Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Part I Perspectives on the 1927 Solvay conference

- Part II Quantum foundations and the 1927 Solvay conference

- 5 Quantum theory and the measurement problem

- 6 Interference, superposition and wave packet collapse

- 7 Locality and incompleteness

- 8 Time, determinism and the spacetime framework

- 9 Guiding fields in 3-space

- 10 Scattering and measurement in de Broglie's pilot-wave theory

- 11 Pilot-wave theory in retrospect

- 12 Beyond the Bohr–Einstein debate

- Part III The proceedings of the 1927 Solvay conference

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

8 - Time, determinism and the spacetime framework

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 March 2013

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Part I Perspectives on the 1927 Solvay conference

- Part II Quantum foundations and the 1927 Solvay conference

- 5 Quantum theory and the measurement problem

- 6 Interference, superposition and wave packet collapse

- 7 Locality and incompleteness

- 8 Time, determinism and the spacetime framework

- 9 Guiding fields in 3-space

- 10 Scattering and measurement in de Broglie's pilot-wave theory

- 11 Pilot-wave theory in retrospect

- 12 Beyond the Bohr–Einstein debate

- Part III The proceedings of the 1927 Solvay conference

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Time in quantum theory

By 1920, the spectacular confirmation of general relativity, during the solar eclipse of 1919, had made Einstein a household name. Not only did relativity theory (both special and general) upset the long-received Newtonian ideas of space and time, it also stimulated a widespread ‘operationalist’ attitude to physical theories. Physical quantities came to be seen as inextricably interwoven with our means of measuring them, in the sense that any limits on our means of measurement were taken to imply limits on the definability, or ‘meaningfulness’, of the physical quantities themselves. In particular, Einstein's relativity paper of 1905 – with its operational analysis of simultaneity – came to be widely regarded as a model for the new operationalist approach to physics.

Not surprisingly, then, as the puzzles continued to emerge from atomic experiments, in the 1920s a number of workers suggested that the concepts of space and time would require still further revision in the atomic domain. Thus, Campbell (1921, 1926) suggested that the puzzles in atomic physics could be removed if the concept of time was given a purely statistical significance: ‘time, like temperature, is a purely statistical conception, having no meaning except as applied to statistical aggregates’ (quoted in Beller 1999, p. 97).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

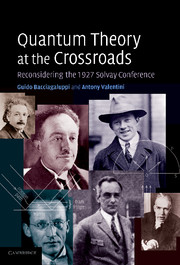

- Quantum Theory at the CrossroadsReconsidering the 1927 Solvay Conference, pp. 184 - 196Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2009