Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 The Ends of First Sf: Pioneers as Veterans

- 2 After the New Wave: After Science Fiction?

- 3 Beyond Apollo: Space Fictions after the Moon Landing

- 4 Big Dumb Objects: Science Fiction as Self-Parody

- 5 The Rise of Fantasy: Swords and Planets

- 6 Home of the Extraterrestrial Brothers: Race and African American Science Fiction

- 7 Alien Invaders: Vietnam and the Counterculture

- 8 This Septic Isle: Post-Imperial Melancholy

- 9 Foul Contagion Spread: Ecology and Environmentalism

- 10 Female Counter-Literature: Feminism

- 11 Strange Bedfellows: Gay Liberation

- 12 Saving the Family? Children's Fiction

- 13 Eating the Audience: Blockbusters

- 14 Chariots of the Gods: Pseudoscience and Parental Fears

- 15 Towers of Babel: The Architecture of Sf

- 16 Ruptures: Metafiction and Postmodernism

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

4 - Big Dumb Objects: Science Fiction as Self-Parody

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 The Ends of First Sf: Pioneers as Veterans

- 2 After the New Wave: After Science Fiction?

- 3 Beyond Apollo: Space Fictions after the Moon Landing

- 4 Big Dumb Objects: Science Fiction as Self-Parody

- 5 The Rise of Fantasy: Swords and Planets

- 6 Home of the Extraterrestrial Brothers: Race and African American Science Fiction

- 7 Alien Invaders: Vietnam and the Counterculture

- 8 This Septic Isle: Post-Imperial Melancholy

- 9 Foul Contagion Spread: Ecology and Environmentalism

- 10 Female Counter-Literature: Feminism

- 11 Strange Bedfellows: Gay Liberation

- 12 Saving the Family? Children's Fiction

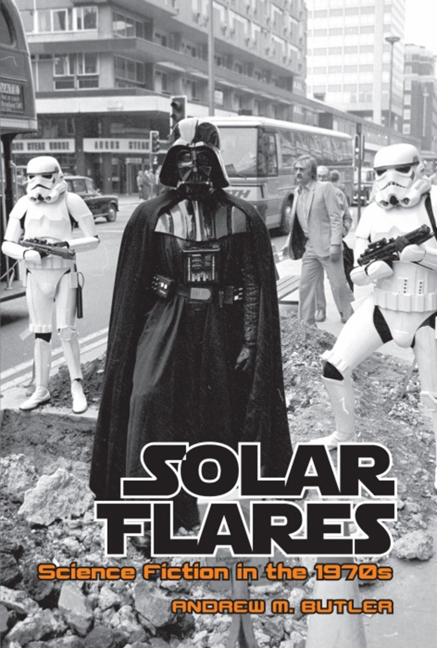

- 13 Eating the Audience: Blockbusters

- 14 Chariots of the Gods: Pseudoscience and Parental Fears

- 15 Towers of Babel: The Architecture of Sf

- 16 Ruptures: Metafiction and Postmodernism

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

At one point the characters in Michael Coney's Charisma (1975) compare their situation to earlier sf: ‘Straight out of H.G. Wells, eh? You ever read Wells, Alan?’ Alan has, and admits, ‘The man had quite an imagination, in his day. […] It was good stuff, once. Reads a bit slow, now’ (1975: 13). In this chapter, I will examine sf that engages with precursors to the Gernsback–Campbell continuum: Mary Shelley (Brian Aldiss and a number of films), H. G. Wells (Aldiss, again, film adaptations and sequels or rewritings by Manley Wade Wellman and Wade Wellman, George H. Smith, K. W. Jeter and Christopher Priest) and Jules Verne (Michael Moorcock). The nineteenth-century writers had been active during the period of European imperialism, with the scramble for Africa and an exploitation of South East Asia and Oceania. European privilege had assumed that the rest of the world offered them exploitable resources and the slave trade redistributed populations with implications to this day. European colonialism was in decline during the 1970s, while American neo-colonialism was in evidence. Some of these writers addressed the political assumptions of imperialism. One means of doing so was through the imagining of a colossal novum, a recurrent trope that has been labelled the Big Dumb Object (Kaveney 1981: 25) – especially in novels by Larry Niven, Arthur C. Clarke, Bob Shaw, Christopher Priest, Frederik Pohl, Philip José Farmer, Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett – whose vast scale ensures that sf teeters on the edge of self-parody. This produces sf that is in part about sf.

Many candidates have been suggested for the first sf narrative, at one extreme classical myths and works by Plato, Homer, Ovid or Lucian of Samosata for a long history of a mode, at the other the pulp magazines of editors such as Gernsback for a generic history. Aldiss's Billion Year Spree (1973) offered a literary account in which sf's ur-text was Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) – ‘the first real science fiction novel’ (Aldiss 1973: 26; cf. 29). Aldiss dramatised his thesis in Frankenstein Unbound (1973), in which an American politician, Joe Bodenland, notes that ‘Frankenstein was regarded by the twenty-first century as the first novel of the Scientific Revolution and, incidentally, as the first novel of science-fiction’ (1982: 47).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Solar FlaresScience Fiction in the 1970s, pp. 51 - 64Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2012