Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

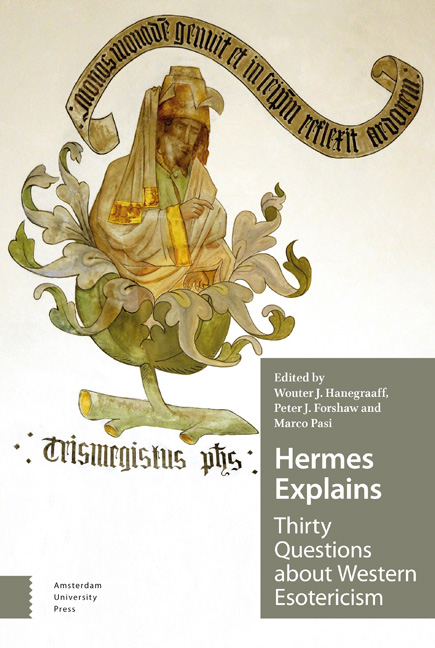

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Thirty red pills from Hermes Trismegistus

- Aren't we Living in a Disenchanted World?

- Esotericism, That's for White Folks, Right?

- Surely Modern Art is not Occult? It is Modern!

- Is it True that Secret Societies are Trying to Control the World?

- Numbers are Meant for Counting, Right?

- Wasn't Hermes a Prophet of Christianity who Lived Long Before Christ?

- Weren't Early Christians up Against a Gnostic Religion?

- The Imagination… You Mean Fantasy, Right?

- Weren't Medieval Monks Afraid of Demons?

- What does Popular Fiction have to do with the Occult?

- Isn't Alchemy a Spiritual Tradition?

- Music? What does that have to do with Esotericism?

- Why all that Satanist Stuff in Heavy Metal?

- Religion can't be a Joke, Right?

- Isn't Esotericism Irrational?

- Rejected Knowledge…: So you mean that Esotericists are the Losers of History?

- The Kind of Stuff Madonna Talks about – that's not Real Kabbala, is it?

- Shouldn't Evil Cults that Worship Satan be Illegal?

- Is Occultism a Product of Capitalism?

- Can Superhero Comics Really Transmit Esoteric Knowledge?

- Are Kabbalistic Meditations all about Ecstasy?

- Isn't India the Home of Spiritual Wisdom?

- If People Believe in Magic, isn't that just Because they aren't Educated?

- But what does Esotericism have to do with Sex?

- Is there such a Thing as Islamic Esotericism?

- Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?

- A Man who Never Died, Angels Falling from the Sky…: What is that Enoch Stuff all about?

- Is there any Room for Women in Jewish Kabbalah?

- Surely Born-again Christianity has Nothing to do with Occult Stuff like Alchemy?

- Bibliography

- Contributors to this Volume

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects

Summary

It may be easiest to begin with a common assumption: that being modern means being rational. The modern person has a scientific mindset, a pragmatic attitude, and trusts technology to solve our every problem. “Rationality,” in this common view, is the antithesis of being superstitious, believing in magic and spirits, or relying on quackery and pseudoscience. Rational moderns have left all that behind. Let's take a closer look at those assumptions.

That modern civilisation is a disenchanted one can seem intuitive. If we look at our major institutions, evidence of it is not hard to find. The guiding principles of economic life are efficiency, productivity, and profit. Healthcare and medicine are, for the most part, held to strict scientific standards of evidence. The legal system is built on a presumption of innocence according to which a prosecutor must make rational arguments based on evidence, credible testimony, and sound interpretation of law. In everyday life, we trust our engineers to create better smartphones, safer cars, and more efficient public transportation through advances in technology. Faced with global crises such as climate change, most of us now rely on the evidence of scientists and hope that new technologies can give us cleaner and more efficient sources of energy. In short, rational principles are key to how modern society is structured. There is little room for petitioning the spirits or consulting horoscopes to solve society's challenges.

No doubt: modern society is built primarily on science and technology rather than “magic,” broadly conceived. Nevertheless, something crucial is missing from this description: namely, the individuals who inhabit modern societies. Polls consistently show that a significant share of the population (usually around 40-50%) in putatively modern, post-industrial societies such as the United States or the United Kingdom, believe in “supernatural” phenomena such as ghosts and haunted houses, or “occult” powers such as telepathy and clairvoyance. In popular culture, filmmakers, TV scriptwriters, and authors of bestselling fiction cater to a huge audience hungry for storylines with occult themes – so much so that some speak of a “popular occulture” at the heart of modern society. Books that teach you how to attain success through positive thinking or “the law of attraction,” such as Rhonda Byrne's The Secret (2006), become international bestsellers. It seems that the modern attitude to enchantments is one of fascination rather than outright rejection.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Hermes ExplainsThirty Questions about Western Esotericism, pp. 13 - 20Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019