1.1 Air Pollution Kills: Particulates Matter!

Difficulty breathing, weight gain, reduced productivity, clouded judgement, suppressed performance at work or school, or a depressed mood – we typically attribute these symptoms to sleep deprivation, poor nutrition, or family stress, but many of us might be surprised to learn that another major explanation is literally in the air we breathe.

Dirty air is more prevalent than one might think. According to the 2018 report State of Global Air, more than 95 percent of the world’s population resides in areas that fail to comply with the air pollution safety standards set by the World Health Organization (Health Effects Institute 2018). From Los Angeles to Kampala, from Delhi to Beijing, air pollution destroys our health and shortens our lives to a far greater degree than violence, diseases such as AIDS and malaria, and smoking (Reference Lelieveld, Pozzer, Pöschl, Fnais, Haines and MünzelLelieveld et al. 2020).

Air pollution is a silent and invisible mass murderer that claims around seven million lives – one out of every eight deaths each year – making it the deadliest environmental health hazard (WHO 2018). The rapid decline in air quality has been one of the most pressing yet understudied challenges facing humanity in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa in recent decades. Children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable to the adverse health effects of air pollution, and researchers have estimated that dirty air is responsible for one in five infant deaths in sub-Saharan Africa (Reference Heft-Neal, Burney, Bendavid and BurkeHeft-Neal et al. 2018). Worse still, breathing dangerously polluted air, especially particulate matter (PM) that is linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, increases the probability of succumbing to COVID-19, and such an effect is particularly pronounced among the socially disadvantaged (Reference Wu, Nethery, Sabath, Braun and DominiciWu et al. 2020; Reference Austin, Carattini, Mahecha and PeskoAustin et al. 2020; Reference Persico and JohnsonPersico and Johnson 2020). Given its nexus with climate change, air pollution is unarguably one of the most significant threats to human survival and well-being in the twenty-first century.

1.2 Containing the Invisible Killer: Variation in Success

Having recognized the gravity of the problem, leaders worldwide are waging war on air pollution. For instance, in the United States, public outcry over a series of pollution accidents – most notably in Donora, Pennsylvania – and a better understanding of the causes of air pollution contributed to the passing of the first federal legislation related to air pollution, the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955, at the behest of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Increasing public awareness and concern over air pollution, strengthened by the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal book, Silent Spring, in 1962, prompted the US Congress to enact the Clean Air Act of 1963. The 1963 act sought to “improve, strengthen, and accelerate programs for the prevention and abatement of air pollution” and laid the foundation for the Air Quality Act of 1967, the Clean Air Act of 1970, and the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 and 1990. In Mexico, 324 days of dangerously high ozone levels in Mexico City in 1995 marked the initiation of a five-year National Environmental Program (1996–2000) to clean up air pollution. The Mexican government also passed a tax incentive program to encourage the purchasing of pollution control equipment. Older cars were gradually phased out between 2000 and 2006. In China, the 11th (2006–10) and 12th (2011–15) five-year plans (FYPs) reflect a similar resolve to mitigate air pollution. Further signals that the country is determined to fight air pollution include former president Hu Jintao’s vision of “scientific development” (2003) and “harmonious society” (2004), the 18th Party Congress’s vision of a “beautiful China” through the construction of “ecological civilization” (2012), and Premier Li Keqiang’s declaration of a “war on air pollution” at the annual meeting of the parliament (2014).

Despite these high-powered national directives to protect the environment, the degree of success varies greatly, even in the same location across time. When and why does environmental policy implementation fail? This is a two-part question. First, why has pollution sometimes continued to be a problem – a crisis, even – despite the national/federal governments’ efforts to make the attainment of high environmental standards a top priority? This question embodies both natural and social sciences dimensions. So far, social and political scientists have written prolifically on why some countries, particularly those with a strong political will in the capital and some of the world’s most comprehensive environmental regulations, may still fail to contain pollution in localities. For instance, in the United States, environmental policies can be diluted due to the lobbying of industry interest groups, political inaction, and lukewarm support from voters (Reference Heyes and DijkstraHeyes and Dijkstra 2001; Reference Oates, Portney, Mäler and VincentOates and Portney 2003; Reference List and SturmList and Sturm 2006; Reference CrensonCrenson 1971). In Mexico, short-tenure terms and the decades-long ban on reelection are viewed as impediments to the development of long-term municipal environmental plans and programs (OECD 2013).Footnote 1 Low priority on the legislative agenda and lobbying are other causes (Reference Ramos GarcíaRamos García 2011; Reference Jáuregui Nolen, Tello Medina and del Pilar Rivas GarcíaJáuregui Nolen, Tello Medina, and Pilar Rivas García 2012). In China, existing studies have pointed to the marginal status of environmental policies compared to economic ones, short-sighted environmental planning, ineffective environmental monitoring, and local protectionism to explain sloppy environmental policy implementation by local leaders (Reference Sinkule and OrtolanoSinkule and Ortolano 1995; Reference ShapiroShapiro 2001; Reference EconomyEconomy 2004).

