Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Human disasters: humanitarianism and the transnational turn in the wake of World War I

- 1 “Rights, not charity”: René Cassin and war victims

- 2 Justice and peace: Albert Thomas, the International Labor Organization, and the dream of a transnational politics of social rights

- 3 The tragedy of being stateless: Fridtjof Nansen and the rights of refugees

- 4 The hungry and the sick: Herbert Hoover, the Russian famine, and the professionalization of humanitarian aid

- 5 Humanitarianism old and new: Eglantyne Jebb and children's rights

- Conclusion Human dignity: from humanitarian rights to human rights

- Further reading

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Introduction - Human disasters: humanitarianism and the transnational turn in the wake of World War I

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Human disasters: humanitarianism and the transnational turn in the wake of World War I

- 1 “Rights, not charity”: René Cassin and war victims

- 2 Justice and peace: Albert Thomas, the International Labor Organization, and the dream of a transnational politics of social rights

- 3 The tragedy of being stateless: Fridtjof Nansen and the rights of refugees

- 4 The hungry and the sick: Herbert Hoover, the Russian famine, and the professionalization of humanitarian aid

- 5 Humanitarianism old and new: Eglantyne Jebb and children's rights

- Conclusion Human dignity: from humanitarian rights to human rights

- Further reading

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

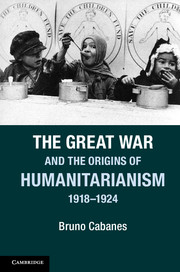

The Great War in Europe was an unprecedented catastrophe. By mid August 1914, the devastated cities of Dinant and Louvain had already come to symbolize the horror of industrialized warfare. The first reports of the German Army's atrocities in Belgium and France, of massacres, rapes, deportations, and the destruction of hospitals and historic monuments, soon followed. These reports were only confirmed by the brutal military occupations on the western front, in the Balkans, in Central and later in Eastern Europe. From the standpoint of humanitarian law, then, in its infancy, the Great War was nothing but a series of bloody affronts to human dignity. The year 1915 marked a turning point, with its increased violence against civilian populations and the beginning of the Armenian genocide. Even the Armistice brought no relief. In Europe and in the Near East, refugees fled revolutions, civil wars, and persecution. Hundreds of thousands of families suffered famine and epidemics. Meanwhile, millions of wounded and disabled soldiers struggled to return to their civilian lives. And yet in the end, the Great War did more than create disaster. It fostered deep and long-term pacifist feeling among a substantial population, and it made the protection of all the war's victims, civilians and soldiers alike, an absolute necessity—a project that drew to it a surprisingly large and talented group of activists and their supporters.

The timid steps taken in this direction during the peace negotiations were short-lived. In June 1919, Germany acknowledged the Allies’ right to prosecute, before military tribunals, those accused of committing “acts in violation of the laws and customs of war.” But the Reichsgericht or Supreme Court established in Leipzig in 1921 was a mockery of justice: of the initial list of more than 800 accused “war criminals,” including the German generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff, the tribunal in fact prosecuted only 45—all of whom were mid-level German Army officers.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014