Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The regime of publicity

- 1 Public opinion from Burke to Byron

- 2 Wordsworth's audience problem

- 3 Keats and the review aesthetic

- 4 Shelley and the politics of political poetry

- 5 The art of printing and the law of libel

- 6 The right of private judgment

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- CAMBRIDGE STUDIES IN ROMANTICISM

- References

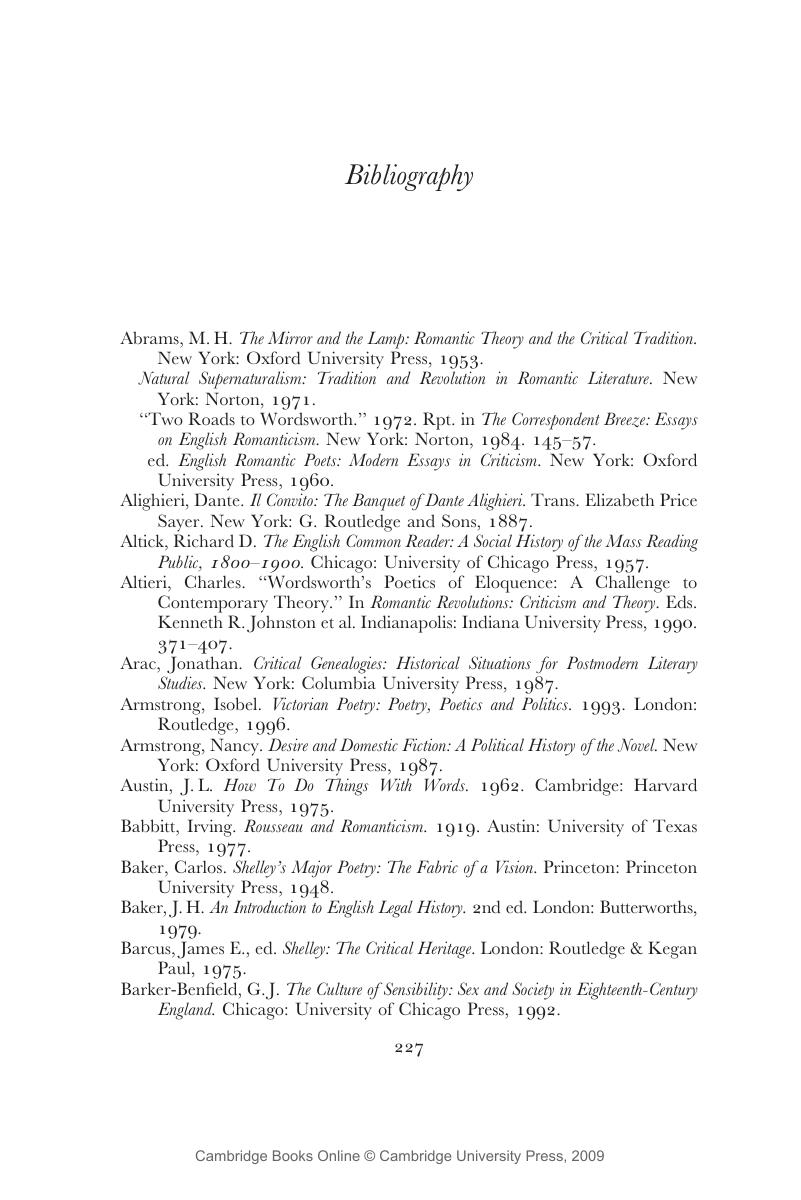

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 September 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The regime of publicity

- 1 Public opinion from Burke to Byron

- 2 Wordsworth's audience problem

- 3 Keats and the review aesthetic

- 4 Shelley and the politics of political poetry

- 5 The art of printing and the law of libel

- 6 The right of private judgment

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- CAMBRIDGE STUDIES IN ROMANTICISM

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Romanticism and the Rise of the Mass Public , pp. 227 - 240Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2007