Introduction

In the early 1830s, many Latin American countries had effectively integrated indigenous symbolism into their national iconography. The newly created Spanish American republics of Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru thus resuscitated old pre-Columbian myths and depicted legendary indigenous figures on their coins and official seals. Many creoles designated themselves Americanos, thereby indicating that they were fighting alongside mestizos, Indians, and Afro-Americans against a common enemy.Footnote 1 The most powerful form of Indianism arose in the empire of Brazil, where the romantic image of the ‘noble savage’ maintained its status as national allegory until the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 2

There is a scholarly consensus that this first phase of Indianism was inextricably bound to the creoles’ need to legitimize their struggle against Spain and Portugal. Through the evocation of a heroic pre-Columbian past, they wanted to underscore the differences between their American homelands and Europe. By creating a symbolic continuity between the ancient civilizations of the Aztecs, Incas, or Tupis, and the descendants of the conquistadors, the creoles sought to form a united front against their European enemy and strengthen their claim to self-governance. As many scholars have pointed out, this kind of Indianesque nationalism was merely symbolic, since the situation of the indigenous population did not change substantially in most Latin American countries after independence.Footnote 3 Thus, the early creole Indianism was no more than a strategic asset with no social consequences in the long term. With the exception of Brazil, the pre-Columbian past became integrated only as a distant heritage into national history, while the Indianist iconography was soon replaced by European symbols of freedom, order, and progress.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, the removal of Indianist symbols from the state’s emblems did not mean that the pre-Columbian past was completely forgotten. As María Elena Bedoya has shown for the cases of Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, the study of ‘antiquities’ remained an important activity among collectors and savants throughout the nineteenth century.Footnote 5

Following the demise of official Indianism, the political elite increasingly saw the indigenous legacy as an obstacle to progress and called for the gradual acculturation of natives by mestizaje or even by ‘whitening’ through immigration. Some held the opinion that these people had no relation to the remnants of ancient civilizations found in the Valley of Mexico, the Yucatán peninsula, or the Peruvian Andes. In fact, theories about the non-American origin of these civilizations became increasingly popular, indicating that such monuments were instead the result of long ago visits from Phoenicia, China, or even Atlantis.Footnote 6 Those who believed that contemporary indigenous groups were the descendants of once great civilizations generally claimed that three centuries of colonial rule and serfdom had led to the gradual degeneration of the ‘Indian race’.Footnote 7

After decades of downplaying the indigenous legacy, the study of pre-Columbian cultures experienced a remarkable renaissance in the last third of the nineteenth century, driven by the gradual professionalization of archaeology.Footnote 8 However, as Cristóbal Gnecco has noted, the new science also contributed to the alienation of native history by cutting the links between contemporary indigenous societies and the material references that expert knowledge began to classify as ‘archaeological registers’. On the one hand, this kind of epistemic violence lead to the negation of indigenous narratives, conferring on them a new and decontextualized meaning.Footnote 9 On the other hand, those narratives were also appropriated in order to serve as metonymic building blocks for national histories constructed over a dichotomy that celebrated the native societies of the past but condemned the indigenous cultures of the present.Footnote 10

Among the most important spaces to showcase the new dedication to the pre-Columbian past and the contemporary indigenous groups were the great world’s fairs – the nineteenth century’s most important mass gathering events, staged to celebrate civilization and progress on a global scale. Although the fairs were usually designed by the political, cultural, and economic elite of the host country, they nevertheless attracted huge crowds of visitors from every stratum of society. Thus, according to Jürgen Osterhammel, no other contemporary medium comprised the universalistic claim of the Atlantic West in a better way than the large fairs held in Europe and the United States before the turn of the century.Footnote 11

As early as 1851, when the first of these exhibitions was held at the Crystal Palace in London, they were perceived by Latin American elites as an opportunity to define how a truly modern nation could and should look. In this respect, they used the fairs to promote the modernization process within their own countries. However, since the Latin American economic model was based on the exportation of primary goods, the region’s pavilions at the world’s fairs contained mainly raw materials and some simple manufactured products. In addition, they were considered promotional platforms to attract immigrants and capital. From the first Latin American fair participations in the 1850s, there was also a strong focus on pre-Columbian objects, as well as ethnographic exhibits. By the end of the nineteenth century, Brazil, Mexico, and Peru had already participated in several important world’s fairs, exhibiting a great array of items related to indigenous cultures.Footnote 12

What remains neglected in historiography, however, is the equally relevant scientific context of these mass gatherings. Unlike the romantic Indianism celebrated at earlier fairs, the archaeological and anthropological exhibits at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889 and the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 – with roughly 28 million visitors each – were designed according to the latest scientific findings. Thus, the strong focus on archaeological and anthropological displays within the Latin American pavilions was not just a means to integrate the indigenous past into national history but also reflected the desire of local elites to participate in modern scientific discourses.

The world’s fairs were platforms for establishing a dialogue between Latin American researchers, intellectuals, amateur historians, and collectors, and their North American and European counterparts. Although archaeology and anthropology were not yet institutionalized in most Latin American countries, the delegates at the fairs communicated extensively with scientists from the US, Britain, France, and Germany, many of whom had travelled to Latin America in search of ‘antiquities’.Footnote 13 Since the great exhibitions of Paris and Chicago hosted a huge number of scientific congresses on matters such as anthropology, archaeology, public works, the arts, religion, and medicine, many Latin American intellectuals were eager to be involved. Participation promised not just prestige but also the exchange of ideas with some of the most renowned scientists of the day.

As these congresses and displays had a major impact on the formation of science in both America and Europe, the fairs themselves can be understood as ‘spaces of global knowledge’, as defined by Diarmid Finnegan and Jonathan Wright. According to these authors, ‘global knowledge’ refers to a form of knowledge that ‘moves between and beyond multiple and widely dispersed territories or locales and connects individuals or institutions distributed across the world’. However, as they point out, for the purpose of historical research it could be equally useful to take the ‘mental dimension’ of knowledge circulation into account. For that reason, they draw our attention to the historical protagonists’ own perception of the ‘global’, as well as to certain regulative ideals behind nineteenth-century knowledge production, and they are less concerned with the ‘actual’ level of worldwide interconnectedness.Footnote 14

We should nevertheless avoid thinking of the world’s fairs as ‘neutral’ platforms of knowledge exchange, since colonial and imperial ideologies were pervasive at these events. On the one hand, they constituted peaceful spaces for negotiation and transculturation that transcended the boundaries of the nation-state. On the other, these ‘contact zones’ were characterized by highly asymmetric power relations between the supposedly civilized host countries and the periphery participants, at both the epistemic and the material level.Footnote 15

In what follows, I will first outline Latin America’s participation in the most important world’s fairs of the nineteenth century, focusing on the Brazilian, Mexican, and Peruvian displays of 1889 (Paris) and 1893 (Chicago). This selection is based on the importance that these countries accorded to archaeological and anthropological exhibits, as well as the unprecedented importance of scientific conferences at the late nineteenth-century fairs. I will not, however, consider the even larger Paris Universal Exposition of 1900, since Brazil did not participate and Mexico avoided any display of pre-Columbian cultures.Footnote 16 After this short account, I will analyse in detail how the visualizations and displays of indigenous cultures at the fairgrounds were entangled with scientific discourses, presenting the cases of Brazil, Mexico, and Peru in order of their size and relevance.

