Christianization and Communication in Late Antiquity

Christianization and Communication in Late Antiquity Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Philosophical preaching in the Roman world

- Chapter 2 Rhetoric and society: Contexts of public speaking in late antique Antioch

- Chapter 3 John Chrysostom's congregation in Antioch

- Chapter 4 Teaching to the converted: John Chrysostom's pedagogy

- Chapter 5 Practical knowledge and religious life

- Chapter 6 Habits and the Christianization of daily life

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

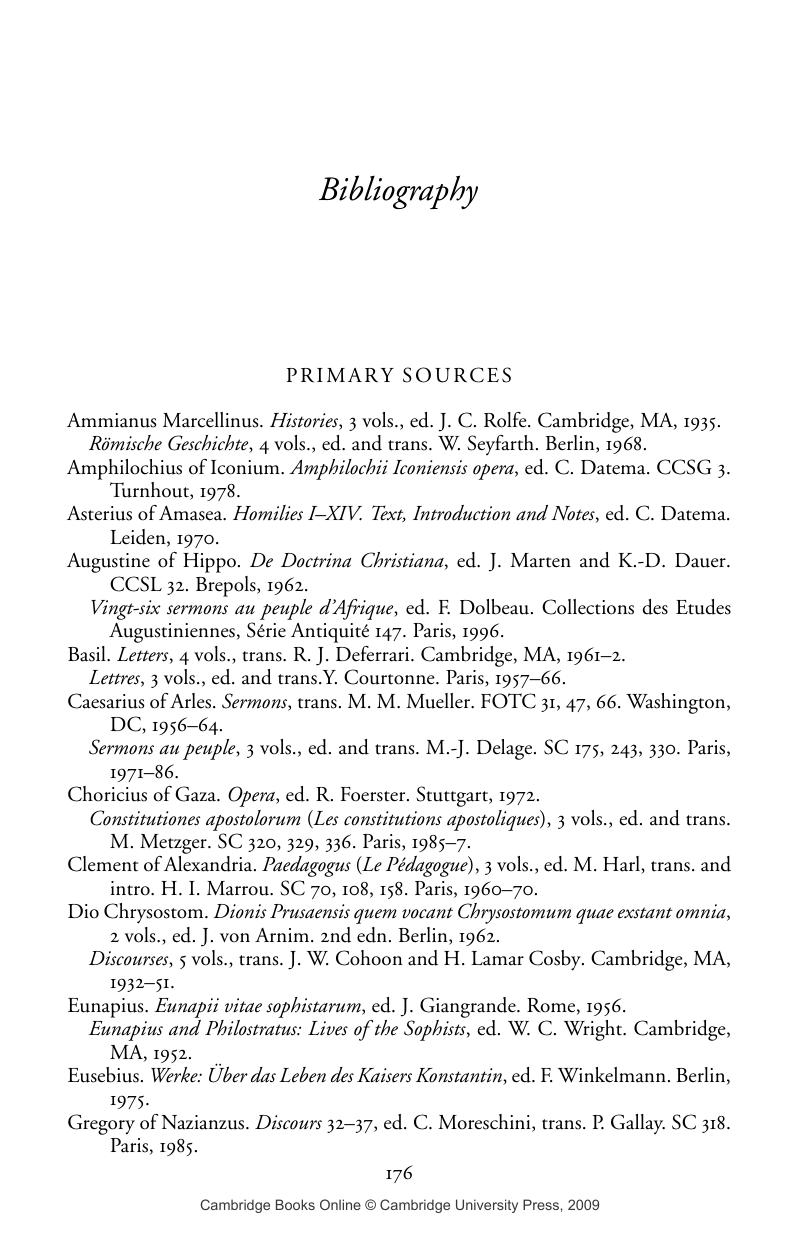

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 September 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Philosophical preaching in the Roman world

- Chapter 2 Rhetoric and society: Contexts of public speaking in late antique Antioch

- Chapter 3 John Chrysostom's congregation in Antioch

- Chapter 4 Teaching to the converted: John Chrysostom's pedagogy

- Chapter 5 Practical knowledge and religious life

- Chapter 6 Habits and the Christianization of daily life

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Christianization and Communication in Late AntiquityJohn Chrysostom and his Congregation in Antioch, pp. 176 - 193Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2006