3.1 Introduction

If this book were a Twitter thread, then this chapter on ‘Advances in Feminizing the WTO’ could simply read: ‘For the first time since its establishment, the WTO is put under the leadership of a woman.’ It might continue: ‘Starting in 2021, all three global institutions responsible for trade are led by women’ (ending with an appropriate emoji 🙋♀).

However, there is much more to be said about the advances (or lack thereof) in work on recognizing the complex linkages between trade and gender, and this deserves a book chapter. This chapter was drafted while the WTO members, the Secretariat, and many interested parties, were readying themselves for the WTO MC12 planned to be held from 30 November to 3 December 2021 in Geneva, Switzerland.Footnote 1 Twenty-five years ago, during the 1st Ministerial Conference (MC1) held in Singapore, WTO members debated about, inter alia, the rationale for introducing (core) labour standards into the body of the multilateral rules governed by the (then) newly established WTO. While the Ministers dismissed such proposals,Footnote 2 the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) report (1996), dedicated to concerns related to the agenda of MC1, included a discussion on the impacts of trade liberalization on women.Footnote 3 In fact, the recommendations were rather broader, encompassing: (a) further study to ensure that liberalization policies did not exacerbate existing gender inequalities; (b) systematic and periodic gender-impact assessments of liberalization policies at the sectoral, national, and international levels; (c) further study of existing gender inequalities on trade and investment policies; (d) enabling policymakers to raise these issues within the context of the WTO and other policy-making institutions; (e) setting up a committee within the WTO to examine all the issues from a gender perspective (and incorporating women’s voices on the setting up of WTO agendas); and (f) commitment of sufficient financing to a global gender equity fund).Footnote 4 It is thus only fitting that a quarter-century and eleven ministerial conferences later, the Ministers, once they meet, will have an opportunity to deliberate and finally adopt an ambitious and progressive WTO work programme on Trade for Women. The opportunity that was, after all, missed.

This chapter takes the recommendations by Mikic and Sharma on the steps towards feminizing the WTO and examines if any work associated with these recommendations has indeed occurred and in what form.Footnote 5 As a visual aid, the plan and summary of the chapter’s content is given in Table 3.1. The recommendations refer to five areas, each covered in one section of the chapter. Section 3.2 provides an update on the IWG’s work and the engagements of the WTO members contributing to that work (known as the Friends of Gender). Section 3.3, based on the limited information available,Footnote 6 gauges how much of the IWG’s work programme has permeated into overall WTO operations as well as into the members’ other approaches to trade liberalization. In other words, it assesses to what degree the ongoing negotiations of trade rules/structural discussions on joint statement initiatives (that is, investment facilitation, e-commerce, and MSMEs) have a gender lens. Section 3.4 offers information on the novel work of the Secretariat (as well as other organizations and partners, and in some cases members), improving the evidence and tools necessary to make informed decisions or to make better impact assessments. Section 3.5 comments briefly on the capacity-building work emerging in the Secretariat based on the announcement of a new strategy for the period from 2021 to 2026. Section 3.6 circles back to the role of women in leading trade and trade policy work through reviewing the advancement of women into leadership and decision-making positions in the WTO Secretariat and among the members’ representatives in the WTO. Section 3.7 concludes.

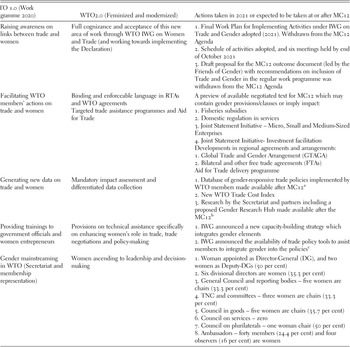

Table 3.1 Advancing from WTO 1.0 to WTO 2.0

| WTO 1.0 (Work programme 2020) | WTO2.0 (Feminized and modernized) | Actions taken in 2021 or expected to be taken at or after MC12 |