Latin America at the nineteenth-century world’s fairs

As I have mentioned above, the Latin American elite showed interest in the world’s fairs as early as 1851. However, participation in the exhibitions of London and Paris in the 1850s was of a rather exploratory nature. Since Latin American countries such as Mexico and Peru, which participated officially at the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1855, lagged far behind their European ‘mentors’ in terms of technological development, infrastructure, education, and science, the focus of their small exhibits was on raw materials such as hides, wood, and minerals, as well as some artwork.Footnote 17 As Natalia Majluf has pointed out, archaeological or ethnographic reconstructions were still uncommon features of the early world’s fairs, and the Latin American countries were confined to the industrial and fine art sections.Footnote 18 Although Peru presented some paintings with pre-Columbian themes at the 1855 exhibition, the response was rather negative. Apparently, the essentially European audience had expected something more ‘exotic’. Since the deployed artistic techniques derived from French or Italian art academies, where nineteenth-century Latin American painters frequently received their training, the Peruvian representation of Andean culture and nature was roundly condemned for its supposed lack of authenticity. According to Majluf, Peru’s and Mexico’s failure to accommodate European expectations drove the Latin American exhibition organizers to place emphasis on archaeological and ethnographic sections in later fairs, thus ‘defining the national through the presentation of natural and archaeological specimens as metonymic fragments of the nation’.Footnote 19

As a result of this experience, from the 1860s onwards Brazil, Mexico, and Peru focused heavily on exhibits that they anticipated would generate public interest and approval. In the case of Brazil, which entered the arena of the world’s fairs in 1862, huge Indianist displays and ethnographic sections became the defining feature of its fair participation during the empire (1822–89) and afterwards. In many cases, those displays were a direct response to the European hosts, as in 1867, when the organizers of the Paris Universal Exposition requested that Brazil display ‘images and costumes of the locals’, especially its ‘Indians, peasants and gauchos’.Footnote 20 At the same fair, Mexico would steal the show with a life-size pre-Columbian ‘temple’, modelled after the pyramid of Xochicalco.Footnote 21 Peru participated only belatedly in some of the nineteenth century’s most important exhibitions, such as the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 and the Paris Universal Exposition of 1878. Its acclaimed pavilion, adorned with pre-Hispanic elements, marked the beginning of the so-called ‘neo-Peruvian’ architectural style, which would become widespread at the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 22

From the Great London Exhibition of 1862 onwards, Latin American national displays became a common sight at the world’s fairs in Europe and the US, with Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina being the region’s most regular participants. They were joined sporadically by Chile, Colombia, Venezuela, Paraguay, Bolivia, and the Central American republics at the fairs of Paris (1867, 1878, 1889, 1900), Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876), and Chicago (1893), as well as at some minor international, national, and regional exhibitions. Because the enthusiasm for staging gigantic fairs in Europe and the US – and on a smaller scale in Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Australia – began to die down after the turn of the century, the period between 1851 and 1900 is often labelled as the ‘age of exhibitions’.Footnote 23

Although the presentation of archaeological and ethnographic objects was a common feature of the world’s fairs from the 1860s onwards, such displays became much more nuanced and science-based during the last third of the nineteenth century, especially at the fairs of 1889 and 1893. Thus, as Mauricio Tenorio Trillo has remarked, to understand the sociopolitical function of these exhibits one has to take the scientific debates ‘behind the scenes’ into account.Footnote 24 What was initiated in the 1850s to please the exoticism of European visitors to the fairs had become a matter of national pride and proof of ‘scientific modernity’ by the end of the century. Consequently, the regime of Porfirio Díaz in Mexico, the imperial as well as the republican rulers of Brazil, and the constitutionalist governments of Peru all used the fairs of the 1880s and ’90s to (re-)construct their version of a ‘Latin American antiquity’ according to the scientific standards of the day. From this perspective, the modern nation-state could be thought of as the culmination of thousands of years of ‘American’ history, thereby rebuking negative European conceptions of the ‘New World’ – a ‘continent without history’ – in the words of Hegel.Footnote 25

Although the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889 was held to celebrate the centenary of the French Revolution, archaeological and anthropological displays were a prominent feature, as several national pavilions and especially the popular habitation humaine exhibition – a display of dwelling houses from all over the world – demonstrated. However, despite the many spectacles, such as ‘human zoos’, giant dioramas, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, or the orientalist ‘Street in Cairo’, the 1889 world’s fair is primarily remembered because of the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the nineteenth century’s most impressive symbol of modernity, combining architectural elegance with raw functionality.Footnote 26 Moreover, the city of Paris was ‘Latin America’s secret capital’, the presumed ‘centre of civilization’, where a large Latin American community had developed and where the very concept of ‘Latin America’ was forged in the 1850s.Footnote 27 It is thus hardly astonishing that all the Latin American countries attended the Paris fair, though not necessarily with a national pavilion.

At the end of the 1889 exhibition, the United States announced its intention of organizing the next world’s fair, this time with the explicit purpose of celebrating the discovery of America 400 years previously. Thus, in the context of the quadricentenary of Columbus’ discovery, it is no wonder that Latin America’s presence at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago was almost as visible as it had been in Paris. This time, however, just eight of the region’s eleven nations that joined the fair were represented through their own pavilion. In the cases of Mexico and Peru, financial problems were responsible for the comparatively small exhibits and the lack of national pavilions, while Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Chile abstained from attending the fair because of political turmoil.Footnote 28 In general terms, the Chicago fair was characterized by tension between Hispanism and Pan-Americanism. Whereas the adherents of Hispanism on both sides of the Atlantic sought to tighten the cultural and political bonds between Spain and her former colonies, the US proponents of Pan-Americanism were primarily interested in economic expansion towards the southern ‘sister republics’.Footnote 29 In both cases, the declared aims of cultural exchange and political equality could hardly veil the imperialist interests and paternalist attitudes behind such rhetoric. One North American guidebook for the Chicago fair even described the Latin American countries that attended as ‘our foster children’.Footnote 30

Since the official reason for the staging of the Chicago fair was the celebration of the quadricentenary, archaeology and anthropology were even more important than they had been four years previously in Paris. The most impressive demonstration of how advanced North American scientific institutions were in these emerging fields of knowledge was the huge Department M, whose official title was ‘Anthropology: man and his works’.Footnote 31 Directed and organized by the Harvard professor Frederic Putnam and his chief assistant, Franz Boas, this building contained an archaeological and anthropological display that ‘no previous Exposition has approached … in the completeness and instructive interest’.Footnote 32 Since many Latin American displays in Department M were actually obtained and categorized by North American exhibition specialists, the whole department could also be seen as a manifestation of epistemic imperialism, through which North American institutions tried to merge, and ultimately dominate, the pre-Columbian past by replacing it with the more inclusive concept of ‘American prehistory’ in the context of a growing informal imperialism in Latin America.Footnote 33

Despite the imposing size of the anthropology building (415 by 225 feet), the space allotted to foreign exhibitors was much smaller than in Paris. Furthermore, foreign as well as national exhibitors were obliged to arrange their ethnological materials by tribes and their archaeological exhibits by localities. Only ‘in three or four instances’ were the owners of large mixed collections able to maintain the original unity of their loans. In general terms – and in contrast to the Parisian habitation humaine exhibition – Putnam’s organizational scheme was so rigid that only Brazil, Costa Rica, and Mexico opted for official government-sponsored exhibits in Department M.Footnote 34 The remaining Latin American countries preferred to exhibit their pre-Columbian objects inside their national pavilions instead. In addition, as Alejandra Uslenghi has pointed out, the US government-sponsored Bureau of the American Republics partly assumed the representation of the Central and South American republics at the Chicago fair, thus further restricting the possibilities for autonomous national self-representation.Footnote 35

