As early as 1933, the existence of constitutional thinness (CT) had already been mentioned by Erich Grafe(Reference Grafe1), followed by the first observations of Passmore et al. (Reference Passmore, Meiklejohn and Dewar2) and Genest et al. (Reference Genest, Adamkiewicz and Robillard3) in 1955. In a French publication from 1953(Reference Wissmer4), Bernard Wissmer wondered why CT and its treatment had raised so little consideration contrary to obesity. This remark is still valid about 60 years later with obesity and its treatment being widely investigated, while CT remains poorly studied(Reference Estour, Galusca and Germain5). Although there is a growing preoccupation for CT among clinicians due to an increasing number of individuals presenting thinness and seeking to gain weight without apparent criteria of anorexia nervosa (AN), the prevalence of CT remains difficult to determine(Reference Estour, Galusca and Germain5) but would be less than 0·4 % for males and less than 2·7 % for females (underweight from all causes)(6). Despite a large proportion of concerned individuals, many of them do not consult because of a lack of recognition and diagnosis of this condition. Given this lack of interest in the literature, CT is poorly described, which can favour its misunderstanding and misdiagnosis(Reference Estour, Galusca and Germain5), mainly with AN. Although CT and AN are both characterised by a low BMI, people with CT do not present eating disorders, food restriction, psychological disorders or hormonal signs of undernutrition, but present an equilibrated energy metabolism, stable body weight within lower percentiles of growth curve and physiological menses for females(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11). Despite these clinical differences, the distinction between AN and CT remains difficult. Guy-Grand & Badevant proposed a first decision tree to diagnose CT in the early 1980s(Reference Guy-Grand and Basdevant12), but its diagnosis is still debated, especially with the removal of amenorrhoea criterion from the definition of AN in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-5)(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,13) . In our modern societies, individuals with CT have to face social stigmatisation similar to that of anorectic patients(Reference Stewart, Keel and Schiavo14), due to their low body weight and corpulence. Unlike patients with AN, people with CT show an important desire to gain weight, which is the main reason for medical consultation(Reference Estour, Galusca and Germain5). As already noted in 1982(Reference Apfelbaum and Sachet15), the demand of individuals with CT for clinical examination is stereotyped; they are concerned about their thinness and dissatisfied with their morphology usually judged for its lack of femininity for women or virility for men. CT seems then to be a natural state of underweight leading to a high self-dissatisfaction and whose causes remain unclear. While absolute resting energy expenditure was found lower(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10) or similar(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18) in CT individuals v. normal-weight control subjects, resting energy expenditure:fat-free mass ratio was found higher in CT v. control subjects in some studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18) but not significantly higher in some other studies(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19) . Other evidence seems to indicate a more pronounced brown fat activity in CT(Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20). Despite an apparently similar energy intake (quantitatively as well as qualitatively) as normal-weight people(Reference Estour, Galusca and Germain5,Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19) , specific physiological control of appetite has been suggested in individuals with CT(Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23) , with, for instance, an earlier and higher satiety onset during meals leading to reduced but more frequent intakes (more in-between meals snacking)(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10). CT subjects present no eating disorder-related traits and even have lower food restrictive behaviours compared with normal-weight people(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10) . Despite their low BMI, they present a non-blunted fat mass (FM) percentage(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23–Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27) . However, CT people display impairments in their bone quality: small bone sizes, low bone mass, low calculated breaking strength(Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28) and low bone mineral density(Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference Hasegawa, Usui and Kawano26,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28) , but, however, apparent normal bone turnover(Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28). Even if the potential increased risk of osteoporosis with ageing in CT remains to be robustly demonstrated, these bone impairments could be considered as the main co-morbidity associated with CT. This public health concern might not be the only one, but issues in the recognition and diagnosis of CT likely lead to a lack of knowledge. With 2·5 thin subjects per family in CT v. 0·5 in AN, CT is strongly suggested to be a heritable trait likely attributable to genetic factors(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Bulik and Allison29,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30) . Moreover, the exploration of the genetic architecture of thinness demonstrated the polygenic component of CT: genome-wide association studies revealed evidence of loci that could confer susceptibility of CT and also be informative in the identification of potential anti-obesity targets(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30). While there is a growing scientific and clinical interest to better understand and characterise CT, the used inclusion and exclusion criteria remain highly heterogeneous in-between studies, making any comparison and conclusion difficult. This high variability in CT diagnosis underlines today a clear need for a common definition of CT and harmonised criteria that should be used for CT detection. According to the recent literature(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) , parameters such as the terminology used, the characterisation and fluctuation of the level of thinness, the consideration of psychological or physiological illnesses, the weight gain resistance or the level of physical activity appear, a priori, to be the main parameters to focus on in this systematic review. Thus, the present paper proposed a systematic analysis of all the parameters used so far as inclusion criteria of CT individuals in the available studies, trying to suggest a clear definition and diagnostic method of CT.

Materials and methods

The systematic literature search was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42019138236).

