Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

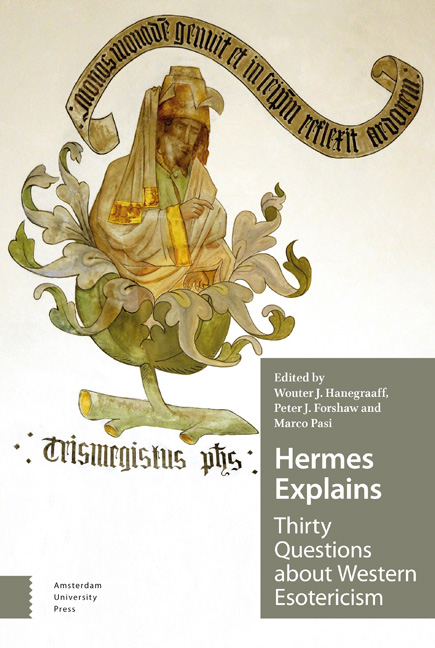

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Summary

Well, kind of, depending on how you define “spiritual” and the particular type of alchemy you’re talking about. The new historiography of alchemy prefers to speak of quite a wide variety of alchemies, rather than one generalised notion, and “spiritual alchemy” is a pretty contentious subject.

In the antique environs of third-century BCE Hellenistic Egypt, we first find a concern with decidedly material procedures: the imitation of pearls and the colouring of metals to look like gold, by means of a “spiritual” tincture, leading eventually to early attempts at Chrysopoeia (Gold-Making), the transmutation of base metals, like lead, into that most precious substance, gold. Greek traditions were adopted and transformed by the Persians and Arabs, from the eighth century CE, where we find the Sufi Jabir ibn Hayyan (fl. ca. 721-ca. 815), for example, promoting his Sulphur-Mercury theory of the composition of the Philosophers’ Stone and the idea of the production of an elixir capable of both curing human diseases and transforming lesser metals into gold. From the same period we have the earliest version (in Arabic) of what is arguably the most famous text of alchemy, the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, a short work that has been interpreted in a multitude of ways, as concerning gold-making, curing human sickness, personal transformation, and so on and so forth.

There is an undeniable interest in spirits in the work of the Persian polymath Rhazes (865-925) whose Kitab al-Asrar (Book of Secrets) explicitly discusses four “spirits,” but these are volatile substances, including Mercury, Sal ammoniac, Arsenic, Sulphur and have nothing to do with the “spiritual” development of the alchemist. However, a representative of alchemy as an inner science of spiritual transformation can be found in a work by the Andalusian scholar and mystic Ibn ʿArabi (1165-1240), a chapter of the Kitâb Al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya (Book of the Meccan Revelations), titled “On the knowledge of the alchemy of happiness and of its secret truths.” Ibn ʿArabi makes no claims to manual laboratory experience, but is aware of the theories of fellow Sufi Jabir and claims that alchemy is a science natural, spiritual and divine.

When alchemical texts first began to be translated from Arabic into Latin in twelfth-century Europe, the Christian West came to learn about Greek and Arab laboratory practice.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Hermes ExplainsThirty Questions about Western Esotericism, pp. 105 - 112Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019