Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Why Heisig Matters

- 1 From the Nazi Past to the Cold War Present

- 2 Art for an Educated Nation

- 3 Against the Wall: Murals, Modern Art, and Controversy

- 4 The Contentious Emergence of the “Leipzig School”

- 5 Portraying Workers and Revolutionaries

- Conclusion: The Quintessential German Artist

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Introduction: Why Heisig Matters

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Why Heisig Matters

- 1 From the Nazi Past to the Cold War Present

- 2 Art for an Educated Nation

- 3 Against the Wall: Murals, Modern Art, and Controversy

- 4 The Contentious Emergence of the “Leipzig School”

- 5 Portraying Workers and Revolutionaries

- Conclusion: The Quintessential German Artist

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

They paint more German in the GDR.

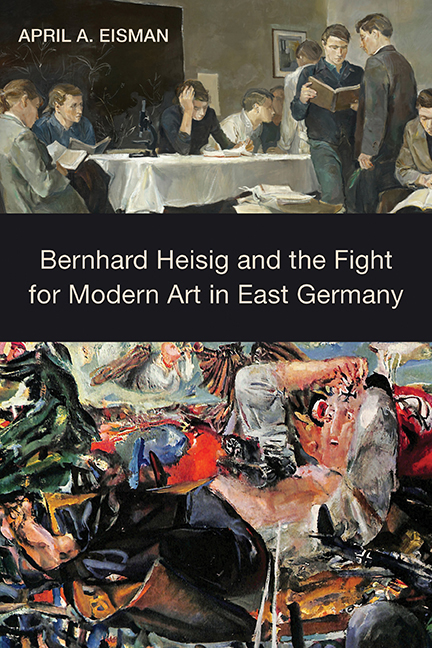

—Günter Grass, 1982In 1997, Bernhard Heisig (1925–2011) was commissioned to create a painting for the Reichstag building in Berlin. One of East Germany's most successful artists, Heisig had seemed a natural choice for inclusion in what is now the Bundestag's permanent art collection, a veritable w ho's who of contemporary German artists, including Joseph Beuys, Anselm Kiefer, and Gerhard Richter. In the 1980s, Heisig had been highly praised on both sides of the Berlin Wall for his artistic commitment to the German tradition and especially to Adolph Menzel, Lovis Corinth, Max Beckmann, and Otto Dix. He regularly exhibited prints and paintings in major international art exhibitions such as documenta and the Venice Biennale as well as in numerous exhibitions in West Germany. He also painted the official portrait of the West German chancellor Helmut Schmidt for the German Chancellery in 1986. Three years later, when the Berlin Wall fell, much of Heisig's work was already in the West in a large retrospective exhibition that had opened to praise at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in West Berlin on September 30. It was the first—and ultimately only—major solo exhibition of a contemporary East German artist to be organized in a joint effort by curators from both Germanys.

But the choice to include a work by Heisig in the Reichstag building just a few years after the Berlin Wall fell was heavily contested in the press. In February 1998, the eastern German art critic Christoph Tannert (b. 1955) published a letter in several newspapers arguing that to give Heisig the commission was “not only an art historical mistake, but also a political lack of instinct.” The problem, he stated, was Heisig's “cooperation with the GDR regime,” which Tannert saw as standing “in crass opposition to a democratic horizon of values.” Fifty-eight cultural and political figures signed the letter, including a number of eastern German artists from the alternative scene.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2018