Envisioning an Indianist empire

Despite an increasingly difficult political situation at home, no Latin American country allocated more resources to the world’s fairs of 1889 and 1893 than Brazil. After the abolition of slavery in May 1888, the already strong republican opposition to Dom Pedro II’s long-lasting empire became even more vigorous, as important conservative groups of ex-slaveholders withdrew their support from a government that many felt to be completely out of touch.Footnote 36 In this context, it is no wonder that Pedro was reluctant to officially attend the Paris Universal Exposition, held to celebrate the overthrow of the French monarchy in 1789. In the end, as a compromise, the private French–Brazilian Syndicate was commissioned to organize the national display in Paris, while the imperial government acted as an informal sponsor.Footnote 37 However, the antimonarchical undertone of the Paris fair proved to be premonitory for events in Brazil, since Pedro’s government was toppled by a military coup just two weeks after the end of the exhibition, on 15 November 1889. Notwithstanding the conditions in the wake of the coup, a virtual civil war that gave birth to a republican federal system, the new elites – mainly army officers – decided to attend the Chicago fair in order to celebrate the ‘new Brazil’ before an international audience.Footnote 38 Inspired by Comtean positivism and eager to showcase the country’s advancements in the fields of machinery, electricity, and military technology, they relegated the display of pre-Columbian artefacts to second place in Chicago. Nevertheless, on both occasions Brazil’s imposing neo-classical pavilion featured huge Indian figures on its façade, which were meant to be ‘allegorical and representative’ of the country.Footnote 39

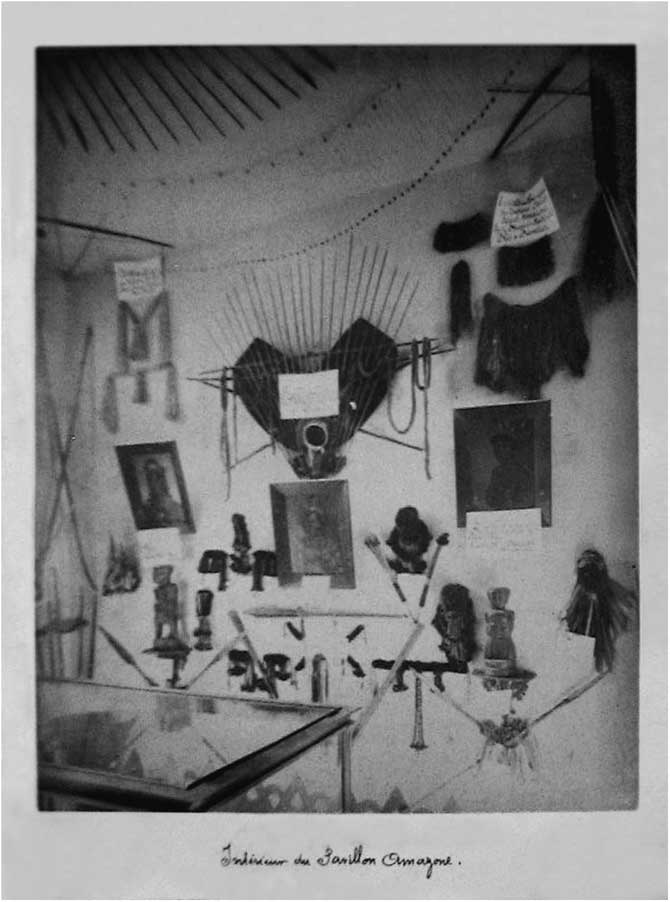

Although Brazil was not specifically famous for its pre-Columbian civilizations, the institutionalization of archaeology and anthropology occurred much earlier in that country than in Spanish America.Footnote 40 Thus, the interest of the Brazilian elite in studying the remote past was in great part motivated by the desire to create a foundational ‘antiquity’, which also coincided with the official cultivation of Indianism, the most powerful national allegory during the empire.Footnote 41 One crucial factor for Brazil’s success at the world’s fairs from 1862 onwards was the parallel evolution and professionalization of a series of cultural and economic institutions, supporting the exhibition planners’ efforts in many ways.Footnote 42 One of the most relevant of these institutions was the Rio de Janeiro-based National Museum. Under the leadership of the botanist and ethnologist Ladislau Netto, who had taken over as director of the museum in 1876, the institution became one of the most advanced places for the study of natural history, ethnology, and anthropology in South America. Netto also participated actively in global scientific debates, wrote several articles for European academic journals, and was a much-respected member of the scientific community of his time.Footnote 43 The museum’s display in Paris consisted of various ceramics from the Amazonian island of Marajó, as well as bones, weapons, jewellery, and crafts which had been made by supposedly ‘civilized’ Indians (Figure 1).Footnote 44

Figure 1 ‘Interieur du Pavillon Amazone’ (albumen print, 21×17 cm, 1889). Source: Arquivo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro.

In fact, as Netto’s participation in the 1889 Congress on Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology in Paris shows, the study of the Marajó culture formed the backbone of his endeavour to construct a Brazilian antiquity. Accompanied by the German zoologist and physician Hermann von Ihering, the physician and anthropologist João Batista de Lacerda, the anthropologist José Rodrigues Peixoto, and the writer José Veríssimo de Matto, Netto delivered several speeches on Brazil’s ‘ancient foundations’, stating that the ancient inhabitants of Marajó had probably arrived from the Mesoamerican cultural area. According to him and to Veríssimo, who was actually born in the Amazonian province of Pará, this could be deduced from the very similar jade artefacts found in the two regions.Footnote 45

Although Brazil wanted to be perceived as part of the ‘civilized’ world, and took pride in its monumental pavilion beside the Eiffel Tower, its technical equipment and machinery, and the visualization of its ‘Europeanized’ population in the photographic gallery, it was Netto’s ethnographic exhibition that attracted the most attention in 1889.Footnote 46 In his double function as display designer and congress attendee, Netto downplayed the relevance of contemporary indigenous cultures in Brazil, focusing instead on the ‘prehistoric Indian’. Together with some newly acquired exhibits, all Brazilian ethnographic objects were displayed in the peculiar ‘Inca dwelling’, which was part of the comprehensive habitation humaine exhibition.

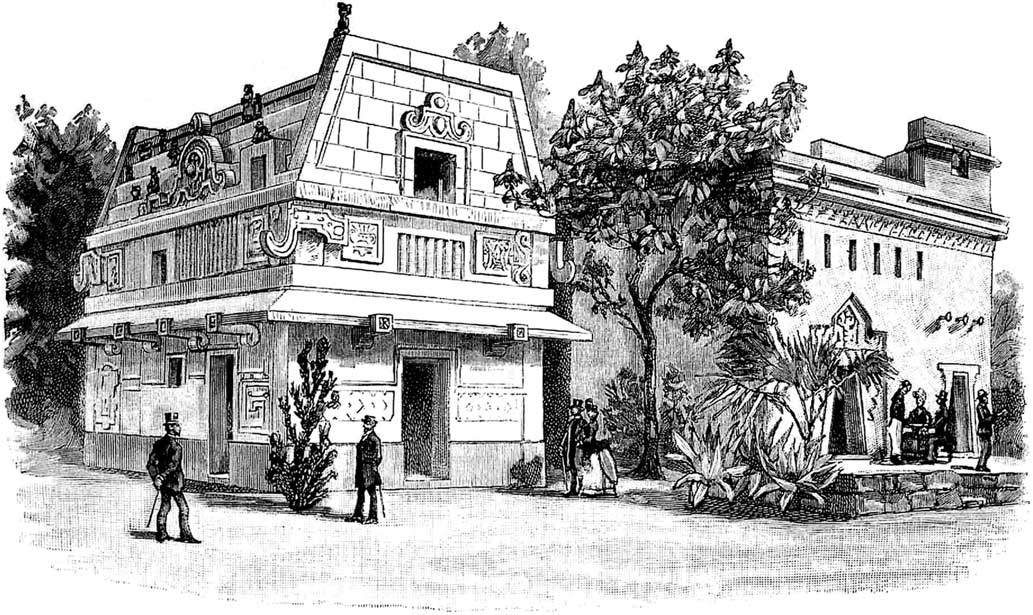

This so-called Casa Inca (Figure 2) was the brainchild of Charles Garnier, the famous architect of the Paris Opera and the man responsible for the general layout of the habitation humaine.Footnote 47 In fact, the building resembled a European house and was only vaguely modelled after archaeological findings in Peru and Bolivia, though the decorative work was inspired by original pre-Columbian artwork. However, these buildings were not solely the products of Garnier’s inventiveness, since when designing the habitation humaine he worked closely with the Mexican, Peruvian, Ecuadorian, and Brazilian commissioners, who sought to visualize the existence of a ‘Latin American antiquity’ by emphasizing the supposed progressiveness of America’s original inhabitants. As a result of his negotiation with the Latin American exhibition planners, Garnier wanted to create the impression that the Incas and Aztecs had possessed ‘dwelling houses’ similar to those in Europe.Footnote 48 However, his creations aroused some controversy. One highly critical journalist even accused him of fabricating mere ‘inventions’, or ‘childish toys without any scientific use’.Footnote 49