However, the question of when has mostly been ignored. While theories may account for the static existence of pollution or the effect of ad hoc implementation campaigns on pollution reduction, they do not explain the systematic temporal variation in environmental policy implementation. Instead, nearly all existing works assume that after controlling for institutional factors and exogenous shocks like top-down campaigns, environmental policy implementation is constant over time. One possible explanation for this gap is the lack of comprehensive and fine-grained air pollution data that would reveal the variation in the effectiveness of policy implementation over time.

To address these shortcomings and fill this important gap, I utilize advanced pollution data that have only recently become available to uncover how local political incentives shape the implementation of air pollution control policies in a systematic way over time. Using this data, I illuminate the role of local political incentives in forging systematic local regulatory waves, as the top local politicians or political leaders prioritize different policies across their tenure to augment their chances of career advancement or reelection.Footnote 2

I theorize that local political tenures influence regulatory activities systematically. Strategizing local leaders or politicians are incentivized to cater to the policy preferences of their superiors (in autocracies) or constituencies (in democracies), giving rise to changing policy prioritization and, by extension, regulatory stringency during their tenure, creating what I call a “political regulation wave.”Footnote 3 For an air pollutant without binding reduction targets that determine career advancement, top local leaders or politicians are incentivized to gradually order laxer regulation of pollution to promote employment, social stability, and (reported) economic growth; thereby what I call a “political pollution wave” is generated. For an air pollutant with binding reduction targets, local politicians or leaders are incentivized to promote a stricter, more Weberian regulatory pattern.

However, the effectiveness of regulation efforts, and, by extension, the pattern in actual pollution levels would also vary based on the variability of the sources of the pollutant and the complexity of its formation. When the sources are limited and easy to target, and the formation process is relatively simple, the level of regulatory ambiguity is low; more consistent regulation leads to an observably more consistent level of pollution; thereby what I call a “political environmental protection wave” is generated. When the pollutant has many sources spanning several sectors and its formation processes are complex, regulation becomes ambiguous; the political pollution waves may persist.

Using observational data, remote sensing, box modeling, pollution transport matrices, official policies and internal documents, field interviews, and online ethnography, I find supporting evidence regarding sulfur dioxide (SO2) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution control in China.Footnote 4 I show that while dirty economic growth may explain why pollution exists, regulatory relief (or pressure) ordered by career-minded local leaders explains the systematic variation in air quality over time. The political regulation wave can deliver social benefits, but it may also impose insurmountable social costs. This book raises new questions about local governance and political accountability in autocracies and democracies alike.

Studying air pollution control provides a fascinating opportunity to understand the effect of political tenure on policy implementation. First, air pollution is the only type of pollution that researchers can measure systematically on a large geographic scale by using satellite instruments. Official sources of data can be sporadic and dubious, though they also provide important information about how local politicians or political leaders want to be perceived by their voters or superiors. Second, unlike other types of pollution (e.g., water pollution), for which there could be a significant time lag between the polluting activities and when their negative externalities manifest, air pollution happens concomitantly with emissions activities and stops when such events come to a halt. Third, but not least, studying air pollution carries tremendous normative significance. It is a driving cause of unnatural mortality and morbidity in places where most of the world’s population lives.

This book examines China as the primary case study because, although it has some of the world’s worst air pollution, its local patterns and causes are still not well understood. This pressing issue led Premier Li Keqiang to promise at a meeting in March 2017 that he would “reward heavily” anyone who could tackle the causes of smog (People’s Daily 2017).

Now that everyone is already well-fed and hopes to live well. That would require quality not only for eating and drinking but also for breathing. I have expressed several times at the executive meetings of the State Council. If there is a research team that can thoroughly uncover the formation mechanism and the hazards of smog and put forward more effective countermeasures, we are willing to reward heavily from the premier’s reserve fund! This is a top priority for people’s livelihood. We will not hesitate to spend money, and we must study the matter thoroughly!

Furthermore, much less is known about the effect of political tenures on public goods provision in authoritarian regimes.Footnote 5 With the use of high-quality and newly available data, studying the temporal patterns of local air pollution in China from a political science perspective can reveal new and interesting trends of policy implementation in an authoritarian context. Finally, the core argument centers on how changes in incentives alter political behavior as it pertains to environmental policy implementation. This makes China an excellent testing ground because there were changes in policy prioritization for two major and particularly harmful air pollutants in 2005 and 2012.

While the main empirical case is about air pollution regulation in China, the theory developed in this book can be applied to other countries and policy domains under scope conditions. Similar patterns are likely observed in contexts with the following attributes:

1. Local politicians or leaders can exercise discretion in policymaking and implementation within their jurisdiction.

2. They are incentivized to prioritize different policies at different times while in office.

3. The implementation of the policy involves a high level of conflict and a low level of ambiguity.

I will elaborate on those points in Chapter 2. In the last chapter, I provide evidence of systematic patterns of pollution in Mexico’s municipalities, tracking the tenures of state governors who possess significant power over the regulation of polluters. Future research could apply the theoretical framework in this book to study more empirical cases in a broad range of geographies and policy areas other than environmental governance.

