required to undertake program assessment on each institutional learning outcome that includes a PD&F goal to satisfy accreditation requirements.Footnote 125 A law school that puts Principles 1 through 9 into effective action – and particularly Principles 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, and 9 – will be creating a foundation for effective program assessment on any of the PD&F goals.

ABA Standard 315 currently requires “ongoing evaluation of the law school’s program of legal education, learning outcomes, and assessment methods” and provides that the faculty “shall use the results of this evaluation to determine degree of student attainment of competency in the learning outcomes and to make appropriate changes to improve the curriculum.”Footnote 126 ABA Interpretation 315–1 provides a number of examples of program evaluation methods including: review of the records the law school maintains to measure individual student achievement pursuant to Standard 314;Footnote 127 evaluation of student learning portfolios; student evaluation of the sufficiency of their education; student performance in capstone courses or other courses that appropriately assess a variety of skills and knowledge; bar exam passage rates; placement rates; surveys of attorneys, judges, and alumni; and assessment of student performance by judges, attorneys, or law professors from other schools.Footnote 128

For law schools that are within a university, the accreditation standards that the university must meet will differentiate between direct and indirect assessments and will require some direct assessment (also called direct measures) of student performance of a learning outcome competency. For example, the Council for Higher Education Accreditation now requires direct measures of student learning:

Evidence of student learning outcomes can take many forms, but should involve direct examination of student performance – either for individual students or a representative sample of students. Examples of the types of direct-measure evidence that might be used appropriately in accreditation settings include (but are not limited to):

– faculty-designed comprehensive capstone examinations and assignments;

– performance on licensing or other external examinations;

– professionally judged performances or demonstrations of abilities in context;

– portfolios of student work compiled over time; and

– samples of representative student work generated in response to typical course assignments.Footnote 129

A key point about program assessment for a law school to understand going forward is that the current ABA Standard 315 on program assessment is probably less demanding than the accreditation standards of the university of which the law school is a part. While ABA Standard 315 includes student evaluation of the sufficiency of their education (an indirect measure), the university standards will require at least one if not two direct measures on a PD&F goal in a law school’s institutional learning outcomes. It would be efficient to plan ultimately to meet the university’s standards.

A law school considering program assessment on any of the PD&F goals will benefit greatly from having a Milestone Model on the PD&F goal the school has incorporated in its learning outcomes, as contemplated by Principle 1. The law school can define the level of development that the school expects a target percentage of its students to achieve by graduation. Then the school can define the most practicable, least costly, and most efficient direct measure to assess whether the target percentage of students achieved that level of development. Implementation of Principle 2, which suggests a sequenced progression of modules in the curriculum for a PD&F goal, will provide a curriculum map of where best to assess student. Following Principles 4 and 5 will have each student writing guided reflections observed by a mentor/coach that can serve as direct measures of development on a PD&F goal. Principle 8 (on thinking differently about assessment) emphasizes the importance of direct observations of students performing a PD&F competency by faculty and staff including adjuncts, mentors, and coaches who observe student performance. These observers can assess each student’s stage of development using a Milestone Model. Principle 9 suggests consideration of portfolios, with the burden placed on each student to gather evidence demonstrating that the student has achieved the required level of development on a Milestone Model.

The development of practicable and efficient direct measures is an excellent area for cooperation among groups of law schools that have adopted any of the same PD&F goals.