Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- 26 Bell Transistor

- 27 Oral Contraceptive Pill

- 28 Photocopier

- 29 Elstar Apple

- 30 Chanel 2.55

- 31 Lego Brick

- 32 Barbie Doll

- 33 Coca-Cola Bottle

- 34 Zapruder Film

- 35 Audiotape Cassette

- 36 Action Figure

- 37 RAM-Chip

- 38 Football

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

29 - Elstar Apple

from The Consumption Age

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- 26 Bell Transistor

- 27 Oral Contraceptive Pill

- 28 Photocopier

- 29 Elstar Apple

- 30 Chanel 2.55

- 31 Lego Brick

- 32 Barbie Doll

- 33 Coca-Cola Bottle

- 34 Zapruder Film

- 35 Audiotape Cassette

- 36 Action Figure

- 37 RAM-Chip

- 38 Football

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

Summary

AT THE FOOT of the Tian Shan mountains in central Asia, wild trees grow. By the end of each summer the trees are full of fruits, in colors that range from yellow to red, and in size from that of a marble to that of a tennis ball. Some are inedibly bitter and sour, but some are sweet and aromatic. Our ancestors’ preference for the sweet, large, and attractive specimens of the wild apple—Malus sieversi—led to the sorts of modern apples we now know and love. But when people first plucked apples from trees over 10,000 years ago, they surely gave little thought to the debates that would emerge of the intellectual property of apple species, and presumably never considered the way that millennia of breeding would be a vital aspect of food security in the 21st century. Yet, the way that we have domesticated apples and how we have chosen to protect apple varieties is deeply significant to our ability to feed humanity.

It would be difficult to reconstruct the birth of the modern apple, but the processes were likely very similar to the methods applied to other agricultural crops. Gatherers took the tastiest apples to their settlements and shared them with their communities to eat. Careless, they threw away the cores, allowing new trees to grow close to their home, where others could continue to pick them and continue the cycle. Generation after generation, our ancestors nurtured the trees bearing tasty and sweet apples, favoring those whose yields were high, and culling the poor producers. Over time this selection process led to a grouping of early domesticated apples.

From their home in central Asia, apples traveled the Silk Road to the West. Along the way, apple cores and seeds ended up beside the road, and the trees from this migration cross-bred with local, wild apple varieties. These crosses often happened with the European crabapple Malus sylvestris, leading eventually to our current species of apple, appropriately named Malus domestica. We know that medieval monks in Europe devoted themselves to the cultivation of tasty new apple varieties, and took as parent material the apples that grew in the neighborhood or those that they could readily exchange with other monasteries.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

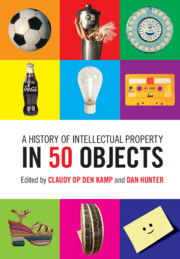

- A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects , pp. 240 - 247Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019