1.3 Existing Explanations for Pollution Patterns and Their Limitations

Problems of implementation have been at the core of political science and public policy research for at least the past three decades. Implementation problems are amplified not only by the number of actors and the relationships between them but also by the actors’ decisions and veto points (Reference Pressman and WildavskyPressman and Wildavsky 1973; Reference Mazmanian and SabatierMazmanian and Sabatier 1981). These issues are further complicated by the degree of ambiguity of the policy goals, the degree of conflicts of interest, and the coping behavior of street-level bureaucrats (Reference MatlandMatland 1995; Reference LipskyLipsky 1980).

In the environmental realm, existing works have posited three principal arguments. First, local politicians or leaders sacrifice the environment on the altar of the economy to please their constituencies or political superiors. The center’s goals or expectations for the environment are at least sometimes sidelined by local leaders who perceive economic growth to be more critical, visible, and measurable. Second, short-sighted environmental planning is carried out to support growth and other policy goals whose effects can manifest swiftly enough for the leaders to claim credit and impress their superiors or voters. Last but not least, owing to information asymmetry where local leaders or politicians have the upper hand, local leaders can and do weaken environmental enforcement and monitoring without alerting the center or upsetting their constituencies. The following three subsections elaborate on these three points, first generally and then more specifically as they play out in China.

1.3.1 The Economy, Stupid!

Scholars have theorized and documented the impact of electoral and partisan incentives on economic policymaking extensively (Reference KeyKey 1966; Reference TufteTufte 1978; Reference NordhausNordhaus 1975). The overarching claim is that, given voters’ propensity to support candidates who are expected to deliver greater economic well-being, incumbents seeking reelection harbor powerful incentives to improve voters’ economic fortunes, or at least signal or feign such capability. This results in cycles of economic expansion and contraction that follow electoral cycles to win votes from myopic voters. Office holders seeking reelection usually prefer policies that are more targetable and timeable, manipulable, and attributable to themselves, as well as palpable to voters (Reference FranzeseFranzese 2002). That means that income growth and visible infrastructure projects bode well for electoral success (Reference TufteTufte 1978; Reference Achen and BartelsAchen and Bartels 2016), but they often require processes that generate copious amounts of pollution. In authoritarian regimes, the desire for promotion may induce similar incentives to boost the economy. For instance, scholars have argued that the ability to grow the local economy and generate revenue sits at the core of local cadre evaluation, a criterion that inadvertently leads to tremendous amounts of pollution (Reference LandryLandry 2008; L.-A. Reference ZhouZhou 2007; Reference JiaJia 2012; Reference Kahn and ZhengKahn and Zheng 2016).

The existing literature assumes that economic growth translates directly into pollution, so pollution is a multiple of economic outputs. Two implications ensue, depending on whether tenure length is fixed. If the terms are fixed, and peak growth can be timed accurately, peaks and troughs in pollution are likely the results of economic growth. On the other hand, if the tenure duration is flexible, efforts to promote economic growth should be continuously strong, leading to pollution levels that stay constant during tenure. I question this assumption and contend that development does not constitute the only pathway to pollution and that political regulation, rather than growth, could explain systematic pollution patterns.

1.3.2 Unsustainable Environmental Planning

The second stream of literature centers on environmental planning. Unsustainable environmental planning is the most prevalent when tenures are brief and incumbents can get away with short-sighted environmental performance upon leaving office. This is an example of a long-standing stream of literature on the time horizon of leadership and policy implementation (Reference OlsonOlson 1993; Reference Ferraz and FinanFerraz and Finan 2011).

In China, having a short tenure has been particularly at odds with sustainable, long-term environmental planning. Under pressure to demonstrate performance, local cadres are not incentivized to focus on the long-term welfare of their localities, nor to take on the difficult task of pursuing a sustainable and environmentally friendly path, since the effects of such policies only manifest in the long run (Reference Zhou, Lian, Ortolano and Ye.Zhou et al. 2013; Reference Eaton and KostkaEaton and Kostka 2014). During the policy implementation phase, local cadres who want to demonstrate their competency for promotion usually take on highly visible projects to showcase economic prosperity, such as massive construction of infrastructure and housing, which are also deliverable during their short tenures (Reference CaiCai 2004; Reference Wu, Deng, Huang, Morck and YeungWu et al. 2013).

Existing works assume that if environmental planning is unsustainable during a limited time horizon, it is always so. However, whether it is possible that environmental planning is sustainable at some points in time and unsustainable at others remains an open question.

