Adolescence is a transition period between childhood and adulthood, characterised by a rapid rate of growth and development(1). Adolescents are particularly at risk of malnutrition due to the increased nutritional requirements to match the needs generated by developmental processes(Reference Das, Lassi and Hoodbhoy2). Although healthy eating patterns are essential to achieve optimal growth and development, a strong body of evidence shows that the unhealthy dietary habits in adolescence are a pivotal public health problem worldwide(Reference Aljaraedah, Takruri and Tayyem3).

Globally, the eating habits of adolescents have been reported to be characterised by an insufficient intake of vegetables and fruits and a high consumption of ultra-processed products with excessive content of sugar, fat and Na, such as sugar sweetened beverages and fast foods(Reference Aljaraedah, Takruri and Tayyem3,Reference Christian and Smith4) . This leads to an inadequate intake of micronutrients, such as vitamins, Ca, K and Zn, and an intake of free sugars, saturated fat and Na that exceeds nutritional recommendations(Reference Aljaraedah, Takruri and Tayyem3,Reference Appannah, Pot and Huang5) . Associated with these dietary patterns, overweight and obesity among adolescents have markedly grown worldwide, which increases the risk of premature mortality and non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, hypertension and type 2 diabetes(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli6–8). In addition, obesity during childhood and adolescence has been associated with deleterious consequences on brain development and psychosocial burden, including stigma, depression, hyperactivity disorder and attention deficit(Reference Wang, Freire and Knable9–Reference Lowe, Morgon and Reichlet11).

In this context, the implementation of policies to encourage healthier eating habits among adolescents have been identified as a priority for policy making(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli6). Such policies can lead to immediate health benefits and contribute to the establishment of healthy habits that reduce likelihood of morbidity, disability and premature death in adulthood(1). According to the developmental origins of health and disease, an improvement in the eating habits of adolescents can have a positive impact on their life course health and well-being, as well as on the health of their offspring(Reference Gluckman, Hanson, Gluckman and Hanson12).

The eating habits of adolescents are determined by the complex interaction of individual characteristics, such as physiological, psychological and cognitive factors, as well with the characteristics of the food system(Reference Stok, Hoffmann and Volkert13–Reference Raza, Fox and Morris15). In particular, interpersonal/social (i.e. the interactions of adolescents with peers, parents, siblings, etc.) and environmental factors (i.e. the characteristics of the environment were adolescents live and procure food) have been increasingly recognised as key drivers of adolescents’ diets(Reference Fox and Timmer14,Reference Raza, Fox and Morris15) . This suggests that multifaceted strategies addressing the food environment, the food system and behaviour change communication are needed to trigger changes in the eating habits of adolescents(Reference Hawkes, Jewel and Allen16,Reference Jonsson, Larsson and Berg17) .

Adolescence is a period of learning, increased independence from parents and adjustments in preferences, personal goals and motivations(18,Reference Crone and Dahl19) . The way adolescents make their food choices are expected to differ from those of adults, as they are more influenced by reward, excitement and social pressure(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli6,Reference Crone and Dahl19) . Therefore, an in-depth understanding of the views of adolescents can provide new insights on the barriers and enablers to healthy eating and contribute to the development of more effective policies(Reference Spencer20,Reference Ballard and Syme21) . The active engagement of adolescents in the development of collaborative prevention programmes can lead to positive development benefits, increased critical awareness and self-efficacy(Reference Ballard and Syme21). In this sense, behavioural interventions are likely to fail if they are not aligned with adolescents’ needs(Reference Yeager, Dahl and Dweck22). Adolescents are curious and innovative and can contribute to accelerate progress, as has been previously reported for policies developed using co-creation(Reference Kleinert and Horton23,Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers24) . This approach is aligned with the perspective of children’s rights, which emphasises that children and adolescents have the right to be heard, particularly in matters related to their health and well-being(25).