|---|---|---|

| Raising awareness on links between trade and women | Full cognizance and acceptance of this new area of work through WTO IWG on Women and Trade (and working towards implementing the Declaration) | 1. Final Work Plan for Implementing Activities under IWG on Trade and Gender adopted (2021). Withdrawn from the MC12 Agenda 2. Schedule of activities adopted, and six meetings held by end of October 2021 3. Draft proposal for the MC12 outcome document (led by the Friends of Gender) with recommendations on inclusion of Trade and Gender in the regular work programme was withdrawn from the MC12 Agenda |

| Facilitating WTO members’ actions on trade and women | Binding and enforceable language in RTAs and WTO agreements Targeted trade assistance programmes and Aid for Trade | A preview of available negotiated text for MC12 which may contain gender provisions/clauses or imply impact: 1. Fisheries subsidies 2. Domestic regulation in services 3. Joint Statement Initiative – Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises 4. Joint Statement Initiative- Investment facilitation Developments in regional agreements and arrangements: 1. Global Trade and Gender Arrangement (GTAGA) 2. Bilateral and other free trade agreements (FTAs) Aid for Trade delivery programme |

| Generating new data on trade and women | Mandatory impact assessment and differentiated data collection | 1. Database of gender-responsive trade policies implemented by WTO members made available after MC12Footnote a 2. New WTO Trade Cost Index 3. Research by the Secretariat and partners including a proposed Gender Research Hub made available after the MC12Footnote b |

| Providing trainings to government officials and women entrepreneurs | Provisions on technical assistance specifically on enhancing women’s role in trade, trade negotiations and policy-making | 1. IWG announced a new capacity-building strategy which integrates gender elements 2. IWG announced the availability of trade policy tools to assist members to integrate gender into the policiesFootnote c |

| Gender mainstreaming in WTO (Secretariat and membership representation) | Women ascending to leadership and decision-making | 1. Woman appointed as Director-General (DG), and two women as Deputy-DGs (50 per cent) 2. Six divisional directors are women (35.3 per cent) 3. General Council and reporting bodies – five women are chairs (33.3 per cent) 4. TNC and committees – three women are chairs (33.3 per cent) 5. Council in goods – five women are chairs (35.7 per cent) 6. Council on services – zero 7. Council on plurilaterals – one woman chair (50 per cent) 8. Ambassadors – forty members (24.4 per cent) and four observers (16 per cent) are women |

a For the database on gender provisions in RTAs, see WTO, ‘Database on Gender Provisions in RTAs’ <www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/womenandtrade_e/gender_responsive_trade_agreement_db_e.htm> accessed 13 September 2022.

b For the Gender Research Hub information, including the research database on trade and gender, see WTO, ‘Research Database on Trade and Gender’ <www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/womenandtrade_e/research_database_women_trade_e.htm> accessed 13 September 2022.

c According to the WTO Secretariat’s statement, this trade policy tool package will include (a) An extensive questionnaire that members could use (fully or partially) to integrate a full chapter into their trade policy reports or to assess how gender has been integrated into their trade policies; (b) A checklist derived from the questionnaire that can be used for the same purpose; (c) A guidebook to support members in this exercise; (d) Indicators that can help members understand how trade rules can be implemented with a gender lens. The first set of indicators will be developed for the Trade Facilitation Agreement. This package is complementary to the ITC’s SheTrades Policy Outlook. As the tool is not publicly available at the time of finalizing this chapter, it is not possible to provide further comments on it. See WTO, ‘WTO Secretariat Talking Points’ (16 July 2021) <www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/womenandtrade_e/16july21/statement_from_wto_secretariat.pdf> accessed 8 May 2022.

