Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Summary

In order for us to understand this question better, we must first ascertain the different streams within Kabbalah itself. While tradition contends that Kabbalah was first transmitted to Moses on Mount Sinai, Gershom Scholem (1897-1982), the father of the modern academic study of Jewish mysticism, based on historical evidence, describes Kabbalah as a phenomenon that emerges around the twelfth-thirteenth centuries in Europe as it was only until this late period that we see the doctrine of the sefirot take shape and people start referring to themselves as “kabbalists,” i.e. those who have “received” esoteric teachings.

Scholem identified three streams within Kabbalah. The first is the theosophical school sometimes referred to as Kabbalah iyunit or speculative Kabbalah where practitioners emphasise the study of text and theurgical operations. The second current is the meditative group sometimes credited as ecstatic or prophetic Kabbalah. This trend is championed by Abraham Abulafia (1239-ca.1291), the founder of ecstatic Kabbalah, who emphasised the use of shemot or divine names in his intense mind-altering meditations. The third category is the school of kabbalistic magic, also known as Kabbalah ma’asit or practical Kabbalah, where practitioners utilised objects, texts and incantations in order to produce magical effects. While these three classifications are by no means mutually exclusive, they serve as a useful frame of reference for scholars and researchers.

With regard to Jewish meditations, it would be tempting to simply revert to Abulafia – being a representative of the meditative school – and label all such activities as having an ecstatic dimension. After all, Abulafia’s techniques include not only yoga-like praxis such as postures, breath control, and body movements, but also written, pronounced and visualised letter permutation exercises which, if successful, are designed to induce ecstasy. Nevertheless, Abulafia and his followers did not have a monopoly on the practice of meditation. This is quite self-evident since, throughout the ages, meditative operations such as the daily Jewish prayers were practised by Jewish rabbis and kabbalists alike. In addition, Abulafia’s works were banned by the Jewish authority and thus their influence was quite limited.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

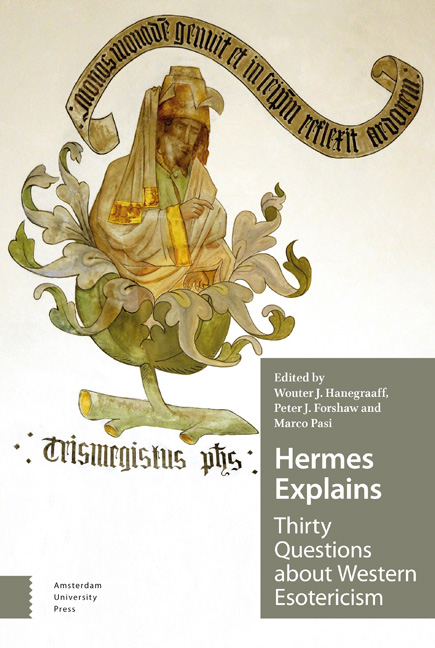

- Hermes ExplainsThirty Questions about Western Esotericism, pp. 184 - 190Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019