1.3.3 Police Patrols Undermined

Finally, environmental enforcement and monitoring – the “police patrol” approach – are crucial for ensuring compliance with environmental policies. In China, poor environmental policy implementation has often been seen as a consequence of weak capacity. The lack of funding creates perverse incentives for local Environmental Protection Bureaus (EPBs), the main bodies in charge of implementing environmental policies, to allow industries to keep polluting because the pollution levies would indirectly contribute to the local EPBs’ budget.Footnote 6 Furthermore, a lack of capacity is often driven by a shortage of staff (Reference SchwartzSchwartz 2003).

Additionally, police patrols can also fail when the regulatory bureaucracy experiences capture. Regulatory enforcement can often fall short when the regulators tasked with enforcement have conflicting interests. When those interests are so deep that they prevent any serious enforcement – what is often called “regulatory capture” – it can seem as if the regulations were never written in the first place.

This was particularly evident in the Chinese context, where the interest to promote economic development had been at odds with the desire to protect the environment. The local EPBs were, until very recently, both administratively and financially dependent on the local government. The EPBs at each level were under the dual jurisdiction of the level immediately above them in the environmental protection system (tiao, or vertical) and the local government of the same administrative level (kuai, or horizontal) (Reference Lieberthal and OksenbergLieberthal and Oksenberg 1988; Reference MerthaMertha 2005). The dependence of local EPBs on local governments has been documented extensively in the environmental realm (Reference Sinkule and OrtolanoSinkule and Ortolano 1995; Reference Ma and OrtolanoMa and Ortolano 2000; Reference van Rooijvan Rooij 2003). As a result, the local EPB answered to the local leadership’s policy prioritization, which preferred stability and growth over the environment until 2010, around which time the status of environmental protection became significantly augmented.

Monitoring has proved very difficult at the local level due to a variety of ambiguities regarding policy means. In China, local EPBs and governments can juke the stats by tampering with pollution monitors or exploiting loopholes in the measurement requirement. However, while the existing literature assumes police patrol effectiveness is a constant, is it always undermined? If not, what is the pattern?Footnote 7

1.4 Toward A Generalizable Theory

The existing literature, as rich and informative as it is, makes one major assumption –after controlling for institutional factors and macro trends, air quality should be consistent over time. Is that true? If not, what does the air quality pattern actually look like? I find that there is systematic variation in the levels of pollution over time, independent of weather, climate, and seasonal factors, and that such variation is explained by the political calendars of career-minded local leaders. Hence, this book may both ask and answer the question: what explains the systematic variation in air quality over time?

This book takes a different view than the existing literature regarding the factors that explain reported changes in air quality. Extant works focus either on the manipulation of air quality data by subnational officials or on the effect of ad hoc, top-down implementation campaigns on actual air quality. For instance, many existing works about China focus on the manipulation of air quality statistics, such as with regard to the annual number of “blue sky days” – days when the recorded air pollution index (API) scores 100 or less.Footnote 8 Researchers have found evidence indicative of manipulation at the municipal level to achieve the Blue Sky Day policy goal, and suspicious data reporting most likely occurs on days when the deviation of the reported statistic from the real reading is least detectable (Reference AndrewsAndrews 2008a; Reference Ghanem and ZhangGhanem and Zhang 2014). Nevertheless, is reaching Blue Sky Day goals really what some authors call “effortless perfection” that required merely data manipulation? Have there been actual efforts on the ground that led to real changes in air quality?

The few works in this line of research study the effects of ad hoc, campaign-style regulation to reach specific goals, such as having blue skies during special events (e.g., Olympic Blue, the APEC Blue, the Parade Blue) and achieving quick air quality results while under intense scrutiny (e.g., heavy-handed regulation during China’s recent War on Air Pollution). These events are usually exploited as exogenous shocks to study changes in air pollution and their subsequent health effects (Reference Wang, Hao, McElroy, Munger, Ma, Chen and NielsenWang et al. 2009; Reference Lin, Liu, Fang, Xiao, Zeng, Li and GuoLin et al. 2017; Reference Meng, Zhao, Sun, Zhang, Huang and YangMeng et al. 2015; Reference Cermak and KnuttiCermak and Knutti 2009).

Departing from these works, this book dives into explaining the systematic variation in actual and reported air quality over time after controlling for the effects of top-down campaigns. In both democracies and autocracies, local leaders or politicians face incentives to deliver achievements when considered for reelection or promotion. These achievements could be related to economic development, public infrastructure, revenue generation, social stability, clean air, among others. Some of these goals can be contradictory (e.g., economy and employment vs. environment), which requires strategically prioritizing some goals over the others for career gains. Based on new research, I argue that local political tenure can be a crucial determinant of air quality. Taking a step back, the following chapter will elaborate on the scope conditions of the general theory of the political regulation wave, which could be applied to study how the political tenure influences air quality.

1.5 Methods of Inquiry

In recent decades, two quasi-natural experiments emerged in China in 2006 and 2013, respectively. The country experienced a shift in policy prioritization – from the economy and stability to ecology and the environment. This delivered a unique opportunity to test my theory of the political regulation wave. I pursue a mixed-methods approach that integrates qualitative and quantitative inquiries organically. My qualitative methods of investigation include: (1) field interviews, (2) online ethnography, and (3) research on news articles, reports, and public and internal policy documents. My quantitative approaches consist of: (1) remote sensing, (2) box modeling, and (3) regression analysis based on data from prefectural yearbooks, online government databases, and satellite-derived statistics. This research is approved by the institutional review board at Stanford University (IRB-33872).