Search strategy

The search was conducted on CT and aimed to include any clinical trials enrolling a group of adults with CT. Five electronic bibliographic databases were searched between December 2018 and November 2019: MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL (Cochrane Library), Google Scholar and Clinical Trials. Relevant keywords were discussed and selected between the co-authors. Search terms were also combined with Medical Subject Headings terms. The following syntax was finally used to search on the MEDLINE database: ((constitution[TI] OR constitutional[TI] OR constitutionally[TI]) AND (thinness[TI] OR leanness[TI] OR thin[TI] OR lean[TI])) OR ‘constitutional thinness’ [TW] OR ‘constitutional leanness’ [TW] OR (((resistance[TI] OR resistant[TI]) AND ‘weight gain’ [TI]) NOT ‘insulin resistance’ [TI]) OR (‘thinness/physiology’ [Mesh] OR ((physiological[TI] OR physiologically[TI] OR physiology[TI]) AND (thinness[TI] OR leanness[TI] OR thin[TI] OR lean[TI])) NOT ‘obesity’ [Mesh]) AND (‘humans’ [Mesh] OR ‘humans’ [TW] OR ‘human’ [TW]). Searches were carried out on articles published from 1950. Adapted syntaxes were used to perform the search on the other databases. The authors collectively discussed any discrepancies. All the selected references were then extracted to Zotero Software (5.0.21; Center for History and New Media, George Mason University).

Study eligibility

Inclusion criteria

Clinical trials had to be published in English or French languages and had to enrol constitutional thin/lean adult females or males. Any fields of study could be included in the analysis. However, experiments on animals and clinical trials on children were not eligible for the systematic review. In addition, studies were not included if not enough data were available: letters to the Editor, reviews, abstracts alone or case studies. Only thinness due to a ‘constitutional’ origin was considered. To do this, papers had to mention at least one of these criteria: ‘constitutional thin/lean’ keywords, state of thinness confirmed by measurements, absence of eating disorders, no over-exercising, no associated pathology, physiological menstruations, stable body weight and/or weight gain resistance/desire.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if thinness was not due to a well-identified constitutional origin, such as associated diseases, undernourishment, eating disorders, over-exercising or any ‘non-constitutional’ origins causing a state of thinness. Specific attention was given to the large number of studies that wrongly named their normal-weight control groups as ‘lean’ groups. Normal-weight ‘lean’ control groups were not considered as ‘constitutional lean’ groups and were therefore excluded from the systematic review.