The present work aimed at informing the development of strategies to encourage healthy eating by qualitatively exploring the views of Latin American adolescents, which have been so far underrepresented in the literature(Reference Taylor, Garland and Sanchez-Fournier26,Reference Verstraeten, Van Royen and Ochoa-Avilés27) . Focus was placed on early adolescence. During this period, adolescents tend to show a low perceived susceptibility to health risk, a poor ability to self-regulate their impulses and to more frequently engage in risky behaviours compared with adults(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli6,18,Reference Crone and Dahl19) . In particular, the following objectives were sought: (i) to explore adolescents’ views about the foods they consume and (ii) to identify their ideas about strategies to encourage healthier eating habits.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted using a convenience sample of adolescents, recruited at two educational institutions with different socio-economic background in Montevideo and its metropolitan area (Uruguay). At each institution, adolescents aged between 11 and 15 years were invited to participate in the study. Informed consent forms were sent to parents. Only adolescents whose parents signed the informed consent form participated in the study. A total of 102 adolescents (aged between 11 and 15 years (Mean = 13·2, sd = 1·1), 52 % female) participated in the study.

Initially, the study was planned to be conducted with adolescents aged between 11 and 15 years in all the classes in the two institutions in order not to leave anyone out. After the analysis of the last group, no new topics emerged. This indicated that saturation was reached(Reference Carlsen and Glenton28), and therefore no additional data collection were deemed necessary.

Data collection

Adolescents completed the study in their own classroom during their school time. All the adolescents in the class whose parents had previously signed the informed consent completed the task at the same time, under the supervision of four researchers who moderated the activity composed of an individual and a group task. They provided their oral assent to participate in the study.

First, adolescents were asked to complete an individual task which consisted of four open-ended questions aimed at identifying their perceived need to change the type of foods they normally consumed. The wording of the questions was the following: (i) What foods that you know are bad for your health do you eat often?; (ii) Why do you eat them if you know they are not good for you?; (iii) What foods that you know are good for your health do you consume rarely? and (iv) Why don’t you eat them more often if you know they are good for you? For each question, they were provided with a 16 × 8 cm blank space in a paper ballot. They were also asked to indicate their age and gender. During the task, adolescents did not interact with each other, nor with the researchers.

Then, a group task was performed, guided by a researcher. All the adolescents in the class were divided in four groups of 6–8 participants. They were asked to think about how they could convince their friends to consume less foods bad for their health and more foods good for their health. They were provided with a A2 sheet of paper to write down their ideas. Each group worked with the assistance of a researcher, who motivated the group discussion.

Data analysis

Data were qualitatively analysed. The foods regarded as bad for health but frequently eaten and foods regarded as good for health but rarely eaten were translated from Spanish to English. Word clouds were used to obtain a graphical representation of the individual responses provided by participants, without any type of grouping or categorisation. In a world cloud, all the individual words mentioned by participants are represented as a weighted list where font size is proportional to the number of times that the word was mentioned by participants(Reference Jin29). Word clouds were obtained using the website wordart.com

Content analysis was used to analyse data from the open-ended questions and the group task due to its reliability, flexibility and data-driven nature(Reference Bengtsson30). Responses to the open-ended questions about reasons for frequently consuming foods bad for health and rarely consuming foods good for health were analysed based on inductive coding approach(Reference Krippendorff31). A data triangulation approach was used for coding the data. One of the researchers performed an initial coding by repeatedly examining the responses. Two additional researchers checked the coding and did not propose any modification. Examples of quotes for each category were selected and translated from Spanish to English for publication purposes.

Responses to the group task where participants were asked to propose strategies to promote healthy eating among adolescents were analysed using a deductive-inductive approach. The strategies written in the A2 sheets were grouped according to the domains and policy areas proposed in the NOURISHING framework developed by the World Cancer Research Fund International(Reference Stok, Hoffmann and Volkert13). Within each policy area, an inductive coding approach was used to identify any specific characteristic of the strategies detailed by participants. The analysis was performed using a data triangulation approach, as described in the previous paragraph.

