Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Chapter 5 - The Migrant Kings of Zululand

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 July 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

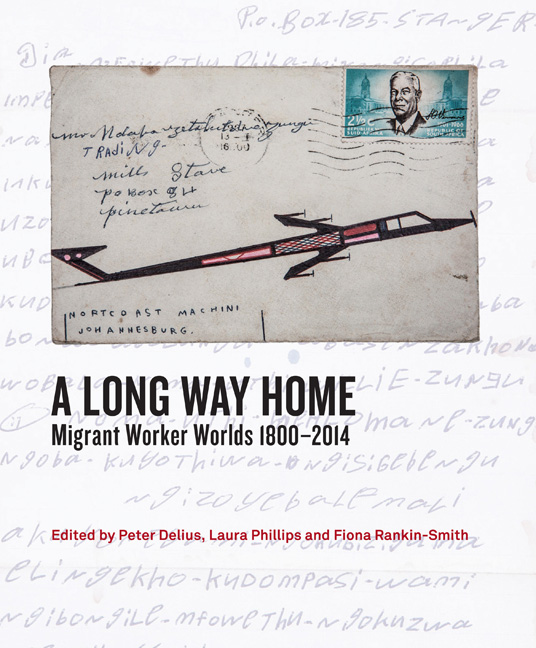

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Summary

The family of the old chief Matshana kaMondisa in Zululand quarrelled bitterly at the end of the nineteenth century. Their disagreements upset his amaSithole followers and his hallowed homestead, known as Sigedhleni. It once accommodated sacred war rituals of the umXhapho regiment, which annihilated the white enemy at the Battle of Isandlwana in January 1879. After the Anglo-Zulu War, Sigedhleni continued to serve as the amaSithole capital on the north side of the Thukela River in Nkandla division. By 1903, rumours were circulating that ‘ukuxabana noyise’, a ‘rift with father’ in the Mondisa lineage, had prompted a legal showdown. Such acrimony exposed the opportunities and perils of migrant labour in Zululand, a territory incorporated by the Natal Colony two decades after British troops finally defeated the Zulu kingdom in July 1879.

The contexts

The ‘rift with father’ stemmed from mutual antagonism between Matshana, a polygamist, and his son Ugudhla, the only boy born to Nomvimbi, an Indhlunkulu (Great hut) wife. She exercised influence in Sigedhleni by preparing her daughters to wed Zulu nobility, sealing alliances between her husband's lineage and this renowned dynasty of Africa. Nomvimbi also promoted the ambitions of her son, welcoming Ugudhla's wife and enlarging his herd with cattle bride-wealth, ilobolo, which she received for her nubile daughters. As a newlywed residing at home, Ugudhla wrangled with Matshana over property and the nuptial prospects of Nomvimbi's daughters. The younger contender felt entitled to decide family matters because his earnings from the Transvaal mines had saved his mother and her household from hardship. Ugudhla had acquired his wealth through South Africa's burgeoning capitalist order. His income symbolised a different route to traditional power, a path of mobility taken by young men who embraced opportunities afforded the ‘migrant kings’ of Zululand.

The outward movement of itinerant labourers disrupted domestic dynamics but it did not signal the collapse of homesteads. Since Iron Age settlement, the homestead represented a portable model of family reproduction and subsistence production, even after fratricidal successions in the Zulu kingdom spurred entire chieftaincies to relocate. Homesteads endured because they adapted to momentous change, particularly when foreign newcomers implemented heavy taxes and compulsory isibhalo (public work) demands. By the late nineteenth century, family patriarchs handled different political externalities, as well.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Long Way HomeMigrant Worker Worlds 1800–2014, pp. 74 - 88Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2014