Data extraction and synthesis of results

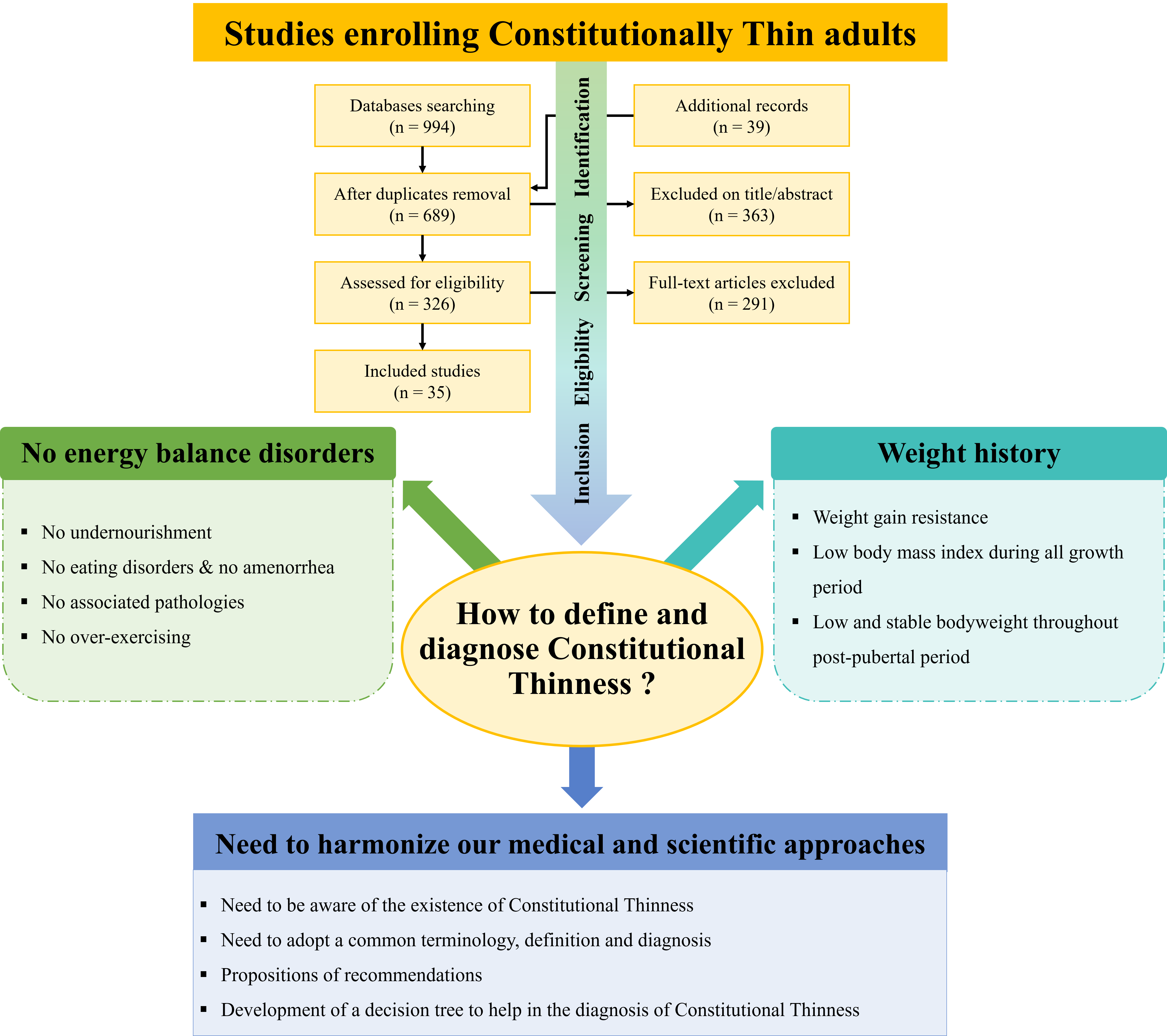

After the removal of duplicates, a first selection was performed on titles and abstracts of studies to assess eligibility of identified records through databases searching. Full-text articles were then screened and included according to the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. At each step of this process, a second screener assessed independently the identification, eligibility and inclusion of papers. Any disagreements about the eligibility and inclusion of papers or about the appraisal of methodological quality were solved by discussing with a third reviewer until a consensus was reached. Potentially relevant references cited in full-text read articles were also added to the initial search. Computer files containing the selected papers at each stage of the selection process were developed and made available to all the co-authors. At the end of the process, thirty-five studies were collectively included in the analysis. The flow diagram of identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion process is provided in Fig. 1. Data extraction of the thirty-five selected papers was performed using a standardised extraction spreadsheet to collect relevant information. As presented in Table 1, relevant information was summarised on established parameters chosen collectively by the authors: reference, population characteristics, definition of thinness, consideration of the absence of eating disorders, consideration of other main parameters and areas of study. We mean by ‘presence of terminology’ (Table 1) the explicit mention of ‘constitutional(ly) thin(ness)/lean(ness)’ keywords. Outcome variables were not assessed in the present work: only the inclusion criteria of the selected studies were considered. Parameters such as food questionnaires or nutritional markers do not appear in Table 1 if these parameters were used as outcomes after the constitution of groups and not as inclusion criteria. Studies are listed in Table 1 according to the publication year, from the oldest to the most recent. Since this systematic review focuses on diagnostic criteria, it was not considered appropriate to retain studies from the same cohorts (recorded as duplicates).

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of the description of the screening, selection and inclusion process.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria used for diagnosis of constitutional thinness (CT) in the clinical trials selected in the systematic review*†

(Numers; mean values and standard deviations)

NR, not reported; C, control subjects; AN, anorexia nervosa; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; NA, not applicable; TFEQ, Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire(Reference Stunkard and Messick48); DEBQ, Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire; EDE, Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; FT3, free triiodothyronine; MOSPA, Monica Optional Study of Physical Activity(Reference Iqbal, Rafique and Badruddin52).

* SCOFF questions, Do you make yourself sick because you feel uncomfortably full? Do you worry you have lost control over how much you eat? Have you recently lost more than one stone in a 3 month period? Do you believe yourself to be fat when others say you are too thin? Would you say that food dominates your life?(Reference Morgan, Reid and Lacey54).

† Areas of study: 1: Energy balance, 2: Body composition, 3: Hormonal, biochemical assays, 4: Appetite-regulating hormones, 5: Bone tissue/Bone markers, 6: Muscle tissue/Muscle function, 7: Genetics or omics approaches, 8: Ophthalmology, 9: Pregnancy, 10: Thermogenesis/Brown adipose tissue, 11: Psychological profile, 12: Cardiology, 13: Functional dyspepsia, 14: Neurology.

‡ Type of values dispersion (sd or sem) not clearly reported.

§ ‘Terminology presence’ means the mention of ‘constitutional(ly) thin(ness)/lean(ness)’ crucial keywords.

Risks of bias

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool(Reference Higgins and Green55) was used to assess the risks of bias, as presented in Table 2. Two authors estimated independently the risks of bias in each included study. The following criteria were assessed: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and selective reporting (reporting bias). Any disagreements were discussed with a third co-author until a consensus was reached. No study was excluded based on the risks of bias.

Table 2. Risks of bias

NR, not reported.