The first two columns of Table 3.1 were presented by Mikic and Sharma as the pre- and post-feminization reform states of the WTO. The first column – WTO 1.0 – reflects what has been described as a gender-blind trade system that existed when the Buenos Aires declaration was adopted, but not fit to tackle the contemporary challenges to trade, not least because of not providing for women in trade. The second column – WTO 2.0 – describes the attributes of the trade rules system after the ambitious Buenos Aires declaration and other developments. WTO 2.0 by no means indicates that no further advances concerning the feminization of the WTO should be needed or expected. Nevertheless, WTO 2.0 would already be an advanced environment in which women would benefit from trade and contribute to trade policymaking more than at present. The third column of Table 3.1 lists the actions already taken in preparation for MC12, such as drafted and pre-negotiated statements, declarations, and other documents, and the decisions that need to be taken at MC12 to move the work forward.

It is obvious from Table 3.1, and more explicitly discussed by Mikic and Sharma, that the approach to the analysis of trade and gender issues in the context of the WTO needs to look at the organization from two perspectives: (1) as an international organization, and (2) as a set of various trade rules which form a so-called multilateral trading system. Trade and gender discussion related to the WTO as an international organization boils down to the following: (1) implementation of the mandates from the membership (i.e., Declaration on promoting women’s empowerment); (2) delivery of technical assistance/capacity building for its members to improve formulation and implementation of gender-responsive trade policies and market-opening instruments; (3) generation and delivery of data, tools, and analysis relevant for evidence-based policy-making of members; and (4) finally, improving the gender composition of staff in the organization so as to enable the promotion of women into leadership positions (as well as to support members in this regard) and to promote gender equality. Looking at Table 3.1, rows 1, 3, 4, and 5 include initiatives and actions addressing trade and gender issues from the perspective of the WTO as an organization. When looking at the WTO as a set of rules for trade policies, which, in turn, determine how these policies impact women,Footnote 7 the focus is on how the gender lens is used when negotiating multilateral and plurilateral trade rules (Table 3.1, row 2).

3.2 Let’s Make It Formal

It was almost three years after the 11th Ministerial Conference (MC11) in 2017 delivered the Buenos Aires Declaration on Trade and Women’s Economic Empowerment calling for greater inclusion of women in trade and trade policy-making that there was any action.Footnote 8 Initially supported by 118 members and observers, this number has risen to 127 as of September 2022, which still leaves about one-third of members and observers sitting on the fence, including India, South Africa, and the United States.

It took an initiative by Botswana and Iceland to put together an IWG on Trade and Gender, which was inaugurated in September 2020 in a virtual meeting as per the new pandemic norm.Footnote 9 After a meeting in late 2020, the first regular (and again virtual) meeting of the IWG was in February 2021 and it resulted in adoption of the Schedule of Activities in 2021 (January–July) and a Draft Work Plan, which was soon revised into the Final Work Plan.Footnote 10 The two initial co-chairs were joined by El Salvador in April 2021 and the IWG continued working with the Friends of Gender (comprising nineteen members and observers, four international organizations and the Secretariat) towards a strong delivery for the MC12. Throughout still pandemic-affected 2021, the IWG had six meetings by the end of October, with another scheduled for 24 November. The work of the group evolved around the four pillars stipulated in the Buenos Aires Declaration, and meetings were planned to feature members’ experiences (best practices) in promoting women’s economic empowerment, the most relevant recent research by the Secretariat and its partners, to discuss delivery of the Aid for Trade activities and efforts to clarify the meaning of the ‘gender lens’ and how it applies to the work of the WTO.Footnote 11

After an active year, at the first anniversary meeting in September 2021, the IWG announced the draft MC12 outcome document containing recommendations for WTO members to continue work on increasing women’s participation in international trade. The intention of this document was to convince members to include ‘women’s economic empowerment issues into the regular work of WTO bodies, improve the impact of Aid for Trade on women by mainstreaming gender considerations into programmes and strategies, increase data collection, and coordinate research’.Footnote 12 Unfortunately, due to the complex geopolitical situation resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, this proposal never reached the MC12 Agenda. It was replaced with a rather unambitious ‘[s]tatement on inclusive trade and gender equality from the co-chairs of the Informal Working Group on Trade and Gender – Twelfth WTO Ministerial Conference’.Footnote 13 Instead of producing formalized work on Trade and Gender in the WTO and giving a boost to potential conversion from its current plurilateral mode to a multilateral one,Footnote 14 one paragraph almost at the end of the MC12 Outcome Document referred to, inter alia, work on trade and gender.

