Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures and tables

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter One What Moving Beyond Race Can Actually Mean: Towards a Joint Culture

- Chapter Two The Colour of Our Past and Present: The Evolution of Human Skin Pigmentation

- Chapter Three Races, Racialised Groups and Racial Identity: Perspectives from South Africa and the United States

- Chapter Four The Janus Face of the Past: Preserving and Resisting South African Path Dependence

- Chapter Five How Black is the Future of Green in South Africa's Urban Future?

- Chapter Six Inequality in Democratic South Africa

- Chapter Seven Interrogating the Concept and Dynamics of Race in Public Policy

- Chapter Eight Why I Am No Longer a Non-Racialist: Identity and Difference

- Chapter Nine Interrogating Transformation in South African Higher Education

- Chapter Ten The Black Interpreters and the Arch of History

- Notes

- Contributors

- Index

Foreword

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures and tables

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter One What Moving Beyond Race Can Actually Mean: Towards a Joint Culture

- Chapter Two The Colour of Our Past and Present: The Evolution of Human Skin Pigmentation

- Chapter Three Races, Racialised Groups and Racial Identity: Perspectives from South Africa and the United States

- Chapter Four The Janus Face of the Past: Preserving and Resisting South African Path Dependence

- Chapter Five How Black is the Future of Green in South Africa's Urban Future?

- Chapter Six Inequality in Democratic South Africa

- Chapter Seven Interrogating the Concept and Dynamics of Race in Public Policy

- Chapter Eight Why I Am No Longer a Non-Racialist: Identity and Difference

- Chapter Nine Interrogating Transformation in South African Higher Education

- Chapter Ten The Black Interpreters and the Arch of History

- Notes

- Contributors

- Index

Summary

In his novel about the English peasant revolt of 1381, A Dream of John Ball (1888), the great nineteenth-century artist and socialist William Morris makes this observation about the past in the present: ‘I pondered all these things, and how men fight and lose the battle, and the thing that they fought for comes about in spite of their defeat, and when it comes turns out not to be what they meant, and other men have to fight for what they meant under another name.’ Disclosed in this condensed reflection is an important lesson about how we think – or should think – in a properly historical way. Evidently, the relationship between the past and the present, between winning and losing (political struggles, for example), between what we aim for and what we get, is not what we would expect from the perspective of a seamless, linear notion of causes and results. Discontinuities are embodied in the appearance of continuities, and continuities are oft en characterised by surprising discontinuities. What Morris suggests is that history, how the past relates to the present, should be thought of as paradoxical. Notably too, his insight has about it a tragic aura, in that it solicits from us a suspension of our progressivist expectations about the secure connection between the intentions of reasoned agency and the outcomes of plurally constituted historical action. And therefore what is entailed in thinking historically is an ongoing attunement to the non-synchronicity of pasts in the present. I've found myself returning again and again to this singular recognition.

Indeed, although nowhere explicit, Morris's insight was constantly in the background of the thinking that went into my writing of Conscripts of Modernity. Part of the point of that book was to offer a historiographical intervention into the writing of present histories of the colonial past. Put it this way: a long struggle was waged against colonial domination that in some paradoxical fashion was both won and lost inasmuch as something new and important emerged into the world but at the price of preserving something old. CLR James's legendary book The Black Jacobins was of course my ostensible object (structured as it was around the themes of anti-colonial revolution and black political self-determination), and the contrast between romance and tragedy as modes of historical emplotment the specific theoretical axis of my preoccupations.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

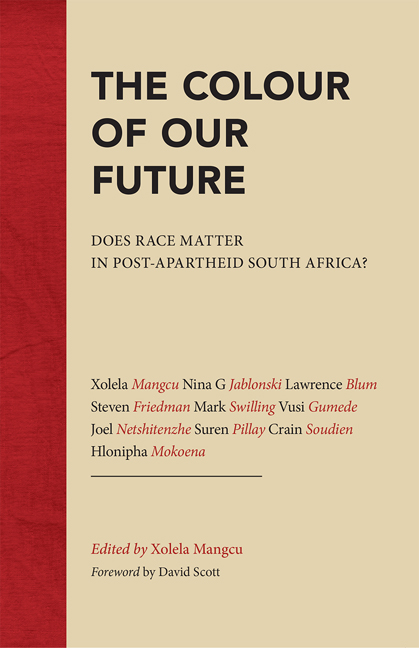

- The Colour of Our FutureDoes race matter in post-apartheid South Africa?, pp. ix - xiiPublisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2015