Architectural Invention in Renaissance Rome

Architectural Invention in Renaissance Rome Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Figures

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Note on Translations and Abbreviations

- Introduction: The Nature of Invention, in Word and Image

- 1 Reviving the Corpse

- 2 Writing Architecture

- 3 Sperulo's Vision

- 4 Encomia of the Unbuilt

- 5 Metastructures of Word and Image

- 6 Dynamic Design

- Conclusion: Building With Mortar and Verse

- APPENDIX I Francesco Sperulo, Villa Iulia Medica versibus fabricata/ The Villa Giulia Medicea Constructed in Verse: critical edition and translation by Nicoletta Marcelli and gloss by the Author

- APPENDIX II Francesco Sperulo, Villa Iulia Medica versibus fabricata: Analysis of the presentation manuscript

- APPENDIX III Francesco Sperulo, Ad Leonem X de sua clementia elegia xviiii

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

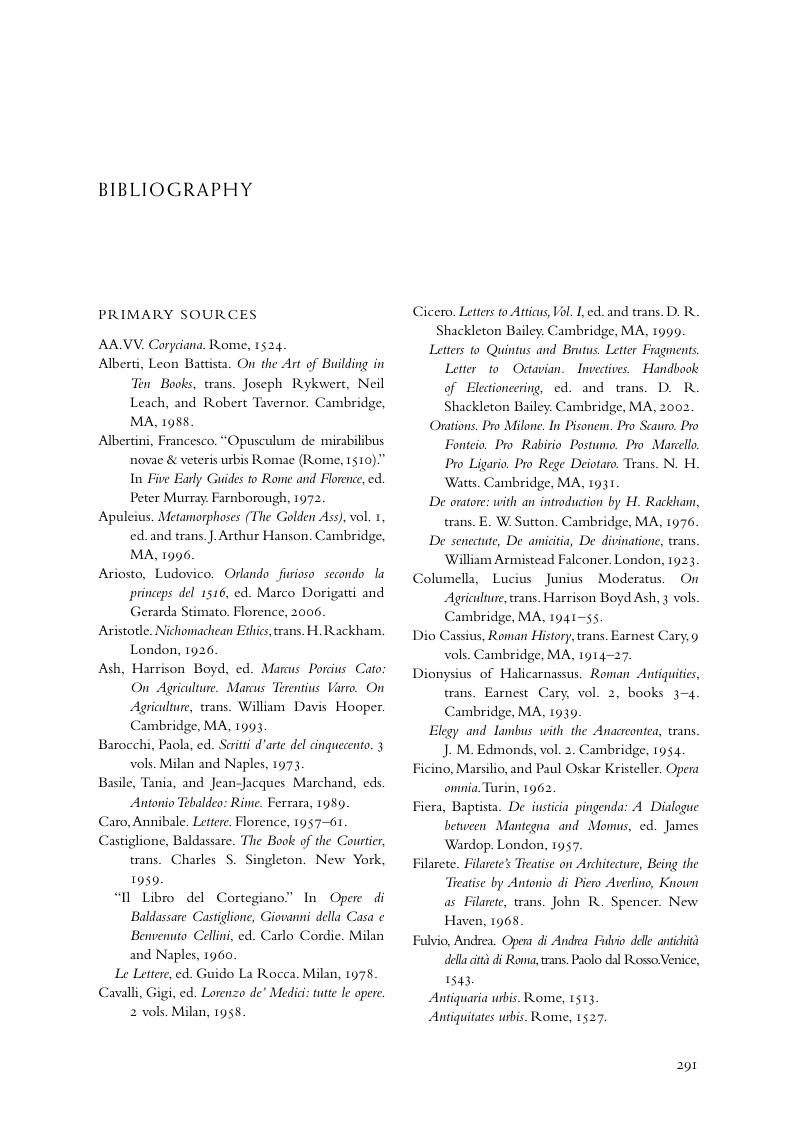

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 January 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Figures

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Note on Translations and Abbreviations

- Introduction: The Nature of Invention, in Word and Image

- 1 Reviving the Corpse

- 2 Writing Architecture

- 3 Sperulo's Vision

- 4 Encomia of the Unbuilt

- 5 Metastructures of Word and Image

- 6 Dynamic Design

- Conclusion: Building With Mortar and Verse

- APPENDIX I Francesco Sperulo, Villa Iulia Medica versibus fabricata/ The Villa Giulia Medicea Constructed in Verse: critical edition and translation by Nicoletta Marcelli and gloss by the Author

- APPENDIX II Francesco Sperulo, Villa Iulia Medica versibus fabricata: Analysis of the presentation manuscript

- APPENDIX III Francesco Sperulo, Ad Leonem X de sua clementia elegia xviiii

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Architectural Invention in Renaissance RomeArtists, Humanists, and the Planning of Raphael's Villa Madama, pp. 291 - 319Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2018