Introduction

Following the Footsteps of the Slaves

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 July 2014

Summary

They Are Freeing Themselves

Duncan Winslow escaped from slavery in Tennessee during the Civil War and eventually joined the Union army. April of 1864 found him along the Mississippi River with the Sixth U. S. Heavy Artillery defending Fort Pillow, Tennessee, from attack by General Nathan Bedford Forrest and his Confederate cavalry. Outnumbered nearly four to one, the defenders were quickly overwhelmed. As rebel troops overran the fort, Winslow and his comrades threw down their arms and tried to surrender, but Forrest’s men took few prisoners. In what came to be known as the Fort Pillow Massacre, Confederates slaughtered nearly 300 of their captives, most of them former slaves. To rebel officers’ shouts of “Kill the God damned nigger,” Winslow was shot in his arm and thigh. In the confusion, he managed to escape by crawling among logs and brush, hiding there until the enemy moved on. When darkness fell, Winslow made his way down to the riverbank and boarded a federal gunboat.

After his release from a military hospital in Mound City, Illinois, Winslow settled on a farm three miles west of town, where he raised garden vegetables and sold them house to house. One day a candidate for local office asked Winslow for his support in an upcoming election. As if to seal the deal, the candidate remarked, “Don’t forget. We freed you people.” In response, Winslow raised his wounded arm and said, “See this? Looks to me like I freed myself.”

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

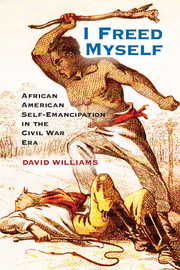

- I Freed MyselfAfrican American Self-Emancipation in the Civil War Era, pp. 1 - 17Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014