Results

Adolescents’ views on foods regarded as good and bad for health

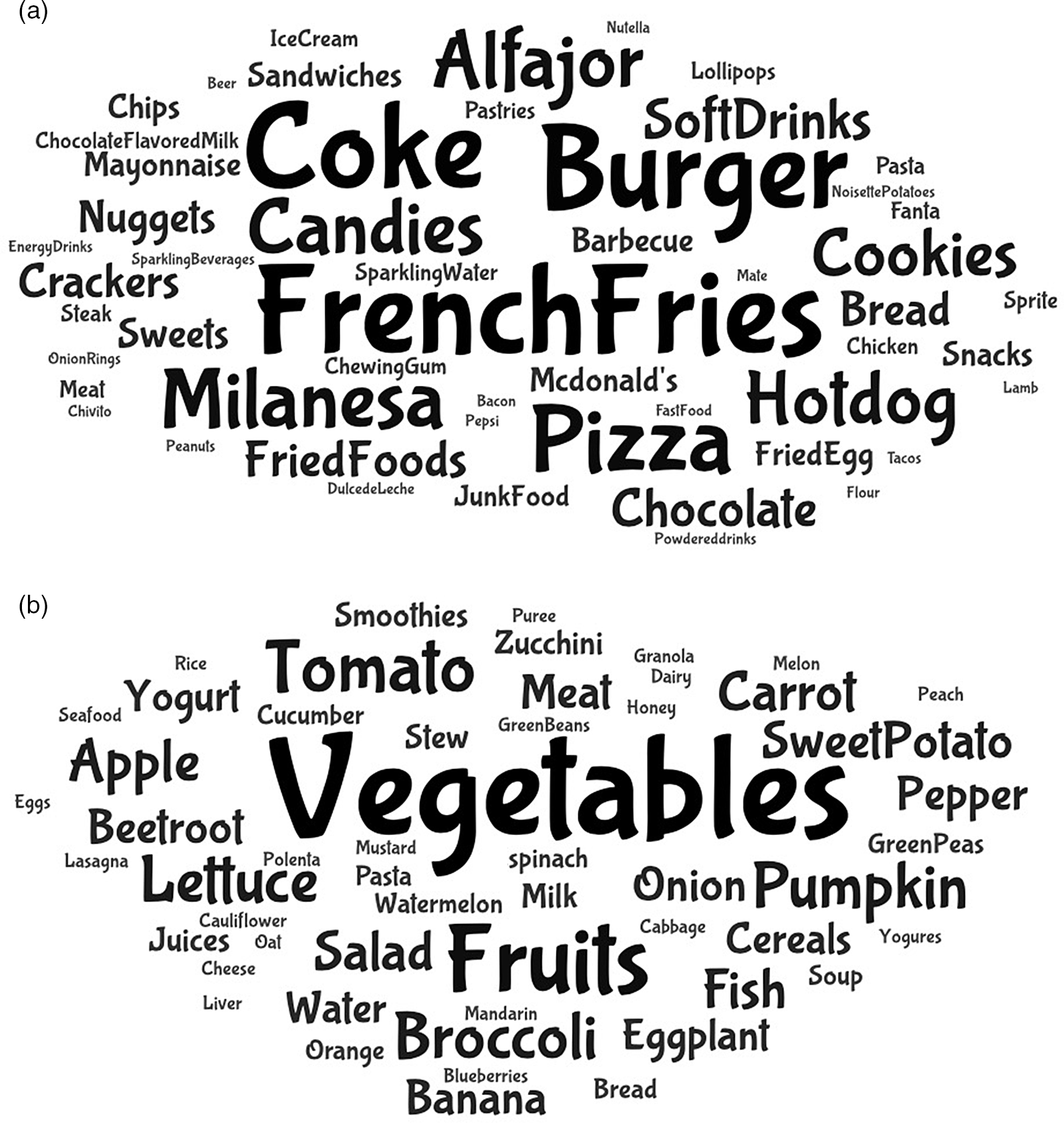

Adolescents identified a wide range of foods they frequently ate although they regarded them as bad for health (Fig. 1(a)). Most of the foods were ultra-processed products (e.g. soft drinks, burgers, candies, alfajor (a traditional product in Uruguay and other Latin American countries, composed of two cookies with a layer of dulce de leche (a traditional type of sweetened condensed milk), chocolate or other sweet spread, usually covered with chocolate or meringue), cookies) or fried foods (e.g. French fries, milanesa (a thin slice of meat, usually beef or chicken, dipped in egg and dredged in breadcrumbs, which is then pan-fried or, less frequently, baked)). Only few participants mentioned natural or processed foods (e.g. meat, bread). When asked about the reasons for consuming those foods, participants mentioned individual, interpersonal and environmental factors.