Figure 2 ‘Palacio de los Aztecas y de los Incas’. Source: F. G. Dumas and L. de Fourcard, eds., Revista de la Exposición Universal de París en 1889, Barcelona: Montaner y Simón, 1889, p. 104.

It is not entirely clear from the available sources why the National Museum’s indigenous weapons, ceramics, and artefacts ended up in the Casa Inca, which the Brazilians baptized the ‘Amazonian Palace’.Footnote 50 Indeed, the objects from Marajó and other archaeological sites were displayed beside Inca and Aztec artefacts – that is, completely separated from their original historical and geographical context. Yet Netto was very pleased with Garnier’s spatial layout for the habitation humaine, the logic of which followed contemporary theories on ‘human development’ by assuming evolutionary stages from ‘prehistoric’, through ‘historic’, and finally to ‘isolated civilizations’. Brazil’s indigenous cultures on display could thus be classified as both ‘prehistoric’ and ‘isolated’.Footnote 51 Consequently, both Brazil and Mexico avoided any reference to the ongoing persecution and forced assimilation of contemporary indigenous groups within their national territories.

Although the regime change of 1889 brought about a purge of most public institutions, Netto remained in charge of the National Museum. Despite the continuity of this and other imperial institutions, the new republican government sought to put greater emphasis on technological exhibits and raw materials than on the pre-Columbian past. In this context, and maybe because of the much more restricted conditions imposed by Putnam’s organizational scheme in Department M, the anthropological display at the World’s Columbian Exposition turned out to be much smaller. Thus, in contrast to the Parisian Congress on Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology, which counted several Brazilian delegates, not a single one appeared at the subsequent congress in 1893. Clearly, the republican government’s preferences had shifted. As José Murilo de Carvalho has shown, the years after the downfall of the empire also marked the beginning of the search for a new republican national imagery, ultimately abandoning traditional Indianism.Footnote 52

Nevertheless, as the politician and amateur historian José Coelho da Gama e Abreu, the Baron of Marajó, wrote in a Chicago newspaper’s special edition on Brazil at the world’s fair, the anthropological exhibit in Department M was still very impressive. Indeed, in his view it exceeded that of other countries ‘in the beauty and number or in the magnitude of objects’.Footnote 53 Most interestingly, however, the objects from different burial mounds of the Marajó island once again evoked a glorious Brazilian antiquity. Thus, Abreu compared the findings to Greek and Egyptian artefacts, and even mentioned the ‘incapacity and ignorance’ of present-day Indians.Footnote 54 The construction of the Marajó culture as a ‘highly developed ancient civilization’, and its almost clinical separation from the ‘decadent’ Indians of the present, was apparently inspired by the academic discussions between Ladislau Netto and his international peers at the Paris fair.Footnote 55

Besides the display of the Marajó culture, which was again organized by Netto, there were numerous artefacts from other states on display. Most of them were taken from the National Museum’s collection, but some were privately owned and leased for exhibition.Footnote 56 Far more spectacular than this rather modest display was the presentation of ‘live Indians’ in the Brazilian concert hall. Although constructed to present ‘high culture’ to the international audience, including plays by the famed composer Carlos Gomes, the building also featured ‘dances performed by the natives from the interior of Brazil’, in order to meet the exhibition visitors’ demand for exoticism.Footnote 57 In fact, together with the display of a 41-ton pyramid of pure gold in Brazil’s national pavilion, the ‘dancing Indians’ were among the exhibits that attracted particular attention from international journalists.Footnote 58

In conclusion, the imperial government was quite successful at envisioning a ‘Brazilian antiquity’ at the Paris Universal Exposition, as the many positive comments in the international press show. Though the Marajó culture was not comparable to those of the Aztecs and Incas, which were generally considered more advanced, the Brazilian exhibition planners managed to elevate the Marajó culture to a similar ‘level of civilization’, while Brazilian intellectuals and scientists participated actively in debates over possible cultural connections between Mesoamerica and northern Brazil. At the Chicago fair, however, Brazil focused much more on technical equipment, raw materials, and exoticism. Possibly because of the republican government’s new political iconography and the anthropology department’s more rigid organizational scheme, the display of a ‘glorious indigenous past’ was relegated to second place.

‘Souvenirs de la patrie mexicaine’

Maintaining the ‘right balance’ between displays of material progress and those of exoticism was also a challenge for Mexico, the second most important fair participant from Latin America. Although in Mexico the institutionalization of archaeology occurred later than in Brazil, beginning with the re-establishment of the National Museum in 1865, the authoritarian regime of Porfirio Díaz, the so-called Porfiriato (1876–1911), invested heavily in the study of history, archaeology, and anthropology from the 1880s onwards.Footnote 59 Accordingly, in 1885 the Bureau of Inspection and Conservation was founded under the guidance of the archaeologist Leopoldo Bartres, and in 1887 the National Museum created a special section for archaeology.Footnote 60