Nevertheless, members in the Friends of Gender and the co-chairs of the IWG ought to be commended for their initiative in turning the Buenos Aires Declaration that had lain dormant into an active work plan pre-MC12 as well as on the achievements in the aftermath of the MC12.

3.3 Enforceable (or Any?) Provisions towards Women’s Economic Empowerment

Admittedly, not all WTO members are keen to see the use of a gender perspective when deciding on their trade policies. There is a rich literature on how trade and trade policies may impact women in their roles as consumers, entrepreneurs, workers, or taxpayers, from both export and import (import competition) perspectives.Footnote 15 This literature explains the mechanisms through which trade impacts women’s welfare (well-being) and not only their economic prosperity. It is important that policymakers (including officials in the relevant ministries and parliamentarians) understand these mechanisms as they are most often responsible for providing the negotiating mandate to negotiators who then must follow it in multilateral or other levels of negotiation.Footnote 16 Not to be forgotten, trade reforms that countries undertake on their own (so-called unilateral policies) often have the strongest impact on economic actors, including women.

As we saw, the proposals and requests to consider a gender lens when setting either trade-restricting or trade-expanding policies date many years back. However, our focus here is to identify if there was any ‘leakage’ from the Buenos Aires Declaration and the establishment of the IWG with its work plan into the texts that members were considering for negotiation and adoption at the MC12. Even a few days before the new date of the MC12, only a limited number of documents were publicly available as most of the negotiating texts were still ‘open for negotiations’. As a default option, a conversation with experts and ‘insiders’ was used to inform (considering confidentiality) on the existing gaps. Furthermore, in December 2021, several documents were released enabling us to check whether or not they remain ‘gender-blind’.Footnote 17

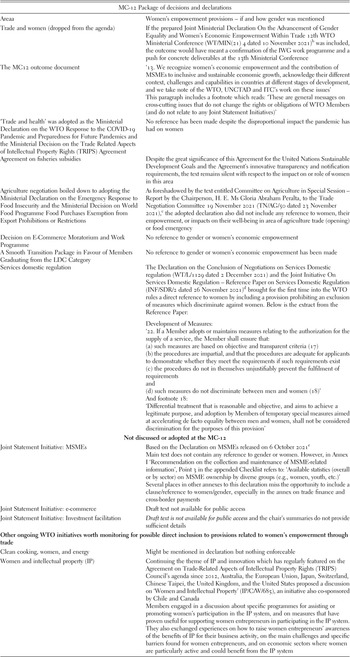

Table 3.2 combines agenda items of the MC12 (including those that were expected but in the end were dropped for geopolitical reasons) with an assessment of to what extent a gender lens is present.

| MC-12 Package of decisions and declarations | |

|---|---|

| Areaa | Women’s empowerment provisions – if and how gender was mentioned |

| Trade and women (dropped from the agenda) | If the prepared Joint Ministerial Declaration On the Advancement of Gender Equality and Women’s Economic Empowerment Within Trade 12th WTO Ministerial Conference (WT/MIN(21) 4 dated 10 November 2021)Footnote b was included, the outcome would have meant a confirmation of the IWG work programme and a push for concrete deliverables at the 13th Ministerial Conference |

| The MC12 outcome document | ‘13. We recognize women’s economic empowerment and the contribution of MSMEs to inclusive and sustainable economic growth, acknowledge their different context, challenges and capabilities in countries at different stages of development, and we take note of the WTO, UNCTAD and ITC’s work on these issues’ This paragraph includes a footnote which reads: ‘These are general messages on cross-cutting issues that do not change the rights or obligations of WTO Members (and do not relate to any Joint Statement Initiatives)’ |

