43 results

Chapter 1 - ‘everybody eating everyone else’

-

- Book:

- Vegetarianism and Veganism in Literature from the Ancients to the Twenty-First Century

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 1-19

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Behind the Structures and the Subject

-

- Book:

- Intellectual History and the Problem of Conceptual Change

- Published online:

- 02 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 09 May 2024, pp 210-227

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Epilogue

-

- Book:

- V. S. Naipaul and World Literature

- Published online:

- 01 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 08 February 2024, pp 198-212

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - “The English Language Was Mine; The Tradition Was Not”

-

- Book:

- V. S. Naipaul and World Literature

- Published online:

- 01 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 08 February 2024, pp 30-57

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Rorty, Irony, and Neoliberalism

- from Part III - Irony’s Impact

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of Irony and Thought

- Published online:

- 20 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 07 December 2023, pp 96-111

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introducing Derrida

-

- Article

- Export citation

2 - Naming God at Sinai The Gift of the Name

-

- Book:

- Naming God

- Published online:

- 30 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 20 July 2023, pp 9-39

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Anthropocene rupture in international relations: Future politics and international life

-

- Journal:

- Review of International Studies / Volume 49 / Issue 4 / October 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 October 2022, pp. 597-614

- Print publication:

- October 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Judgement and Sense in Modern French Philosophy

- Published online:

- 09 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 23 June 2022, pp 1-8

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Derrida and Différance

-

- Book:

- Judgement and Sense in Modern French Philosophy

- Published online:

- 09 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 23 June 2022, pp 148-177

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

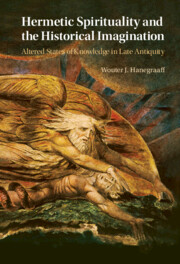

Hermetic Spirituality and the Historical Imagination

- Altered States of Knowledge in Late Antiquity

-

- Published online:

- 16 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 30 June 2022

Judgement and Sense in Modern French Philosophy

- A New Reading of Six Thinkers

-

- Published online:

- 09 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 23 June 2022

Chapter 10 - Pharmakon, Difference and the Arche-Digital

- from Part II - Development

-

-

- Book:

- Globalization and Literary Studies

- Published online:

- 01 April 2022

- Print publication:

- 21 April 2022, pp 159-177

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter One - The Politics of Archival Knowledge in International Courts

-

- Book:

- The Archival Politics of International Courts

- Published online:

- 13 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021, pp 1-29

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Peregrinationes in Psalmos

- from Part II - Religion

-

-

- Book:

- Empire and Religion in the Roman World

- Published online:

- 26 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 19 August 2021, pp 212-231

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Gadamer

- Published online:

- 29 July 2021

- Print publication:

- 12 August 2021, pp 1-14

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

14 - The Constellation of Hermeneutics, Critical Theory, and Deconstruction

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Gadamer

- Published online:

- 29 July 2021

- Print publication:

- 12 August 2021, pp 355-373

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Gadamer (1900–2002)

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Gadamer

- Published online:

- 29 July 2021

- Print publication:

- 12 August 2021, pp 15-43

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Rorty: Reading Continental Philosophy

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Rorty

- Published online:

- 13 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 01 April 2021, pp 261-283

-

- Chapter

- Export citation