Fig. 1 Word clouds of the foods adolescents regarded as bad for health but frequently ate (a) and the foods they regarded as good for health but rarely ate. (b) The size of the words is proportional to their frequency of mention. Alfajor is a sweet cookie sandwich filled with a layer of dulce de leche; Dulce de leche is a traditional type of sweetened condensed milk; Milanesa is a breaded thin slice of meat or chicken usually fried (similar to schnitzel); Chivito is a traditional Uruguayan meat sandwich

Hedonics, i.e. the pleasure associated with food consumption, emerged as the most frequently mentioned factor. Most of the participants stated that they ate foods they regarded as bad for health because they liked them. Responses mainly referred to the sensory characteristics of the products and their associated pleasure (e.g. ‘I like how they taste’, ‘They are yummy’, ‘They are very tasty’, ‘Because their flavor attracts me’). As exemplified in quotes shown in Table 1, some of the participants regarded the products as addictive and stated that they usually found it hard to refrain from eating them or to control the quantity they eat.

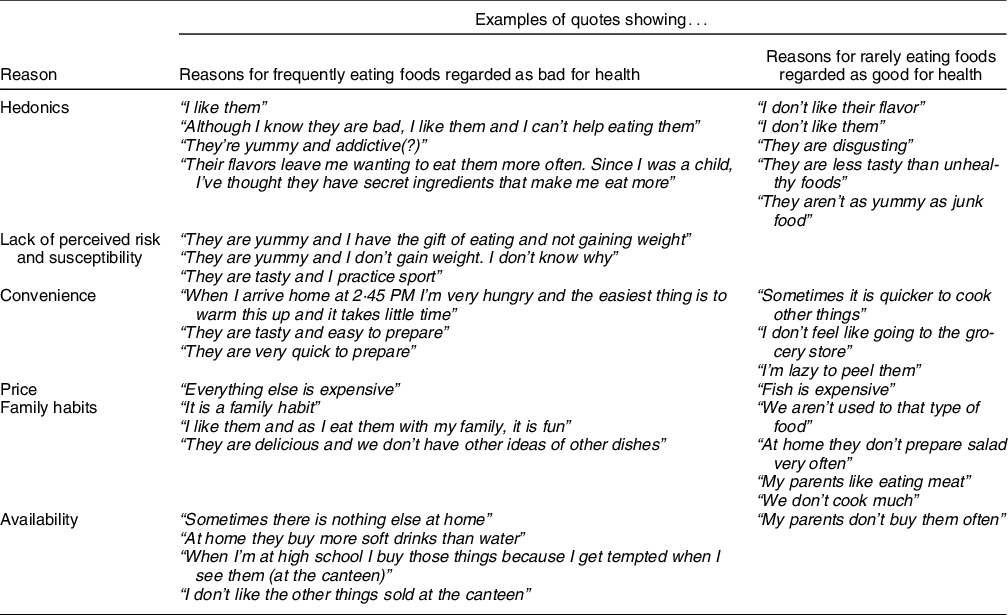

Table 1 Reasons mentioned by adolescents for frequently eating foods regarded as bad for health and rarely eating foods regarded as good for health

Another individual factor underlying consumption of foods regarded as bad for health was lack of perceived risk and susceptibility to their negative health consequences. As shown in Table 1, some of the participants thought that they were not susceptible to the negative health consequences of unhealthy foods because they did not gain weight or because negative effects were compensated by practicing sports. Participants also mentioned convenience-related factors as motivators for the consumption of foods regarded as bad for health, such as lack of time or willingness to minimise the time and effort invested in food preparation.

Adolescents identified a series of environmental factors as reasons for consuming foods bad for health. As shown in Table 1, participants referred to the low price of ultra-processed products and their high availability at home and the school canteen as motives underlying their frequent consumption. Furthermore, they regarded consumption of ultra-processed products as a family habit, i.e. something they frequently do. One of the participants described family consumption of ultra-processed products as fun (Table 1).

Regarding foods good for health that are rarely eaten, vegetables were by far the most frequent response, followed by fruits (Fig. 1(b)). The reasons for not consuming these foods were mostly related to dislike and disgust, followed by their lack of convenience. As shown in Table 1, adolescents referred to the foods good for health they rarely eat as disgusting, as well as less tasty and less yummy than unhealthy or junk food. In addition, fruits and vegetables were regarded as not convenient because they require peeling or longer cooking times. Price was also mentioned as the reason for the infrequent consumption of fish by one of the participants. Finally, adolescents mentioned lack of family habit and lack of availability of healthy foods at home as reasons underlying their infrequent consumption. As shown in Table 1, they stated that their parents do not frequently purchase or prepare healthy foods as a consequence of habits, preferences or lack of cooking skills.

