Densely covered with text that seems to strain against both the wide margins and the central image, this folio comes from the so-called Summa Aurea, or the Golden Summa. It was penned by canon (Church) law professor, bishop, and cardinal Henry of Segusio (or Susa, in northern Italy), best known as Hostiensis (d.1271). The “summa” was the chief form of medieval university scholarship. Our word “summation” derives from the same root and suggests the scope of such treatises, which attempted to cover a huge panoply of knowledge on various topics in a systematic way. Henry’s Summa took up the many canon laws issued by Pope Gregory IX (d.1241). It was extremely popular, surviving in two versions and many copies, scores of them made after Henry’s death. Indeed, it was so highly regarded that in 1477 admirers gave it the moniker “golden,” even though Henry called it, quite simply, “my summa.”

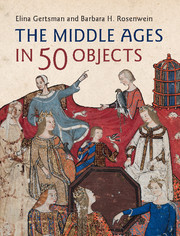

The page here features a consanguinity tree—a complex diagram that works out degrees of kinship among family members related by blood. In the keyhole-shaped opening, a crowned man stands holding the table filled with roundels that are inscribed with words for blood relations and numbers showing degrees of consanguinity. The man, known as Ego (or “I”), reappears in the central medallion, still crowned, at bust length: he is the anchor in this visual scheme. The roundel above his bust contains the abbreviation for the words pater (father) and mater (mother), while the medallion below his head is inscribed filio (son) and filia (daughter). Both roundels are marked with the Roman numeral i, which indicates one degree of separation from Ego. To Ego’s left and right are the roundels for his (or her) brother and sister, which are marked ii to indicate two degrees of separation. The shaft of the arrow-like diagram has medallions that extend vertically, following Ego’s direct genealogical line, all the way down to his great-great-grandchildren. Aunts and uncles, nieces and nephews, second and third cousins find their place in this table as well. The family tree thus comprehends a vast array of kinships, each marked by a number used to calculate and regulate proper marital relations. Sometimes such tables of consanguinity were accompanied by or elided with tables of affinity, which featured a couple and listed their relatives by marriage.

Churchmen had two good reasons for controlling marital relationships. One had to do with property, which—along with authority—passed from family members to the next generation. In the early Middle Ages, the custom was for every member of the family to inherit property, even women, though normally their share was lesser. The Church, too, claimed inheritances. It taught that nothing could be better for the wealthy than to give their property to monks, who would pray for the soul of the donor, or to churches where the relics of the holy saints lay, ready to perform miracles.

Most importantly, however, the Church had the moral duty to regulate how the family was constructed. In the early Middle Ages, marriages had nothing to do with the Church—at least from the laity’s point of view. There were no “church weddings,” and marriages were private family arrangements. But very early on the Church tried to interfere with this. In the first place, it ordered priests to be celibate, though this was not the norm until the twelfth century; and, in the second place, it demanded, often with the support of kings, that certain restrictions apply to marriageable partners. “And we instruct and pray and enjoin, in the name of God, that no Christian man shall ever marry among his own kin within six degrees of relationships,” declared the eleventh-century laws of King Cnut, written in the Anglo-Saxon language for even non-Latinate English men and women to read and absorb. Marrying “among kin” within those degrees was considered incest, a terrible sin. The figure in the Golden Summa may wear a crown, but one did not need to be a king to be affected by such laws.

While diagrammatic tables were not absolutely necessary to figure out degrees of consanguinity, they were certainly useful and utterly appropriate for books about canon law. The particular laws that Henry commented on had been compiled on directives of Gregory IX in 1230 in order to replace all earlier collections of canons. The section on consanguinity responded to changes in the canon law on that topic introduced by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. By then, noble families, who intermarried constantly (not to mention peasants, who were largely rooted to their manor), found it nearly impossible to find mates within the required degrees of separation, which by then numbered seven. A slew of divorces resulted from “sudden” discoveries of forbidden blood relations. To solve these problems, Fourth Lateran changed the number of prohibited degrees of consanguinity from seven to four, returning to the number originally prescribed by Roman civil law. But whereas Romans counted degrees of consanguinity up from the individual all the way to the common progenitor and then back down to the potential partner, medieval canon law calculated the degrees by counting up to the common progenitor for both prospective spouses. What constituted four degrees of separation for Romans became two for medieval Christians. Marriage between first cousins, in other words, was illegal. In order to safeguard against an accidentally incestuous marriage, noble families were encouraged to keep track of their genealogies.

The man at the center of this consanguinity tree is visually enjoined to be the master—indeed, the king—of self-control and familial organization. He stands tall, with his toes overlapping the frame and with the trefoil inscribed into the circular opening suggesting a halo around his head. Vine tendrils that grow out of the arrow-like chevron allude to the vegetal metaphor of the genealogical tree that was itself an apt metaphor for the fruitful Christian family. And yet, the man does not so much hold the diagram as he is pinned to the background by its upward thrust, rooted in place by its rigid rules of kinship dictated by the canon law.

Such diagrams suggest the pivotal role that the Church played in the everyday lives of medieval Christians. While religion was important to the laity even in the early Middle Ages, the eleventh and twelfth centuries saw a deepened desire on the part of many to conform their lives to that of Christ and to listen ever more avidly to the preaching of the Church. Meanwhile, the Church reformed itself, ending abuses like simony (buying Church offices) and clerical marriages or other carnal unions. New monastic movements offered persuasive models for lives of piety, and scholars of the new universities, just forming at this time, offered good reasons for seeking God’s grace through Church sacraments. Canon law was systematized at this same time, the papacy gained new power, the crusades called men (and women too) to give their lives in the service of a Church-sponsored army, and, in short, all the developments of the period made it imperative for the laity to listen to churchmen.

Both the canon law and its diagrammatic depictions hid a tender emotional truth: already in the twelfth century people were praising marriage for love. In the poem Floris and Blanchefleur (c.1160s), the two protagonists are brought up together, love one another, are separated, and, after many adventures, wed. In the thirteenth-century Middle English version of the story, “Floris falls at his feet and prays [the emir] to give him his sweetheart. The emir gave him his lover; everyone who was there thanked him then. He had them brought to a church and had them wedded with a ring.”