Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Summary

Esotericists have, among many other things, conjured spirits, received messages from disincarnate beings, cast spells, interpreted horoscopes, and healed people by manipulating invisible “energies” that purportedly flow through the body. For at least some outside observers, this plethora of beliefs and practices is so outlandish that they have been led to wonder, in the words of sceptic Michael Shermer, why people believe “weird things.” The study of religions has developed a range of answers – cognitive, sociological, and historical – to the question of why people believe in the things they do. The issue of whether any of those beliefs are, to borrow Shermer's term, weird or irrational is another matter entirely.

Many people seem to find the purported irrationality of others to be a pressing issue: a vast literature exists in which entire fields of human activity are denounced as profoundly deluded. One fundamental problem with a sizeable part of that literature and its reactions to questions such as “is magic/channelling/astrology/healing irrational” is that the answers are often based upon little more than a subjective comparison between one's own cherished beliefs and those of others. It can, for instance, be deemed quite unremarkable to believe in the Trinity or the resurrection of Christ, while it is seen as irrational, weird, or even stupid to assume that the movements of the planets have anything to do with our character and destiny, or that reincarnation in a new body awaits us after death. For various reasons, not least in order to avoid the taint of being associated with this particular form of subjective mud-slinging, historians of religion have claimed that they either cannot or should not pass judgment on the behaviours and ideas of the people they study. This reluctance has deep historical roots: the founding father of the academic study of religion, Max Müller, defined the fledgling field as the value-free investigation of religious phenomena.

Besides using the words “rational” and “irrational” as subjectively wielded epithets, there are many cases where it seems appropriate to use the terms in some gut-level, pre-theoretical sense. If your long-term goal in life is to preserve your physical well-being, you will be more likely to achieve your goal by eating healthy food, refraining from smoking, and getting enough exercise than by casting spells against disease-bearing demons.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

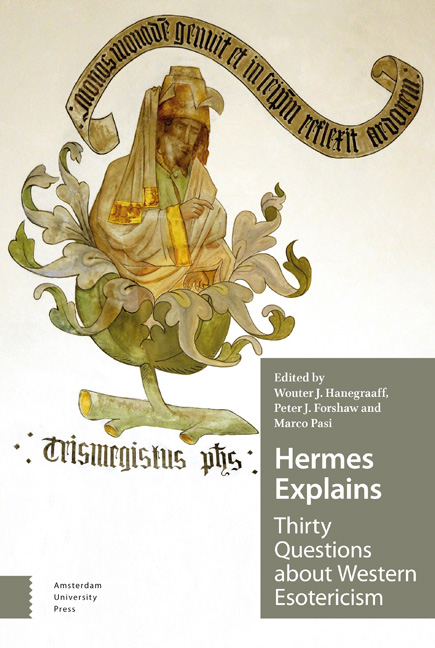

- Hermes ExplainsThirty Questions about Western Esotericism, pp. 137 - 144Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019