Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Complicity in False Arrest, Imprisonment and Theft by a Fairtrade-Certified Company

- Chapter 2 Hindrances to Access to a Remedy in Business-Related Cases in Colombia: The Case of Gilberto Torres

- Chapter 3 The Global Pursuit for Justice for DBCP-Exposed Banana Farmers

- Chapter 4 The Rupturing of the Dam and the Community’s Social Fabric: A Testimony from an ‘Atingido’ from Bento Rodrigues, Brazil

- Chapter 5 Taming the Dragon, Unpacking Options for Access to Remedy for Violations by Chinese Multinational Corporations Operating in Chiadzwa, Zimbabwe

- Chapter 6 Máxima Acuña: The Story of How a Business Impacted Human Rights Defenders

- Chapter 7 Community Interrupted, ‘Life Projects’ Disrupted: Cajamarca, Ibagué, and the La Colosa Mine in Colombia

- Chapter 8 Occupational Health as a Human Right: A Case Study in a Turkish Free Trade Zone

- Chapter 9 The Price of the ‘Black Dollar’: Veteran Coal Miners and the Right to Health

- Chapter 10 Abandoned: A Tale of Two Mine Closures in South Africa

- Conclusion

- Appendices

- List of Contributors

- Index

Chapter 7 - Community Interrupted, ‘Life Projects’ Disrupted: Cajamarca, Ibagué, and the La Colosa Mine in Colombia

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 January 2022

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Complicity in False Arrest, Imprisonment and Theft by a Fairtrade-Certified Company

- Chapter 2 Hindrances to Access to a Remedy in Business-Related Cases in Colombia: The Case of Gilberto Torres

- Chapter 3 The Global Pursuit for Justice for DBCP-Exposed Banana Farmers

- Chapter 4 The Rupturing of the Dam and the Community’s Social Fabric: A Testimony from an ‘Atingido’ from Bento Rodrigues, Brazil

- Chapter 5 Taming the Dragon, Unpacking Options for Access to Remedy for Violations by Chinese Multinational Corporations Operating in Chiadzwa, Zimbabwe

- Chapter 6 Máxima Acuña: The Story of How a Business Impacted Human Rights Defenders

- Chapter 7 Community Interrupted, ‘Life Projects’ Disrupted: Cajamarca, Ibagué, and the La Colosa Mine in Colombia

- Chapter 8 Occupational Health as a Human Right: A Case Study in a Turkish Free Trade Zone

- Chapter 9 The Price of the ‘Black Dollar’: Veteran Coal Miners and the Right to Health

- Chapter 10 Abandoned: A Tale of Two Mine Closures in South Africa

- Conclusion

- Appendices

- List of Contributors

- Index

Summary

Introduction

First of all, I was born in Cajamarca but I have lived all my life in Ibagué because my family, when I was a child, was forcefully displaced from Cajamarca during the political violence during the ‘40s and ‘50s in Colombia. I am a forestry engineer and I used to work for the Ministry of Tolima, and I have dedicated myself full-time for the last 9 years to defend Cajamarca in the case of the mining.

‘Jorge Enrique’, not his real name, sits across from me in a restaurant of his choosing with maps and newsletters. He is one of two leaders of Eccoterra, a local group opposed to the development of a mine in and around Cajamarca, Tolima Department, Colombia, by AngloGold Ashanti, the South African mining giant. There are several opposition groups in the towns surrounding the Tolima capital of Ibagué but the ones I am introduced to are Eccoterra and Comité Ambiental de Cajamarca.

That Jorge Enrique had been fighting for nine years to preserve a community he was displaced from as a child struck me. It reminded me of something an older man had said to me the day before. A member of the Comité had almost joked when he said, ‘It is no longer going to be said that time is gold, but that time is water.’ The proposed mine was having a significant effect on the way local environmental and human rights defenders (‘E-HRDs’ or ‘defenders’) were spending their lives. The Comité member viewed both water and time as precious, but to protect the water they had to sacrifice their time.

I visited Ibagué in May 2016 to examine the impact of the intended La Colosa mine, whose trailings (mine waste) would reportedly flow from Cajamarca through Ibagué and into another village, Piedres. Literally translating to ‘the Colossus mine’, it was expected to be the largest gold mine in Latin America.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

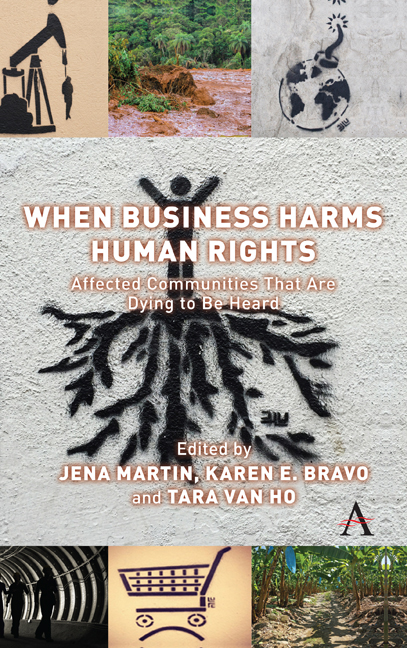

- When Business Harms Human RightsAffected Communities that Are Dying to Be Heard, pp. 109 - 136Publisher: Anthem PressPrint publication year: 2020