| ‘Trade and health’ was adopted as the Ministerial Declaration on the WTO Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic and Preparedness for Future Pandemics and the Ministerial Decision on the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement | No reference has been made despite the disproportional impact the pandemic has had on women |

| Agreement on fisheries subsidies | Despite the great significance of this Agreement for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the Agreement’s innovative transparency and notification requirements, the text remains silent with respect to the impact on or role of women in this area |

| Agriculture negotiation boiled down to adopting the Ministerial Declaration on the Emergency Response to Food Insecurity and the Ministerial Decision on World Food Programme Food Purchases Exemption from Export Prohibitions or Restrictions | As foreshadowed by the text entitled Committee on Agriculture in Special Session – Report by the Chairperson, H. E. Ms Gloria Abraham Peralta, to the Trade Negotiation Committee 19 November 2021 (TN/AG/50 dated 23 November 2021),Footnote c the adopted declaration also did not include any reference to women, their empowerment, or impacts on their well-being in area of agriculture trade (opening) or food emergency |

| Decision on E-Commerce Moratorium and Work Programme | No reference to gender or women’s economic empowerment |

| A Smooth Transition Package in Favour of Members Graduating from the LDC Category | No reference to gender or women’s economic empowerment has been made |

| Services domestic regulation | The Declaration on the Conclusion of Negotiations on Services Domestic regulation (WT/L/1129 dated 2 December 2021) and the Joint Initiative On Services Domestic Regulation – Reference Paper on Services Domestic Regulation (INF/SDR/2 dated 26 November 2021)Footnote d brought for the first time into the WTO rules a direct reference to women by including a provision prohibiting an exclusion of measures which discriminate against women. Below is the extract from the Reference Paper: Development of Measures: ‘22. If a Member adopts or maintains measures relating to the authorization for the supply of a service, the Member shall ensure that: (a) such measures are based on objective and transparent criteria (17) (b) the procedures are impartial, and that the procedures are adequate for applicants to demonstrate whether they meet the requirements if such requirements exist (c) the procedures do not in themselves unjustifiably prevent the fulfilment of requirements and (d) such measures do not discriminate between men and women (18)’ And footnote 18: ‘Differential treatment that is reasonable and objective, and aims to achieve a legitimate purpose, and adoption by Members of temporary special measures aimed at accelerating de facto equality between men and women, shall not be considered discrimination for the purposes of this provision’ |

| Not discussed or adopted at the MC-12 | |

| Joint Statement Initiative: MSMEs | Based on the Declaration on MSMEs released on 6 October 2021Footnote e Main text does not contain any reference to gender or women. However, in Annex I ‘Recommendation on the collection and maintenance of MSME-related information’, Point 3 in the appended Checklist refers to: ‘Available statistics (overall or by sector) on MSME ownership by diverse groups (e.g., women, youth, etc.)’ Several places in other annexes to this declaration miss the opportunity to include a clause/reference to women/gender, especially in the annex on trade finance and cross-border payments |

| Joint Statement Initiative: e-commerce | Draft text not available for public access |

| Joint Statement Initiative: Investment facilitation | Draft text is not available for public access and the chair’s summaries do not provide sufficient details |

| Other ongoing WTO initiatives worth monitoring for possible direct inclusion to provisions related to women’s empowerment through trade | |

| Clean cooking, women, and energy | Might be mentioned in declaration but nothing enforceable |

| Women and intellectual property (IP) | Continuing the theme of IP and innovation which has regularly featured on the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Council’s agenda since 2012, Australia, the European Union, Japan, Switzerland, Chinese Taipei, the United Kingdom, and the United States proposed a discussion on ‘Women and Intellectual Property’ (IP/C/W/685), an initiative also co-sponsored by Chile and Canada Members engaged in a discussion about specific programmes for assisting or promoting women’s participation in the IP system, and on measures that have proven useful for supporting women entrepreneurs in participating in the IP system. They also exchanged experiences on how to raise women entrepreneurs’ awareness of the benefits of IP for their business activity, on the main challenges and specific barriers found for women entrepreneurs, and on economic sectors where women are particularly active and could benefit from the IP system |

a WTO, ‘Twelfth Ministerial Conference’ <www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc12_e/mc12_e.htm#outcomes> accessed 13 September 2022.