1.5.1 Qualitative Research

I draw qualitative information from more than 100 semistructured interviews over nine months of fieldwork in five provinces (the coastal provinces of Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, and Zhejiang as well as the inland province of Sichuan) and Beijing, three years of online ethnographic research, and very elaborate and extensive research on central and local news articles, reports, and internal policy documents in Chinese.Footnote 9 My research assistants and I built the top prefectural leadership dataset based on information from prefectural yearbooks housed at local libraries and archives and online government databases. I explain each approach in more detail below.

Field Interviews

I employed a snowball sampling technique to conduct in-person interviews with officials who worked for the local government and the EPBs, chief officials and engineers in central environmental planning, factory managers, university professors who teach environmental science and policy, and leading scholars and experts on political promotion in China. On average, an interview trip at the interviewees’ workplace lasted three hours. About half of the interviewees went overboard in aiding my research by making themselves available for follow-up in-person meetings and phone calls. All interviews were conducted in confidentiality, and the names of the interviewees are withheld by mutual agreement. To further ensure confidentiality, interviews conducted with multiple individuals working at the same workplace are assigned one shared interview number.Footnote 10

Online Ethnography

To double-check the information from interviewees, I also employed an online ethnographic approach. Extant works that utilize the online ethnographic approach follow online forums (Reference YangYang 2003; Reference HanHan 2015). Instead, I opted for a more private setting that likely had a much higher concentration of insiders – small- to medium-sized and invitation-only WeChat groups.Footnote 11 Each of these WeChat groups comprised anywhere between 100 and 500 members, including local officials in charge of environmental work, university scholars, central officials and advisors, and industrial leaders. Each member must use their real name and work affiliation or risk removal from the group, so the probability of fake posts is very low. It arguably provided the most up-to-date and trustworthy interactive discussion on central and local politics and policy about China’s environment. I followed these discussions closely. The conversations concerning implementation challenges were particularly informative and enlightening.

News Articles, Reports, and Internal Policy Documents

My third source of qualitative information consisted of news articles (mostly from central and local publishers), reports, internal policy documents collected during fieldwork, and other policy documents from central and local government websites. I referenced primarily Chinese-language sources, many of which were exceptionally rich and detailed but were rarely picked up by English-language media. Some examples of these include the National Business Daily (每经网), the Economic Observer (经济观察网), and China Business (中国经营网).

Top Local Leadership Biographic Dataset

To build the Chinese top prefectural leadership dataset, I made several trips to local libraries and archives in places I conducted fieldwork to survey and collect information from prefectural yearbooks. I later discovered two official websites (www.people.com.cn and www.xinhuanet.com) that hosted most of such information. Thereafter, I hired an army of undergraduate research assistants to assist with collecting the rest of the dataset. The information gathered included leaders’ names, tenure start and end dates, birth year, hometown, ethnicity, educational level, educational background (e.g., name of college attended and major), and training at the Central Party School. The name and tenure start and end dates were almost always available. Information about the other variables was not always comprehensive.

1.5.2 Quantitative Research

On the quantitative side, I utilize air pollution data generated from a combination of remote sensing and atmospheric modeling, which became available thanks to recent advancements in both fields. I employ a box model to explain cross-jurisdictional pollution spillover effects in China. I run statistical analyses to understand the relationships between key temporal explanatory variables and pollution outcomes, which, combined with qualitative evidence, uncover the causal mechanisms behind such relationships.

Remote Sensing and Atmospheric Modeling

This book improves on previous works that sought objective measures of air pollution in China. Instead of relying on questionable official data, point estimates, or simple use of aerosol optical depth (AOD), I employ high-resolution, ground-level estimates for pollution measures derived from three satellite instruments: the moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS), the multi-angle imaging spectroradiometer (MISR), and the sea-viewing wide field-of-view sensor (SeaWiFS).Footnote 12 Each linked total column AOD retrievals to near-ground PM2.5 via the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model (GEOS is the abbreviation for Goddard Earth Observing System). Thus far, official data published in yearbooks, statistics from self-reported industrial surveys, and figures from official websites have been commonly used in works on air pollution in China (Reference HeHe 2006; Reference Chen, Ebenstein, Greenstone and Li.Chen, Ebenstein, et al. 2013; Reference Zheng and KahnZheng and Kahn 2013; Reference Zheng, Kahn, Sun and LuoZheng et al. 2014; Reference Tian, Guo, Han and AhmadTian et al. 2016). I will also reference officially reported statistics in my analysis because they reflect what localities want the upper levels to believe. Some works made some progress in seeking more objective measures of air pollution such as air pollution monitor readings at the US Embassy in Beijing (Reference WangAlkon and Wang 2018). Still, point measurements collected in the backyard of the embassy are not representative of regional concentration. As a further yet still imperfect improvement, some works made use of AOD as a proxy for air pollution (Reference Chen, Jin, Kumar and ShiChen, Jin, et al. 2013). However, the direct application of AOD does not take into account meteorological factors and systematic temporal and spatial variability that transforms the relationship between AOD and PM2.5 (Reference Paciorek and LiuPaciorek and Liu 2009). The applicability of AOD as a valid measure of surface air quality hinges upon several factors – including the vertical structure, composition, size distribution, and water content of atmospheric aerosol – which are impacted by changes in meteorology and emissions (Reference van Donkelaar, Martin, Brauer, Kahn, Levy, Verduzco and Villeneuvevan Donkelaar et al. 2010). Van Donkelaar and collaborators, whose methodology and shapefiles are used for this book, improved on these fronts by combining three PM2.5 sources from MODIS, MISR, and SeaWiFS satellite instruments and estimating at a spatial resolution of around 10kx10km (Reference van Donkelaar, Martin, Brauer and Boysvan Donkelaar et al. 2015; Reference van Donkelaar, Martin, Li and Burnettvan Donkelaar et al. 2019).Footnote 13