Results

The initial database search yielded a total of 994 studies, and thirty-nine additional studies were also identified. In total, 689 studies remained after the removal of duplicates. After the review of titles and abstracts, 363 studies were excluded: 199 based on title and 164 based on abstract. Thus, 326 full-text articles were scrutinised for eligibility according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, thirty-five studies were considered for analysis (Fig. 1). The risks of bias were estimated with the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool(Reference Higgins and Green55) as presented in Table 2.

Population characteristics

Of the thirty-five studies selected in the systematic review, twenty-six(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) enrolled females exclusively, three(Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39) enrolled males exclusively and six(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) enrolled both females and males (Table 1). Of these thirty-five studies, thirty-two(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30–Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36–Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42–Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) included a normal-weight control group and twenty-three(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20–Reference Marra, Caldara and Montagnese25,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40–Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) included a group of individuals with AN (eighteen(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20–Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) of restrictive type, two(Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41) of both restrictive and binge eating/purging type and three(Reference Marra, Caldara and Montagnese25,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33) did not report the type of AN). Selected studies included sample sizes ranging from six(Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40) to 1622(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30) (both sex) in individuals with CT, from seven(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9) to 10 433(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30) (both sex) in normal-weight control people and from six(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7) to ninety-six(Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35) (both sex) in patients with AN. Studies enrolled participants from 19·4(Reference Marra, Caldara and Montagnese25) to 42·4(Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37) years old in people with CT, from 19·3(Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24) to 52·3(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30) years old (both sex) in normal-weight people and from 15·3(Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35) to 26·4(Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) years old in patients with AN. BMI ranged from 15·7(Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11) to 22·5(Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39) kg/m2 in individuals with CT, from 20·3(Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40) to 27·6(Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39) kg/m2 in normal-weight controls and from 12·0(Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41) to 17·1(Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18) kg/m2 in patients with AN.

Definition of thinness

The ‘constitutional(ly) thin(ness)/lean(ness)’ keywords were mentioned in twenty-eight(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Marra, Caldara and Montagnese25–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30–Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32,Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39–Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) of the thirty-five studies and were therefore not mentioned in the seven remaining studies(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) . Of the thirty-five included studies, thinness threshold was reported through absolute BMI value in twenty-one studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) (ranging from 16·5(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28) to 20·0 kg/m2(Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36)), through BMI percentile in one study (≤ 15th BMI percentile)(Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35), through percentage of ideal body weight in two studies (at least 25 % lower than the average ideal body weight(Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32) or 80–90 % of ideal body weight(Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33)), through silhouette ratings (1: very thin, 9: very large) in two studies (ranging from 1 to 3 for thin females(Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37) and from 1 to 4 for thin males(Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39)), through FM percentage in one study(Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34) (body fat ≤ 20 % and low or normal weight) and through both BMI (< 20 kg/m2) and FM percentage (between 10 and 20 %) in one study(Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46). Thinness threshold was not clearly reported in seven(Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41–Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43) of the thirty-five studies. Weight history was considered in twenty-five(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35–Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41–Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) of the thirty-five studies: four studies(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) reported a stable body weight for a certain period of time before the experiment (ranging from 1 week(Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38) to 2 years(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) ), and twenty-one studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17–Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35–Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) reported it for a longer period throughout the growth period and/or the post-pubertal period. Weight history was not considered in the ten(Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24–Reference Hasegawa, Usui and Kawano26,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32–Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) remaining studies.

Consideration of the absence of eating disorders in individuals with constitutional thinness

Of the thirty-five studies, thirty-two(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30–Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) considered the absence of eating disorders in the inclusion criteria of CT and three(Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) did not consider it. The absence of eating disorders was implicitly confirmed by the presence of a group of patients with AN in twenty-three studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20–Reference Marra, Caldara and Montagnese25,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40–Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) . This absence of eating disorders was confirmed using questionnaires in five studies(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) , interviews in three studies(Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42) and both in one study(Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35). Different questionnaires and thresholds were used: the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire(Reference Stunkard and Messick48) for two studies(Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) with a cognitive restraint score ≤ 5(Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35) or ≥ 13(Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) using their respective version of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire, a food questionnaire with normal scores not further defined for one study(Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36), the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire(Reference van Strien, Frijters and Bergers50) and the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire(Reference Cooper and Fairburn51) without reported thresholds for two studies(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) , the Eating Disorder Inventory Questionnaire(Reference Garner, Olmstead and Polivy53) and the Body Shape Questionnaire(Reference Cooper, Taylor and Cooper47) without reported thresholds for one study(Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31), and the SCOFF questionnaire(Reference Morgan, Reid and Lacey54) without reported thresholds for one study(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30). The Composite International Diagnostic Interview(49) was used for one study(Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R was used for two studies(Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39) and an interview to detect potential lifetime eating disorders in accordance with the criteria of the DSM-IV was used for one study(Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42). The twenty-six remaining studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32–Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) did not mentioned the use of questionnaires or interviews. Three studies(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) presented the following criteria as inclusion criteria: normal insulin-like growth factor-1, oestradiol and free triiodothyronine. Among them, two studies(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) also added normal mean cortisol and non-blunted leptin as inclusion criteria. Under-nutritional markers were not assessed in the thirty-two remaining studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32–Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) .