Strategies to promote healthy eating among adolescents

In the group task, adolescents proposed strategies related to two of the domains of the NOURISHING framework: behaviour change communication and food environment (Fig. 2). Most of the proposals were related to the development of communication campaigns and interventions aimed at encouraging behaviour change.

Fig. 2 Strategies proposed by adolescents for reducing consumption of foods bad for health and increasing consumption of foods good for health, grouped according to the NOURISHING framework(Reference Stok, Hoffmann and Volkert13)

Social media was identified as a key channel of communication to target adolescents. However, other more traditional channels such as billboards and leaflets were also mentioned (Fig. 2). The participation of celebrities (e.g. singers, actors and football players) and social media influencers was highlighted as a key determinant of the efficacy of the campaigns. Some of the participants stressed that celebrities should speak directly at them using the vocabulary adolescents normally use. Video games, festivals and songs from famous singers were also mentioned as potential strategies to encourage adolescents to eat healthily.

Regarding the content of the communication campaigns, three main approaches were identified. The most frequently mentioned approach was raising awareness of the negative health consequences of unhealthy eating. Emphasis on the short-term consequences of unhealthy eating was stressed by some groups. They suggested that communication campaigns could include adolescents or young adults (maximum 20 years old) suffering the negative health consequences of unhealthy eating, who could share their experience and provide an encouraging message. Other groups indicated that the campaigns should feature impactful messages. For example, one of the groups suggested a graphic piece featuring an adolescent with obesity and the text ‘You don’t want to be like this. Eat healthily’. Other groups of participants put emphasis on the long-term consequences of unhealthy eating, as exemplified in the following messages: ‘You may not realize now, but throughout your life it will have consequences’, ‘What you eat know can harness your future’, or ‘If you eat unhealthy foods, you will die sooner than you think’.

Another approach to the communication campaign was related to raising awareness of the benefits of healthy eating. Adolescents referred to energy, strength and feeling good, as exemplified in the following quotes: ‘Peter always eats healthily and never had health problems. He has a lot of energy and strength. Be like Peter’, ‘The healthier you eat, more vitamins and energy you’ll have’, ‘Eating healthily makes you feel good’, or ‘Be healthy, be powerful’. They also stated that awareness of the benefits of healthy eating could be raised through the experience of football players and athletes. In addition, other groups of participants suggested that campaigns should empower adolescents to make their own informed choices (e.g. ‘We make our own choices. It’s our body’). In this sense, they stated the importance of showing the nutritional composition and ingredients of industrialised foods, as well as their difference from natural foods.

Within the behaviour change communication domain, strategies related to the provision of nutrition education and skills were also mentioned by adolescents. As shown in Fig. 2, they suggested activities in educational institutions to increase knowledge and awareness of the health consequences of unhealthy eating. They also mentioned the implementation of cooking workshops and the provision of information to prepare healthy and tasty dishes from scratch without investing much time and effort. In addition, they suggested that adolescents should be exposed to healthy foods, so that they can learn to enjoy eating them. For this purpose, they suggested blind tastings with culinary preparations based on vegetables.

Although most strategies to encourage healthy eating were related to behaviour change communication, adolescents also identified four types of strategies aimed at modifying the food environment (Fig. 2). Drawing from the experience of tobacco warnings, participants suggested the inclusion of pictorial signs on unhealthy foods to raise awareness of their potential deleterious effects on health. Furthermore, changes in the availability of healthy foods, particularly fruits and vegetables, were identified as a tool to encourage adolescents to consume them. For this purpose, adolescents suggested increasing the number of restaurants offering healthy dishes, as well as stands offering fruits. Restrictions on the sales of unhealthy foods were also mentioned, e.g. by banning sales of unhealthy foods in the canteens of educational institutions. Finally, participants also referred to changes in the price of healthy and unhealthy foods to modify their affordability (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The present work qualitatively explored Uruguayan adolescents’ views on their perceived unhealthy eating habits, with a focus on the foods they consumed and the strategies that can be implemented to promote healthy eating. Adolescents reported frequent consumption of ultra-processed products and fast food, whereas they reported an infrequent consumption of fruits and vegetables. These results are in agreement with several studies on the eating habits of adolescents conducted across the globe(Reference Aljaraedah, Takruri and Tayyem3,8,Reference Taylor, Garland and Sanchez-Fournier26,Reference Verstraeten, Van Royen and Ochoa-Avilés27,Reference Chan, Tse and Tam32,Reference Beck, Iturralde and Haya-Fisher33) . The foods adolescents perceived as good and bad for their health were aligned with the recommendations of the Uruguayan dietary guidelines(34).

