Book contents

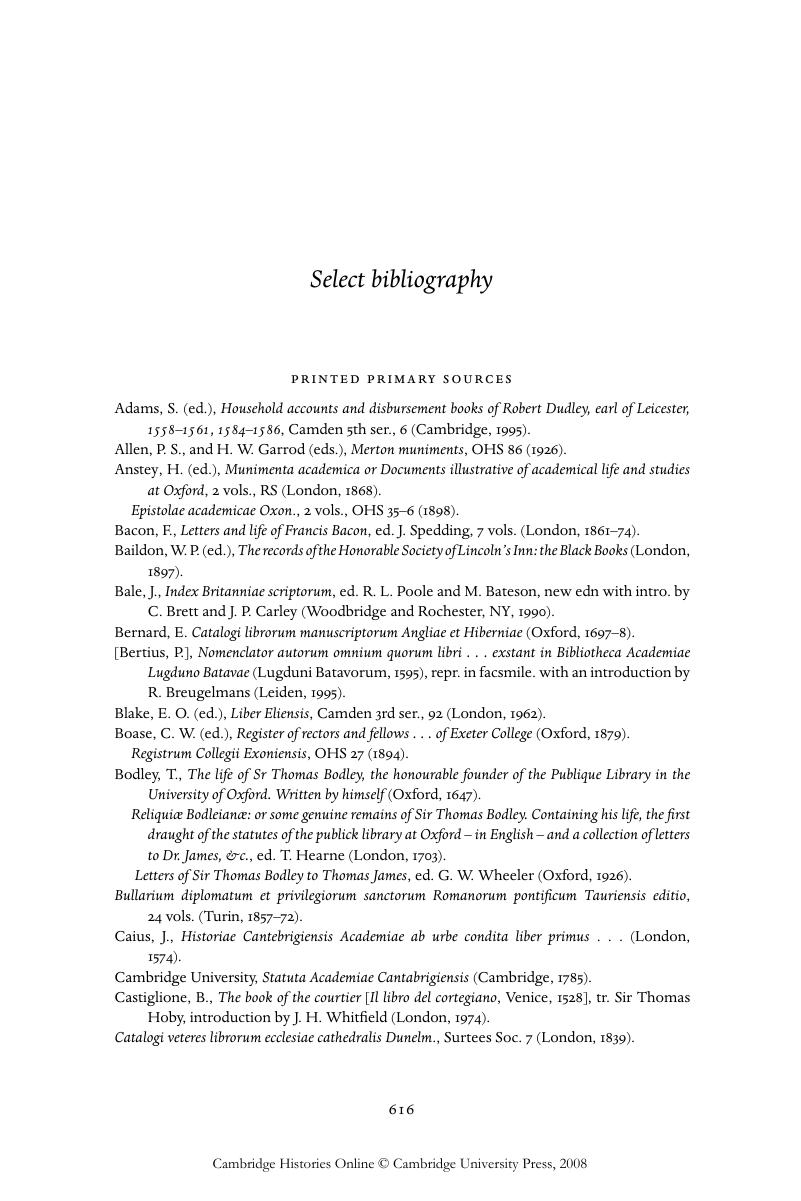

Select bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2008

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge History of Libraries in Britain and Ireland , pp. 616 - 640Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2006