b WTO, ‘Joint Ministerial Declaration on the Advancement of Gender Equality and Women’s Economic Empowerment Within Trade 12th WTO Ministerial Conference’, WT/MIN21/4 (10 November 2021).

c WTO, ‘Committee on Agriculture in Special Session – Report by the Chairperson, HE Ms Gloria Abraham Peralta to the Trade Negotiations Committee’, TN/AG/50 (23 November 2021).

d WTO, ‘Declaration on the Conclusion of Negotiations on Services Domestic Regulation’, WT/L/1129 (2 December 2021).

e WTO, ‘Informal Working Group on MSMEs, Declaration on Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (MSMEs)’, INF/MSME/4/Rev.2 (6 October 2021).

The content of Table 3.2 does not invoke optimism that the WTO members will be embracing the recommendations on including strong and enforceable women’s economic empowerment provisions in the WTO agreements any time in the near future. There is, of course, a continued risk that any new type of provisions able to impact trade flows might be abused as a new form of protectionism (e.g., green and environmental provisions, labour, health, and, indeed, gender). The danger of using these in a discriminatory fashion is much greater in the absence of any international rules to guide (and constrain as necessary) the behaviour of policymakers.

Furthermore, there is evidence that members have moved on with creative approaches to opening the markets to keep trade and investment going albeit outside the multilateral space. Some pursued these alternative rules (typically regional or bilateral, rarely unilateral), arguing that the multilateral route is not effective. Examples include so-called deep preferential trade agreements or sectoral agreements covering digital trade, known as digital economy partnership agreements (DEPAs).Footnote 18 Cynics would argue that it was because the non-most-favoured-nation (MFN) route allowed for more selective discrimination.Footnote 19 Notwithstanding, the same creativity should be used when it comes to promoting women’s economic empowerment through trade agreements. There were some very promising alternative arrangements and agreements that can work easily at the MFN level and can support modernization of the multilateral trade system. These include deep regional trade agreements with separate chapters (provisions) on driving women’s economic empowerment through trade. Examples include most of the recent bilateral FTAs of Canada but also the plurilateral GTAGA, signed initially by New Zealand, Chile, and Canada and now joined by Mexico.Footnote 20 This is not a trade agreement, but a cooperation arrangement where countries can exchange lessons on both domestic policies and trade policies.Footnote 21 Readers interested in more details on this topic can refer to several other chapters in this volume which address trade and gender at the level of regional and bilateral trade and investment agreements in more detail than is possible in this chapter.Footnote 22

3.4 Impact, Impact, Impact

An impact assessment has become an integral process of trade policy-making. No policy change – including trade-restricting/expanding policies at any level – should be passed to an implementation phase without prior scrutiny and ex ante impact assessment. Referencing the European Union’s mandatory ex ante or ex post impact assessment of proposed agreements of grant of preferences, Mikic and Sharma proposed that an ‘efficient strategy for the inclusion of a gender lens approach in trade agreements could be the inclusion of a mandatory impact assessment of proposed agreements wherein if an agreement does not contribute to women’s economic empowerment, it would not pass the “RTA transparency mechanism” review’.Footnote 23 This will be a step ahead of what the Buenos Aires Declaration proposed in terms of collection and sharing of better quality data, which will be able to be mined for deeper insights into the impacts of trade on women as well as how women may impact trade.Footnote 24