Consideration of other important parameters in individuals with constitutional thinness

Of the thirty-five studies, twenty-six(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40–Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) mentioned the presence of menses in their group of CT, six(Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38) did not mention it and three studies(Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39) did not enrol females but only males (not applicable criterion). Weight gain resistance/desire was taken into consideration in fourteen articles(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) and was not reported in the twenty-one other selected studies(Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17–Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24–Reference Hasegawa, Usui and Kawano26,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35–Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) . Among them, twelve studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) specifically referred to the idea of a ‘desire’ to gain weight, one study(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16) reported a complaint about being chronically underweight and one study(Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34) identified a difficulty in gaining weight. No studies used the term ‘resistance’ to weight gain. The absence of associated pathology was considered in twenty-eight(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Marra, Caldara and Montagnese25–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30–Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42–Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) of the thirty-five studies but was not reported in the seven remaining studies(Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36–Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41) . Physical activity was reported in thirteen studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Jeandel and Germain22,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Marra, Caldara and Montagnese25,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) and was consequently not reported in the twenty-two remaining studies(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18–Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference Hasegawa, Usui and Kawano26,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32–Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) . Ten articles(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Jeandel and Germain22,Reference Marra, Caldara and Montagnese25,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) just mentioned the absence of over-exercising without questionnaire-based assessment. Among them, two articles(Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) specified that participants did not spend more than 1 h per week on sport activities and one article(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30) excluded all participants who stated that they exercised more than three times a week or with an intensity exceeding six metabolic equivalents for any duration or frequency(56). Three articles(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) used the Monica Optional Study of Physical Activity questionnaire(Reference Iqbal, Rafique and Badruddin52) to assess the absence of over-exercising, and one(Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) of them added intensive physical activity (more than three sessions of physical activity per week) as an exclusion criterion.

Areas of study

Various fields of study were investigated in the selected articles. Of the thirty-five studies included in the systematic review, twenty-one(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40) investigated body composition, nineteen(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference Hasegawa, Usui and Kawano26–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) assessed hormonal or biochemical parameters and fifteen(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20,Reference Hasegawa, Usui and Kawano26,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) studied energy balance of individuals with CT. Investigations were carried out in a total of eight studies(Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41) on appetite-regulating hormones, six studies(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38) on bone tissue or bone markers, seven studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) on psychological profile, five studies(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35) on genetics or omics approaches, four studies(Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) on muscle tissue or muscle function, two studies(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20) on thermogenesis or brown adipose tissue, one study(Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) on ophthalmology, one study(Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32) on pregnancy, one study(Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36) on cardiology, one study(Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42) on functional dyspepsia and one study(Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) on neurology.

Discussion

The literature shows a growing number of clinical trials enrolling underweight participants without apparent disorders in their energy balance, suggesting a constitutional origin of thinness. These studies, however, reveal a high heterogeneity when it comes to the employed definition and diagnosis of CT, as well as a high diversity in the fields of study. In that context, we proposed here a systematic analysis of the clinical trials that enrolled participants with CT in order to propose a better definition and diagnosis of CT.

The need for a clear terminology

The lack of consensus and visibility concerning CT is probably due to the lack of common terminology. Among the thirty-five studies considered in the present systematic review, seven(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) did not used the key terms ‘constitutional thinness’ or ‘constitutional leanness’. This makes highly probable that people might not detect those references while conducting simple scientific or systematic researches. For example, Farooqi and her research team who conducted a very interesting genetic research on CT(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30) preferentially used the ‘persistent/healthy thinness’ expression even if ‘constitutional thinness’ is still found once(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30). In addition, studies enrolling ‘lean’ or ‘underweight’ groups need to be particularly screened. Most of the time, the ‘lean’ term refers to normal-weight individuals and ‘underweight’ term to undernourishment, but confusingly, these terms also remain found in the literature to designate CT individuals. Thus, we would privilege a common terminology, such as ‘constitutional thinness’ or ‘constitutional leanness’ designations. Since CT individuals do not seem to be characterised by a very low body fat percentage despite their low BMI(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23–Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27) , we would favour the terminology of ‘constitutional thinness’ which therefore seems more appropriate than ‘constitutional leanness’. A common terminology would drastically facilitate the referencing of CT in research databases and increase its visibility.