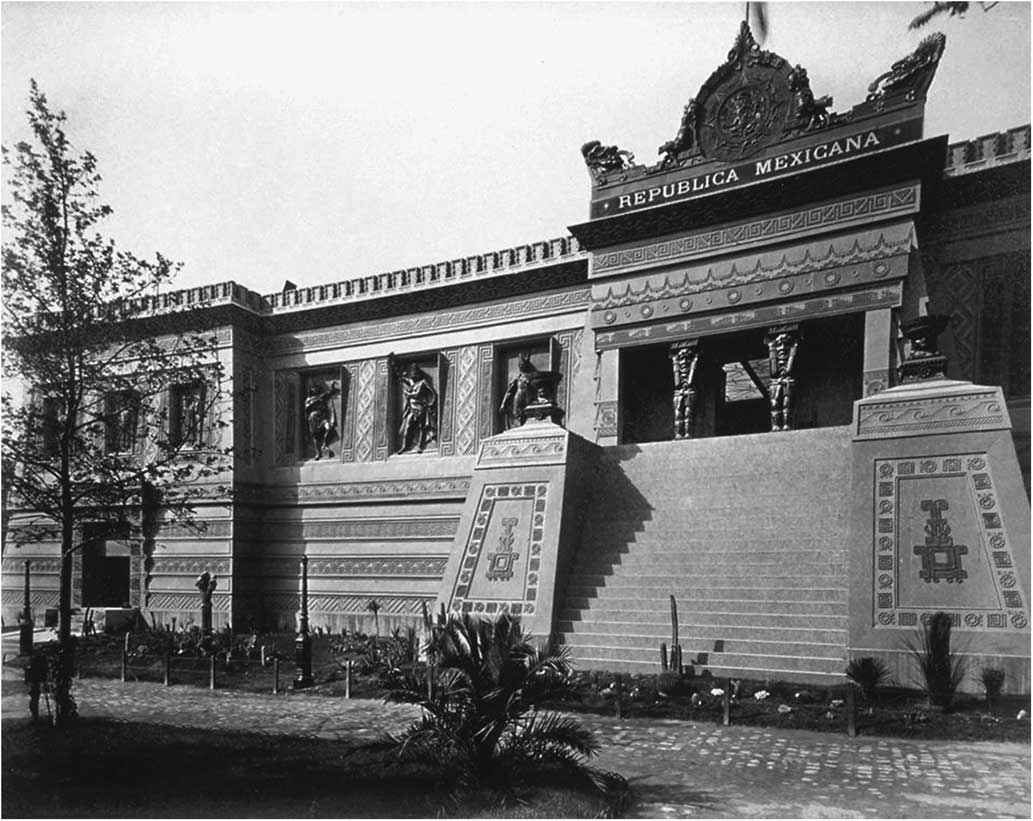

This gave rise to a new wave of Indianism, reflected in neo-Aztec motifs in architecture, the construction of a monument to the last Aztec emperor, Cuhautémoc, on Mexico City’s Parisian-style Reforma boulevard, and the restoration of the pyramids of Teotihuacán under the direction of Bartres.Footnote 61 Nevertheless, one of the most memorable Indianist projects of the Porfiriato was the giant neo-Aztec pavilion at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889, which has been analysed in depth by Mauricio Tenorio Trillo.Footnote 62 According to this scholar, the pavilion should be seen as the product of prolonged discussions about the appropriate national image of Mexico and the search for an authentic architectural style, combining pre-Hispanic and neo-classical elements in an original manner. The so-called Aztec Palace, designed by the historian, statistician, and archaeologist Antonio Peñafiel and executed by the engineer Antonio Anza, thus contained Greco-Roman elements as well as allegorical representations of pre-Columbian deities.Footnote 63

In a manner similar to his Brazilian counterpart, Ladislau Netto, Peñafiel also participated actively in global intellectual networks and was the decisive figure in organizing Mexico’s pre-Columbian displays in Paris and Chicago. He attended the Paris fair personally and delivered a speech on ‘Mexican archaeology’ at the 1890 Congress of Americanists, which took place a few months after the end of the exhibition.Footnote 64 Though he was by no means a professional archaeologist, he published widely in the fields of history and archaeology; he made his living as a physician, as a politician, and finally as director of the National Institute of Statistics, conducting the first nationwide census, in 1895. His best-known publication is the three-volume, government-sponsored Monumentos del arte mexicano antiguo (1890), which contains a great number of high-quality lithographs and photographs, as well as an introductory section written in Spanish, French, and English.Footnote 65 In Paris, Peñafiel presented the publication personally to the congress participants, explaining that this endeavour was only in part driven by scientific interest. The purpose of the album was not just to give an overview of Mexico’s ancient cultures – especially the Aztecs – but also to highlight the use of pre-Columbian elements in Mexican art and contemporary architecture. The book contained a selection of picturesque ‘souvenirs de la patrie mexicaine’, which he considered to have an aesthetic worth equal to artistic elements of Greek and Egyptian origin, and which inspired his design of the Mexican pavilion in Paris (Figure 3).Footnote 66 According to one journalist, the Aztec Palace was indeed the only Spanish American pavilion worthy of recommendation, since it was of ‘frankly indigenous character’.Footnote 67

Figure 3 ‘Pavilion of Mexico, Paris Exposition, 1889’ (albumen print). Source: Library of Congress, prints and photographs division, Washington, DC.

However, Peñafiel’s design was a far cry from the ‘purest Aztec style’, as he claimed in an informative brochure distributed at the fairgrounds.Footnote 68 In fact, several of the depicted deities, symbols, glyphs, and sculptures belonged to other cultures, such as the Toltecs, the Mixtecs, the Zapotecs, and the Mayas. Nevertheless, in this pamphlet, which explained in detail the meaning and origin of each of the decorative elements on the façade, Peñafiel demonstrated great knowledge of the different pre-Columbian cultures, drawing mainly on the early chroniclers of the conquest, such as Diego Durán and Bernal Díaz del Castillo. In addition, he mentioned some ‘eminent antiquarians’, as well as contemporary historians, as his sources of inspiration.Footnote 69 However – and this is probably the most astonishing feature of this short text – Peñafiel was conscious of the one-sided nature of this kind of historiography. After stating that ‘the history of the conquest of Mexico was written by the Spaniards themselves’, he attempted to show an alternative perspective, by giving voice to the post-conquest Aztec chronicler Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc and making ample use of recent archaeological findings. In this early version of a ‘vision of the vanquished’, he relied especially on the writings of the German ethno-historian and linguist Eduard Seler, one of the most respected experts of pre-colonial Mexican culture at the time, and also an active participant at the Congress of Americanists in Paris, where he almost certainly met Peñafiel.Footnote 70 Thus, as several sections in Peñafiel’s Monumentos del arte mexicano antiguo reveal, the design of the Aztec Palace was partially based on the work of this German scholar, whom he called a ‘distinguished friend’.Footnote 71 In spite of his defence of the ‘heroic Aztecs’, he did not wish to fully integrate Aztec history into Mexican national history: ‘What I’m writing is not the history of my country, but merely her great events, and scintillations of her past glory.’Footnote 72

In this sense, Peñafiel sought to construct a Mexican antiquity based on actual archaeological findings and at least partially on recent scholarship, but nevertheless disconnected from the present. What had survived from the pre-Columbian past were some artistic and linguistic elements, but in Peñafiel’s mind the ‘national character’ of modern Mexico was fundamentally shaped by Spanish culture. Echoing the spirit of contemporary Hispanism, he condemned the brutality of the conquest, but separated this tragic historical encounter neatly from Spanish ‘civilization’ in general.Footnote 73 In other words, Peñafiel envisioned the conquest of Mexico as a kind of antique tragedy that gave birth to a new hybrid civilization. The location of the conquest in an almost mythical past becomes even clearer when he cites passages of the Iliad, and compares Cuhautémoc to the heroic Spartan king Leonidas.Footnote 74

As Peñafiel’s writings and his interventions at the Congress of Americanists clearly show, the construction of a Mexican antiquity combined globally circulating knowledge about the pre-Hispanic past with his own ideas about their function in the process of nation-building. Interestingly enough, the congress was sponsored by Brazil’s ousted emperor Dom Pedro II, who had found refuge in Paris and even participated in some discussions on possible earlier dates of the ‘discovery of America’.Footnote 75 However, this and most other contributions lacked sustainable empirical evidence, such as the famed French archaeologist and photographer Désiré Charnay’s paper on architectural and linguistic analogies among ‘ancient civilizations’ in North America, Central America, and Asia.Footnote 76

Peñafiel’s creative visualization of his transnationally constructed Mexican antiquity in the form of the Aztec Palace generated considerable comment in the international press, but not all observers found it convincing.Footnote 77 Many European as well as Mexican art critics and architects criticized the pavilion’s design as too eclectic and exotic to represent a ‘truly national’ style. Consequently, in the aftermath of the fair, Peñafiel’s bold neo-Aztec experiment was overwhelmingly condemned as an expensive failure.Footnote 78 This was mainly due to Mexico’s failure to attract large numbers of migrants through its fair presentations, as its rival Argentina did so successfully. As Rebecca Earle has remarked, ‘potential immigrants were more impressed by the offer of good wages and a recognizably European culture than by an exotic albeit monumental past’.Footnote 79

In the specific historical context of the 1889 fair, it is nevertheless important to interpret the pavilion as the result of complex struggles over the ‘right’ national self-image. The central topic of many visualizations at the fairgrounds was the role of the Indian in Mexican history. Of course, for most intellectuals of the Porfiriato there was no doubt that race and nation were somehow connected, which is why they considered the science of anthropology to be fundamental in understanding how racial factors shaped the country’s destiny. However, intellectuals such as Peñafiel rejected static notions of race that would impede Mexico’s future progress as a modern nation because of its significant indigenous and mixed-race populations. Instead, he and others saw mestizaje as a positive factor for development.

