Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: mapping the territory

- 1 Margaret Hoby: the stewardship of time

- 2 The construction of a life: the diaries of Anne Clifford

- 3 Pygmalion's image: the lives of Lucy Hutchinson

- 4 Ann Fanshawe: private historian

- 5 Romance and respectability: the autobiography of Anne Halkett

- 6 Margaret Cavendish: shy person to Blazing Empress

- Conclusion: “The Life of Me”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

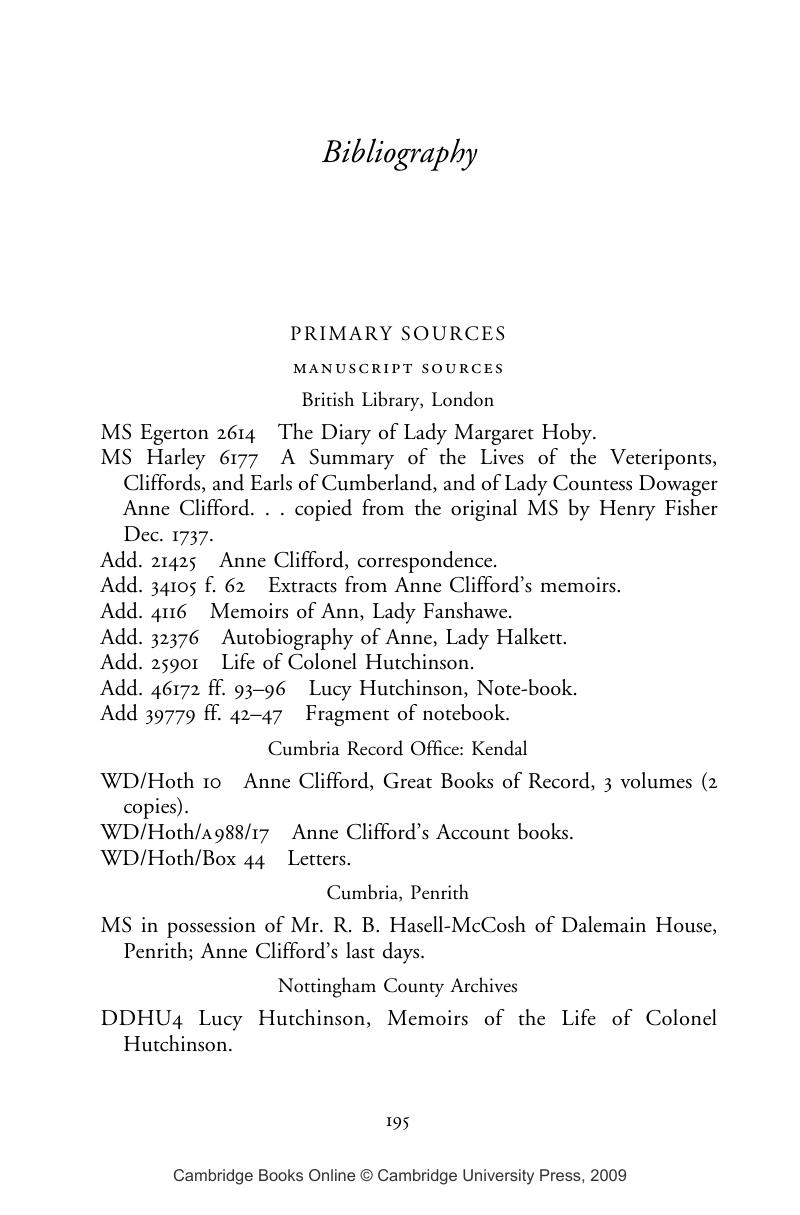

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 September 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: mapping the territory

- 1 Margaret Hoby: the stewardship of time

- 2 The construction of a life: the diaries of Anne Clifford

- 3 Pygmalion's image: the lives of Lucy Hutchinson

- 4 Ann Fanshawe: private historian

- 5 Romance and respectability: the autobiography of Anne Halkett

- 6 Margaret Cavendish: shy person to Blazing Empress

- Conclusion: “The Life of Me”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Autobiography and Gender in Early Modern LiteratureReading Women's Lives, 1600–1680, pp. 195 - 210Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2006