According to adolescents’ accounts, deviations from nutritional recommendations can be mainly attributed to the hedonics, lack of perceived risk and susceptibility, as well as environmental factors. Pleasure has been identified as a key driver of the food choices of adolescents(Reference Aljaraedah, Takruri and Tayyem3,Reference Verstraeten, Van Royen and Ochoa-Avilés27,Reference Chan, Tse and Tam32,Reference Beck, Iturralde and Haya-Fisher33,Reference Veeck, Grace Yu and Yu35,Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon36) . Adolescence is a period of increased sensitivity to reward and diminished cognitive control, which may lead to excessive consumptive behaviours(Reference Lowe, Morgon and Reichlet11). In the present work, some participants explicitly referred to ultra-processed products as addictive, stressing the difficulties they face to control their consumption (c.f. Table 1). Hyper palatable ultra-processed foods trigger high levels of reward and cause compensatory mechanisms that result in tolerance, which may disproportionately impact children and adolescents(Reference Gearhardt, Davis and Kuschner37).

The characteristics of the food environment may exacerbate adolescents’ predilection for ultra-processed products. The environments where people live have been reported to be major determinants of their food choices(Reference Raza, Fox and Morris15,Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien38) . Nowadays, adolescents live in an environment characterised by the wide availability and marketing of ultra-processed products and the scarcity of facilitators for healthy eating(Reference Fox and Timmer14,Reference Jonsson, Larsson and Berg17,Reference Verstraeten, Van Royen and Ochoa-Avilés27,Reference Beck, Iturralde and Haya-Fisher33) .

Lifestyle factors such as convenience and time constraints also emerged as major determinants of adolescents’ eating habits. Similar results have been reported by previous studies with adolescents(Reference Verstraeten, Van Royen and Ochoa-Avilés27,Reference Beck, Iturralde and Haya-Fisher33,Reference Veeck, Grace Yu and Yu35,Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon36) . Increased independence around food during adolescence may contribute to unhealthy eating habits as immediate gratification and convenience are prioritised over potential negative health consequences(Reference Weller, Hardy-Johnson and Strommer39–Reference Siu, Lam and Le41). However, it should be stressed that several adolescents identified the family environment as a facilitator for consumption of ultra-processed products due to their convenience. In this sense, previous studies have identified time constraints as a major barrier for favourable dietary behaviour change among Uruguayan adults(Reference Ares, Aschemann-Witzel and Vidal42,Reference Machín, Aschemann-Witzel and Patiño43) . This suggests that changes in the family environment are also needed to trigger long-lasting changes in the eating habits of adolescents.

Multifaceted strategies to promote healthy eating habits emerged from adolescents’ accounts. Most of the strategies were related to the behaviour change communication domain of the NOURISHING framework, which involves the provision of information, education, literacy and skills(Reference Hawkes, Jewel and Allen16). Participants stressed the importance of implementing communication campaigns to raise awareness of the short-term negative health consequences of unhealthy dietary patterns. This suggestion is aligned with adolescents’ present-orientation, i.e. the prioritisation of immediate over long-term consequences(Reference Zimbardo and Boyd40,Reference Siu, Lam and Le41) . According to behaviour change models, motivation to engage in behaviour change is related to the perceived risk and perceived susceptibility(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West44). Not perceiving themselves at risk of the negative consequences of unhealthy eating may prevent adolescents from changing their habits(Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon36,Reference Weinstein45,Reference Knox46) . For this reason, communication campaigns should make adolescents think that they are susceptible to negative consequences in the short term. One of the main challenges of this type of behaviour change campaign is communicating health risks without stigmatising people with obesity. This is particularly relevant during adolescence given that having overweight and obesity has been reported to be associated with an increase in the likelihood of victimisation and social isolation, which negatively affects emotional development and well-being(Reference Puhl, Luedicke and Heuer47,Reference Pearce, Boergers and Prinstein48) . In this sense, it is worth noting that some of the messages proposed by adolescents heavily relied on stigmatisation of adolescents with obesity (e.g. ‘You don’t want to be like this’).