Thinness threshold

As underlined in different studies, dealing with thinness first requires to properly set a threshold for this thinness(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Apfelbaum and Sachet15,57) . The WHO defines different thresholds, based on BMI cut-offs: grade 1 – mild thinness (17·00–18·49 kg/m2), grade 2 – moderate thinness (16·00–16·99 kg/m2) and grade 3 – severe thinness (< 16·00 kg/m2)(57,58) . Thus, the WHO uses the BMI measurement to provide demarcation points. Of the thirty-five included studies, twenty-two(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44–Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) also used BMI cut-offs and one study(Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35) used a threshold of BMI percentile (≤ 15th BMI percentile). BMI cut-offs ranged from 16·5(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28) to 20·0(Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) kg/m2 for studies using a BMI threshold and mean BMI ranged from 15·7(Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11) to 22·5(Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39) kg/m2 in individuals with CT, revealing a high heterogeneity in BMI values. Two studies(Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) used percentages of FM to define a thinness cut-off. From an etymological point of view, ‘leanness’ defines a low body fat content and interestingly, Maffetone et al. proposed the use of the ‘underfat’ term instead of ‘underweight’(Reference Maffetone, Rivera-Dominguez and Laursen59). Nevertheless, Maffetone et al. proposed this terminology considering thinness due to a chronic illness or eating disorders, not thinness due to a constitutional origin(Reference Maffetone, Rivera-Dominguez and Laursen59). Despite their low BMI, CT individuals have been suggested to present a non-blunted FM percentage(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23–Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27) , unlike AN individuals whose FM seems significantly lower compared with CT people(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24) . The use of a body fat percentage threshold does not seem yet adequate to diagnose CT and could, on the contrary, lead to misdiagnosis. While we therefore suggest that ‘underfat’ might not be an appropriate term in the context of CT, further studies using similar inclusion criteria and methodologies are required to provide more evidence about body composition in CT. Two studies(Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33) focused their definition of thinness on a percentage of ideal body weight, and two studies(Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39) argued that silhouette ratings were a better choice to base their definition of thinness. Nevertheless, silhouette ratings led to the inclusion of individuals with a relatively high BMI of 20·3 kg/m2(Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37) in females and 22·5 kg/m2(Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39) in males, whose CT diagnosis was therefore highly debatable. Seven studies(Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41–Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43) did not clearly report any threshold for their definition of thinness. Thus, the systematic review revealed that studies do not systematically point out a cut-off to define thinness. In addition, large variability in both the used criteria and cut-off values was observed. In that context, it seems complex to propose specific recommendations concerning a thinness threshold. However, given the BMI cut-offs of the WHO(57,58) , we would recommend not to enrol CT individuals with a BMI exceeding 18·49 kg/m2.

Weight history

Weight fluctuation and duration of fluctuations are other important parameters that should accompany consideration of the thinness degree. The present systematic review showed that weight history was well taken into consideration with twenty-five studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16–Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35–Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41–Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) reporting this criterion. However, there was a high heterogeneity in modalities: four studies(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) reported a stable weight for a certain period of time before the experiment (ranging from 1 week(Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38) to 2 years(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) ) and twenty-one studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17–Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35–Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) reported it for a longer period throughout the growth period and/or the post-pubertal period. In 1982, Apfelbaum and Sachet already stressed the need to consider the weight history of CT patients and to differentiate between slimness and slimming(Reference Apfelbaum and Sachet15). Indeed, weight history opposes CT from AN(Reference Estour, Galusca and Germain5,Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8) . Contrary to AN that is characterised by a curve break at the onset of anorexic tendencies, the diagnosis of CT should be supported by a low BMI (approximately the 3rd percentile) during all the growth period and by a stable body weight throughout the post-pubertal period(Reference Estour, Galusca and Germain5,Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8) . In addition, CT seems to be a heritable trait(Reference Bulik and Allison29,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30) , leading to CT families(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7). For three generations, an average of 2·5 thin subjects per family is found in CT for only 0·5 per family in AN(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7). Thus, the presence of other thin individuals in familial history can also reinforce a CT diagnosis.

Absence of eating disorders, associated pathology and over-exercising

Potential eating disorders and associated diseases, as well as an energy imbalance caused by a high-energy expenditure through physical activity, need to be taken into account to properly identify CT(Reference Estour, Galusca and Germain5,Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) . In the thirty-five included papers, the absence of eating disorders was well considered: only three papers(Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) did not consider this criterion. Although well considered, this absence of eating disorders is most of the time simply mentioned or implicitly suggested without any details regarding its assessment. Only 26 %(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35–Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) of the included studies used specific tools, like questionnaires or interviews, to confirm the absence of eating disorders, and only two studies(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) have associated questionnaires with the assessment of the following nutritional biomarkers: normal insulin-like growth factor-1, oestradiol, free triiodothyronine, mean cortisol and non-blunted leptin. In addition, questionnaires and interviews used were highly heterogeneous, using different versions, rarely reporting thresholds, and if so, with different thresholds. This observation shows the real need to adopt harmonised and common methods to robustly detect eating disorders. Concerning the absence of associated pathology, this criterion was well considered in the selected papers: only seven studies(Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36–Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41) did not report it. Since some studies may have taken into account some diagnostic parameters without explicitly detailing them in their inclusion process, we assume that some diagnostic parameters may have been slightly underestimated. Regarding physical activity, 63 %(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18–Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24,Reference Hasegawa, Usui and Kawano26,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32–Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45) of the included studies did not report any physical activity level in their inclusion criteria. Ten articles(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Jeandel and Germain22,Reference Marra, Caldara and Montagnese25,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) simply mentioned the absence of high physical activity level and only three articles(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) actually assessed physical activity level, using the Monica Optional Study of Physical Activity questionnaire(Reference Iqbal, Rafique and Badruddin52). Importantly, the relevance of the Monica Optional Study of Physical Activity questionnaire(Reference Iqbal, Rafique and Badruddin52) should be discussed. This questionnaire has been validated(Reference Iqbal, Rafique and Badruddin52) among fifty pregnant women only, and several limitations in the methodological approaches of its validation need to be recognised(Reference Iqbal, Rafique and Badruddin52). The thresholds used to define the different physical activity levels differ: two articles(Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) specified that participants did not spend more than 1 h per week in sport activities, one article(Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) considered the practice of more than three sessions of physical activity per week as an exclusion criterion and one article(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30) excluded all participants who stated that they exercised more than three times a week or with an intensity exceeding six metabolic equivalents for any duration or frequency(56). Altogether, these observations raised a real need to precisely describe the population in terms of type, duration, frequency and intensity of physical activity, not only with validated questionnaires but also with a more objective method such as accelerometry. Interestingly, spontaneous repeated muscle contractions in daily life, like fidgeting, were also suggested to be a relevant parameter to evaluate in CT for future studies(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Pasanisi, Pace and Fonti20,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) .

