Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of maps

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Colonisation and contact

- 1 What really happened to Old English?

- 2 East Anglian English and the Spanish Inquisition

- 3 On Anguilla and The Pickwick Papers

- 4 The last Yankee in the Pacific

- 5 An American lack of dynamism

- 6 Colonial lag?

- 7 “The new non-rhotic style”

- 8 What became of all the Scots?

- Epilogue: The critical threshold and interactional synchrony

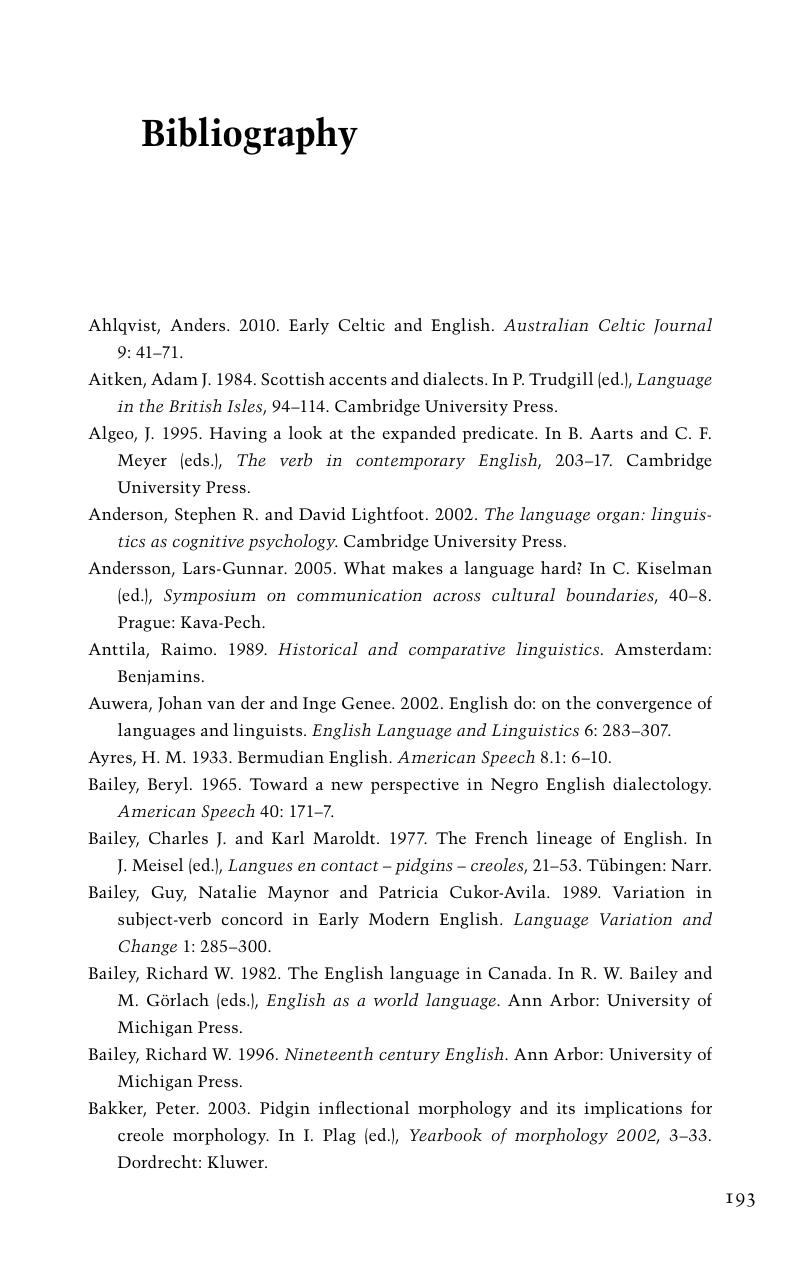

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 December 2010

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of maps

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Colonisation and contact

- 1 What really happened to Old English?

- 2 East Anglian English and the Spanish Inquisition

- 3 On Anguilla and The Pickwick Papers

- 4 The last Yankee in the Pacific

- 5 An American lack of dynamism

- 6 Colonial lag?

- 7 “The new non-rhotic style”

- 8 What became of all the Scots?

- Epilogue: The critical threshold and interactional synchrony

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Investigations in Sociohistorical LinguisticsStories of Colonisation and Contact, pp. 193 - 211Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2010