Although emphasis was mainly placed on loss-framed messages, adolescents also suggested a gain-frame to behaviour change communication. They proposed messages stressing the short-term consequences of healthy eating, which may also contribute to behaviour change by increasing perceived benefits(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West44). In addition, empowerment was identified as a relevant characteristic of communication campaigns, which has been recognised as a relevant characteristic of successful approaches to encourage behaviour change and adolescents’ involvement(Reference Spencer20,Reference Ballard and Syme21) . Interestingly, the messages proposed by adolescents for behaviour change communication were focused on health and nutrition. However, no references were made to pleasure, convenience or price, although they were identified as key determinants of their food choices. Promotion of healthier eating habits among adolescents may benefit from the inclusion of references to pleasure and social aspects of food consumption(Reference Pettigrew49,Reference Trudel-Guy, Bédard and Corneau50) .

According to adolescents’ accounts, social media should be the main communication channel for encouraging changes in their eating habits, in agreement with the regular use of social media among adolescents(Reference Reid and Weigle51,52) . Participants from the present study highlighted the importance of including celebrities, such as football players, singers and social media influencers (i.e. online celebrities with a large number of followers), in the communication campaigns. Adolescents are particularly sensitive to social influences, and previous research has shown that celebrities have persuasive power(Reference Rudan53,Reference Erdogan54) . The use of celebrities and social media influencers has been reported to have potential in the context of health promotion(Reference Harris, Atkinson and Mink55). However, it is worth highlighting that celebrities and social media influencers are being increasingly hired by food companies to promote their products(Reference Qutteina, Hallez and Mennes56). In addition, research has shown that social media influencers frequently advertise brands or products, stressing their advantages and personal affinity but without any explicit references to their business model(Reference Pilgrim and Bohnet-Joschko57). Public health organisations are increasingly turning to influencers to boost health campaign reach, despite the challenges associated with the identification of celebrities and social media influencers free of conflict of interest willing to be involved in such campaigns(Reference Kostygina, Tran and Binns58). A successful example is the ‘Left Swipe Dat’ youth smoking prevention campaign, endorsed by prominent social media creators and personalities(Reference Kostygina, Tran and Binns58,Reference Grande59) .

Most of the strategies suggested by adolescents to promote healthy eating relied on individual-focused strategies (behaviour change communication), which have been shown to be not sufficient to achieve relevant behavioural changes at the population level(Reference Contento, Balch and Bronner60). This result suggests that adolescents underestimated the impact of social and environmental factors that shape eating habits and contribute to the development of obesity and non-communicable diseases. Previous studies have reported that people frequently consider that healthy eating habit is a matter of self-responsibility and lack of self-control(Reference Bayer, Drabsch and Schauberger61–Reference Bonfiglioli, Smith and King63). This finding stresses the need to implement education and communication strategies to convey the more complex drivers of eating behaviour to adolescents. An interesting avenue for further research is the co-creation of such strategies with adolescents to empower them to become advocates for comprehensive public policies.

Although adolescents mainly focused on behaviour change communication, they also identified some strategies aimed at changing the food environment: the inclusion of pictorial warnings on food packages, changes in the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods, taxes on unhealthy foods and subsidies on healthy foods. These strategies are part of the NOURISHING framework and have been recommended as part of a comprehensive set of policies to encourage healthy eating worldwide(Reference Hawkes, Jewel and Allen16). Changes in the food environment are expected to be more effective at encouraging changes in the eating patterns of adolescents than communication campaigns(Reference Downs and Demmler64). In particular, a growing body of research shows the effectiveness of nutritional warnings, taxes and subsidies and changes in food availability in school settings(Reference Downs and Demmler64–Reference Thow, Downs and Jan67).

