133 results

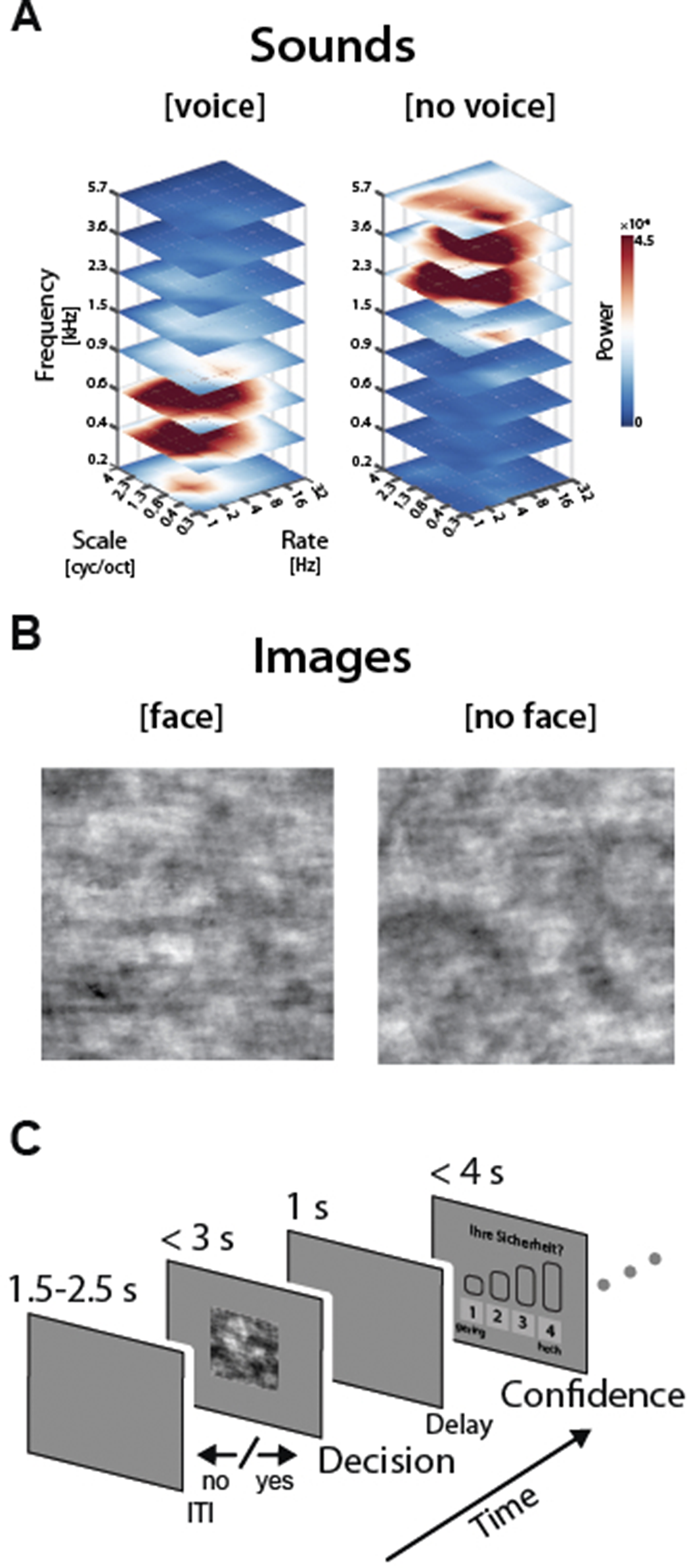

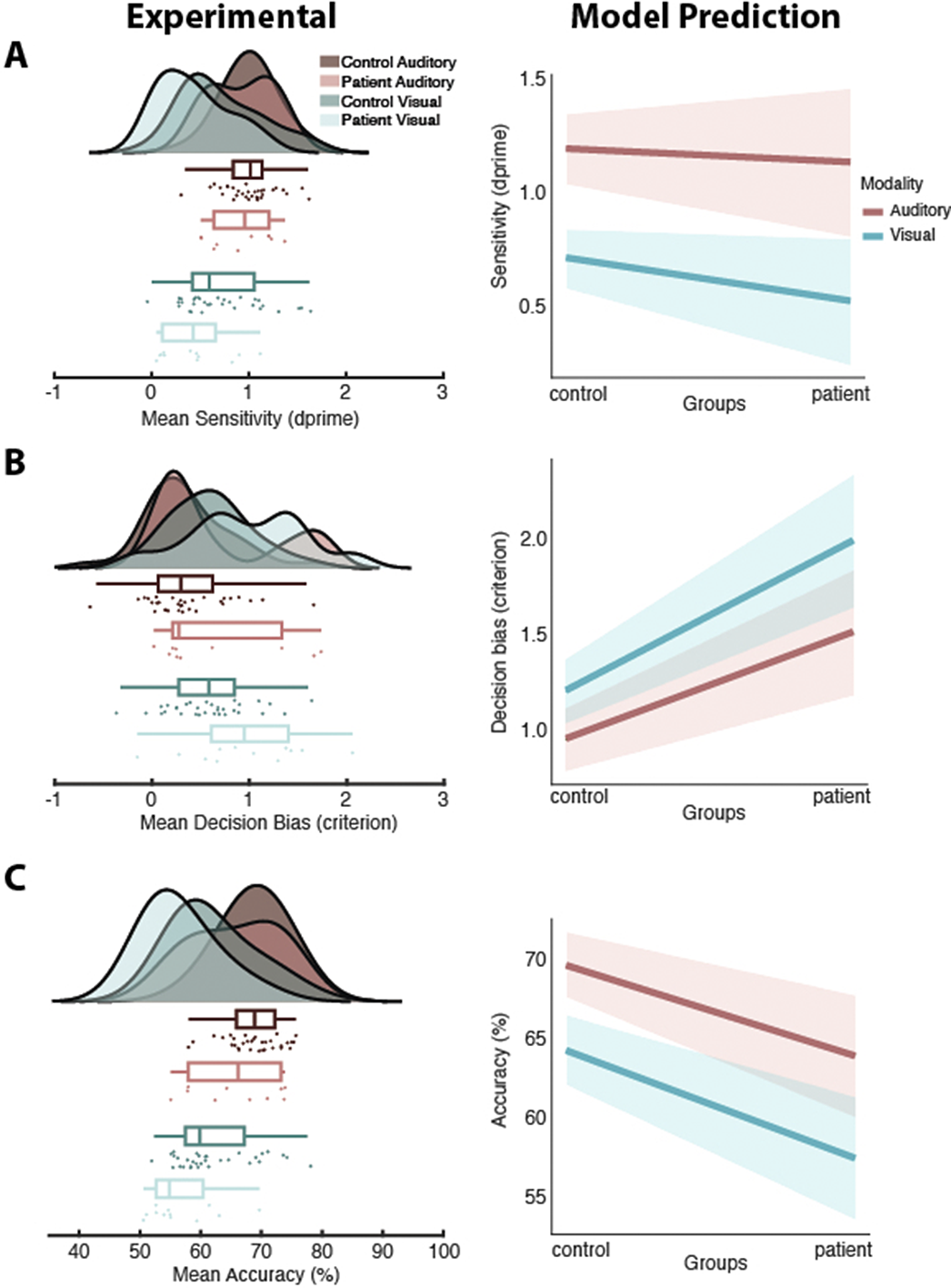

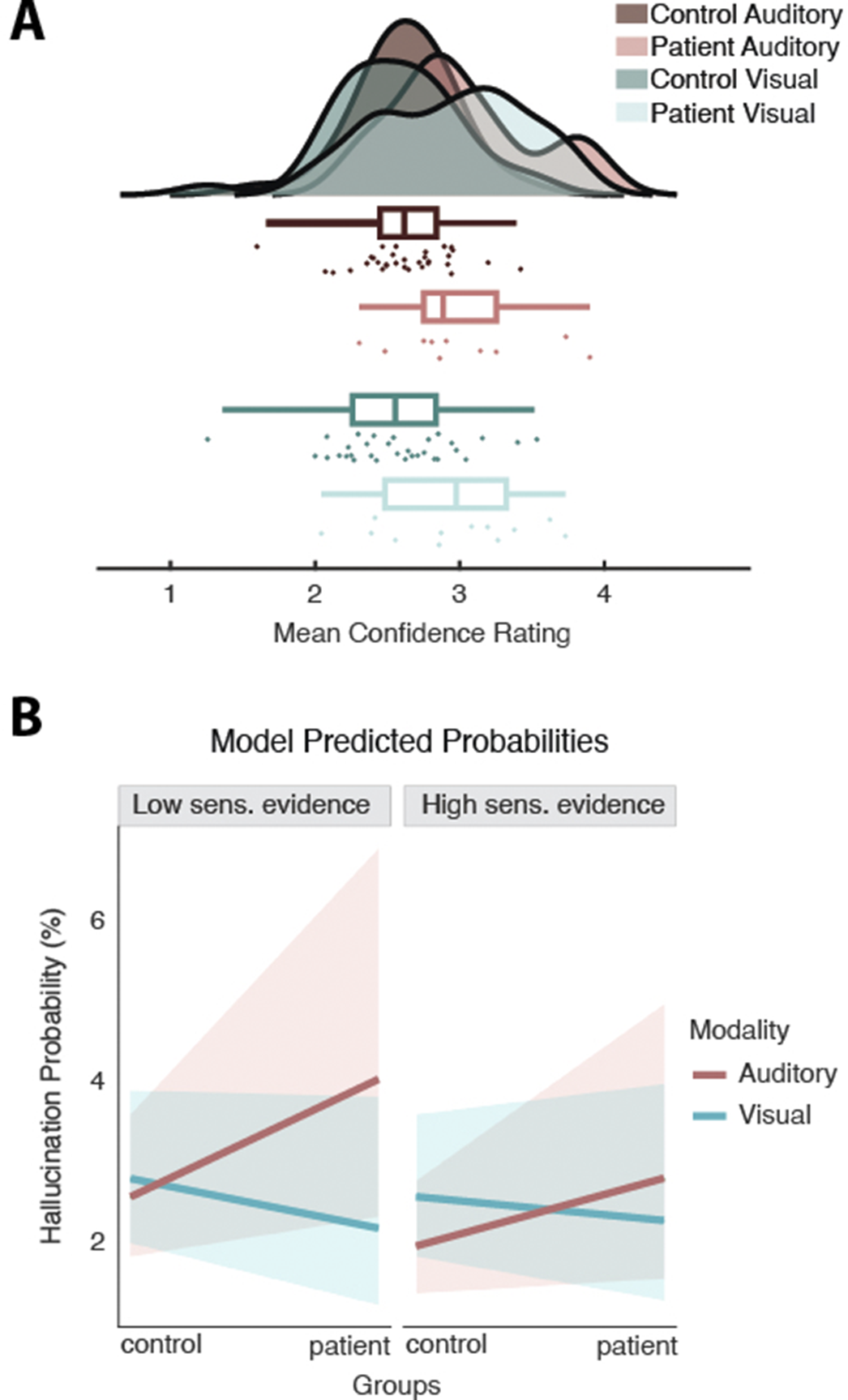

Patients with psychotic disorders exhibit different audio-visual perceptual decision biases and metacognitive abilities

-

- Journal:

- European Psychiatry / Volume 66 / Issue S1 / March 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 July 2023, pp. S129-S130

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Mega-analysis of association between obesity and cortical morphology in bipolar disorders: ENIGMA study in 2832 participants

-

- Journal:

- Psychological Medicine / Volume 53 / Issue 14 / October 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2023, pp. 6743-6753

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Hodge bundle, the universal 0-section, and the log Chow ring of the moduli space of curves

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Compositio Mathematica / Volume 159 / Issue 2 / February 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 February 2023, pp. 306-354

- Print publication:

- February 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Moving from opposition to taking ownership of open science to make discoveries that matter

-

- Journal:

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology / Volume 15 / Issue 4 / December 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 January 2023, pp. 529-532

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Part II - State and Nation Construction

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 143-377

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 390-400

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp v-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp xiii-xxiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - The Space and Time of Albanian History

- from Part I - Between Regional Self-Will and Imperial Rule

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 3-22

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Maps

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A Concise History of Albania

-

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022

5 - Arnavutluk to Albania: The Triumph of Albanianism, 1912–1924

- from Part II - State and Nation Construction

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 145-190

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - The Second World War and the Establishment of the Communist Regime, 1939–1944

- from Part II - State and Nation Construction

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 226-273

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Ottoman Arnavutluk in Crisis, 1800–1912

- from Part I - Between Regional Self-Will and Imperial Rule

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 99-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Between Regional Self-Will and Imperial Rule

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 1-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Interwar Albania: The Rise of Authoritarianism, 1925–1939

- from Part II - State and Nation Construction

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 191-225

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Albanians in the Middle Ages, 500–1500

- from Part I - Between Regional Self-Will and Imperial Rule

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 23-56

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The Albanians under Ottoman Rule: The Classic Period of Arnavutluk, 1500–1800

- from Part I - Between Regional Self-Will and Imperial Rule

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 57-98

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Suggestions for Further Reading (literature in non-Balkan languages)

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of Albania

- Published online:

- 18 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 29 September 2022, pp 382-389

-

- Chapter

- Export citation