Part I - Sceptics

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 April 2013

Summary

This first part of our book offers essays about claims that have been made on behalf of various individuals as alternative authors of the works more generally attributed to Shakespeare. Until the early years of the twenty-first century such claims were thought to have originated around 1785, over 150 years after Shakespeare died, in the work of a Warwickshire clergyman named James Wilmot (1726–1828). This belief originated in an article by Professor Allardyce Nicoll published in 1932 in the Times Literary Supplement entitled ‘The First Baconian’ which describes two lectures reportedly given before the Ipswich Philosophical Society by one James Corton Cowell in 1805. They claim that Wilmot amused himself in his retirement by trying to write a life of Shakespeare and tell how, losing faith in Shakespeare, he constructed a theory that the true author of the works was Francis Bacon. But in old age, Cowell reported, Wilmot instructed his housekeeper to burn his papers. His story would have been lost to posterity had he not previously confided it to Cowell, whose lectures were preserved in the University of London Library. But James Shapiro, in his invaluable book Contested Will, follows up suspicions about the authenticity of the documents first expressed in the anti-Shakespearian journal Shakespeare Matters 2 (Summer 2003) which show that the lectures draw on information, and even vocabulary, which was not available in Cowell's time. Nor is there any other evidence that Cowell, or the Ipswich Philosophical Society, ever existed. Only one conclusion is possible: the lectures are forgeries, and Nicoll was deceived by them. Even Shapiro doesn't know who perpetrated the fraud, or why. He guesses that it may have been done for money or have originated in ‘the desire on the part of a Baconian to stave off the challenge posed by supporters of the Earl of Oxford’. Furthermore, the deception ‘reassigned the discovery of Francis Bacon's authorship from a “mad” American woman to’ – and here Shapiro silently quotes Richard II 1.3.272 – ‘a true-born Englishman’. As a result of these discoveries, the anti-Shakespearian movement must now be pushed forward to the middle of the nineteenth century.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

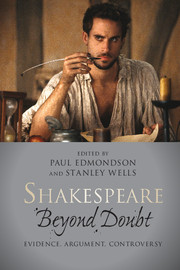

- Shakespeare beyond DoubtEvidence, Argument, Controversy, pp. 1 - 4Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2013