Instead of propagating ‘whitening through immigration’, as Brazil did at the world’s fairs, the Mexican exhibition organizers emphasized the importance of education. Since they generally adhered to liberalism or positivism, they believed that the ‘Indian problem’ could be solved through acculturation and with educational measures. In this sense, they sought to participate in contemporary scientific discourses on race, such as those formulated by the practitioners of physical anthropology, who believed craniometrics and anthropometrics to be adequate tools to measure and categorize the human body, thereby dividing the human race into static sub-units.Footnote 80

Although the majority of Mexican intellectuals did not accept the most radical of these theories, they nevertheless wished to participate in international debates on the ‘race question’, which they perceived as representative of ‘modern science’. Many of them, as Tenorio Trillo has shown, did not hesitate to offer the European and North American anthropologists their much needed ‘raw materials’, derived from ‘primitive societies’. On the one hand, this stance had the paradoxical consequence that Mexico’s anthropological exhibits inside the Aztec Palace were linked to static notions of race and could thus be used to claim the inferiority of huge parts of the Mexican population. On the other, the façade of the building was a perfect visualization of a new mestizaje ideology, indicating that the supposed inferiority could ultimately become an advantage.Footnote 81 The incommensurability of these two racial concepts would only be resolved at the end of the Porfiriato, when the president himself decided to sponsor Franz Boas’s ambitious project to found an International School of Archaeology and Ethnology in Mexico City.Footnote 82 While this institution would not survive the turmoil created by Díaz’s fall and the Mexican revolution, the tide was slowly turning in favour of a more flexible notion of race, as represented by Boas’s cultural relativism.

Although Porfirio Díaz had personally opted for Peñafiel’s Aztec Palace, he seems to have subsequently regretted the decision. Since the dictator was primarily interested in modernization through foreign investment, he wanted to celebrate Mexico’s impressive economic growth, as well as his own image as an ‘enlightened’ ruler.Footnote 83 As a result, he distanced himself from the Parisian display and called for a more ‘modern’ presentation in Chicago. Among other propositions, he wanted Mexico’s national pavilion to resemble a ‘typical hacienda, or residence of a wealthy landed proprietor’.Footnote 84 In the end, however, no national pavilion was built at the Chicago fairgrounds, owing to financial problems.Footnote 85

In general terms, the official Indianism of the Porfiriato was as ambivalent as its Brazilian counterpart. The nationalization of pre-Columbian motives, as at the Paris Universal Exposition, thus took place in the context of violent campaigns against contemporary indigenous groups, such as the rebellious Yucatecan Mayas and the Sonoran Yaquis. In fact, many of Mexico’s natives were among those who lost out as a result of Díaz’s reckless modernization project, especially in the large haciendas of central and southern Mexico.Footnote 86 Thus, Mexico’s official Indianism managed to separate the ‘glorious’ past of the Mayas and Aztecs from the deplorable reality of contemporary indigenous groups. Díaz was nevertheless worried about Mexico’s perceived exoticism at the world’s fairs, as exemplified by the widely mocked Casa Azteca at the Parisian habitation humaine exhibition. As Tenorio Trillo has remarked, Díaz especially feared that Mexican Indians would be ridiculed at the fairgrounds.Footnote 87

However, his desire for a ‘less exotic presentation’ was not fulfilled. Despite a much smaller Mexican presence at the Chicago fair, archaeological and anthropological displays were even more important, and more visible as well.Footnote 88 In spite of Díaz’s wish to avoid the staging of another Indianist performance, as in Paris, his plans were countered by the North American exhibition organizers under the direction of Professor Putnam. In cooperation with Mexican delegates, who installed a small official display in Department M, Putnam and his team staged an unprecedented show of pre-Columbian culture. Such was the impact that Mexico would not be remembered for its numerous minerals, agricultural products, textiles, or machines in various departments, but primarily for its life-size, papier-mâché reproductions of the Mayan ruins of Uxmal and Labna (Figure 4). Organized with the help of Edward Thompson, a hobby archaeologist and the US consul in Yucatán, this display proved to be one of the highlights of the fair, evoking comparisons to classical antiquity and to a ‘forgotten and mysterious race’.Footnote 89 As the authors of A history of the World’s Columbian Exposition summarized in the aftermath of the event: ‘This work was considered a great achievement in archaeology, as nothing of the kind had been done before on anything like so grand a scale.’Footnote 90

Figure 4 William Rand and Andrew McNally, ‘Ruins of Yucatan’. Source: The Columbian Exposition album, Chicago, IL: Rand, McNally & Co., 1893, unpaginated.

As was the case four years previously in Paris, the construction of a Mexican antiquity was a transnational endeavour, though this time the US contribution was clearly dominant, not to say overwhelming. Besides Putnam’s team, which had been sent out to different Latin American countries to gather ‘antiquities’, German researchers from Berlin’s ethnological museum and the Norwegian ethnographer Carl Lumholtz loaned pre-Columbian objects to the Mexican and Central American exhibition in Department M. Even the female pioneer of Mesoamerican archaeology, Zélia Nuttall, contributed her collections of Aztec shields, pottery, feathers, and ancient manuscripts.Footnote 91

As for the Mexican delegation, the authority in charge of the government-sponsored section of ethnology and archaeology was once again Antonio Peñafiel.Footnote 92 In striking contrast to the Paris fair, however, the objects he had gathered for Chicago were far from spectacular and mostly ignored by the international press. The Mexican government exhibit consisted mainly of ceramics, maps ‘illustrating the time of Cortez’, and two model huts of contemporary indigenous groups.Footnote 93 However, some pre-Columbian urns belonging to Mexico’s official exhibit ignited the fantasy of at least one visitor to the exhibition, who claimed that he felt he was ‘looking upon works which had been done by a race of advanced civilization’.Footnote 94

Ironically, despite his worries about an overly ‘exotic’ presentation in Chicago, Porfirio Díaz himself contributed greatly to the imagery of present-day Mexico as an ‘ancient country’ whose pre-Columbian legacy metaphorically lived on in the Porfiriato. This symbolic continuity between the ancient Aztec rulers and Don Porfirio was represented by a throne, which Díaz’s wife, Carmen Romero Rubio, had leased for exhibition in the Gallery of Honour.Footnote 95 The exhibit, which had already been shown at the Paris fair, came from Mexico’s National Palace and depicted the pre-Columbian past as a part of national history: ‘The throne seat is constructed to represent three periods in the history of Mexico. The crown plated with gold typifies the Aztec epoch, and it is carved with signs representing the months, years, and phases of the moon. In the centre is the coat of arms of Mexico.’Footnote 96

Despite Díaz’s sceptical stance towards the display of ‘life Indians’, Putnam’s team eventually welcomed a group of ‘Mexican Indians’ to Department M, who presented their pottery skills at the Midway Plaisance – Chicago’s equivalent to the habitation humaine. It is not clear, however, whether these artisans were ‘Mayas from Yucatan’, as one exhibition guide claimed, or ‘sent by the State of Guadalajara’, as another guidebook indicated.Footnote 97 They were not alone, since Putnam had convinced several foreign governments to bring ‘representatives of many native races’ to the fair.Footnote 98

To summarize, Mexico’s presentations in Paris and Chicago were as ambivalent as the aforementioned Brazilian displays, since both countries sought to integrate the ‘glorious elements’ of the pre-Columbian past into national history, while at the same time rejecting contemporary indigenous cultures. In this respect, however, Mexico’s overall goal was not the gradual ‘whitening’ of its population but rather mestizaje through acculturation and educational measures. As in the case of Brazil, Mexico’s anthropological and archaeological displays were much more visible in Paris, where Antonio Peñafiel and Antonio Anza envisioned the most impressive example of ‘Mexican antiquity’ ever seen at a world’s fair. In Chicago, on the contrary, the country was not even presented through a national pavilion. Instead, the massive reconstructions of the Yucatecan ruins demonstrated that North American anthropologists and archaeologists had effectively ‘conquered’ the field of Mesoamerican archaeology.