Limitations of the study

Despite its relevance and novelty, the present work is not free of limitations. First of all, the study was exploratory in nature and involved a convenience sample of Uruguayan adolescents recruited at two educational institutions. However, it is worth stressing that results from the present work were in agreement with other studies conducted worldwide and fully aligned with policy recommendations(Reference Aljaraedah, Takruri and Tayyem3,8,Reference Hawkes, Jewel and Allen16,Reference Taylor, Garland and Sanchez-Fournier26,Reference Verstraeten, Van Royen and Ochoa-Avilés27,Reference Chan, Tse and Tam32,Reference Beck, Iturralde and Haya-Fisher33,Reference Downs and Demmler64) . Second, participants may not have been able to fully express their views due to social desirability and peer pressure. Further research should be conducted to expand the findings of the present work and to obtain a more in-depth understanding of how the eating habits of Uruguayan adolescents can be effectively modified.

Conclusions and implications

The results from the present work suggest that strategies to promote healthy eating among adolescents should aim at reducing consumption of ultra-processed foods and increasing the intake of fruits and vegetables. Active engagement of adolescents in the development of such strategies can contribute to increase their efficacy(Reference Ballard and Syme21,Reference Yeager, Dahl and Dweck22) . The present research showed that it is feasible to engage adolescents to obtain relevant insights for policy making, which supports recommendations on involving adolescents in health promotion(Reference Ballard and Syme21–Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers24,Reference Bhutta, Lassi and Bergeron68) . The results showed that adolescents provided relevant insights on barriers and enablers for healthy eating, as well as actionable ideas about strategies to encourage behaviour change. In addition, adolescents’ views also evidenced the need to raise awareness of the social and environmental drivers of eating habits.

Social media can be a successful communication channel to encourage healthy eating habits among adolescents, as previously recommended by Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Merchant and Moreno69) The increasing contribution of digital marketing to the marketing mix of the food industry suggests the potential of this approach(70). In this sense, the collaboration between policy makers, public health organisations and social media influencers can be a promising way of communicating behaviour change messages to adolescents and young adults(Reference Harris, Atkinson and Mink55,Reference Kostygina, Tran and Binns58) . Further research in this regard is warranted.

A central question for the design of communication campaigns is message framing, i.e. whether to stress the benefits of engaging in the target behaviour (gain-frame) or the negative consequences of not engaging in it (loss-frame). In the present work, adolescents suggested both a gain and a loss-frame. Although several studies have explored the moderator effect of message framing on nutrition-related behaviour change, evidence is not conclusive yet(Reference Rosenblatt, Bode and Dixon71,Reference Rothman and Salovey72) . Considering that message framing is prone to contextual sensitivity(Reference Vidal, Machín and Aschemann-Witzel73,Reference Otterbring, Festila and Folwarczny74) , further research should be conducted to evaluate adolescents’ perception of different types of messages, as well as the effect of message framing on the efficacy of strategies aimed at encouraging changes in their eating behaviour. Active engagement of adolescents in the cocreation of the contents can positively contribute to the efficacy of the communication campaign(Reference Yeager, Dahl and Dweck22,Reference Kleinert and Horton23) . In addition, adolescents’ engagement in such strategies can contribute to their empowerment in the promotion of healthy eating.

Adolescents’ emphasis on the addictive characteristics of ultra-processed foods suggests that policy making to encourage healthy eating should draw from the experience of addictive products, such as tobacco and alcohol(Reference Gearhardt, Davis and Kuschner37). In this sense, the implementation of warnings highlighting high nutrient content or their potential negative health consequences, taxes, marketing restrictions and sales bans in educational institutions could be among the strategies to be considered. Further research should be conducted to explore adolescents’ perception and reaction to different policies, such as health warnings and marketing restrictions.

Strategies aimed at familiarising adolescents with healthy foods, particularly fruits and vegetables, and providing cooking skills could also contribute to increase their consumption. Finally, the family environment also needs to be addressed by policy making given its potential to act as a barrier for healthy eating.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the staff from the institutions where the study was conducted. Financial support: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: UNICEF Uruguay, Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica (Universidad de la República) and Espacio Interdisciplinario (Universidad de la República, Uruguay). Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authorship: All authors contributed to the development of the research. G.A., L.A., L.V. and F.A. were involved in data collection and data analysis. G.A. prepared a first version of the paper, to which all other authors then contributed substantially. Ethics of human subject participation: The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects. Approval was obtained from the Ethics committee of the School of Chemistry of Universidad de la República (Uruguay). Written informed consent was obtained from the adolescents’ parents. Adolescents provided verbal assent, which was witnessed and formally recorded.