Box Modeling

To account for pollution spillover effects, I use a box model – which is commonly used in engineering fields to represent the functional relationships between system inputs and system outputs – to explain how, despite flows in and out of a given jurisdiction, the estimated statistical significance of the political regulation wave is robust against wind spillover effects. However, the magnitude of the impact is likely attenuated.

Statistical Analyses

I employ ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis to understand the temporal effect of local politicians’ or leaders’ tenures on environmental and economic outcomes. I complement OLS regressions with a causal mediation analysis to increase the confidence with which I adjudicate different causal mechanisms.

1.6 Intended Audiences and Scholarly Contributions

While grounded primarily in political science, the book is presented to pique the interest of public policy scholars, policymakers, environmental scientists and engineers, journalists, and the media, in addition to political scientists. It finds company with works on federalism and decentralization, local politics, governance, public goods provision, the unintended consequences of public policy, political control of the bureaucracy, policymaking and implementation in authoritarian contexts, environmental politics and policy, political challenges to advancing technological change, interdisciplinary approach to tackle pressing societal challenges, among others. Section 1.7 will delineate this book’s policy relevance and suggest practical solutions for problems in which policymakers and engineers have a particular interest.

This book seeks to make three principal contributions in theoretical, empirical, and normative terms. Theoretically, it introduces a new driver of local policy waves – local political incentives can shape actual policy implementation, not just reported statistics that are subject to manipulation, in plausibly predictive ways. Such an effect exists independently from top-down implementation campaigns.

The political regulation wave phenomenon suggests a situation where the preferences of political superiors and subordinates are aligned, contrary to the bulk of existing literature on Chinese politics that argue for a central-local agency dilemma.Footnote 14 The political superior uses heuristics tied to a political regulation wave to identify talent in control of their localities and to show a gradual improvement in key policy areas. The subordinate panders to the preferences of their superior by creating a political regulation wave.

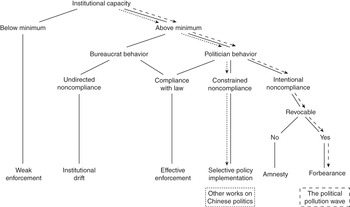

Empirically, the book sheds light on the systematic prioritization of different local policy goals throughout a top local leader’s tenure in an authoritarian country and, to a lesser extent, in a democratic one. In contrast to some existing claims about reasons behind environmental governance failures, this book suggests that even when there are sufficient resources and capacity to regulate, strategizing local leaders or politicians could opt for laxer regulation of pollution in exchange for greater political achievements aligned with central priorities or voter preferences. In other words, local political leaders or politicians fostered regulatory forbearance rather than selective policy implementation, the latter of which has been identified extensively as the culprit for poor policy implementation in China and elsewhere (Figure 1.1).Footnote 15

Figure 1.1 Comparison between selective policy implementation and forbearance

Normatively, the book posits that the institutions of political tenure and an evaluation scheme that values gradual improvement in achieving key policy goals (e.g., China) or peak performance at critical times (e.g., Mexico) may result in unintended consequences. Such consequences, such as tremendous human costs and welfare losses, pose challenging questions about tradeoffs for decision-makers. With real-world, life-and-death impacts, this normative dimension speaks to the additional value of theorizing and empirically examining the political regulation wave phenomenon.

The major empirical part of the book studies most areas in China and compares them rather than following the trend among recent works in Chinese politics to explore only specific regions. Exploring a newly discovered and documented phenomenon that applies to a wide range of geographic regions can boost the appeal of the theory and the empirical analysis.

