3 - “Ready to Die for Liberty”

Expanding the Boundaries of Freedom

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 July 2014

Summary

They Know Everything that Happens

Blacks throughout the country – North and South, free and enslaved – rejoiced as word of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation spread. Despite its limited nature, it was astonishing to see such a document coming from a president who had once supported a constitutional amendment guaranteeing slavery forever. In little more than a year, blacks had forced Lincoln and the country further toward the right side of history. They still had some way to go, but black folk would continue pointing the way. The Emancipation Proclamation may have been signed with Lincoln’s pen, but blacks were its author. They would take ownership of the document and make it much more than it was. Within days of the preliminary Proclamation’s announcement on September 22, slaves were escaping to Union lines and claiming its promise of freedom months before it went into effect. The editors of the New York Times wrote on September 28 that there must surely be “a far more rapid and secret diffusing of intelligence and news through the plantations than was ever dreamed of at the North.”

On January 1, 1863, at prayer meetings across the South and mass meetings across the North, blacks and their white abolitionist allies celebrated the day of “Jubilee.” A huge crowd packed Boston’s Music Hall for a celebratory concert. At nearby Tremont Temple, there were three meetings that day – morning, afternoon, and evening – all of which packed the house. Among the speakers were black abolitionists William Wells Brown, John Rock, and Frederick Douglass. William C. Nell – journalist, author, and, as a Boston postal clerk, the first black ever to serve in the federal civil service – spoke of the day as a turning point in the lives of enslaved Americans. “New Year’s day – proverbially known throughout the South as ‘Heart-Break Day,’ from the trials and horrors peculiar to sales and separations of parents and children, husbands and wives – by this Proclamation is henceforth invested with new significance and imperishable glory in the calendar of time.”

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

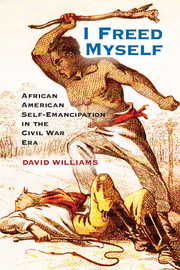

- I Freed MyselfAfrican American Self-Emancipation in the Civil War Era, pp. 114 - 160Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014