Debating Peru’s antiquity

In contrast to Brazil and Mexico, Peru’s participation in the nineteenth-century world’s fairs was rather sporadic and plagued with organizational problems. Because of political and financial difficulties related to the costly war against Chile between 1879 and 1883, Peru was not able to repeat its respected presentations of 1876 and 1878. In fact, the country’s participation at the Paris fair of 1889 was so poor that most international newspapers did not take notice of its presence. The retrospective four-volume official report of the fair even mentions that Peru’s display ‘unfortunately was not what it should have been’, and its tiny display, housed in Uruguay’s pavilion, ‘did not contain much of interest’.Footnote 99 The small exhibit consisted mainly of coffee, cacao, sugar, and rice, as well as coca leaves.Footnote 100

Under the government of Remigio Morales Bermúdez (1890–94), who was generally considered a puppet of the popular military figure and two-time president Andrés Avelino Cáceres (1886–90 and 1894–95), it was felt that this rather embarrassing performance should be forgotten at all cost.Footnote 101 Peru’s participation in the Chicago fair thus offered the chance to show the world that the country had successfully recovered from the war, to demonstrate that great advances had been made in the construction of railroads, and, of course, to celebrate the splendour of the ancient Inca empire. Despite the late institutionalization of archaeology, which occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century, some private collectors and antiquarians were already studying the pre-Hispanic past, especially in the Cuzco area. As Stefanie Gänger has noted, the ancient capital of the Tawantinsuyo was a kind of ‘living museum’, where many European and North American archaeologists and collectors passed by to gather ‘antiquities’. In this sense, late nineteenth-century Cuzco was a transnational hub for the purchase and exchange of pre-Columbian ‘antiquities’, and many of its local collectors participated actively in the global scientific community, as Gänger has also shown.Footnote 102

The interest of a small group of erudite individuals in Lima and Cuzco was, however, not shared by the state, primarily because of political and economic instability in the aftermath of the war.Footnote 103 The situation changed slightly in 1892, when the so-called Junta Conservadora was created with the purpose of controlling the export of pre-Columbian objects more efficiently.Footnote 104 In the same year, the Peruvian government even organized a national preparatory exhibition in Lima in order to select the most adequate pieces for the Chicago world’s fair. It was planned that Peru’s exhibition would comprise manufactured goods, agricultural products, artwork, and a huge array of pre-Columbian objects, such as mummies, pottery, earthenware, and silverware.Footnote 105 Alongside the chosen objects, nine commissioners were also to travel to Chicago in order to supervise the construction of a national pavilion and the presentation of the pre-Columbian exhibits in Department M, as well as in the Bureau of the American Republics.Footnote 106 The guidebooks printed before the opening of the Chicago fair already promised one of the most attractive exhibitions of any of the Latin American countries, comparable only to what was expected from Brazil and Mexico.Footnote 107

In the end, however, Peru’s ambitions resulted in disaster. As mentioned in the retrospective History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, there were ‘magnificent archaeological collections from Peru’ to be seen in Department M, but these were gathered by Putnam’s agents, such as George Dorsey, who was in charge of the section of South American archaeology.Footnote 108 Putnam had sent Dorsey to Chile, Peru, and Bolivia in May 1891, in order to gather ‘antiquities’ and especially mummies.Footnote 109 The resulting display of 125 mummies from the necropolis of Ancón, near Lima, would indeed become one of the Chicago fair’s most successful exhibits.Footnote 110 However, the official Peruvian exhibition, though successfully staged in 1892, never arrived in Chicago. President Bermúdez had originally assigned S/50,000 to the shipment and installation of the complete exhibit in Chicago, but, since Congress refused to make a decision about the clearance of these funds within a reasonable timespan, he issued a decree providing the Exhibition Commission with only the money necessary to fulfil the ‘national desire’ of fair participation.Footnote 111 Eventually, the president’s political enemies brought the matter before the Supreme Court, which decided against the transaction, and thus the Peruvian commissioners ‘were denied the pleasure of appearing at Chicago like the remainder of the world’.Footnote 112 In consequence, the staging of a Peruvian antiquity in Chicago became a decidedly North American affair. As already mentioned, George Dorsey’s ‘Reproduction of a Peruvian burying ground’ was especially celebrated by fair visitors and international journalists alike (Figure 5).Footnote 113 One visitor even claimed that the sight of ‘ancient Peruvian cemeteries, whose hideous mummies, swathed and unswathed, sat in ghastly groups’, had given him nightmares for a week.Footnote 114

Figure 5 ‘Ancient Peruvian burial ground’. Source: Hubert H. Bancroft, The book of the fair, Chicago, IL: The Bancroft Company, 1893, p. 633.

Despite unsuccessful fair participation in Paris and Chicago, in the context of this article the Peruvian case nevertheless merits attention. Even though most pre-Columbian objects in Chicago were gathered and organized by Putnam’s team, the Peruvian side was not completely excluded. For instance, the renowned Cuzco-based collector Emilio Montes travelled to Chicago, where he stayed during the duration of the fair. Probably a participant of the preparatory national exhibition of 1892 in Lima, Montes brought his famous collection of Peruvian ‘antiquities’ to Chicago.Footnote 115 The year before the fair he also published a catalogue of the collection, although it was fairly eclectic and unsystematically organized, even including some pieces from the colonial and republican eras.Footnote 116 Nonetheless, Montes contributed significantly to the Chicago fair with his ‘collection of pottery, wooden vessels, ornaments of gold, silver, and copper, and stone implements and weapons from the Cuzco Valley, Peru, illustrating the time of the Incas’.Footnote 117

Moreover, he and his fellow countryman Manuel Antonio Muñiz were the only Latin American participants in the fair’s international Congress of Anthropology. Though Montes had travelled to Chicago on his own expenses and Muñiz was on an official mission to attend the Pan-American Medical Congress in Washington, DC, and to study the North American system of military hospitals, their presence was regarded as significant, as several comments in the guidebooks and the conference reports show.Footnote 118 Indeed, one guidebook praised Montes’ collection, describing it as ‘beautifully ornamented’, and made to ‘tell us all of the daily life of the Indians of South America’.Footnote 119 His speech at the Congress of Anthropology was, however, hardly compatible with the scientific standards of the day, as compared to the fairly sophisticated interventions of Netto and Peñafiel in 1889. Since Montes was a collector and not an academic, he did not draw on scholarly literature for his knowledge of Peruvian ‘antiquities’. In his conference paper about the ‘antiquity of the civilization of Peru’, he frankly acknowledged that there was no scientific proof for his claim that the ‘Quechua race’ was in fact the ‘oldest civilization of mankind’. He nevertheless expressed his hope that archaeology – understood as a noble and transnational endeavour – would soon unravel the true age of Peru’s ancient civilization, which he estimated at 7,000 years. In the same line as Désiré Charnay in 1889, Montes indicated that possible analogies were to be found in linguistics, as the Quechua and Hebrew languages would share many similarities.Footnote 120