Weight gain resistance/desire

Of the included articles, less than half of them(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) mentioned weight gain resistance/desire in their inclusion criteria of CT people, and most of these articles have been written by members of the same research team(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) . Of the fourteen articles(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) mentioning this weight gain resistance/desire, twelve(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27,Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) used the idea of a ‘desire’ to gain weight, one study(Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16) mentioned a complaint about being chronically underweight, another study(Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34) reported difficulty in gaining weight and no studies used the term ‘resistance’ to weight gain. Even if the desire to gain weight is actually, most of the time, the main reason for medical consultation in CT(Reference Estour, Galusca and Germain5) and definitely differentiates CT from AN, we suggest here that an individual with CT might not present a strong desire to gain weight despite a physiological weight gain resistance, to the same extent that obesity is not defined as the subject’s ‘willingness’ to lose weight. In the case of CT, it may seem more accurate to define it as a ‘resistance’ to gain weight, which can result in a desire to gain weight – but not necessarily. Indeed, CT was found to be the first human model of physiological weight gain resistance(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10), and several publications proposed supplements and treatments to help CT people gain weight, a few decades earlier(Reference Genest, Adamkiewicz and Robillard3,Reference Wissmer4,Reference Apfelbaum and Sachet15,Reference Aubertin60) or more recently(Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31) . Bulik & Allison even proposed the following definition of CT: ‘constitutional protection against the need to diet in order to maintain a low body weight’(Reference Bulik and Allison29).

Female sex predominance and amenorrhoea

A female sex predominance was observed with twenty-six studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32,Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Petretta, Bonaduce and Scalfi36,Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40,Reference Miljic, Pekic and Djurovic41,Reference Paschalis, Nikolaidis and Theodorou43,Reference Florent, Baroncini and Jissendi-Tchofo45,Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) that were conducted among females exclusively, six studies(Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Ling, Galusca and Hager31,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Santonicola, Siniscalchi and Capone42,Reference Gunes, Yıldırım Bas and Arslan44) on both sex and three studies(Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18,Reference Diaz, Prentice and Goldberg34,Reference Mazzeo, Slof and Tozzi39) in males exclusively. As the systematic review was performed on clinical studies, it seems to us that this observation probably only illustrates the lower consultation rate in men, and we encourage further researches in both sex, as CT is not a sex-specific condition. The presence of menses in the diagnosis of CT was widely taken into account: only six studies(Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30,Reference Schneider, Heard and Bréart32,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35,Reference Slof, Mazzeo and Bulik37,Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38) did not mention this criterion of the thirty-two studies(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7–Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19–Reference Galusca, Zouch and Germain28,Reference Riveros-McKay, Mistry and Bounds30–Reference van Binsbergen, Coelingh Bennink and Odink33,Reference Hinney, Barth and Ziegler35–Reference Bosy-Westphal, Reinecke and Schlörke38,Reference Tagami, Satoh and Usui40–Reference Margaritelis, Theodorou and Kyparos46) enrolling females. Although the absence of amenorrhoea was well considered in the studies, the removal of this criterion from the revised DSM-5(13) can lead to new difficulties in the differential diagnosis between AN and CT(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8). It seems, however, relevant to us to verify the absence of amenorrhoea in the diagnosis of CT.