As with some other instances where data availability takes the blame for lack of transparency or weak analytical work, most often an absence of solid gender-impact assessment of trade policy changes is explained by lack of data. As a member-driven institution, the WTO also falls into this mould of waiting for the members to supply data (which potentially might produce results not working in the interest of these members). The only solution is for the Secretariat to dedicate some of its own (very capable) human resources and in partnership with other international institutions, think tanks, and other actors and produce data and analysis necessary for gender-responsive policy-making. The first nudge for the Secretariat to move in this direction came with the Global Financial Crisis and calls for better monitoring of the use of discriminatory trade policies to which the Secretariat responded by producing six-monthly monitoring reports for G20 countries, responsible for the lavish share of global trade.Footnote 25 The COVID-19 pandemic was another strong impetus for the Secretariat to ‘get out there’, collect data, and provide members with evidence on how the pandemic impacted their trade (and more) as well as how the organization of global trade might have been impacting the members’ capacity to respond to the pandemic. The Secretariat has responded to this challenge, and many members have been better informed and their decisions positively affected by the information and research available to all at the dedicated pages on ‘COVID-19’ and ‘Trade’.Footnote 26

Similarly, the Secretariat made progress in terms of collection of data and production of research, helping better policy-making. First, it produced a new Trade Cost Index, which provides more insights into determinants of trade costs and their burden with respect to different income groups and most importantly women and men separately.Footnote 27 This new methodology allows trade costs to be tracked for eighteen years for over forty countries.Footnote 28 Figure 3.1, reproduced from the Secretariat’s note,Footnote 29 shows that women have been burdened with higher trade costs throughout the observation period.

Figure 3.1 Global export cost index by gender.

As indicated in Table 3.1, the Secretariat announced that it will provide another novel database collating all gender-responsive trade policies implemented by WTO members. This database is sourced by information from members’ trade policy reports and independent research produced by the Secretariat and other agencies. It also includes the gender provisions contained in various trade agreements that members have concluded.Footnote 30

In 2021, the WTO launched the WTO Gender Research Hub to enhance collaboration and exchange among researchers and analysts working on the linkages between trade and gender. The Hub will also serve as a platform for dialogue between researchers and the IWG. The main participants in the Hub are the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the UNCTAD, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank Group (WBG), the ITC, the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), three holders of the WTO Chairs Programme (Chile, Mexico, and South Africa), and individual academics.Footnote 31

3.5 First, Teach a Woman …

The WTO has been providing trade-related technical assistance (TRTA) to its members (and other stakeholders) since its establishment – expanding it from what was available during the era of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Increasingly, the focus of the assistance has moved from negotiation to implementation, building capacity for trade policy-making and transparency. In support of Trade for Women, TRTA will also need revamping. According to the Secretariat’s note on the new training strategy for 2021–2026,Footnote 32 the programme will combine tools to support WTO members, providing them access to concrete solutions for integrating gender into trade policies and for implementation of trade rules with a gender lens. It comprises a multi-pronged approach offering a regular course on trade and gender; training for the delegates in Geneva; online training; and national-level activities upon request.

In addition to the training on trade and gender linkages, which aims for gender-balanced participation, there is a need to enhance the capacity of women as negotiators, policymakers, policy influencers, and traders. As already noted by Mikic and Sharma, additional efforts should be made to close the knowledge gap for women working in trade.Footnote 33 As was exposed through the pandemic, lack of digital literacy for business (not to mention access to digital infrastructure) has undermined the capacity of millions of women to cope with the pandemic-initiated crisis and caused further social and economic inequalities.Footnote 34 At the same time, the unpreparedness of national regulations to absorb the move to digital trade, online payments, and digitalization in general, made the situation in many developing countries hit by the triple crises of 2020 even worse. A crisis such as the world has been experiencing since January 2020 proves how important it is to have access to physical and natural capital to address external and internal shocks, but also, most importantly, to human capital. If we neglect improving the skills and knowledge of (about) half of human potential, we risk not being able to respond to these challenges. We are talking about 50 per cent of the population on average being women, so we must have at least such a ratio when we create human capital, in trade and in all other fields.