To bolster the comparative angle of the project, I posit that the political regulation wave theory likely explains local political behavior and policy implementation in decentralized political systems across democratic and authoritarian regimes under scope conditions. Local politicians or leaders have considerable decision-making power and control over resources. In Section 7.1 on external validity, I apply the theory of the political regulation wave to explain peak pollution in gubernatorial election years in Mexican municipalities. The existence of political pollution waves in both China and Mexico suggest that democracies and autocracies may not be that different in providing one critical type of public good – air quality. This finding stands out as one of a few outliers vis-à-vis a long stream of established theoretical and empirical works, which argue that democracies are better than autocracies at providing public goods consistently.

Another distinguishing feature of the book is its innovative blending of data and techniques from political science, earth systems sciences, and environmental engineering. Leveraging my training as both a political scientist and an environmental engineer, I present, to my knowledge, the first book that integrates techniques such as remote sensing, box models, and pollution transport matrices with empirical research grounded primarily in political science. The book introduces new areas for interdisciplinary environmental dialogue, which would illuminate promising new solutions to pressing environmental challenges of our times.

1.7 Policy Relevance

As mentioned earlier, air pollution is a silent and invisible killer more lethal than violence, diseases, and smoking. In addition, breathing polluted air makes one more vulnerable to dying from infection with COVID-19. Understanding the determinants for effective air pollution regulation is both critical and timely. This book offers the concept of a political regulation wave, as well as substantive empirical evidence. While China is the primary case study in this book, the idea can be widely applicable to other decentralized political systems where local political incentives can influence bureaucratic regulatory activities.

The new results are timely for air pollution management in China and beyond. China declared a “war on air pollution” in 2014 and poured tremendous amounts of resources and efforts into containing PM2.5 pollution, including enhancing local monitoring and adjusting the incentive structure for local officials to regulate PM2.5 more and more aggressively over time. However, the political pollution waves, where pollution gradually increased across the top local leader’s tenure, persisted. In the winter months of 2021, major haze pollution incidents haunted China’s central-eastern region despite heavily reduced industrial activities and automobile emissions amid the COVID-19 pandemic. This book unveils the rationale and mechanism behind the political regulation wave, which could help spark additional critical conversations in the policy community on finding meaningful ways to manage a complex pollutant’s concentration effectively.

Additionally, the book challenges the conventional wisdom that having the right incentives and enhanced monitoring is critical to successful policy implementation. The new results reported in the book suggest that understanding an air pollutant’s particular characteristics and how political factors influence its emissions are just as important. The book recommends collaboration between political stakeholders and atmospheric modelers. Atmospheric modelers could help better identify the sources of PM2.5 for each locality, which could aid local leaders in ordering regulation of targeted sectors at the right time, thus preventing future pollution waves.

1.8 Roadmap for the Book

This book’s backbone is a theoretical, empirical, and normative exploration of incentives: how they shape political and bureaucratic behavior, as well as their unintended environmental and social consequences. Specifically, this book explores the systematic conditions under which implementation of the more significant policy goals from the perspective of top local leaders entails sacrifices of the less important. It is worth noting that the book does not seek to suggest that incentives are the sole explanation of political behavior; rather, incentives are a vital force that shapes behavior.

The book’s findings suggest that local leaders in China are highly responsive to the center’s policy preferences, as evidenced by their own policy prioritization through their tenure. Hence, unlike many existing works on central-local relations in China, this book does not employ the principal-agent framework because it assumes a mismatch in interests between the principal and the agent, contrary to the major findings in this book.

The question of political selection yields more significant normative implications in authoritarian regimes, such as with regard to the degree of social welfare. Leaders face fewer constraints and wield more political power than their counterparts in democracies (Reference Hodler and RaschkyHodler and Raschky 2014). Hence, China is a valuable case to study. The quasi-natural experiments in China before and after 2005 and 2010 make it possible to apply the two sides of my theory of the political regulation wave.

The book progresses through three sections. The first section (Chapters 1–3) rolls out background information and the political regulation wave theory. The second section (Chapters 4 and 5) applies the theory to examine empirical evidence from Chinese prefectures. It further delves into the factors that influence the strength of the political regulation wave by answering the question: who creates the political regulation wave? The third section (Chapters 6 and 7) uncovers the hard tradeoffs the political regulation wave entails, and discusses implications of the findings.

What are the theoretical underpinnings that account for the systematic variation in air quality over time? Before addressing this specific puzzle, I take a step back in the first part of the book and situate the case of air pollution regulation within the broad framework of policy implementation. I then delineate the microfoundations of environmental governance in China. In Chapter 2, I put forth a general theory to explain systematic local policy waves undergirded by local political incentives. I outline the three foundational blocks of the theory of the political regulation wave, which draws upon and advances three main streams of literature in political science and public policy: (1) the political origins of local policy waves, (2) incentives and political behavior, and (3) leadership time horizon and policy implementation. It is aimed at being a general theory with scope conditions. Then I explain why the regulation of air pollution in China makes a compelling case to test the theory. The chapter ends with testable empirical implications for air pollution control in China.

