Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of tables

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Libanius at the margins

- Part I Reading Libanius

- Part II Libanius’ texts: rhetoric, self-presentation and reception

- Part III Contexts: identity, society, tradition

- Appendices: survey of Libanius’ works and of available translations

- References

- Index locorum

- General index

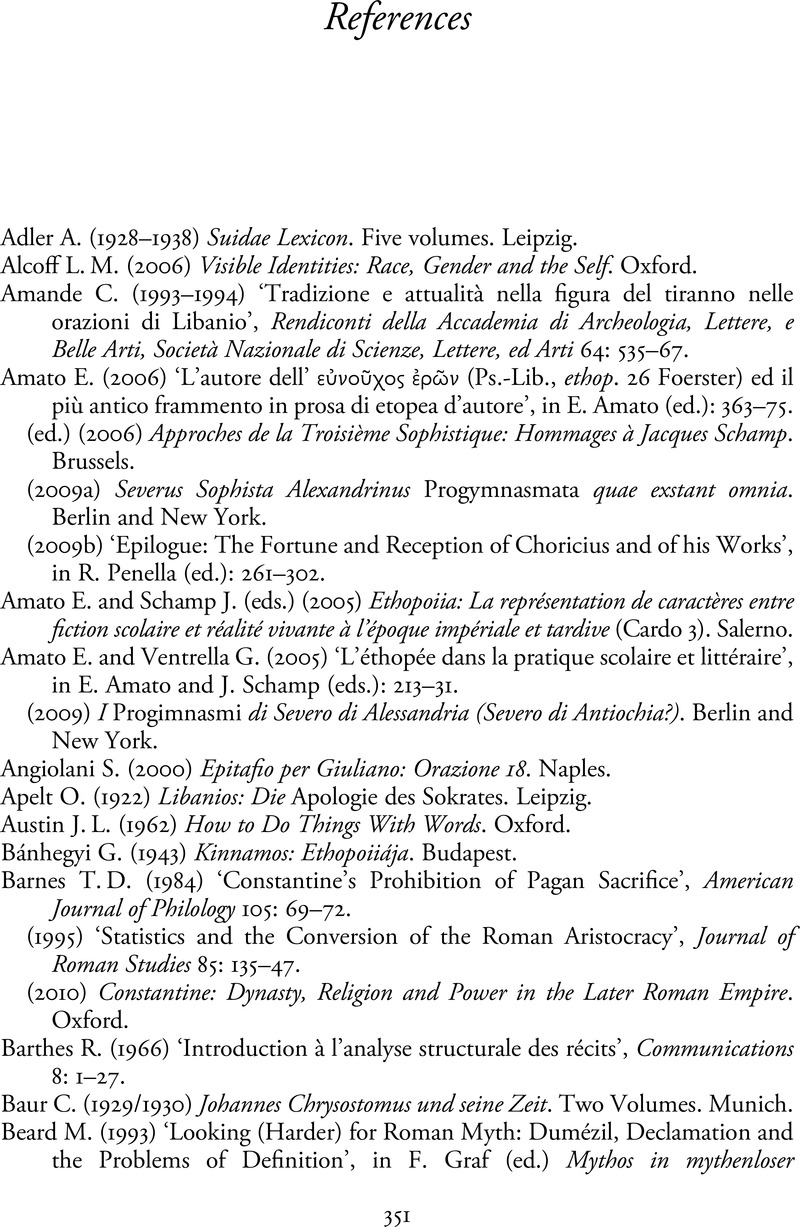

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2014

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of tables

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Libanius at the margins

- Part I Reading Libanius

- Part II Libanius’ texts: rhetoric, self-presentation and reception

- Part III Contexts: identity, society, tradition

- Appendices: survey of Libanius’ works and of available translations

- References

- Index locorum

- General index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- LibaniusA Critical Introduction, pp. 351 - 377Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014