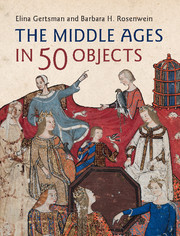

Two ferocious-looking people, a man and a woman, flank a demon—a div in Persian, jinn in Arabic—who is secured by a chain. The man wears a tasseled hat with a rosette, knee-length trousers, a long-sleeved jacket, and soft shoes. He holds one end of the chain in his right hand and raises his left arm as if to strike the demon with his club. The whites of his eyes, and his light gray beard and moustache, gleam against his dark skin. The woman, on the other side of the demon, appears to be a hybrid, half-human and half-animal, her physiognomy not much less grotesque than that of the div she has captured. She holds a length of the chain in both hands, raising it close to her face and particularly her mouth, as if to examine it or even gnaw at it. Her long, narrow red mouth with pale lips echoes her eyes: the red of the irises and the white of the sclera. Dressed in a long cloak and dark red scarf, she nonetheless remains barefoot, and her feet have huge toenails, just like the demon’s. The demon himself towers above his captors, with the chain part of a gold ring encircling his neck, and with other rings around his forearms and ankles. Nude except for a short skirt, he turns his great fleshy head toward the man. His crescent-shaped eyes express deep grief, his fanged mouth is downturned, his face lined with wrinkles; the pointed ears, deer-like horns, a trunk-like protrusion extending down from his chin, and the long tail wrapped around his right leg leave no doubt about the monstrous identity of the captive.

The painting comes from one of two albums formerly owned by the early Ottoman sultans and now in the Topkapı Palace library in Istanbul. Sixty-five of the paintings and drawings were later inscribed with the name Muhammad Siyah Qalam, or Muhammad Black Pen. Perhaps the name refers to one artist, or perhaps it was a sobriquet for a group of them. The albums themselves are a miscellany and contain images that hark back to a wide variety of styles, showing Persian, Mongolian, and Chinese sources alike. No textual parallels exist for these images, which appear to be independent creations—neither parts of a particular manuscript nor illustrations of a recognizable story. Siyah Qalam mainly painted demons, monsters, dervishes, shamans, and so-called “nomads” or “wanderers” (also variously identified as Kipchaks, Russians, Mongols, and Turks). The images are dominated by dark colors and heavy lines and feature highly animated figures set against blank ground on unsized, unpolished paper, and painted in a limited range of colors. This is precisely the style of this painting, which, however, does not bear the artist’s name.

Miscellanies like the Istanbul albums are not as curious as they seem. In the thirteenth century, under the leadership of Chinghis (or Genghis) Khan (d.1227), various tribes in Mongolia came together to create the largest contiguous empire ever known. Conquering China by 1279 and southern Rus’ (from today’s Kazakhstan through Ukraine) in the 1230s, the Mongols proceeded on to Poland and Hungary, where they finally stopped. Another branch of the Mongols took over the Islamic world, moving across Iran all the way into Anatolia (Turkey) and Iraq. Only the Mamluks of Egypt halted their westward push. Violent and sudden as the Mongol drive was, it ultimately opened up lively trade and travel routes between the west and far east. When the Mongols began to rule in China, they brought with them Muslim artists and craftsmen, who both adopted and transformed Chinese motifs. While the Chinese branch of the Mongol Empire ended c. 1350 with the Ming dynasty, Iran remained under Mongol rule—the Timurids, heirs of Timur the Lame or Tamerlane (d.1405)—until the beginning of the sixteenth century.

Eurasia, c. 1400.

Venetian and Genoese traders made it their business to frequent the region, which was enormously prosperous. Already by the early fourteenth century the Iranian Mongol rulers had converted to Islam. The art that they and their contemporary elites supported drew on the traditions of the whole Eurasian continent. The arts also flourished in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries under the rule of the Timurids, known for their architecture, metalwork, and especially for their astonishing book production that included enormous Qur’an manuscripts, historical chronicles, and collections of fables and poems. Among these manuscripts are sumptuous versions of Kalila wa Dimna, a cycle of fables that originated in India; the tenth-century Ferdowsi’s mytho-historical epic Shahnameh; and Nizami Ganjavi’s poetic masterpiece Khamsa. Some of the finest workshops were located in Herat. It was perhaps there or in nearby Central Asia that the demon in chains was painted.

Demons hold pride of place in the medieval Islamic imaginary, and they became a particularly popular subject matter in painting in the later Middle Ages. The ideas about these supernatural creatures were inherited from pre-Islamic Persia—where the div could be not only a demon but also a giant and sometimes even Satan himself—and Arabia, where the demons were believed to have been shapeless and invisible. Islamic demonology of the era described two sorts of angels: the loyal ones who guided people to God, and the disobedient, who seduced them away. The fallen angels married human women, producing children knowledgeable in sorcery. Somewhere between the good and the evil spirits were the Peris; beautiful and beneficent, akin to the “fairies” of European folklore, they could be fierce and change form, to look like monsters and demons. Their main enemies were the true demons, the divs, as well as sorcerers and witches, who contained them within magic circles and chained them up. The origin of divs was not always clear; Persian philosopher al-Razi (d.925) conjectured that evil spirits, or the souls of the wicked, turn into demons.

But the jinns were not just folk inventions or subjects of philosophical meditation; they are mentioned throughout the Qur’an, and an entire sura, or chapter, is dedicated to them. There the jinns are allowed to speak for themselves:

Demonic presence is striking in manuscripts that recount the Prophet Muhammad’s mystical journey to hell, or Jahannam (derived from the Hebrew word Gehenna). The Qur’an describes the blazing fires and boiling waters, the smoke and the winds of hell, which is composed of seven levels. At times, the place is styled as if a living monster: also called “the Crusher” (al-hutama), it sighs and speaks. Hadith, the gathering of the Prophet Muhammad’s sayings and teachings, elaborates on Jahannam’s punishments, and mentions a section of it that is freezing cold rather than hot. Further taxonomy of hell’s environment and punishments comes from a variety of the so-called eschatological manuals. Jahannam, the complete opposite of al-Janna, the garden of paradise, was seen as the post-Judgment destination for sinful people and jinns alike. The wicked jinns will be the first to enter Jahannam and will be relegated to its lowest level—the most terrifying one of all. There, these naturally fiery creatures will be fettered together by chains and, some commentators suggest, will be punished by extreme cold. Chief among them will be Iblis—the fallen angel, Satan himself.