Chapter 3, “Local Governance in China,” explains the background and evolution of environmental governance in China, from the 1980s to the present. It introduces readers to the fundamental concepts of central-local relations, how localities are governed, and their implications for environmental protection. While most environmental institutions remained consistent across four decades, new national priorities have emerged at different times. The environment was largely sacrificed for economic growth before 2000. Under the 11th FYP (2006–10), binding targets tied to local leaders’ promotion were introduced for SO2 and chemical oxygen demand (COD) control. After 2010, PM2.5 became monitored in four regional clusters. Under the first phase of the State Council issued Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan (大气污染防治行动计划) (2013–17) – known in short, as the Clean Air Action Plan – meeting PM2.5 pollution reduction targets became binding in select cities (State Council 2013a). Changed rules altered the incentive structure of local implementers. Furthermore, mechanisms to enhance monitoring – including public participation in monitoring – for different pollutants were put in place to improve implementation.

What empirical evidence is there for the theory of the political regulation wave? In the second part of the book (Chapters 4 and 5), I explore answers to this question based on evidence from two quasi-natural experiments, provided by the two policy shifts described above, for air pollution control. The regulation of SO2 and PM2.5 presents varying governance challenges, as PM2.5 travels far and is generated from various sources spanning many sectors while SO2 stays close to its source and is emitted primarily by the industrial sector. I follow a quantitative and qualitative mixed-methods approach, where I unveil statistical relationships between local tenures and pollution outcomes as well as between local tenures and economic indicators. I further illuminate causal mechanisms via both quantitative and qualitative evidence, which involves a causal mediation analysis, field interviews in representative cities, internal and publicly available official policy documents, and online ethnography.

Chapter 4, “The Case of Sulfur Dioxide Control,” exploits a policy initiative that made SO2 emissions reduction a binding target under the 11th FYP (2006–10), which altered the incentive structure of top local leaders. Both official and satellite-derived measures of the regulatory stringency of SO2 reveal patterns consistent with the political regulation wave theory. When the reduction targets were nonbinding, the regulation of SO2 became gradually relaxed under the 10th FYP (2001–5) without binding targets. When the targets became binding in cadre evaluation under the 11th FYP, a more regularized regulation of SO2 was observed. Such effects are strong among top local leaders in prefectures that received high reduction targets, possibly because higher targets were matched by more significant efforts to avoid negative attention from upper levels.

Chapter 5, “The Case of Fine Particulate Matter Control,” presents the second empirical case study, which takes advantage of a policy change under the first phase of the Clean Air Action Plan (2013–17). The plan mandated select cities to reduce PM2.5 pollution by designated percentages based on 2012 levels by 2017. Before 2010, when PM2.5 was not yet a criteria air pollutant, I find that top local leaders extended environmental regulatory forbearance in favor of more critical political goals such as maintaining stability and promoting (reported) economic growth. After 2012, cities continued to experience a gradual increase in pollution during a top leader’s tenure, ceteris paribus, regardless of whether they were under the action plan, though officially recorded statistics would reveal much-dampened pollution waves in treated prefectures – namely, prefectures under binding reduction mandates. In deriving these findings, I draw on findings from field interviews to explain how local leaders extended regulatory forbearance to polluting industries to achieve social stability at the expense of the environment. I use a causal mediation analysis to further corroborate environmental regulation as the dominant conduit to induce the political pollution wave. When leaders were not connected to their direct political superiors, political pollution waves were more pronounced.

In the third part of the book, I summarize the findings and discuss their theoretical and normative implications. I demonstrate the external validity of the theory based on evidence from municipalities in Mexico. Finally, I deliberate on the policy implications of the theory and the potential solutions it provides and point out future research directions.

Chapter 6, “The Tradeoffs of the Political Regulation Wave,” assesses the normative implications of the political regulation wave, as well as the hard tradeoffs it entails. I demonstrate, both via quantitative estimation and qualitative case descriptions, how the political regulation wave can deliver social benefits but also impose insurmountable social costs. Lax regulations benefit the economy and employment, but result in more pollution, which threatens human well-being – even leading to premature deaths. When regulation is strictly imposed, air quality improves, but many lose their jobs, profits, and welfare while spending brutal winters without heating, as local leaders use the beautiful blue skies to advance themselves up the political hierarchy. These are difficult tradeoffs.

Chapter 7 concludes the book. The results en masse suggest that local political incentives can shape policy prioritization across a leader’s tenure and be a potent source for systematic local policy waves. Such incentives influence the scale and intensity of regulatory activities, creating political regulation waves. These results challenge traditional notions of local implementation under nomenklatura control, which assumes that local compliance is constant. Beyond China, I argue and show, using Mexico as an example, that the political regulation wave theory applies to other countries under scope conditions. Additionally, these findings raise new questions about local governance and political accountability across both autocracies and democracies, and I use this chapter to explore them. The existence of the political regulation wave is an inconvenient truth, the solution to which would involve the right mix of incentives, independent monitoring, a delicate balance between allowing leeway and maintaining accountability at the local level, and collaboration between political stakeholders and atmospheric modelers.