Recommendations in the diagnosis of constitutional thinness

The systematic review of clinical trials that enrolled participants with CT definitely revealed the real need to adopt both a common terminology and a well-defined diagnosis of CT. Based on the present results, we collectively propose here the key term ‘constitutional thinness’ to be used. Using the ‘constitution’ term to refer to the innate and natural cause of thinness seems of particular interest since it also helps clarify the distinction with other behavioural or pathological origins of thinness. In this respect, it seems essential to systematically exclude energy imbalance caused by inappropriately low energy intake (eating disorders) and/or inappropriately high exercise-induced energy expenditure, using validated tools. Ideally, eating behaviour should be evaluated not only with common validated questionnaires or interviews using specific thresholds but also with the assessment of nutritional biomarkers. If possible, the absence of over-exercising should not only be declarative but also measured with robustly validated questionnaires or even by accelerometry technique. Although amenorrhoea has been removed from the definition of AN in the DSM-5(13), it seems relevant to consider the presence of physiological menstruations in the diagnosis of CT. In addition, weight gain resistance and weight history also need to be taken into consideration in the diagnosis. Finally, the question of defining a strict threshold for thinness remains complex and arbitrary. Even though BMI assessment is associated with various limitations(Reference Maffetone, Rivera-Dominguez and Laursen59), we would tend to favour this measurement as long as it is very common and simple to perform. Conversely, we recommend not to use the percentage of body fat as a maximal threshold since CT does not seem to be characterised by a low body fat percentage(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Germain, Galusca and Caron-Dorval10,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Verney and Meugnier19,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23–Reference Germain, Viltart and Loyens27) . Given the BMI cut-offs of the WHO(57,58) , we propose that CT should not be discussed with a BMI exceeding the value of 18·49 kg/m2. Beyond these essential criteria for CT diagnosis, some studies seem to suggest certain common characteristics in CT groups. In comparison to people with AN, CT individuals might display higher resting energy expenditure and resting energy expenditure to fat-free mass ratio(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Marra, Sammarco and De Filippo18) (although it does not seem significant in two studies(Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Scalfi, Coltorti and Borrelli16) ), non-blunted FM percentages despite their low BMI(Reference Bossu, Galusca and Normand7,Reference Estour, Marouani and Sigaud8,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Marra, Pasanisi and Montagnese17,Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23,Reference Fernández-García, Rodríguez and García Alemán24) , and different profiles of appetite-regulating hormones(Reference Germain, Galusca and Le Roux9,Reference Tolle, Kadem and Bluet-Pajot11,Reference Germain, Galusca and Grouselle21–Reference Galusca, Prévost and Germain23) ). If these types of results were supported by a substantial number of studies and clinical evidence, they could be used as new criteria for the distinction of CT from AN in the future, which remains to be robustly demonstrated. In order to visually synthesise the potential actual recommendations in CT diagnosis, based on this systematic analysis, a decision tree is proposed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Decision tree in the diagnosis of constitutional thinness.

On top of the inclusion criteria used by the selected studies, their methodologies must also be considered when interpreting our results as analysed and presented in our risks of bias table (Table 2). Indeed, as reported in Table 2, thirty-four out of the thirty-five included studies present a high risk for the ‘blinding of participants and personnel’, which might affect the obtained results when it comes, for instance, to the evaluation of energy intake, eating profiles or physical activity that could be influenced by the non-blinding of participants or personnel. This interpretation of our analyses must also consider the high proportion of studies presenting a moderate-to-high risk regarding the attrition bias, or even unreported data.

Conclusion

The present review used a systematic approach to identify any clinical trials that enrolled individuals with CT, particularly focusing on the methods used to define and diagnose CT. The employed methodology led us to identify thirty-five clinical trials enrolling a group of participants with CT. This clearly pointed out a relatively reduced number of studies interested in this condition. In addition, the definition and the diagnostic features of CT were found highly heterogeneous in these studies. Terminology and thinness thresholds do not reach consensus, and a high heterogeneity was also observed regarding the assessment of weight history, weight gain resistance and the presence of physiological menses. The absence of eating disorders, associated pathology or over-exercising was not systematically verified and if so, with various methodological approaches. This systematic review points out the essential need not only to be aware of the existence of CT but also to harmonise our medical and scientific practices in the definition and diagnosis of CT. Altogether, the present results led us to propose a decision tree that could help practitioners and researchers better define and diagnose CT, in a potentially more harmonised way. Importantly, not only the proposed decision tree has been elaborated based on clinically relevant indicators that have to be considered for the diagnosis of CT, but it also proposes different alternative evaluations (from self-reported eating questionnaires to under-nutritional physiological markers for instance), guaranteeing its clinical feasibility and applicability.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the documentalists of the Health Library of Clermont Auvergne University for their help in the article search process.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conceptualisation, piloting of the study selection process and formal screening of search results against eligibility criteria: M. B., J. V. and D. T.; data extraction and analysis: M. B.; writing the article: M. B.; supervision and revision of the article: J. V., D. T., N. G., B. G. and D. C.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Target article

Definition and diagnosis of constitutional thinness: a systematic review

Related commentaries (2)

Constitutional thinness: body fat metabolism and skeletal muscle are important factors

Invited Letter to Editor in response to: Constitutional thinness: body fat metabolism and skeletal muscle are important factors