In comparison to US and European scholars who also participated in the congress, such as Zélia Nuttall, George Dorsey, and Carl Lumholtz, Montes’ paper was extremely speculative and completely devoid of empirical proof. This might explain why it was published in the official memoirs but omitted in the otherwise comprehensive conference report by William Henry Holmes in the American Anthropologist.Footnote 121 Although Montes was without any doubt an erudite collector, who showed true interest in the study of pre-Columbian cultures, he was also a salesman. His primary interest for travelling to Chicago was to auction off his collection, which comprised more than 1,200 pieces.Footnote 122 In this context, he probably saw the Congress of Anthropology as a promotional platform, which allowed him to praise the uniqueness (and thus the monetary worth) of his ‘Peruvian antiquities’. Montes knew that the exhibits in Department M would form the basis for the Columbian Museum of Chicago, today’s Field Museum. On 9 September 1893, the museum purchased his collection, as his correspondence with Frederic Putnam proves. In fact, Montes was pressuring Putnam to buy his collection without delay, claiming that he had to depart immediately to attend to urgent matters at home.Footnote 123

In contrast to Montes’ ambiguous interests, the time that Manuel Antonio Muñiz spent in Chicago was clearly motivated by scientific reasons, since his government-sponsored mission was charged with collecting statistical data on the US health system, as well as establishing contacts with US anthropologists, statisticians, and physicians.Footnote 124 According to the conference report that Holmes submitted to the American Anthropologist, Muñiz – at the time surgeon general of the Peruvian army – ‘exhibited a remarkable collection of crania illustrating prehistoric trephining’.Footnote 125 His paper delivered at the conference was later published in the form of a ‘summary statement’ in an essay on ‘Prehistoric trephining in Peru’, co-authored by the North American anthropologist William John McGee.Footnote 126 In the preface to this essay, McGee related how Muñiz was primarily responsible for the gathering of the material, which stemmed from his extensive travels ‘through the ancient land of the Incas’.Footnote 127 The resulting collection comprised more than a thousand skulls, of which nineteen were trephined – that is, showed surgical perforations in various forms on the cranium’s surface. Muñiz had brought these crania to the Chicago fair, in order to demonstrate how the operation of trephining was performed and the tools used. It seems that his display left quite an impression on the congress attendees, and William Holmes even regarded Muñiz’s collection as ‘the richest ever made’.Footnote 128

However, McGee left no doubt that the work of his collaborator was intellectually inferior, since the Peruvian had not interpreted the findings according to the latest science. Thus he discounted Muñiz as an adventurer without scientific ambitions, claiming the ‘authorial responsibility’ for almost the whole essay for himself.Footnote 129 Yet a close reading of Muñiz’s contribution shows that the Peruvian physician was by no means a mere submitter of data, even though he compared the surgical techniques of Peru’s ancient cultures to those of the Greeks and Persians. In the rest of his ‘summary statement’ he showed great knowledge of pre-Columbian trephination, its possible cultural contexts, and the applied techniques, and he even commented that these operations were never performed on the dead or carried out with the purpose of using the bone fragments as amulets, as various authors had falsely claimed. In one part, he cited the works of various international specialists on the matter, in order to strengthen his hypotheses through academic authority.Footnote 130 It is thus very likely that McGee deliberately downplayed the role of Muñiz in the work of contextualizing and interpreting the findings. To some degree, the appropriation of Muñiz’s contribution by a North American anthropologist can be regarded as symptomatic of the epistemic violence exerted against non-institutionalized forms of knowledge in the imperialist context of the fairs. At the same time, however, collectors such as Muñiz and Montes regarded pre-Columbian burial sites primarily as ‘treasures’, implicitly extending a similar kind of epistemic violence towards the indigenous cultures of their own country.

In contrast to Mexico and Brazil, Peru’s participation in the exhibitions of 1889 and 1893 was plagued by huge financial and organizational difficulties. Although on both occasions the Peruvian government failed overall to deliver a satisfying presentation, the Peruvian mummies at the Chicago fair nonetheless comprised one of the most impressive and acclaimed displays. However, the famed mummy exhibit was a decidedly North American endeavour, with only minimal involvement from the Peruvian side. Even though two Peruvian citizens participated in the international Congress of Anthropology in Chicago, their vision of a ‘Peruvian antiquity’ was not generally treated with the same respect as had been previously shown to the Mexican and Brazilian delegates. Thus, their contributions were either silenced or quietly appropriated.

Conclusion

As I have shown in the cases of Brazil, Mexico, and Peru at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition and the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, it is impossible to fully grasp the construction of national self-images without taking the scientific debates ‘behind the scenes’ into account. In the last third of the nineteenth century, the focus on Indianist themes, such as Brazil’s celebration of the ‘noble savage’ or Mexico’s monumental Aztec Palace, became increasingly science-based. In many cases, the accompanying anthropological and archaeological displays were the result of academic debates between European, North American, and Latin American attendees to international congresses, which took place at the fairgrounds. At these meetings, different interpretations of Latin America’s past were debated and eventually visualized in the form of ethnographic and archaeological exhibits. Therefore, the world’s fairs cannot simply be understood as international platforms, where a national elite designed idealized images of their nations under construction. The creation of reified images of the modern nation was, of course, one of the core characteristics of these events. However, the fairs also contributed to the exchange of persons, objects, and globally circulating scientific knowledge, thus serving as transnational hubs for contemporary nation-builders.

By understanding the late nineteenth-century fairs as spaces of global knowledge, I argue that cosmopolites like Ladislau Netto and Antonio Peñafiel were not just respected members of the scientific community but also capable of contradicting commonly accepted theories on racial degeneration or Latin America’s supposed lack of history. Through studying the pre-Columbian past, both sought to provide the modern nation-state with a mythical origin. Their narratives were based not only on the latest findings of European and North American scientists but on their own research as well. The integration of the pre-Columbian past into national history was, however, ambiguous and pervaded by epistemic violence, since the growing knowledge of ancient civilizations contributed to the stigmatization of contemporary indigenous groups, whose culture appeared to be disconnected from the once ‘glorious’ past.

As the case of the Peruvian delegates in Chicago demonstrates, this kind of epistemic violence could rebound against the Latin American fair participants themselves. Thus, in the context of an expansionist Pan-Americanism, North American institutions began to dominate the fields of anthropological and archaeological research, extending their reach to Latin America, where they conducted the most important excavations and field studies. The results were usually claimed as conquests of ‘American science’, and a great part of the findings ended up in North American museums and institutions. Alongside this form of cultural imperialism, North American and European congress attendees also tended to diminish the contributions of their Latin American peers, frequently reducing them to mere collectors and data submitters, as the cases of Emilio Montes and Manuel Antonio Muñiz illustrate.

In this regard, it is important to keep the limitations of cultural and scientific exchange on the fairgrounds in mind. Trapped between the European and North American need for exoticism and the less than subtle epistemic imperialism of ‘Northern’ scientific institutions, collectors such as Montes and Muñiz, as well as academics such as Netto and Peñafiel, were nevertheless able to contribute substantially to global debates on pre-Columbian and contemporary indigenous cultures. From a present-day standpoint, many of their theories – such as the insistence on prehistoric contact and linguistic analogies between Asian, European, and American ‘high cultures’ – may seem speculative and pseudo-scientific. Ladislau Netto was even mocked during his lifetime for assuming prehistoric contact between the Phoenicians and indigenous groups in north-eastern Brazil.Footnote 131 We should not forget, however, that these and similar theories were widely accepted by leading nineteenth-century archaeologists and anthropologists, such as Désiré Charnay. In this sense, Latin Americans were important agents in the transnational endeavour to (re-)construct the pre-Columbian past. Though many of their hypotheses would be dismantled by twentieth-century science, their notion of a Latin American antiquity, as visualized at the fairgrounds, proved to be a powerful element of nation-building.

Sven Schuster is Professor of History in the School of Human Sciences at the Universidad del Rosario, Colombia. He obtained his PhD (2009) and his postdoctoral lecture qualification (2014) in Latin American history from the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, Germany. His areas of interest are Latin American history (especially Brazil and Colombia), transnational history, historical memory, and visual culture.