Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Chronological List of Grimmelshausen's Works and Their First English Translation

- Introduction

- I Basics

- Problems in the Editions of Grimmelshausen's Works

- Grimmelshausen's “Autobiographies” and the Art of the Novel

- Allegorical and Astrological Forms in the Works of Grimmelshausen with Special Emphasis on the Prophecy Motif

- Grimmelshausen and the Picaresque Novel

- Grimmelshausen's Ewig-währender Calender: A Labyrinth of Knowledge and Reading

- Grimmelshausen's Non-Simplician Novels

- In Grimmelshausen's Tracks: The Literary and Cultural Legacy

- II Critical Approaches

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Grimmelshausen's “Autobiographies” and the Art of the Novel

from I - Basics

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 April 2017

- Frontmatter

- Contents

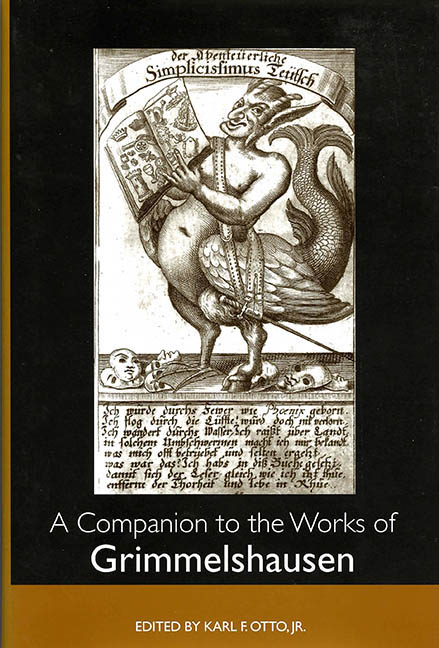

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Chronological List of Grimmelshausen's Works and Their First English Translation

- Introduction

- I Basics

- Problems in the Editions of Grimmelshausen's Works

- Grimmelshausen's “Autobiographies” and the Art of the Novel

- Allegorical and Astrological Forms in the Works of Grimmelshausen with Special Emphasis on the Prophecy Motif

- Grimmelshausen and the Picaresque Novel

- Grimmelshausen's Ewig-währender Calender: A Labyrinth of Knowledge and Reading

- Grimmelshausen's Non-Simplician Novels

- In Grimmelshausen's Tracks: The Literary and Cultural Legacy

- II Critical Approaches

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

The New Element in Narrative Form

With Grimmelshausen's Simplician novel cycle, which consists of Simplicissimus Teutsch, Continuatio, Courasche, Springinsfeld, and Vogelnest I–II, the German novel of the early modern age attains the level of world literature. The novels, appearing in rapid succession over a period of seven years (1668–1675), present a goldmine of masterfully narrated biographies and successfully executed fictional autobiographies. This is all the more surprising since before Grimmelshausen the novel in the German-speaking world, especially in the form of first person narratives, was without support in the poetic handbooks of the time and actually did not exist in any form worth mentioning. The only narrative tradition accessible to Grimmelshausen was that of the pícaro in the German variation of Aegidius Albertinus (1560–1620), Der Landstörtzer Gusman von Alfarche oder Picaro genannt (Munich 1615) and the anonymous translation of Lazarillo de Tormes in Zwo kurtzweilige lustige vnd lächerliche Historien (Augsburg 1617). Both, however, constitute only one aspect of Grimmelshausen's narrative universe and cannot by themselves reveal the multiplicity of Simplician interwoven autobiographies in novel form. The narratives of Grimmelshausen, which revolve around characters who thematize themselves, are based on other presuppositions and have other goals.

War as Theme

Grimmelshausen announces his first novel Der Abentheurliche Simplicissimus Teutsch (1668) at the end of the tract entitled Satyrischer Pilgram (1667). There one can read what follows in the “Nachklang” to “Zehenden Satz / vom Krieg”:

Jch gestehe gern / daß ich den hundersten Theil nicht erzehlet / was Krieg vor ein erschreckliches und grausames Monstrum seye / dann solches erfordert mehr als ein gantz Buch Papier / so aber in diesem kurtzen Wercklein nicht wohl einzubringen wäre / Mein Simplicissimus wird dem günstigen Leser mit einer andern und zwar lustigern Manier viel Particularitäten von ihm erzehlen. (160)

Grimmelshausen's announcement that he prefers the novel for treating the theme of the war stems from his conviction that one cannot get at the horror of war only by reasoning. Even a critically engaged discussion, as found for example in pamphlets written by Erasmus von Rotterdam (1466–1536) and Sebastian Franck (1499–1542 or 1543) at the beginning of the sixteenth century, must have seemed insufficient to Grimmelshausen after a thirty-year war. He must have arrived at the realization that this war, which depleted and demoralized the civil population like no earlier conflict in European history, cannot be spoken of as an object.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Companion to the Works of Grimmelshausen , pp. 45 - 92Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2002