3.6 No More Glass Ceilings for Women in Trade?

There is a rich body of literature on the establishment of the international organization to govern trade, from the drafting of the 1948 Havana Charter to the 1994 Marrakesh Agreement and more which are not the subject matter of this chapter. However, very often – if not always – when Secretariat staff talk about the WTO, they categorize it as ‘the member-driven organization’, implying the existence of (possibly significant) limitations on the independent work of the Secretariat (this has been more recently and intensively discussed in the context of the role of WTO in the pandemic).Footnote 35 While these constraints impact appointments at the highest level of management (as documented by the appointment of the current Director-General), the author of this chapter holds that these constraints do not apply to the recruitment of divisional directors and other staff in the Secretariat.Footnote 36

In the absence of newer gender-differentiated statistics for the whole Secretariat, the comments here pertain to management level only. Naturally, one must start with the historic appointment of Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala as the first woman Director-General. She then proceeded to make history by appointing two women as Deputy Director-Generals (or 50 per cent) which is a clear break with the past. The improvements with respect to women’s share in the management positions within the Secretariat do not stop here. At present, six out of seventeen divisional directors are women (35.3 per cent).Footnote 37 That is almost double the share Mikic and Sharma reported (18 per cent).Footnote 38

When it comes to the gender composition of the members’ representatives in the WTO, these numbers also show an improvement, although small.Footnote 39 At present, no woman chairs the Council or the Committees. However, 33.3 per cent of chairs of the bodies reporting to the General Council are women; similarly, 33.3 per cent of chairs in the Trade Negotiating Committee are women, 35.7 per cent in the council on Goods, and 50 per cent in the Council on Plurilaterals. Only the Council on Services has no woman engaged as a chair. These chairs come from the forty women ambassadors (24.4 per cent) from the members’ group and four from the WTO observers (16 per cent), which is still a significant underrepresentation of women in the most important global trade governance body.

With the ceiling seemingly being removed, the sky should be the limit. A plethora of initiatives bringing together women working in the area of trade and trade policy-making shows that there is both demand and supply for such self-organized and -driven communities aiming to strengthen women’s role as influencers in the public and private sectors. Women hold an enormous amount of knowledge and skills relevant for making trade contribute to sustainable development and thus women should be actively encouraged to play their role in the trade community.

3.7 Conclusion

We have come a long way since it was acceptable to claim that trade as an economic activity and trade policy as part of economic coordination is gender neutral. It is indisputable that trade policies can (and should) be used to advance the economic and social well-being of women. Women have been, and increasingly will be, directly involved in making critical and path-changing decisions at national, regional, and global levels on how trade could be used to promote sustainable development.

Based on the performance of women in decision-making and leadership positions during the last two years of the pandemic, we should be actively placing women into jobs and roles with responsibilities for tackling current and emerging crises. Not only that, but we should also look more decisively to removing obstacles that prevent women from employing their full potential and contributing to generate prosperity and more just, responsible societies.

In this chapter, we attempted to find out about the progress of the feminization of the WTO, which is our shorthand for the implementation of the Buenos Aires Joint Declaration on Trade and Women’s Economic Empowerment. While 127 WTO members and observers had joined in this Declaration, apparently showing an overwhelming interest in supporting women’s economic empowerment, it still did not convert into a more ambitious self-standing MC12 multilateral declaration. Furthermore, following our review of how much of this support was translated into changes of trade rules to promote women’s economic empowerment and engagement of women in trade, we were not impressed. Among all of the members’ work on new rules or directions for the WTO’s reform, only one (joint initiative on Services Domestic Regulation) includes a reference to gender-responsible trade policy. Despite evidence of the great importance of fisheries, agriculture, and MSMEs for women, the members missed the opportunity to build in adequate promoting provisions. While one must appreciate the existence of some progress (‘WTO is not gender blind anymore’Footnote 40), there is no time for complacency. If there is any chance for the disproportionate burden that women have been carrying throughout the pandemic (as in so many other crises) to be shifted and rebalanced, trade policy must become more gender responsible. The time has come to accept that work on women’s equality in trade is the core of the trade agenda.